Physical Therapy for Climbers after Anterior Shoulder Instability Surgery

I first subluxed my shoulder almost thirty years ago during my freshman year of high school soccer. A subluxation is where the head of humerus, the ball of the upper arm bone, partially moves out of the shoulder socket and then back in. I used my shoulder carelessly to body check an opponent to win the ball. Instinctively, I threw it back in place with a backward motion of my trunk and the resulting momentum caused the humeral head to slide back into place. Years later, I subluxed again. It happened a few times bouldering overhung problems and once golfing with a bad follow-through after a tee-off drive. Eventually, I noticed my shoulder felt vulnerable with certain overhead movements in climbing, yoga, and working out. I tried physical therapy twice which helped build some confidence and trust, but the apprehension was still there. The fear of “popping out” prevented me from climbing to my fullest potential. I dreaded what seemed inevitable: surgery. MRI findings reported a “probable tearing of the anteroinferior labrum with small chronic appearing Hill-Sachs deformity.” What does this mean? My orthopedic surgeon performed a quick history and exam and to no surprise, recommended surgery.

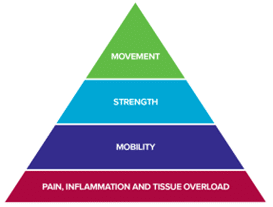

More than likely, after recurrent subluxations or dislocations, you will need surgery. Recovery, rehab, and return to climbing after surgery takes months and is highly dependent on compliance and participation in physical therapy. This article will guide the rock climber though a rehabilitation program after Arthroscopic Anterior Stabilization with or without Bankart repair and get them back to crushing their projects.

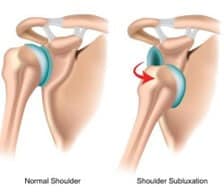

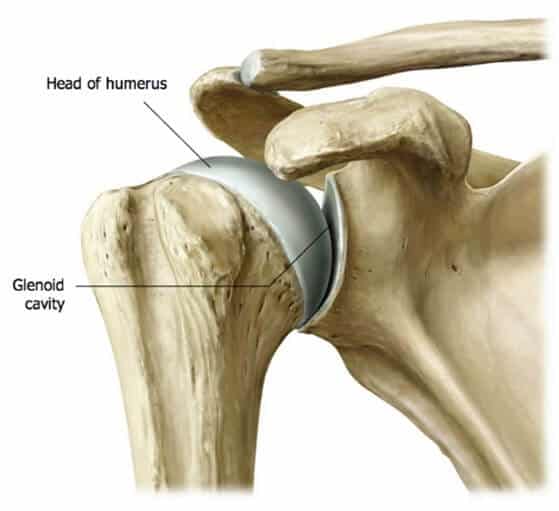

Figure 1

How does the shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, become unstable? The glenohumeral joint becomes unstable when the ball or head of the humerus is outside of its normal position in the socket. (See Figure 1.) This instability can happen after it is subluxed repeatedly, dislocated, or congenital. You get to a point where the net force on or across the glenohumeral joint is so great that it cannot be compensated for by the anatomical structural stability of the shoulder, which include the bones, labrum, ligaments, joint capsule, and the rotator cuff muscles.

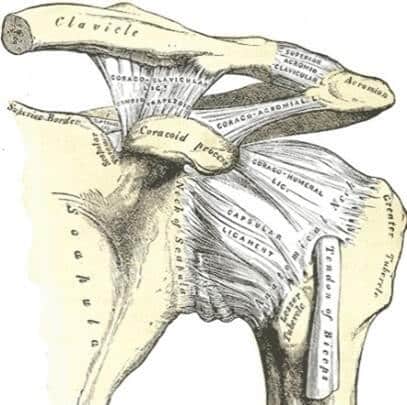

The shoulder’s bony structures provide little to no structural stability by themselves. There is a very small and shallow socket or glenoid cavity that articulates with a large ball (head of humerus) like a golf ball on a tee. (See Figure 2.) This makes the shoulder prone to being unstable. The “static” stabilizers of the shoulder joint consist of the joint capsule, ligaments, and labrum. The labrum is a thick ring of cartilage that surrounds the edge of the glenoid, essentially deepening the socket 50%-75% which helps keep the ball in place. The joint capsule is a sac made up of ligaments and connective tissue that encapsulates the joint. (See Figure 3.) The intricate arrangement of ligaments connects the humerus to the glenoid, providing a main source of stability for the shoulder.

