The Importance of Our Center: Outlining Thoracic Mobility and Core Stability

- “Poor weather”

- “Can’t find a belay partner”

- “Poor route setting”

- “Lack of equipment”

- “Expensive gym memberships”

- “Gym hours that do not coordinate with my schedule”

The list goes on…

Have you found yourself using one of these ~excuses~ to account for poor climbing, poor performance, or just feeling stagnant? We face many obstacles when it comes to achieving what it is that we want – in personal lives and climbing careers alike. Sure, sometimes these obstacles are based on factors outside of our control, but it is all too easy to let excuses account for a personal lack of success on the wall. However, by evaluating your own movement, you may find that you have internal obstacles that are impeding your climbing ability. These are the ones that we can target, be proactive about changing, and climb better as a result. Have you ever been reaching for a hold and thought “If only I were able to reach my arm out just two inches further?” Have you ever experienced pain in your back from attempting a move without stability and control? Addressing the deficiencies in your core can help enhance your climbing. By creating a more stable base, we are better able to initiate movements and maintain body control through each move. The freedom that comes with improving our mobility means we won’t have to consider the risk of placing our extremities in vulnerable positions or being reliant on extremity strength to hold us to the wall. Keep reading to better understand the mobility of our thoracic spine, the stability of our core, and how improving both can take your climbing to the next level!

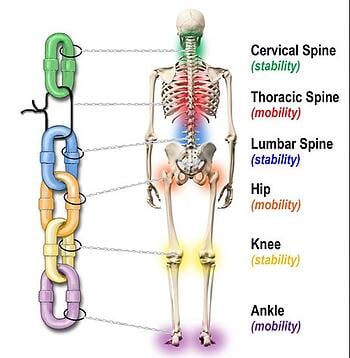

To the top, you will see a model highlighting a concept known as regional interdependence (RI). What RI outlines is how seemingly unrelated impairments in a different anatomical region may actually be the cause or culprit behind your pain.1 For example, a runner’s hip pain may actually be derived by limitations in their ankle. This theory views all regions of our body as being “musculoskeletally linked” to each other. Maintaining the mobility and stability aspects will allow for optimization of movement. The majority of rock climbing injuries take place in the extremities, which require extensive prevention and rehabilitation.2 If we are able to maintain stability in our core, regardless of our center of mass (COM), and capitalize on our thoracic mobility, then perhaps we wouldn’t be putting our extremities in vulnerable positions, as they often are when injured. The better control we have of our COM the less exertion we place on our fingers, forearms, and shoulders and subsequently reduce our risk for injury. As a plus: a stronger core and better motor control translate to our generation and force output at our extremities. “The muscles that are typically associated with the core allow for the transference of torques and angular momentum during the performance of integrated kinetic chain activities, such as kicking or throwing.”3 In fact, Willardson suggests that increasing an athlete’s core stability will result in a better foundation for force production in the upper and lower extremities. The ability to generate “big upper body power” is a standout item in what sets advanced rock climbers apart.4,5 I would like to think core stability had a hand in their production of upper extremity power and research would support this; better core stability translates to greater production of upper extremity power.

The core is the center of most kinetic chains in the body and the basis for nearly every move a climber makes; it should therefore be trained accordingly. There are many plans available that outline core workouts for the athlete, but the key is to direct yourself into functional static and dynamic positions that are replicated in the body postures of climbing.To better understand the “why” behind my emphasis on developing your core, let’s outline the purpose of these segments of our body.

The Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine is composed of 12 vertebrae with prominent spinous processes and minor transverse processes. The latter allow for larger rotational movements to occur at these thoracic spine vertebral segments. The thoracic spine is naturally kyphotic, placing us in a vulnerable position to be pulled further into kyphosis and give us the “rock climbing hunchback” if we do not perform exercises that work antagonistically. Bo Herris wrote an excellent article outlining some useful antagonistic movements and you can reference it here . 6

The Core

“Core” is a very broad word encompassing multiple muscles and, in fact, includes much more than just our abdominals. It includes muscle attachments from the ribs all the way down to into our hips. More than just the abdominals it is the diaphragm, pelvic floor, and lumbar multifidus muscles. For the purpose of this article, I will focus on the abdominal core. We have both an inner core and outer core. Think about the inner core as your stabilizers and the outer core as your power movers, in addition to providing stability. Our primary stabilizer in the abdominals is the transversus abdominis. Rectus abdominis allows for compression. Internal and external obliques are activated by rotation and leaning. All of these are important for climbing due to the constant maneuvering of our extremities. By engaging the core we can maintain stability despite adjusting our COM as we meet new holds and navigate up the wall. The greatest role of the core in climbing is not necessarily to be the prime mover, but rather a group of nearly exclusive stabilizers. In climbing, they are best used to control the movement rather than to initiate it – to reduce loads on vulnerable tissues. Keep this in mind as I get into exercises and progressions.

In short:

- Flexion: Rectus abdominis

- Extension: Erector spinae, trapezius and rhomboids

- Rotation: External oblique, internal oblique, trapezius and rhomboids

- Stabilization: Transversus Abdominis, Lumbar Multifidus, Diaphragm, Pelvic Floor

A weakened core and decreased thoracic mobility could manifest themselves in a variety of ways: inability to maintain a hold with a rotated trunk, experiencing pain in your shoulder or elbow as a result of being too far off the wall, and displaying a hunchback while climbing or observing others in the gym. A slouched posture weakens and strains our core muscles. If you sit at a desk for several hours a day, regardless of how you feel about your climbing ability, I would highly suggest adopting some of these movements to counteract the strains on your back as a result of your sitting posture.

Assessment

Thoracic Assessment

One way we can objectively assess and determine thoracic rotation and extension is through a lumbar locked thoracic rotation movement.

Positioning: Begin in a quadruped position. Shift your hips back toward your heels and place both forearms on the ground in front of you. Your elbows should be between your knees. In this position, we have locked out the lumbar spine so that we can ensure the motion is coming from the 12 vertebrae of the thoracic spine.

Motion: Place one of your hands in the small of your back. Rotate towards that side. Imagine you are in a tube and must rotate in place – as far as you can go without compensating.

Common Compensations: side bending, having your leg lift, or masking limited ROM with increased shoulder mobility. Eyeing the ROM using the elbow may be deceiving due to shoulder mobility. [insert video here to demonstrate how someone could self assess their mobility]

ROM Measure: Measure from acromion to acromion. We are striving to see 50 degrees.

Core Assessment

A great assessment for core stability with rock climbers can be found in a previous blog post written by Dr. Kevin Cowell named “Climbing-Specific Body Tension: A Systematic Approach for Assessment & Progression.” 7 His article reviews an assessment that has been developed as a functional strength and performance test (Modified “Bunkie” Test). It examines the strength capacity of the core, deep trunk musculature, and other critical muscle groups of the upper and lower body used to develop body tension. Otherwise known as the muscles most responsible for our core’s stability. It includes 5 specific testing positions that challenge aspects of body tension associated with climbing.

Exercises

The following exercises provide some standard stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises. In addition, there are progressions into more functional climbing-specific exercises to implement into your climbing regimen. All exercise descriptions and recommended prescriptions are found within the video links. Choose one, choose all, choose whatever feels best and produces the best results for you!

Exercises to improve Thoracic Rotation:

The below exercises all improve thoracic rotational mobility. As they are listed, the exercises increase in functionality as you move down the list, choose 2-3 of these to work between including in your current warm-up.

[Open Book]

[Thoracic Rotation (W Resistance Band of Assistance]

[Brettzel 1.0:]

[Half Kneeling T Spine Rotation]

[Half Kneeling at Wall]

Exercises to improve Thoracic Extension:

The below exercises all improve thoracic extension mobility. As they are listed, the exercises increase in functionality as you move down the list, choose 2-3 of these to work between including in your current warm-up.

