Climbing-Specific Body Tension

The crux move is steep, you’re toeing in on a small foot chip, and holding your breath as you go for the next hold. You stick the pinch move and use every ounce of effort to maintain body tension on the wall but gravity wins. Rest, re-assess, and try again.

Everyone has experienced failure to generate body tension. Often times it leads to chalk kicking up from landing on the crash pad or maybe your climbing partner questioning why you keep swinging off the wall when you go for the same “reachy” move without success. If body tension is the limiting factor then how do you train it? The simple answer is climbing, but sometimes gyms are closed, seasons prevent you from hopping onto your project, or you just need that extra 10% of “Sharma” strength to keep you on the wall.

Body tension from a functional perspective can be described as a balance of generated internal forces from several muscle groups working in unison to meet or exceed external resistance (like gravity).1-4 Climbing-specific body tension is both an outcome of functional skill and strength.5-6 Skill comes from quality time spent on the wall where body awareness and tension are fine-tuned in specific, functional patterns.5-6 Functional strength is developed when a series of muscles are fired in concert and generates force specific to the functional task. Understanding the areas of limitation in developing body tension in functional positions can prove valuable for both strength improvement and injury reduction for climbers. 1-6

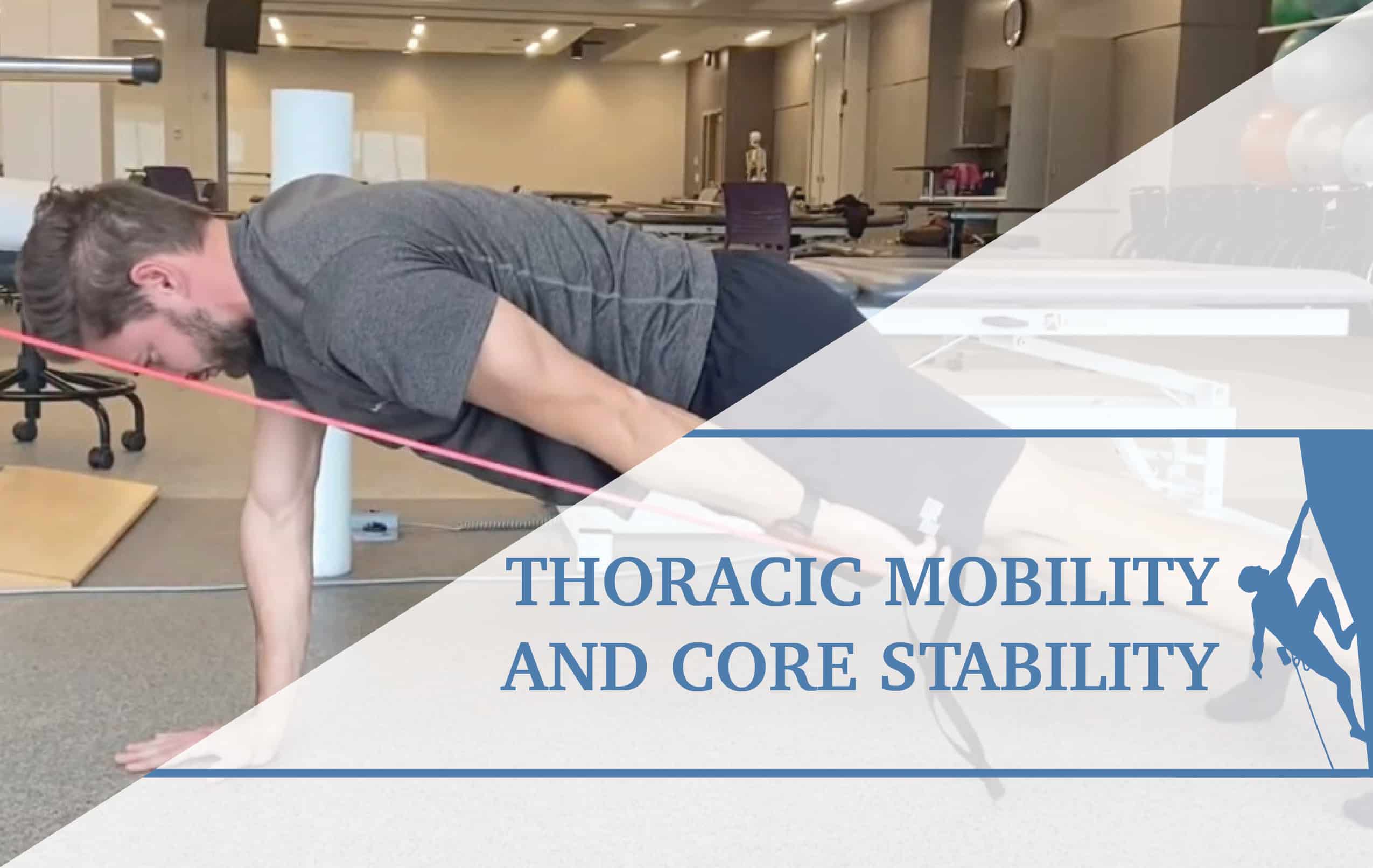

Core strength and stability is often associated with body tension and climbing.6,7 The core is designed to absorb, resist, and overcome forces from various planes of motion and distribute those forces to optimize body position for specific tasks.6-9 However, exercising the core in isolation may neglect training deep trunk musculature and other muscle groups used to generate movement and tension on the wall.6-10 For example, body tension is key to keeping your feet on the wall on a steep route.7-9 The neuromuscular ability to “try hard” and recruit tension in your hamstring, hips, low back, and shoulders can be just as important as the engagement in your core. A multi-modal approach to sport-specific strength training has the potentially to more valuable than isolated core exercises when it comes to developing climbing-specific body tension as well as injury reduction.7,8,10,11