Figure 2

Figure 3

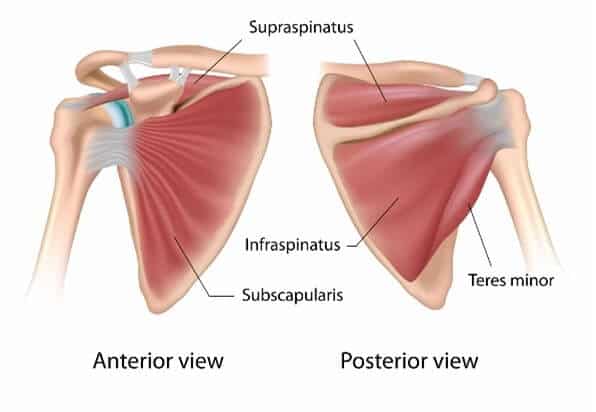

The rotator cuff muscles are the “dynamic” stabilizers of the shoulder. (See Figure 4.) They center the humeral head on the glenoid by pulling the head of the humerus into the glenoid fossa. (See Figure 5.) The tendons of the rotator cuff muscles are intimate with the joint capsule.

Figure 5

Figure 4

The most common symptom that people get with shoulder instability is that they feel like their shoulder is popping out of their socket, the same symptom I felt after multiple subluxations. This is due to trauma, microinstability, or congenital. Shoulder subluxation or dislocation can happen with a traumatic event such as a Fall Onto an Outstretched Hand (FOOSH). This usually results in damage to the supporting structures of the shoulder (i.e. labrum, ligaments, joint capsule, bones) which requires surgery for the joint to become stable again. Microinstability can happen from repetitive microtrauma where over time, repetitive movements such as throwing weaken the structures of the shoulder. If the joint capsule gets stretched out and the shoulder muscles become weak, the ball of the humerus begins to slip around too much within the shoulder. This is common among baseball pitchers, volleyball players, and swimmers. Finally, individuals can be genetically predisposed to having unstable shoulders due to lax ligaments. This is often known as Multidirectional Instability (MDI) that becomes symptomatic over a course of time without specific mechanism of injury other than repetitive use.

Figure 6

The humeral head that fits into your shoulder socket can sublux or dislocate in several directions depending on how it is loaded. Most subluxations or dislocations (~90% incidence) occur through the front of the shoulder. For the purposes of this article, we will be focusing on anterior or frontal instability. In many cases (90% or greater) of anterior subluxation or dislocation individuals have a Bankart lesion which requires surgery. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 7

Figure 8

A Bankart lesion is when the labrum, a connective tissue ring around the socket, pulls off the front of the socket. It can also bring damage to the connection between the labrum and joint capsule. You need an MRI to shed light on what soft-tissue damage you have suffered. This usually happens when the arm is outstretched, abducted, and externally rotated. Imagine if you’re biking and need to make a right hand signal with your arm. (See Figure 7.) A “bony” Bankart is where a portion of the glenoid surface breaks off with the labrum. Additionally, during dislocation the back humeral head can impact the front the glenoid rim, or edge of the socket, causing a compression fracture or depression defect on the humerus called a Hills Sacks lesion. (See Figure 8.) Other associated pathology can occur with anterior dislocation including a traction injury of the brachial plexus and axillary blood vessels. If you are a patient being seen by a physical therapist, the therapist should follow up with a neurological screen to see if there are lingering nerve palsies or damage for a better idea of prognosis or additional medical work up.

