Managing your mindset and mental health when injured

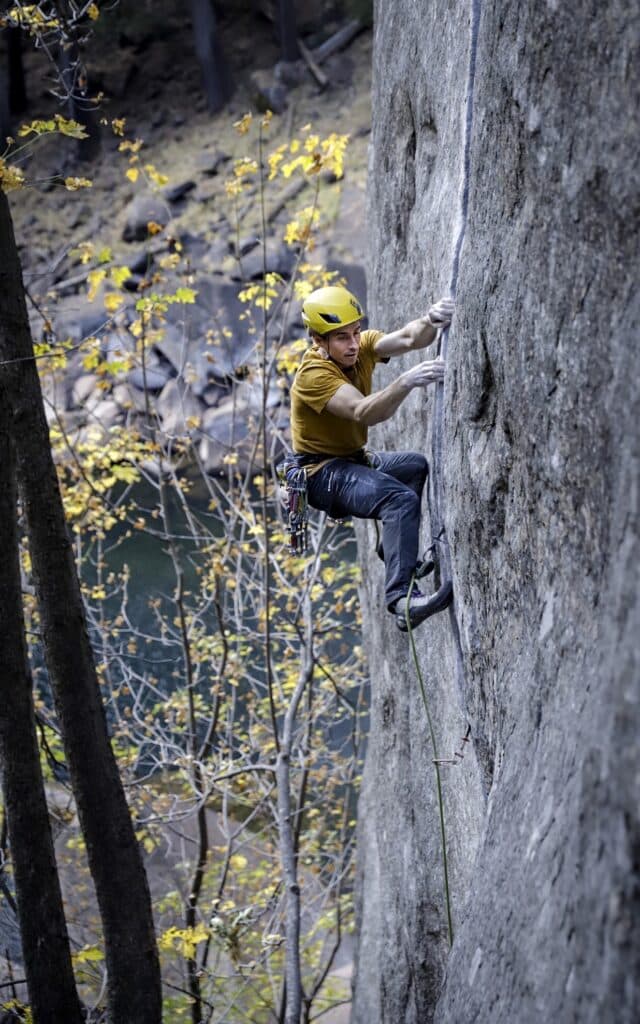

Angus Kille finishing El Corazòn on El Capitan

Tell a non-climbing friend that you’ve got a sore finger and they might not be too sympathetic. For us as climbers, on the other hand, such an injury can feel disastrous. And that makes absolute sense.

OK, maybe it’s a tiny tendon in your finger, or maybe you can still use your bad shoulder for everyday things, but anyone who can’t do their favourite thing anymore is going to find that challenging. What’s more, being a climber is probably part of your identity, and it’s probably where you find friends and support too. For many of us, doing our favourite thing is also a form of self-care, which compounds the challenge of injury.

I write this article from experience as someone who has had more injuries than I can remember over my 28 years as a climber, including a labrum tear that almost ended my career. I’m also a mental training coach that runs a business to help climbers train their minds, so this is a really important area for me.

So what do we do with our minds while our bodies are on the mend? Injury can expose weak points in our mindset and give us the time and space to reconsider our psychological approach to climbing. Often, a mindset shift can play a key role in our recovery, our continued climbing and even preventing further injury.

Here are some key mindset shifts to consider in respect to injury in climbing.

Acceptance can foster an empowering mindset for injury

We have to accept where we are now in order to move forward. This isn’t easy, but if we don’t have acceptance around our injury then we will always be spending energy on what could have been, or what we should have done. We also need to recognise that making comparisons with other climbers or our non-injured self isn’t helping us.

Part of acceptance is also accepting our role in this injury. Sometimes we can get into habits of blaming ourselves and ruminating over what we did wrong. We might also spend time blaming externalities and feeling hard done by, or perhaps flitting between different things to blame. This is a powerless position to be in. The chances are we have some responsibility in this injury, and a little self-kindness here can go a long way. We can remind ourselves that we didn’t set out to get injured, we were motivated to have fun, reach our goals, try hard, perform etc.

