Why Do You Have Stiff Shoulders Climbing

This article will focus on why rock climbers have stiff shoulders. While analyzing the climbers’ neck and shoulder pain during a clinical exam, immobility assessment is a key component.

| Muscle Length | Joint Mobility | Range of Motion |

|---|---|---|

| Pec Major | Humeral AP Glide | Shoulder Flexion |

| Pec Minor | Humeral Inferior Glide | Shoulder Abduction |

| Latissimus Dorsi | Thoracic PA Glide | Shoulder Internal Rotation |

| Teres Major | Cervical PA Glide | Shoulder External Rotation |

| Posterior Cuff | Scapular Mobility | |

| Cervical Flexion | ||

| Cervical Extension | ||

| Cervical Rotation |

In the table shown above, you can see different common mobility deficits among rock climbers. Apart from these, there are many other mobility deficits that a rock climber may have. These key factors can be examined in isolation or combined, and composite motions may also be necessary when assessing different components of a rock climber’s mobility. We will discuss the key components of a climber’s mobility below.

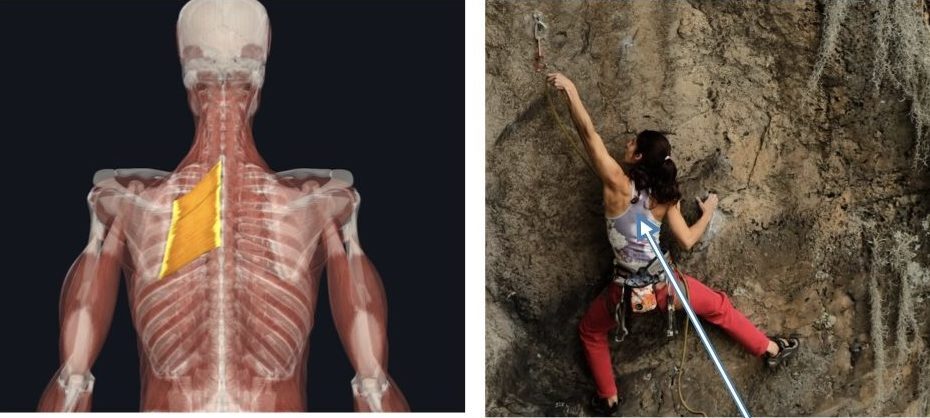

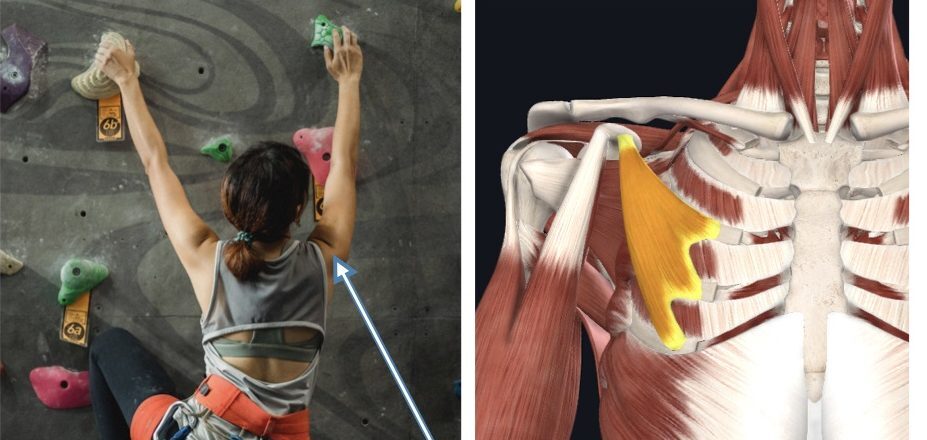

Scapular Mobility

First, we will discuss scapular mobility. In the illustration shown above, The clinician grasps the scapula and then shifts their body weight creating scapular abduction in upward rotation. During the technique, the clinician assesses whether there is any resistance of the tissues. So which tissues can limit this motion?

A mobility deficit in the Rhomboids may lead to inadequate scapular protraction and upward rotation when a climber is reaching for a hold or looking to clip a draw.