Signs and symptoms for anterior shoulder instability

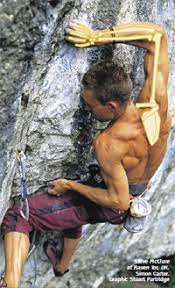

Some of the common associated findings with anterior shoulder instability typically involve a traumatic event, for example a FOOSH, direct hit to the shoulder, or full dislocation. During the physical examination, there may be several signs that help form the basis for a diagnosis. With anterior shoulder instability you may feel diffuse pain over the anterior and posterior (back) of the shoulder with palpation. Palpation is when a health care professional uses their fingers and hands to feel and assess the anatomical structures of your body. You might also feel diffuse pain after a dislocation that reduces significantly after you have had your shoulder reduced or put back into its place by a health care professional. During the exam, active and passive range of motion can be highly variable depending on acuity. You may have full or near full range of motion with “guarding” later in recovery. Guarding is a physical or emotional protective response aimed at preventing pain or injury. This often presents as being unable or unwilling to move into end ranges of shoulder abduction and external rotation. The climber may feel pain or apprehension with certain overhead movements, where the shoulder is in 90 degrees of abduction and 90 degrees of external rotation with the elbow flexed. (See Figure 7.) This is the most vulnerable position for the shoulder. Personally, I felt vulnerable and apprehensive before a committing to a gaston (See Figure 9) or dyno. After an acute injury, you may have minimal motion and be unwilling to move. While testing your shoulder strength, it may be limited by pain, especially rotator cuff weakness particularly in external rotation and abduction. The most common sequela of anterior shoulder instability is recurrent dislocations or subluxations. Other complications include Bankart lesions, injury to the inferior glenohumeral ligament, Hill Sachs lesion, and “dead arm.” Dead arm occurs when the arm is in an abducted and externally rotated position, and you feel a sharp, anterior shoulder pain and numbness and/or tingling down the affected arm.

Figure 9

Assessment

Diagnosis of anterior shoulder instability is through a thorough interview, imaging, and a cluster of special tests. First, a health care professional will obtain relevant information about you, your current condition or chief complaint, associated symptoms, and history. Next, you will perform a physical examination which might include visual inspection, motion, strength, palpation, neurological screening, pain assessment, passive mobility testing, functional testing, special tests for the shoulder, and clearing procedures for neighboring joints. A health care professional will interpret these signs and symptoms from the subjective interview and objective examination that may warrant further diagnostic testing such as imaging and/or referral to another health care professional.

The most common scenario is that you’ve had your shoulder reduced after a dislocation. A few weeks after the injury, you’re in a physical therapy clinic. Your shoulder is feeling better with more movement and reduced symptoms and inflammation. At this point, we want to find out if the glenohumeral, or shoulder joint, is stable. The best cluster of tests for anterior instability are the Anterior Apprehension/Relocation test, Load and Shift, and the Sulcus Sign. The single best test is the Anterior Apprehension Test but it’s also the most aggravating. Save this test for last. This test is highly specific, which means that a positive test result is strongly predictive of anterior shoulder instability. If you see excessive anterior translation, you start to speculate what the anterior apprehension test might look like. If you find excessive anterior translation with the Load and Shift Test, you start to speculate what the Anterior Apprehension test might look like.