It may feel like we have no control of our situation, especially when we feel we are the victim of events. Although we can’t take responsibility for external factors, we can take responsibility for how we respond to this injury. It might be helpful to remember that there are probably times we went climbing and avoided injury, even when it was quite likely.

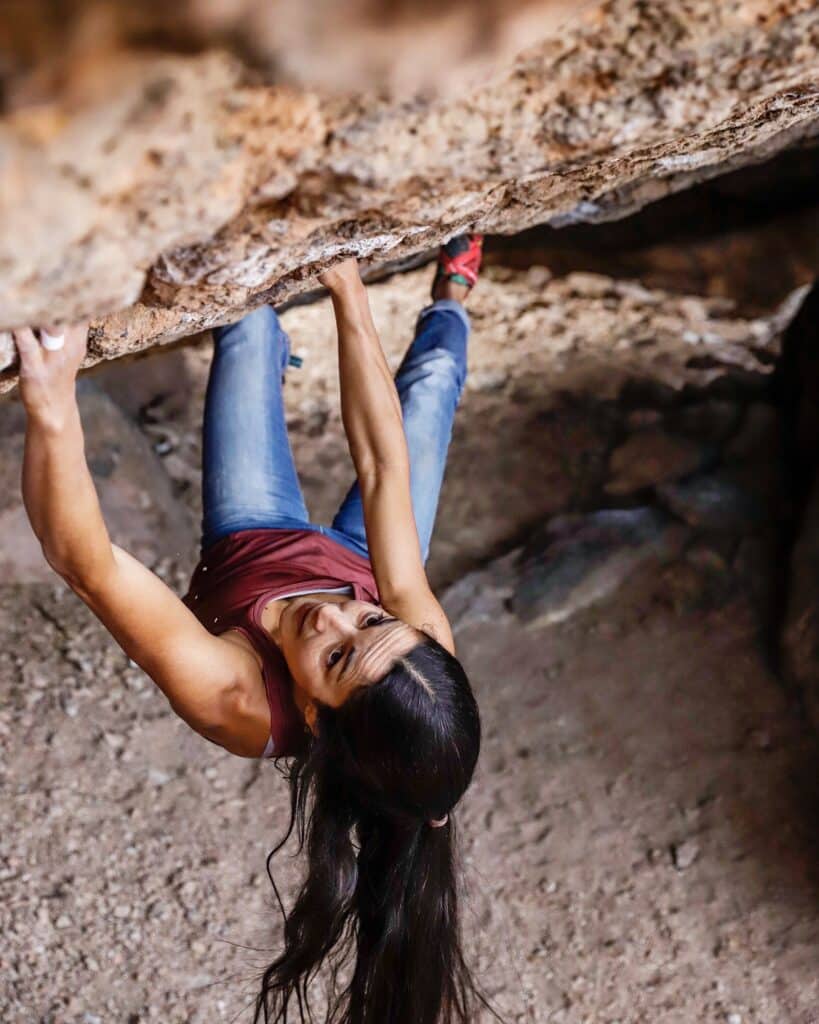

Daila Ojeda bouldering in Bishop

A positive mindset for injury

The chances are that climbing isn’t the only worthwhile thing in your life (bear with me here). If you had unlimited time in your day, I’m sure there are other things you would do with your time other than climbing. Are there some books you always thought you’d read? Or did you want to learn a language? Or spend time with a friend, play an instrument or make art? Maybe now is the time to do the things you wouldn’t prioritize over climbing. For example, whilst battling with a long term shoulder problem, I went to India, did a 10-day meditation course and climbed a 6000m peak.

And maybe there are still opportunities within climbing – a lot of injuries don’t actually stop us being active altogether. Could you do low-intensity mileage, climb with a different grip type or do isolated training? This could be an opportunity to work on a weakness, and you may even end up a better climber in the long run.

Focusing on the opportunities we have (and not those we don’t have) helps us to be present; it brings our attention to what we can do now, rather than focusing on what has happened or what will happen when we’re recovered. This helps us to be positive, grateful and in some sense empowered, rather than ruminating over what is beyond our control.