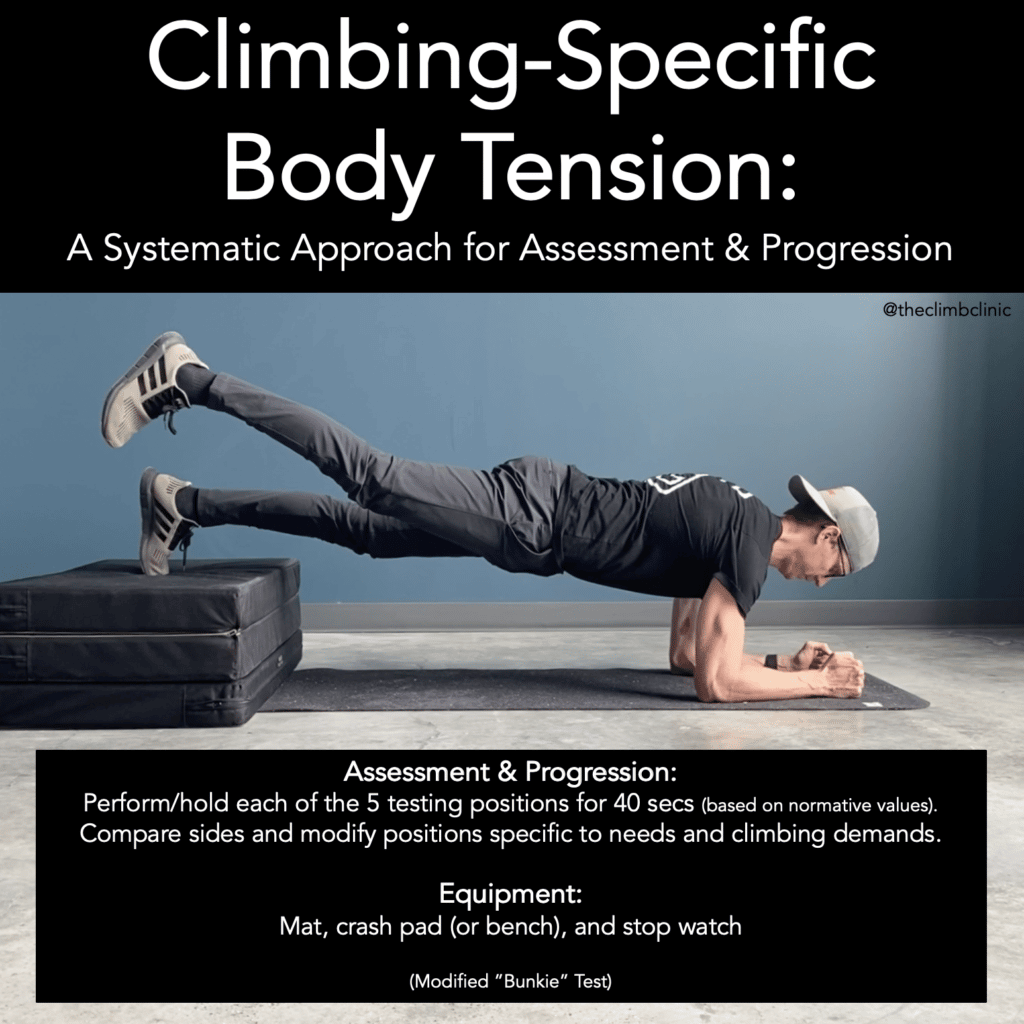

Below is a functional strength and performance test (Modified “Bunkie” Test) that examines the strength capacity of the core, deep trunk musculature, and other critical muscle groups of the upper and lower body used to develop body tension.1-4 The assessment consists of 5 specific testing positions that challenge aspects of body tension associated with climbing (minimal equipment required).1-4 The systematic approach is designed to as an assessment and exercises to highlight areas of strength as well as identify areas asymmetries, weaknesses, or limitations that may benefit from strength training modifications that can be associated with improved body tension while climbing as well as sport-related injury reduction.1-4,10-13

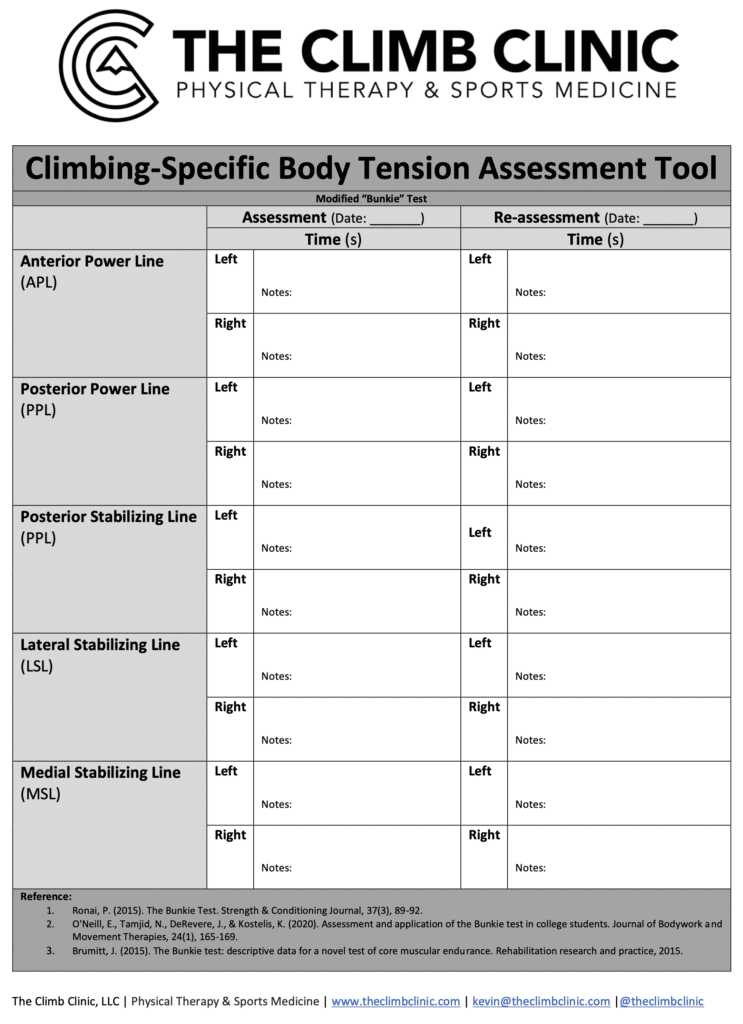

Purpose: Systematic approach to assess asymmetries, muscular strength capacity, and functional performance of an individual under various test positions requiring body tension (core/trunk, upper body, and lower body)

Equipment: Mat, crash pad or bench (25-30 cm), and stop watch

Assessment Duration: 10-20 mins

Goal: Ability to maintain starting test position for 30-40 secs (based off normative values)

Instructions:

Start with both feet initially placed on the bench with the upper body supported by forearms and palms. Once positioned, raise one leg off the bench and the timer is started. The goal is to hold the testing position for a period of time. Normative data for young, healthy adults is to maintain each test position for 30-40 sec. The time stops when you no longer can hold the test position or reached goal time. Rest (30-120 secs) should be implemented before moving forward to the next test. The test should be performed bilaterally to assess strength asymmetries and allow comparison. Record time and additional notes based off test findings (Example: 42 secs, hips felt more fatigued than core). Use testing positions for training purposes and/or use as a means to assess training while climbing.