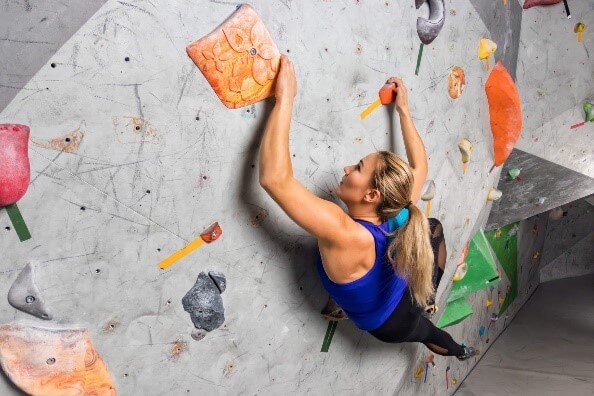

The Rock Rehab Pyramid

The Rock Rehab Pyramid is a framework developed by Dr. Jared Vagy to help climbers self-manage climbing injuries. The pyramid consists of four phases: 1) Pain, inflammation, and tissue overload, 2) Mobility, 3) Strength, and 4) Movement. This rehabilitation and injury prevention program begins at the bottom of the pyramid and progressively advances up until you fully recover. For more science-based, injury prevention and rehabilitation information designed specifically for climbers check out the book Climb Injury-Free.

Once a shoulder is subluxed or dislocated, it can become unstable and prone to future dislocations or subluxations. When an individual has a subluxation with no major nerve or tissue damage, the shoulder should improve quickly. Strengthening exercises may help to increase the stability of the shoulder joint. If you are going to manage conservatively, the four Ps of conservative rehabilitation described by Jobe1 can be utilized for nearly every post-operative recovery or progression relative to instability of any kind for the shoulder complex. The four Ps are the glenohumeral Protectors (rotator cuff), the scapular Pivoters (trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rhomboids), the humeral Positioners (deltoid), and the Propeller muscles (latissimus dorsi and pectoralis). If you had a dislocation or subluxation, you’re going to lose proprioception. It’s very important to do a lot of dynamic rhythmic stabilization techniques or perturbations as well as exercises that require the eyes to be closed as early as possible. A physical therapist can prescribe a home exercise program tailored to each person’s needs. In this article, we will focus on post-operative guidelines for Arthroscopic Anterior Stabilization (anterior capsule-labral repair).

Once you’ve had surgery to repair the anterior labrum and capsule, the rehabilitation is straight forward. Initially, the goal is to balance protection of the repair while initiating early range of motion to prevent long-term stiffness and pain. This is known as the protective phase. Clinical studies that advocate for initiating early range of motion have shown quicker return to functional range of motion and functional activity, with no increased instability.2 However, avoid being over-aggressive with range of motion and stretching early and creating synovitis. You will respect and protect appropriate tissues for 4-6 weeks by avoiding closed-chained positions and limit shoulder external rotation. Once you are out of the protective phase, then you want to start working on progression of elevation/scaption, usually working to get full motion somewhere around 10-12 weeks ideally. Start with external rotation in neutral (by your side), then work yourself up to 45 and 90 degrees of abduction respectively to avoid anterior capsule stress. You are respecting when you would load those tissues that have been repaired. Begin rotator cuff activation, not strengthening, as early as possible. You also want to start scapular stabilizer muscle activation and rhythmic stabilization as early as possible.

The intent of the protocol below is to provide a guideline for the clinician, therapist, and rock climber following an arthroscopic anterior stabilization procedure. The author takes no responsibility and assumes no liability for improper use of this guideline. Individual patient values, expectations, preferences, and goals should be used in conjunction with this guideline.

In summary, respect and protect the appropriate tissues post-operatively. Progression of strength training and proprioceptive/dynamic stability should be based on performance criteria, not the times listed below. These time frames are just examples and are adjusted based on clinical criteria. It doesn’t matter how long it takes to get the strength back. It could be anywhere from 3 to 8 months, depending on various factors. Additionally, endurance and neuromuscular control are equally important as strength. The end stage of rehabilitation must be individualized to the functional tasks and demands of a rock climber.