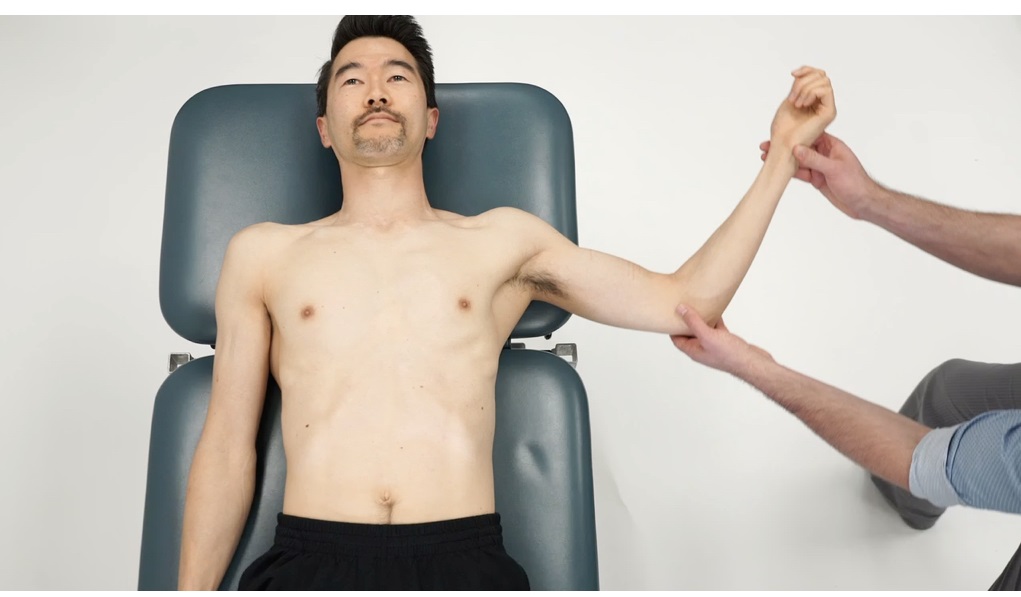

Humeral Rotation

Now let’s discuss humeral external rotation. What are you biasing when you test the shoulder at different angles, i.e., 45 degrees, 90 degrees, 135 degrees, and 180 degrees?

Mobility deficit in any of the internal rotators of the shoulder can lead to inadequate humeral external rotation while the climber is reaching, and can lead to a decreased subacromial space.

The subscapularis muscle, pectoralis muscle, Latissimus dorsi, and Teres major are the internal rotators of the shoulder. When we’re testing at 45 degrees, we are biasing the subscapularis muscle. While at 90 degrees, we are biasing the pectoralis major clavicular fibers as well as the joint capsule, and at 135 degrees, pectoralis major sternal fibers. To further differentiate Latissimus dorsi and Teres major, we can take the climber’s humerus into greater degrees of shoulder flexion, i.e. up to 180 degrees. If the scapula slides away from the spine or the thorax, we can suspect that Teres major is contributing to this mobility deficit. If we notice that the climber arch their spine or flare their rib cage during shoulder flexion, we can determine that potentially latissimus dorsi is playing a role.

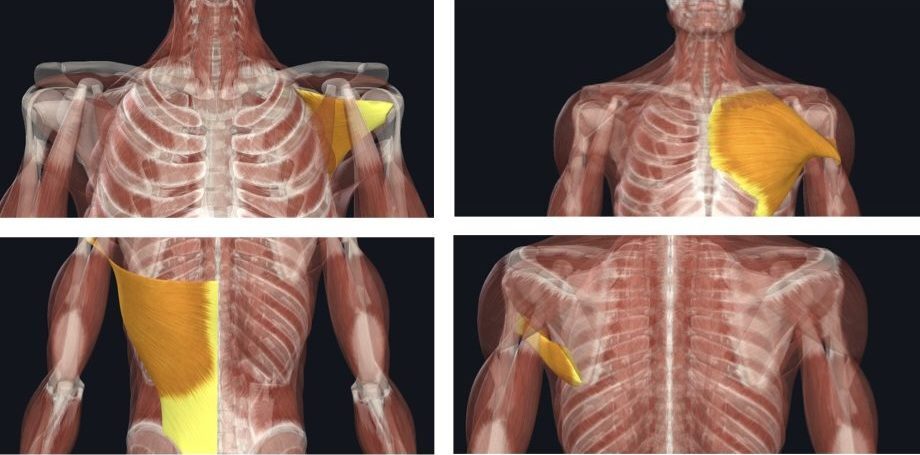

Pectoralis Major

The image shown below shows the muscle length assessment of pectoralis major (both the clavicular and the sternal fibers)

During this assessment, the clinician placed the climber’s arm across their chest and grasped the distal end of the humerus. The clinician then stabilized their arm into their thorax to prevent rotation, and they brought their humerus into horizontal abduction. Then the climber raises their arm into 135 degrees of humeral abduction, and the clinician tests horizontal abduction again. Checking for tissue resistance, as well as overall mobility past neutral, it is fairly common for climbers to have excessive mobility in their pectoralis clavicular fibers in the 90-degree position to horizontally abduct past neutral.

Climbers tend to have an excessive flexibility of the clavicular fibers and inadequate flexibility of the sternal fibers.