Testing Positions: 5 test positions performed on each leg/side (10 total positions – see photos)

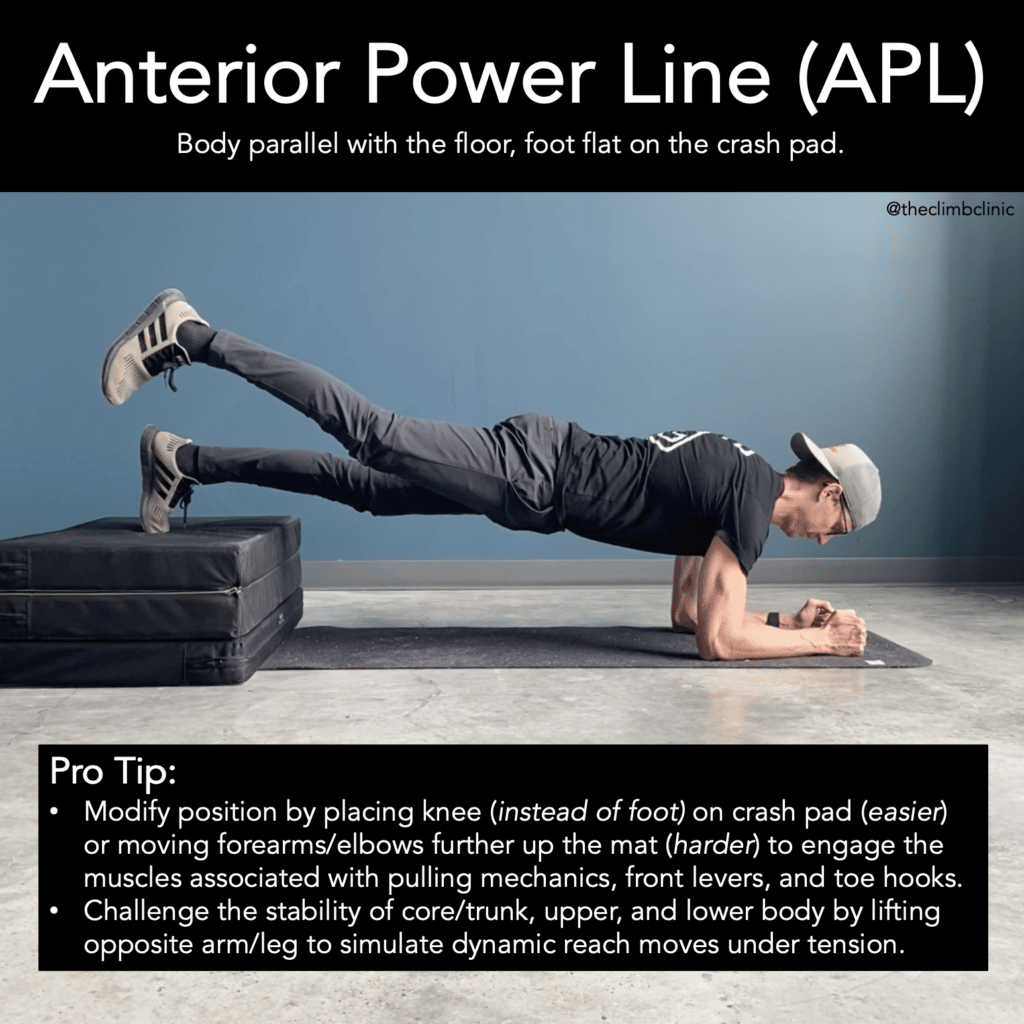

- Anterior Power Line (APL)