[Thoracic Extension over Foam Roller]

[Dynamic Overhead Arms on Foam Roller]

[Thoracic Extension w/ Resistance Bands Pulls]

[Thoracic Extension over Foam Roller – Weighted]

Exercises to promote Core Activation and Stabilization: 8

The below exercises all target abdominal muscular stability in a climbing-specific fashion. As they are listed, the exercises increase in functionality as you move down the list, choose 2-3 of these to work between including in your current warm-up.

[Inverted Planks]

[Side Planks w/ Rotation]

[Trunk Stability with Arm Mvmts: Plank Pull Downs]

[Planks with Sandbag Pull Throughs]

[Plank w/ Unilateral Oblique Knee Raises]

[Plank w Contralateral Oblique Knee Raises]

[Hanging Single Leg (Unilateral Oblique Curl + Knee Raises)]

[Hanging Single Leg (Contralateral Oblique Curl + Knee Raises)]

[Hanging Double Leg Oblique Crunch]

Connect It All! (Core and Thoracic)

[Combined: Upper Extremity Rolling (Flexion and Extension)]

[Combined: Lower Extremity Rolling (Flexion and Extension)]

Climb on!

The Research

- Sueki, D. G., Cleland, J. A., & Wainner, R. S. (2013). A regional interdependence model of musculoskeletal dysfunction: research, mechanisms, and clinical implications. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 21(2), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000027

- Rauch, S., Wallner, B., Ströhle, M., Dal Cappello, T., & Brodmann Maeder, M. (2019). Climbing Accidents-Prospective Data Analysis from the International Alpine Trauma Registry and Systematic Review of the Literature. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(1), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph27010203

- Willardson, JM. Core stability training: Applications to sports conditioning programs. J Strength Cond Res 21:979-985, 2007.

- Shinkle J, Nesser TW, Demchak TJ, McMannus DM. Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(2):373-380. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822600e5

- Watts PB, Martin DT, Durtschi S. Anthropometric profiles of elite male and female competitive sport rock climbers. J Sports Sci. 1993;11(2):113–7. Pmid:8497013.

- Herris, B. (2019) Avoid the Rock Climbing Hunchback. The Climbing Doctor. https://theclimbingdoctor.com/ hunchback/

- Cowell, K. (2021). Climbing-Specific Body Tension. The Climbing Doctor. https://theclimbingdoctor.com/climbing-specific-body-tension-2/.

- Saeterbakken, A. H., Loken, E., Scott, S., Hermans, E., Vereide, V. A., & Andersen, V. (2018). Effects of ten weeks dynamic or isometric core training on climbing performance among highly trained climbers. PloS one, 13(10), e0203766. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203766

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

This article has provided an outline for self-assessment and interventions for a climber’s thoracic spine and core. I have been explicit in the importance of both mobility as well as the stability that derives from this body region and the vital role they play in every move made on a wall. While I encourage you to make adjustments to your warm-up, off-wall workouts, or cross training as you see fit with this article, by visiting a physical therapist you would be offered individualized care for your individual needs. Physical therapists are the movement and musculoskeletal experts who can analyze your biomechanics and provide personalized care. Simply put, the desire to move better is all the reason you need to see a PT!

About the Author

My name is Christin Donahoe and I am a Cleveland, OH native. Currently, I am a second year DPT student at the University of Evansville and I have an undergraduate degree in Interdisciplinary Studies (Spanish and Exercise Science) from UE. I became hooked on rock climbing due to the inherent intersection of the mental and physical challenges that come with rock climbing. It offers me a space to be creative, innovative, and physically active. In addition to climbing, I enjoy running, cycling, and yoga. I am Level I SFMA certified, a member of the APTA, and passionate about functional movement and the female athlete.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.