A lot of students on our online courses have taken their injuries as an opportunity to work on mental training, much of which doesn’t require us to be on top climbing form. In fact, reading this article is a form of mental training – a bit of reading and inquiry helps you consider your mindset and reframe your injury. Good work!

How to get a perspective on your climbing injury

It’s often hard to see beyond our injuries, especially when they have a severe impact on our climbing lives. A broader perspective can be helpful here. Ask yourself: How long have you been climbing? How long will you be a climber for? With this in mind, where will this injury sit in the grand scheme of your climbing career?

Often a six-month injury can feel like a long prison sentence – we can’t go climbing and we’ll return to poor form. But if you removed a six-month chunk from your past or future climbing, it’s unlikely that your climbing career would be unrecognisable. And when we consider mental training along with physical activity, movement and technical skills, the injury period doesn’t have to be a complete absence of learning or climbing progression.

Get a clearer picture of your climbing injury

Part of the challenge of an injury is often in the unknowns. At times we respond to these unknowns before we know what the challenge really is. It’s hard to intentionally shift our mindset when we don’t know what we’re facing – we end up flitting between various possible outcomes and carrying the cumulative stress of each.

With some self-awareness (and attentional control and mindfulness practice) we can notice these thoughts and manage our response to them. Can we get expert advice on our injury to turn these unknowns into ‘knowns’? Can we accept unknowns and trust in our ability to deal with whatever outcome? This may be a lot harder than it sounds, and may require deep work to cultivate a mindset and create a stable sense of self-worth so that we can be ‘OK’ whether we reach our climbing goals or not.

Setting goals around your injury

When we have a better idea of our prognosis, we can set goals to work towards. This can help us measure, and therefore recognise, progress. It also directs our efforts and helps us adjust our expectations. Remember to set longer-term goals and intermediate stepping-stone goals. Also consider goals that are more process-based and help you to recognise progress even when a distinct goal isn’t met. For example, improving confidence in an injured finger, or improving your calm and acceptance around an injury.

Be adaptable and loosen expectations around injury

Consider the expectations you have around your injury. Sometimes these are expectations of recovery, of climbing or yourself. Whose expectations are they anyway? How do you feel when someone asks you how you’re climbing? Do you hasten to tell them you’re injured and lower their expectations? Or is it frustrating to talk about your injury? This was challenging for me as a professional climber because people had high expectations of me and often didn’t know I was injured; it became harder to manage my fear of what other people think which compounded the challenge of injury.

Exploring these questions can tell you where your expectations are coming from and how they’re serving you. Perhaps you still want to meet other people’s expectations of you as a climber, or you don’t want to lose status while you’re injured. Or perhaps you still expect to meet your own goals, or you identify as a strong climber despite being injured.

Once again, we can remind ourselves that climbing is a tough sport and the risk of injury is part of what it means to be a climber. Part of respecting the risk and challenge in climbing is to be flexible in our expectations of what happens when we climb: sometimes we send, sometimes we don’t, sometimes unfortunately we get injured.

Look after your body – and your mind – while you’re injured

Climbing is often a big part of how we look after ourselves, so it’s easy to see how an injury could change our healthy lifestyle balance. You’re not getting the endorphins you normally get from climbing or the rest of your exercise routine, and the chances are being injured isn’t what you had planned for yourself. Eating well and staying active where possible will benefit your mental health just as they benefit your physical health and recovery.

On top of that, mindfulness and meditation, mental training and conversational coaching are all ways of looking after our mental health that aren’t reliant on your physical form. Your mental health is important on its own, but a negative emotional state can also affect our adherence to training or rehab exercises. Furthermore, mental states of patients have been shown to affect recovery outcomes, specifically in the case of depression (Kellezi et al., 2017). This means looking after our mental health is more than just a nice idea – it’s part of our recovery and our overall well-being.

Do you have the necessary support around you now that you’re not going to the climbing wall or the crag? Could you seek extra support at this time? Socialising and being around friends is important for mental health; if climbing is your main form of socialising, make sure you seek alternatives or even continue to go to the crag as a spectator. I know that watching others climb when you can’t can feel heartbreaking, so I’ve found it useful to do something else at the crag such as photography or film. This can be a great way to feel involved and have something to do without climbing. I think many a photography career has begun this way!