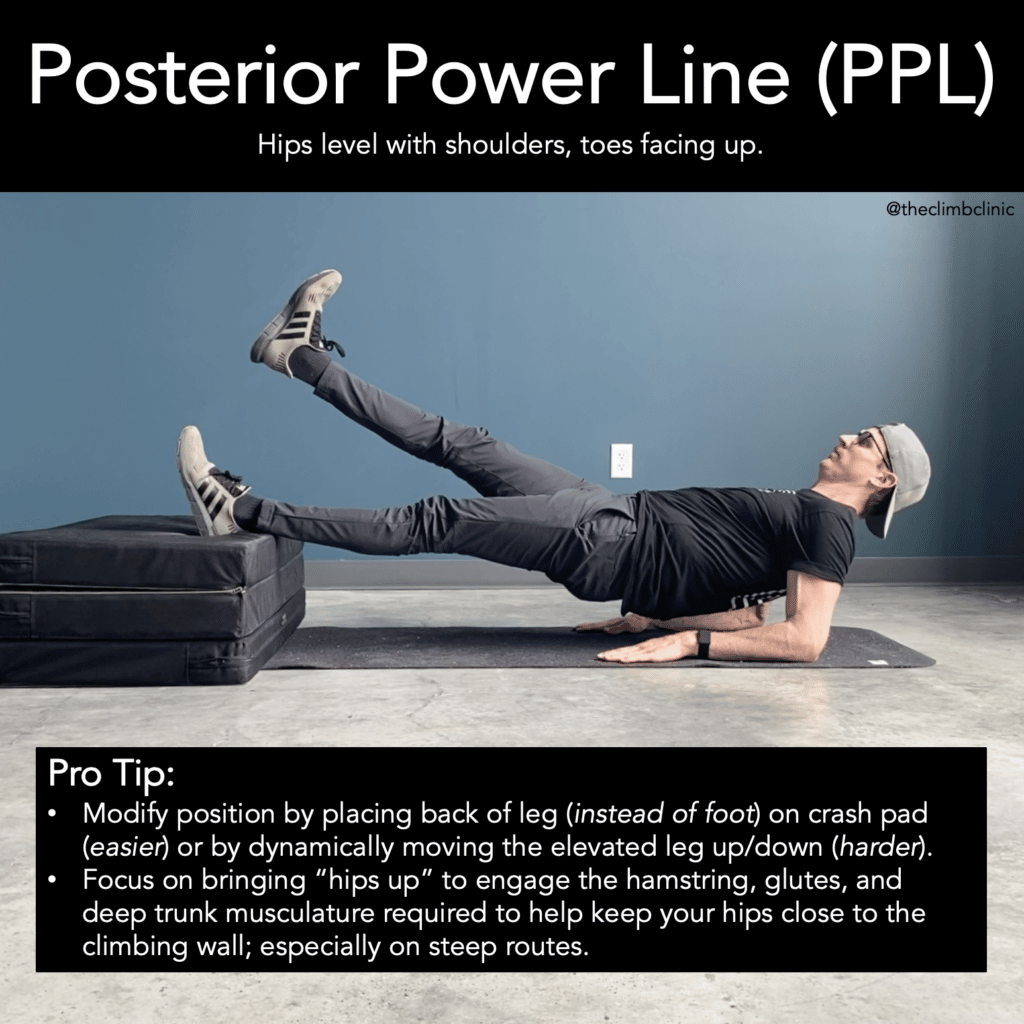

- Posterior Power Line (PPL)