Arthroscopic Anterior Stabilization Post-Op Guidelines

Protective or Acute Phase: Immediate Post-surgical (Week 1 – 3)

Goals:

- Respect and protect healing tissues

- Diminish pain and inflammation

- Initiate para-scapular muscle training/activation

- Initiate early Range of Motion (ROM)

Precautions:

- Always remain in sling, only removing for showering, physical therapy, and elbow/wrist ROM

- Avoidance of abduction and external rotation to prevent anterior capsule stress

- No lifting objects with operative shoulder

Week 1-2

Unload exercises:

- Wear sling at all times except where indicated above (Includes sleeping)

- Ice/cryotherapy

Mobility exercises (3 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 15-20 reps):

Week 3

Unload exercises:

- Continue use of sling

Mobility exercises (3 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 15-20 reps):

Protective Phase: PROM/AAROM (Weeks 4 & 5)

Goals:

- Gradually restore PROM of shoulder

- Do not overstress healing tissue

Precautions:

- No shoulder lifting or AROM

Week 4 & 5

Unload exercises:

- Continue use of sling

- May come out of sling at home and seated or in very controlled environment

Mobility exercises (3 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 15-20 reps):

- Circular Shoulder Pendulum with Support

- AAROM Shoulder Flexion

- Standing AAROM Shoulder Abduction with Dowel (up to 90°)

- Supine AAROM Shoulder External Rotation in 0° Abduction (up to 20°)

Strength exercises:

- Standing or Seated Scapular Retraction with Depression (5 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 5 reps)

- Pain-free Submaximal (10-20%) Shoulder Isometrics in Neutral (1 x daily – 5 x weekly – 2 sets – 10 reps w/ 5 sec. hold)

Sub-acute / Intermediate Phase (Week 6 & 7)

Goals:

- Initiate neuromuscular/proprioceptive/dynamic stability training ASAP

- Gradually increase external rotation ROM

- Progressive strengthening

- rotator cuff, scapular muscles, trunk, and legs

- Emphasis on muscular endurance

Precautions:

- Wean from sling

- No lifting with affected arm

Week 6 & 7

Unload exercises:

- May wean from sling, except in crowds, slippery surfaces, etc

Mobility exercises:

- Begin posterior capsular stretching (2 x daily – 6-7 x weekly – 3 sets – 30 sec.)

- AAROM Shoulder Flexion (3 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 15-20 reps)

- AAROM Shoulder External Rotation (3 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 15-20 reps)

Strength/Activation Exercises:

- Begin AROM in all planes (3 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 15-20 reps)

- Sidelying AROM Shoulder Flexion (full range)

- Progress AROM in gravity resisted positions

- Scapular stabilizer muscle activation (5 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 5 reps)

- Standing Scapular Retraction/Depression (w/ 5 sec. hold)

- Standing Scapular Clocks

- Submaximal (10-20%) Shoulder Isometrics in Neutral (1 x daily – 5 x weekly – 2 sets – 10 reps w/ 5 sec. hold)

- Flexion, extension, abduction (Continue from Week 4 & 5)

- External Rotation

- No internal rotation

- Rhythmic Stabilization (1 x daily – 4 x weekly – 3 sets – 20 sec.)

Strengthening Phase (Week 8 – 12)

Goals:

- Continue to enhance and normalize muscular strength, endurance, and stability

- Full AROM at 12 weeks

- Continue to gradually increase external rotation passively

- Enhance muscular strength, endurance, and stability

Precautions:

- No overhead strengthening

- Avoid extension and abduction until 12 weeks to minimize stress on the anterior capsule

Week 8-11

Mobility exercises:

- Continue to progress with non-painful AROM/AAROM

- See previous examples above

- Standing AAROM Shoulder Flexion Wall Walk

- Standing AAROM Shoulder Abduction Wall Walk

- Continue to increase External Rotation AAROM gradually

- Up to 65° at 20° abduction (see previous videos and increase range of motion)

- Up to 75° at 90° abduction (see previous videos and increase range of motion)

- Continue posterior capsule and pectoralis stretching

Strength Exercises:

- Scapular Stabilizer Muscle Activation

- Standing Scapular Retraction with Depression (5 x daily – 7 x weekly – 5 reps – 5 sec. hold)

- Scapular Clocks (2 x daily – 7 x weekly – 1 set – 10 reps)

- Rotator Cuff Muscle Activation (3 x daily – 6-7 x weekly – 15-20 reps)

- Standing Submaximal (10-20%) Isometric Shoulder External Rotation at Wall (in neutral)