However, this is not a natural movement during climbing. Sometimes, if you have to stem with your upper body, you have to hyper-angulate your shoulders. But this excessive mobility can cause capsular strain and can leave the entry joint capsule lax for rock climbers. In contrast, when a climber’s shoulder is taken up to a 135-degree position while testing the sternal fibers and the pectoralIs major, climbers often have shortness or stiffness of these muscle fibers. Then it would be beneficial to stretch out the muscles at a 135-degree position because it is a common position during climbing. Since the muscles are stiff and the shoulder is unable to get to that neutral position, it is a great way to increase the mobility of the pectoralis muscle without causing excessive strain on the joint capsule.

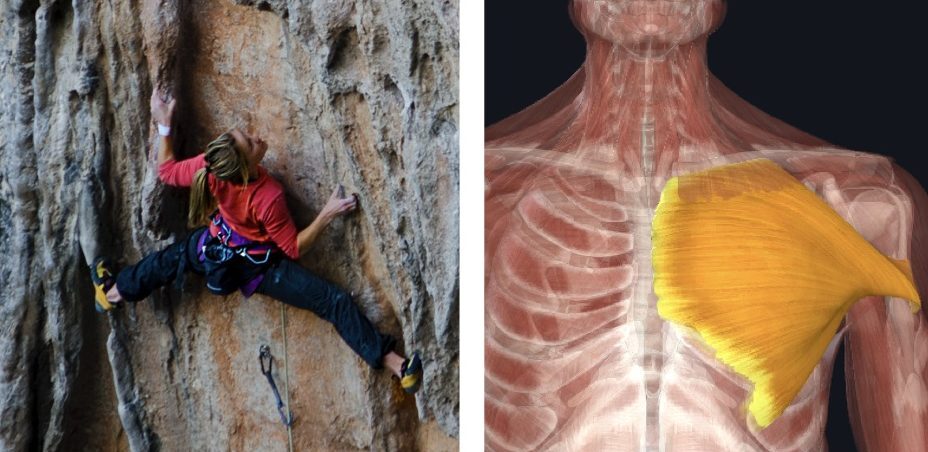

Pectoralis Minor

Pectoralis minor is another muscle that often presents with a mobility deficit with rock climbers. In the picture above, you can see the assessment of pectoralis minor. The climber’s acromion is marked with a red dot, and a measuring tape can be used to measure the distance from the acromion down to the table. Normal measurements are 2.54 centimeters or one inch. While performing this technique, you can either extend the elbows or bend them. If you perform this technique with the elbows extended, make sure that the scapula isn’t anterior tipping from a short biceps short head or a short biceps long head. Since the bicep short head attaches the coracoid process, and the biceps long head attaches the superior glenoid tubercle, a short muscle can cause anterior tipping of the scapula and give the perception of a stiff pectoralis minor.

A mobility deficit of the pectorals minor can lead to inadequate posterior tipping of the scapula while climbing and reaching leading to glenohumeral hypermobility and a fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.

How does this relate to rock climbing? Immobility deficit of the pectoralis minor can lead to inadequate posterior tipping of the scapula while rock climbing, which often occurs during reaching. This can lead to excessive glenohumeral hypermobility and a fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint. As you can see on the image above, a stiff pectoralis minor can cause a decreased posterior tipping of the scapula, which then means that the Glenohumeral joint has to excessively flex. With excessive flexion of the glenohumeral joint, you will notice asymmetric creases in the posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint, which you can compare side to side.

This is often easy to visualize in the clinic as well with having a climber stand in front of you, and go into bilateral shoulder flexion. If you notice inadequate posterior tipping of the scapula and excessive fulcrum in the posterior aspect of the humerus, then you will need to follow that up with some type of test to assess if there is excessive hypermobility of the glenohumeral joint. The climber should be put on a pectoralis minor mobility program as well as a glenohumeral joint stability program.

Posterior cuff

A mobility deficit that climbers often present with is a short or stiff posterior cuff or posterior joint capsule. In the picture above you can see a modified Tyler’s test. The clinician will stabilize the lateral border of the scapula into the table, don’t grasp the climber’s distal radioulnar joint, and they will horizontally abduct their humerUS, with a normative value of the elbow reaching the nose. The clinician will appreciate the end feel, whether it is a firm capsular end feel from the joint capsule, or a firm muscular end feel from the posterior rotator cuff. They will need to determine which structures are creating that mobility deficit.

A mobility deficit of the posterior cuff can lead to an anterior humeral glide in climbers through obligate translation causing anterior shoulder pain. The humeral head translates in direction opposite of tightness.

A mobility deficit of the posterior cuff can lead to an anterior humeral glide in rock climbers, through a concept called obligate translation. This was identified in a Harriman study and it showed that tightness of the posterior cuff can lead to anterior shoulder pain and anterior migration of the humerus. The humeral head will translate in the direction opposite of the tightness. Imagine a slingshot or some type of hammock is squeezing the humerus forward from stiffness or shortness of the joint capsule or the posterior rotator cuff.