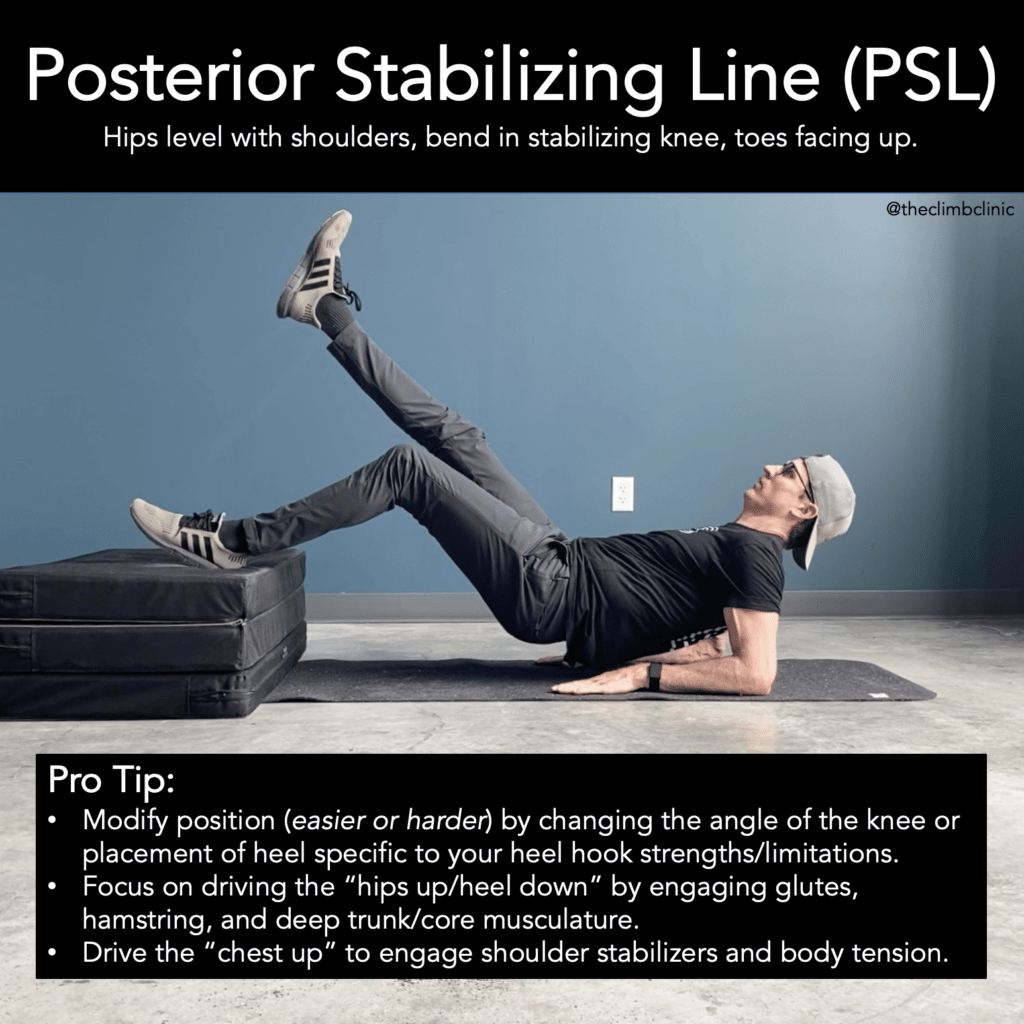

- Posterior Stabilizing Line (PSL)