- Standing Submaximal (10-20%) Isometric Shoulder Internal Rotation at Wall (in neutral)

- Shoulder External Rotation Resistance Band “Walk-Outs” or Reactive Isometrics

- Shoulder Internal Rotation Resistance Band “Walk-Outs” or Reactive Isometrics

- Progress to Resistive Exercises in Standing with Light Resistance Band (3 x daily – 4-5 x weekly – 15 reps)

- Standing Shoulder Flexion

- Standing External Rotation (in neutral)

- Standing Internal Rotation (in neutral)

- Add Oscillations to External and Internal Rotation for Rhythmic Stabilization

- Rhythmic Stabilization (1 x daily – 4 x weekly – 3 sets – 20 sec.)

Return to activity phase / Advanced Stage (Week 12 – 20)

Goals:

- Gradual return to strenuous work, recreational, and sports activities

- No climbing until 4 months post-op

Week 12-16

Mobility exercises:

- Maintain full non-painful AAROM and AROM

- See previous examples above

- Standing Shoulder Abduction Wall Walks

Strength Exercises:

- Standing Banded Resistive Exercises with Moderate Resistance Band (1 x daily – 4-5 x weekly – 2-3 sets – 15 reps)

- Forward Flexion

- External Rotation in Neutral

- Progress to 90° of Flexion (protected position)

- Add Oscillations for Rhythmic Stabilization

- Progress to 90° of Abduction (90°-90° position)

- Progress to 90° of Flexion (protected position)

- Add Oscillations for Rhythmic Stabilization

- Parascapular and Rotator Cuff Resistive Exercise (1 x daily – 4-5 x weekly – 2-3 sets – 15 reps)

- Sidelying External Rotation

- Progress to 2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- Shoulder Horizontal Abduction with External Rotation

- Standing with Resistance Band or

- Prone AKA “Prone T”

- Progress to 2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- Shoulder Scaption with External Rotation

- Standing with Resistance Band or

- Prone AKA “Prone Y”

- Progress to 2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- High Row into Shoulder External Rotation

- Standing with Resistance Band or

- Prone

- Progress to 2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- Sidelying External Rotation

- Body Weight Exercises

- Wall Push Up –> Inclined Push Up (1 x daily – 4-5 x weekly – 3 sets – 10 reps)

- Plank Hold Variations (1 x daily – 4-5 x weekly – 3 sets – 20-60 sec.)

- Rhythmic Stabilization (Begin Week 13, 1 x daily – 4 x weekly – 3 sets – 20 sec.)

- Sidelying External Rotation “Drop-Catch” with Mini Plyo-Ball

- Prone Horizontal Abduction “Drop-Catch” with Mini Plyo-Ball

- Mini Plyo-Ball Dribble at Wall Variations:

Week 16-20

Mobility Exercises:

- Continue Flexibility/ROM exercises

Strength Exercises:

- Foundational (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 2-3 sets – 12-15 reps)

- Shoulder Scaption with External Rotation

- Standing with Resistance Band

- Prone AKA Prone Y with 2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- Shoulder External Rotation in 90° Abduction Hold (3 sets x 30 sec.)

- High Row to External Rotation to Overhead Reach

- Standing with Resistance

- Prone

- Progress to 2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- Serratus Slides at Wall with Foam Roller

- Progress with Light Resistance Band at Wrists

- Shoulder Scaption with External Rotation

- Functional Rehab

- Seated High Lat Pull Downs (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 5 sets – 5 reps)

- start w/ low weight, ~40-60 lbs.

- Single Arm Lat Pull Down (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 2 sets – 12-15 reps)

- start w/ low weight, ~20-40 lbs.

- Half-Kneeling Single Arm Shoulder Overhead Press in Flexion (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 5 sets – 5 reps)

- Push Ups (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 5 sets – 5 reps)

- Plank Variations (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 3 sets – 30-60 sec.)