Carlo Traversi on Magic Line, Yosemite Valley

Nurture your mindset for injury and share it with climbing friends

Consider how you talk about your injury to your friends and those around you. How we talk about our climbing or our injuries reflects our own mindset and motivations, and when in conversation it’s easy to slip into another person’s set of values or beliefs. That means that our own reframing and mindset shifts are easily undone when we don’t stick to our own authentic values. Don’t be afraid to tell your friends you’re taking a step back from climbing, finding value elsewhere, not fixated on performance or not letting your injury define your wellbeing if that’s what feels authentic to you.

A strong psychological recovery from injury

Don’t forget that alongside a physical recovery comes a psychological one. It can take time to build the confidence that we won’t get injured again, and fear of injury needs to be dealt with just like other fears in climbing such as fear of falling.

If your injury occurred during a fall or an accident, this may have been traumatic and will take time and patience to recover from. Just as you adjust the physical challenge when you return to climbing from injury, you need to adjust the psychological challenge too – you won’t be as comfortable on a runout or highball after an accident, or after taking so much time off.

And whether we’ve physically recovered from an injury or not, our bodies will be different from before the injury, which will have an effect on our confidence. After my shoulder operation I wasn’t the same climber anymore: I didn’t have the same body, the same pulling power and most of all the same confidence. Be careful not to overlook the psychological challenge of climbing or the psychological component of your injury.

A healthy mindset for injury prevention

It’s important to consider how your mindset might have contributed to your injury. It’s easy to focus on the proximal cause of your injury, but do you have a healthy mindset and a healthy relationship with climbing? Injuries are often a sign that we needed to take a break, or sometimes they tell us that we hadn’t acknowledged the risk. Research from the Technische Universiteit Eindhoven showed that ‘obsessively passionate’ runners were at a higher risk of injury, whilst those that were able to detach from their sport were at lower risk (van Iperen, 2022).

How did your mindset contribute to your injury? Do you know when to stop pushing yourself or do you *need* to keep trying? For me, my capacity to try hard is both a huge asset for my climbing and a considerable risk for injury. Throughout this article I’ve encouraged you to consider how your mindset is serving you. This might be the moment to consider your attachment to climbing and its relationship to your self-worth. How does it feel *not* to climb? Having a powerful motivation for climbing is different from having a sustainable motivation conducive to performance and enjoyment (and one that you can let go of when it’s appropriate to).

Clearly, there are countless ways that our psychology can contribute to an injury or its recovery, and there are plenty of ideas in this article that will steer you towards a healthy mindset for climbing. The most important thing is to consider your experience through a psychological lens when injured or working to prevent injury, and not only consider the physical components of your climbing. If you’re interested in investing more in your mental training for climbing or giving yourself a mindset makeover, check out our free webinar.

References

- Kellezi, B., Coupland, C., Morriss, R., Beckett, K., Joseph, S., Barnes, J., Christie, N., Sleney, J., & Kendrick, D. (2017). The impact of psychological factors on recovery from injury: a multicentre cohort study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 52(7), 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1299-z

- Van Iperen, L. P. (2022). Psychological predictors of recreational runners’ health: Self-regulatory processes and running-related injuries, fatigue, and vigour. Phd Thesis 1 (Research TU/e / Graduation TU/e), Industrial Engineering and Innovation Sciences. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/ccd6ac5d-fa9a-499a-9d79-6947c78af134

About the Author

Hazel Findlay is a professional climber and mental training coach. As well as having 9a, 5.14c trad and numerous big wall ascents to her name, she is the founder of Strong Mind Climbing – the leading provider of online mental training courses for climbers.

Hazel and her partner Angus have coached thousands of climbers through their sell-out online courses and 1:1 coaching.

Strong Mind offers acclaimed courses in fear management and performance psychology. Check out their instructive free webinar on performance here.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.