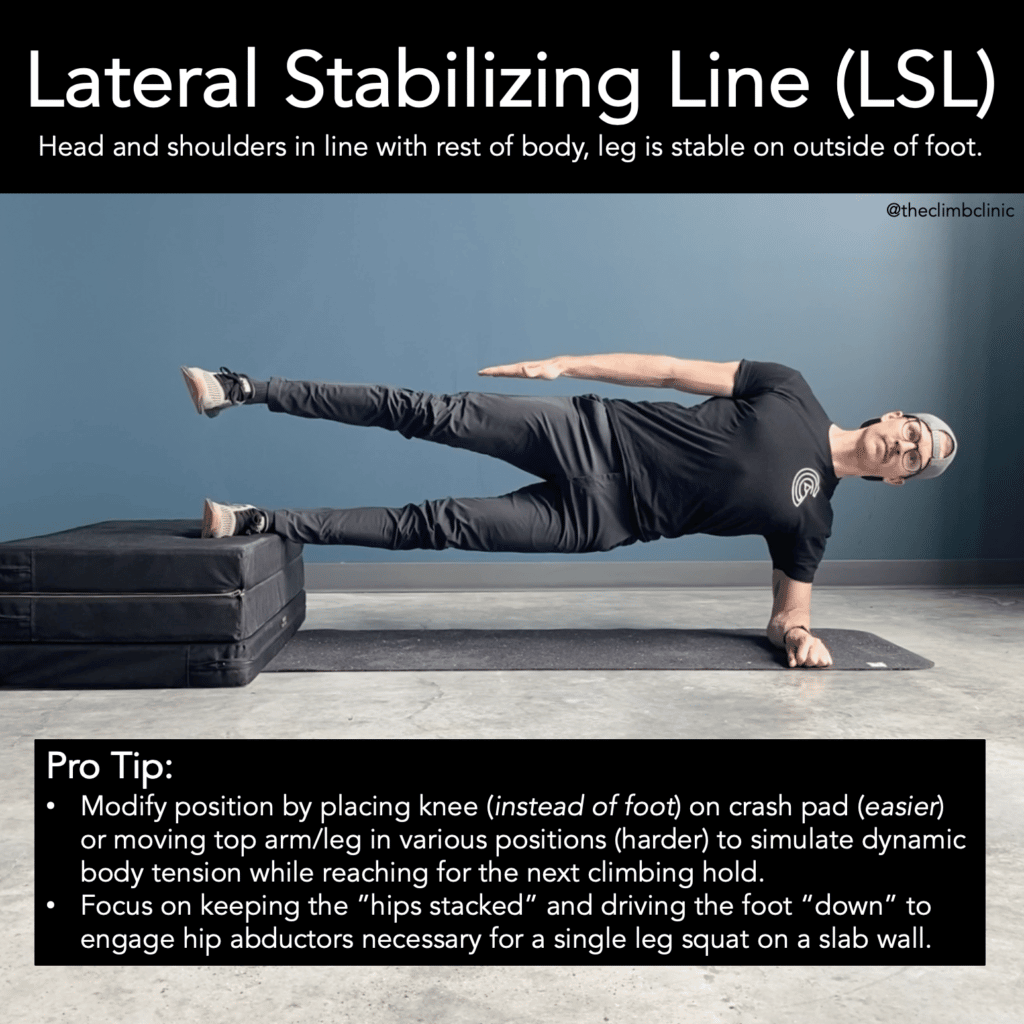

- Lateral Stabilizing Line (LSL)

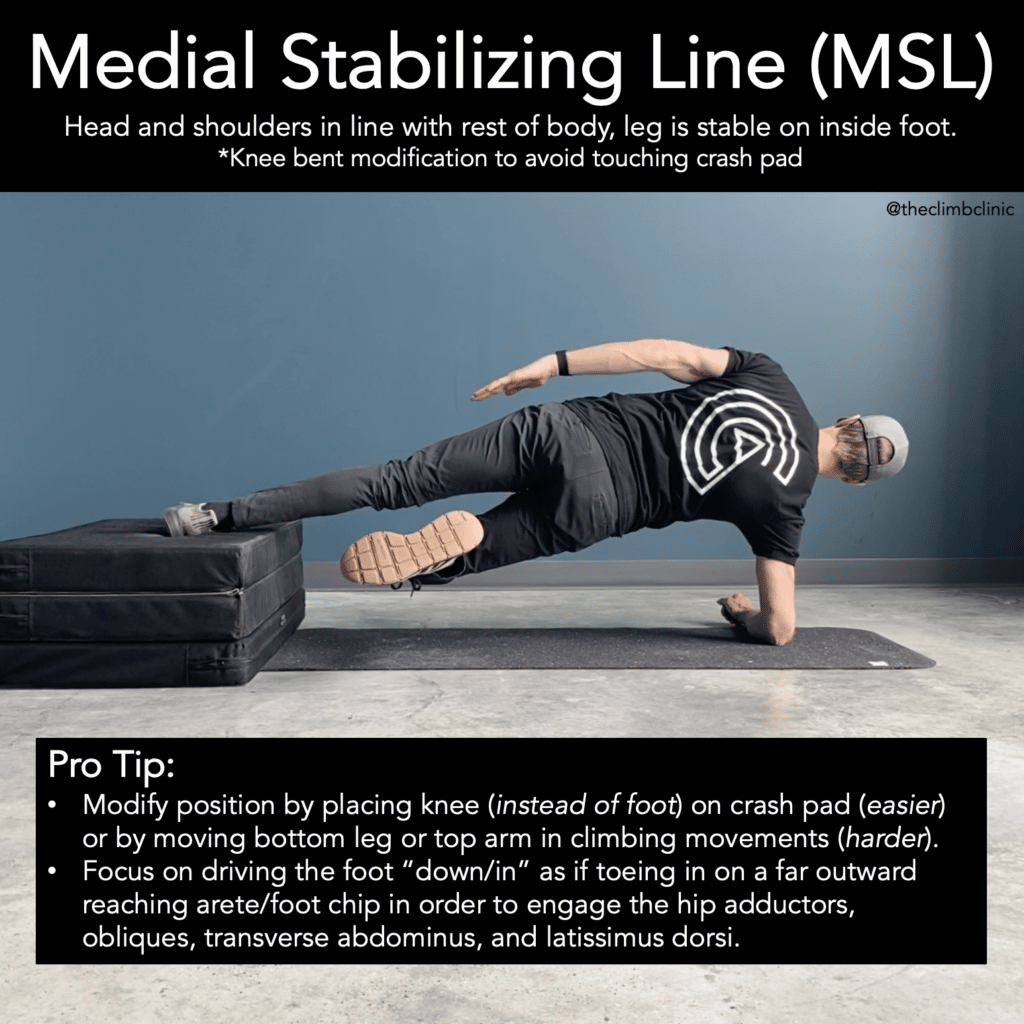

- Medial Stabilizing Line (MSL)