- Front Plank with Reach Combination

- Progress with Light Weights

- Front Plank Lateral Crawling with Resistance Band

- Front Plank into Shoulder External Rotation

- Front Plank Walk Over on BOSU Ball

- Slider Front Plank Walk

- Side Plank

- Progress with rotation and resistance (8-12 reps)

- ~2.5 – 15 lb. weights

- Progress with rotation and resistance (8-12 reps)

- Front Plank with Reach Combination

- Turkish Getup Phase I (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 3 sets – 8-12 reps)

- Half-Kneeling Bottoms Up Kettlebell Arnold Press (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 3 sets – 8-12 reps)

- Half-Kneeling Bottoms Up Kettlebell Shoulder Horizontal Abduction (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 3 sets – 8-12 reps)

- Seated High Lat Pull Downs (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 5 sets – 5 reps)

- Rhythmic Stabilization (1 x daily – 4 x weekly – 3 sets – 20-30 sec.)

Movement exercises:

- Dead Hang Isometric Hold on Overhead Bar (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 3 sets – 5-10 sec.)

- Assisted Pull-Ups (1 x daily – 3 x weekly – 3 sets – 10 reps)

- Starting with at least 25% of body weight unweighted

Return to Sport/Rock Climbing (Week 20 – Week 24)

- Return to rock climbing with approval from physical therapist or orthopedic doctor

- Start at low grade (i.e. 5.7-5.8)

- Add 25% more difficulty/volume every 2 weeks

- Basic Return to Play Criteria

- Full pain free range of motion

- No pain with resistive testing

- Symmetrical total range of motion

- Negative joint screen/special testing

- Functional testing of your choice

- Strong supraspinatus, PER, and external rotation at the side

- ER > 70% of IR

The Research

Generally speaking, the redislocation rate after initial dislocation is around 90% or greater. A surgical consult is encouraged if you are less than 35 years old, active or looking to go back to sports and activities, suspect a Bankart lesion following a dislocation or subluxation, and are positive on the Anterior Apprehension Test. ABR is currently the most performed treatment for anterior shoulder instability.3,4 Arthroscopic stabilization procedure for athletes without significant bone loss improves return to play rates and decreases recurrent instability.6 Conservatively managed adolescents of traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations have shown poor outcomes.7 Redislocation rates for shoulder instability after arthroscopic repair trend lower at < 20% in most studies. A small percentage of patients who have undergone this procedure go on to have recurrent instability.12,13 Additionally, ABR allows for a high rate of return to sport, with Memon et al10 finding 81% of patients returned to sport postoperatively. However, approximately 1/3 of the athletes in this systematic review did not return to their preinjury level of sport. One systematic review and meta-analysis11 looked at the current evidence comparing ABR versus nonoperative management of patients with first-time shoulder dislocation. This study found the rate of recurrence was 7 times lower than conservative management. Additionally, a significantly higher rate of return to sport was found after ABR. Therefore, ABR is recommended to perform routinely in patients with first-time dislocation who participate in sports to allow for both return to sport and a lower risk of recurrence.

The American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists (ASSET) developed the first consensus guideline for the rehabilitation of patients following ABR.5 However, current evidence for best rehabilitation practices after ABR is lacking. This has led to considerable variability in physical therapy protocols following ABR despite published consensus protocols. While generalized components of protocols are similar, there is not a widely accepted standard of care after surgery. Furthermore, it may be difficult to follow a consensus rehabilitation protocol because of differences in surgeon preference, surgical procedure, strength of suture anchor-bone construct, injury pattern, severity of the lesion, and patient factors.

A systematic review by Ciccottie et al8 identified 7 different categories in the literature used as criteria to determine when patients are ready to return to play following ABR. Those categories were time from surgery, strength, range of motion, and proprioceptive control. The current standard time frame for returning to play is 6 months. An important aspect of return to play for climbers and competitive athletes is functional rehabilitation centered on restoration of proprioceptive feedback of the shoulder joint after injury. A 2021 case series9 required athletes to successfully complete a functional testing protocol paired with a psychological assessment before they were allowed to return to play. This study demonstrated a significantly lower redislocation rate of 6.5% than what is currently published in most studies for this patient population.