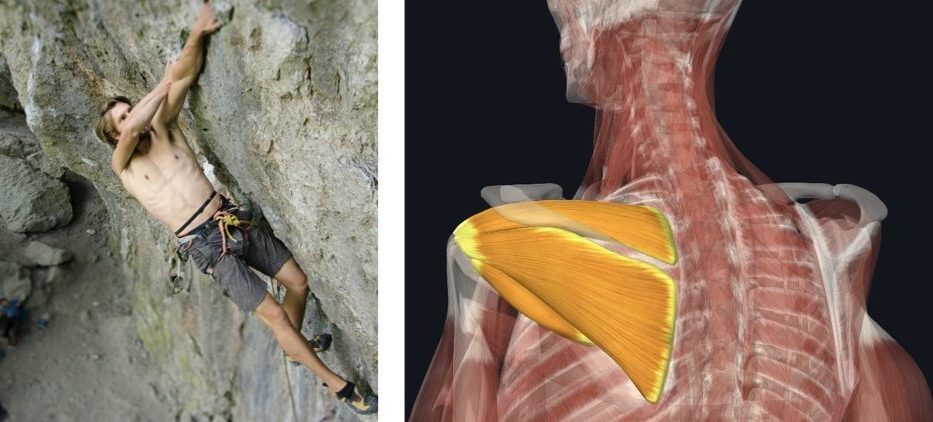

Latissimus dorsi

The latissimus dorsi is a muscle that needs to be screened in rock climbers. To assess the muscle length of the latissimus dorsi, the clinician will grasp the distal humerus of the rock climber, and they will monitor the rib and the lumbar position into end range humeral flexion. You can see in the picture above, as the climbers are taken into end range humeral flexion, the rib cage lifts, and the spine arches. We can then assess the relative flexibility of the muscle by stabilizing the thorax and the rib cage and taking the climber into the end range. And then they no longer can achieve their full mobility.

Short Latissimus Dorsi

Short Latissimus Dorsi

In the first example, we talked about the relative stiffness of the latissimus dorsi muscle. As the clinician brought the climber into humeral flexion, we saw that his rib cage expanded and the lumbar spine arched. In the second example, when the clinician stabilized the rib cage, the climber was no longer able to achieve maximal shoulder flexion. This indicates a muscle with a mobility deficit. This concept of relative stiffness is very important, with rock climbers.

A mobility deficit in the latisumus dorsi can limit overhead reaching range of motion and cause a climber to loose anterior core tension while reaching secondary to an anterior pelvic tilt.

I used to always think that rock climbers have very tight muscles, and I would overstretch these muscles. And the real issue was their relative stiffness. The stiffness of their pectoralis muscles was greater than that of their midsection or their court. When the climber was climbing and reaching into these end range positions, they would be hyperextending and fulcrum through their lumbar spine, and then start to develop some overuse injuries and their shoulder.

We went through a lot of different mobility assessments for climbers. There are many other components that I look for in rock climbers when I’m assessing mobility. But these are a few good ways for you to start understanding the main muscle groups that can get short and that can get stiff with rock climbers, and how to assess them in a rock climbing-specific way.

How to Treat Shoulder Stiffness

If a climber has shoulder stiffness in one direction or related to one muscle group, you can isolate that deficit into a specific exercise. For example, if a climber has a restriction into internal shoulder rotation, it is possible their shoulder joint capsule or rotator cuff muscles are stiff. And as long as the shoulder isn’t gliding forward and causing stress on the front of the shoulder (as discussed earlier in the article) you can perform the exercise below to regain mobility internal internal rotation

However, if they have pain in the front of the shoulder and it is made worse when performing the composite exercise, you can modify the stress on the front of the shoulder by taking the humerus out of extension and flexing it in front of the climber in a passive stretch (although it can also be performed actively) called a sleeper stretch.

Courses for Medical Providers and Coaches

Want to learn more ways to assess, diagnose and treat climbing shoulder and neck injuries? Check out the online course below to expand your knowledge and skillset in the management of rock climbing injuries. Click the course to learn more!

About The Author

Jared Vagy is a doctor of physical therapy who specializes in treating climbing injuries. He is the author of the Amazon #1 best-seller “Climb Injury-Free,” teaches Climbing Injury Professional Education for Medical Providers, and is the developer of the Rock Rehab Protocols. He has published numerous articles on injury prevention and lectures internationally. Dr. Vagy is on the teaching faculty at the University of Southern California, one of the top doctor of physical therapy programs in the USA. He is a board-certified orthopedic clinical specialist. He is passionate about climbing and enjoys working with climbers of all ability levels, ranging from novice climbers to the top professional climbers in the world.

For more education, check out the Instagram page @theclimbingdoctor

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.