Anterior Power Line

Posterior Power Line

Posterior Stabilizing Line

Lateral Stabilizing Line

Medial Stabilizing Line

About The Author

Kevin is a physical therapist, clinical instructor, and rock climber based out of Boulder, CO. Kevin owns and operates The Climb Clinic (located at G1 Climbing + Fitness) where he specializes in neuromusculoskeletal performance rehab for climbers and mountain athletes. He found his passion for climbing in Colorado while attending Regis University for his Doctorate of Physical Therapy. Kevin is a Board-Certified Orthopaedic Clinical Specialist and recently completed extensive training where he awaits to become a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapy (FAAOMPT) – Expected June 2020. He has had the opportunity to assist at courses teaching clinicians dry needling and spinal manipulative techniques as well as serve as a healthcare provider at the Boulder World Cup in Vail. Kevin takes any chance he gets to climb outside and adventure in Colorado with his wife, Maddie, and pup, Kota.

Email: kevin@theclimbclinic.com

Webpage: theclimbclinic.com

Instagram: @theclimbclinic

Facebook: @theclimbclinic

The Research

- Ronai, P. (2015). The bunkie test. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 37(3), 89-92.

- O’Neill, E., Tamjid, N., DeRevere, J., & Kostelis, K. (2020). Assessment and application of the Bunkie test in college students. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 24(1), 165-169.

- Brumitt, J. (2015). The Bunkie test: descriptive data for a novel test of core muscular endurance. Rehabilitation research and practice, 2015.

- de Witt, B., & Venter, R. (2009). The ‘Bunkie’test: assessing functional strength to restore function through fascia manipulation. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 13(1), 81-88.

- Giles, L. V., Rhodes, E. C., & Taunton, J. E. (2006). The physiology of rock climbing. Sports Medicine, 36(6), 529-545.

- Young, W. B. (2006). Transfer of strength and power training to sports performance. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 1(2), 74-83.

- Wang, X. Q., Zheng, J. J., Yu, Z. W., Bi, X., Lou, S. J., Liu, J., … & Shen, H. M. (2012). A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. PloS one, 7(12).

- Wirth, K., Hartmann, H., Mickel, C., Szilvas, E., Keiner, M., & Sander, A. (2017). Core stability in athletes: a critical analysis of current guidelines. Sports medicine, 47(3), 401-414.

- Bassett, S. H., & Leach, L. L. (2011). The effect of an eight-week training programme on core stability in junior female elite gymnasts, African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 17: supp1 (Supplement) pp. 9-19:: erratum. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 17(3), 567.

- Woollings, K. Y., McKay, C. D., Kang, J., Meeuwisse, W. H., & Emery, C. A. (2015). Incidence, mechanism and risk factors for injury in youth rock climbers. Br J Sports Med, 49(1), 44-50.

- Lauersen, J. B., Andersen, T. E., & Andersen, L. B. (2018). Strength training as superior, dose-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine, 52(24), 1557-1563.

- Van Pletzen, D. (2010). The relationship between the bunkie-test and selected biomotor abilities in elite-level rugby players(Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch).

- Ambegaonkar, J. P., Mettinger, L. M., Caswell, S. V., Burtt, A., & Cortes, N. (2014). Relationships between core endurance, hip strength, and balance in collegiate female athletes. International journal of sports physical therapy, 9(5), 604.

Download the Tool

Click below for a nine page PDF version of the tool that you can download and use.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

Thanks for this. Great tool and test. Do you have any links you could share with specific exercises to improve on areas of weakness.

Example. I did well in all except the Posterior power and stabilizing line tests. What could I do to improved that?

The failed test becomes the exercise! The first step is train yourself with the test. Then you can build into more climbing specific exercises. Best of luck!

Hi Kevin,

Thank you for sharing your test.

I have tried all the positions, but I am having a hard time maintaining the arms position in both the PSL and PPL positions.

My question is: Why the arms have to be in this position?

Thank you

You can adjust your position if you like. Technically, the test position does work the triceps to stabilize (which is a posterior stabilizer) but it also stresses the front of the shoulder (the anterior capsule). So feel free to modify as you see fit!