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

The length and quality of physical therapy following an arthroscopic anterior stabilization plays an important role in the achievement of functional stability and your return to rock climbing. The therapy protocol proposed in this article by no means is intended to be a substitute for patient care after surgery. A physical therapist will use their expertise and evidence-based care to help you successfully return to climbing. Furthermore, if you need assistance with diagnosis or conservative and post-operative treatment for shoulder instability, please consult with a physical therapist or other medical professional. A physical therapist will develop an individualized, fine-tuned treatment program which will allow you to get back to climbing to your fullest potential. Using manual therapy, appropriate exercise, and evidence-based treatments, physical therapy will improve your climbing function and help you reach your climbing goals.

About the Author

Josh Jones graduated from the University of Colorado PT Program in 2022. In 2010, he was introduced to physical therapy as a rock climber, attempting to self-diagnose and self-treat medial epicondylalgia. He also had arthroscopic anterior stabilization of the shoulder 4 months before starting PT school. Through the rehabilitation process, he got back to climbing to his fullest potential and experienced first-hand how physical therapy can change lives.

Josh has been climbing for 15+ years, predominantly sport. His favorite places to climb are Rodellar, Spain; Ten Sleep Canyon; and Shelf Road just to name a few. Outside of working as a physical therapist and climbing, he enjoys salsa and bachata dancing, traveling, slacklining, yoga, meditation, live music, spending time with friends and family, and giving back to community through volunteer work and activism.

References

- Jobe FW, Pink M. Classification and treatment of shoulder dysfunction in the overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993 Aug;18(2):427-32. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.427. PMID: 8364598.

- Bacilla P, Field LD, Savoie FH. Arthroscopic Bankart repair in a high demand patient population. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:51-60.

- Glazebrook H, Miller B, Wong I. Anterior Shoulder Instability: A Systematic Review of the Quality and Quantity of the Current Literature for Surgical Treatment. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 Nov 16;6(11):2325967118805983. doi: 10.1177/2325967118805983. PMID: 30480013; PMCID: PMC6243418.

- Owens BD, Harrast JJ, Hurwitz SR, Thompson TL, Wolf JM. Surgical trends in Bankart repair: an analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery certification examination. Am J Sports Med. 2011 Sep;39(9):1865-9. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406869. Epub 2011 May 31. PMID: 21628637.

- Gaunt BW, Shaffer MA, Sauers EL, Michener LA, McCluskey GM, Thigpen C; American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists. The American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists’ consensus rehabilitation guideline for arthroscopic anterior capsulolabral repair of the shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010 Mar;40(3):155-68. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3186. PMID: 20195022.

- Donohue MA, Owens BD, Dickens JF. Return to Play Following Anterior Shoulder Dislocation and Stabilization Surgery. Clin Sports Med. 2016 Oct;35(4):545-61. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2016.05.002. Epub 2016 Jul 9. PMID: 27543398.

- Kelley TD, Clegg S, Rodenhouse P, Hinz J, Busconi BD. Functional Rehabilitation and Return to Play After Arthroscopic Surgical Stabilization for Anterior Shoulder Instability. Sports Health. 2021 Dec 17:19417381211062852. doi: 10.1177/19417381211062852. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34918564.

- Ciccotti, MC, Syed, U, Hoffman, R, Abboud, JA, Ciccotti, MG, Freedman, KB. Return to play criteria following surgical stabilization for traumatic anterior shoulder instability: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:903-913.

- Kelley TD, Clegg S, Rodenhouse P, Hinz J, Busconi BD. Functional Rehabilitation and Return to Play After Arthroscopic Surgical Stabilization for Anterior Shoulder Instability. Sports Health. 2021 Dec 17:19417381211062852. doi: 10.1177/19417381211062852. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34918564.

- Memon M, Kay J, Cadet ER, Shahsavar S, Simunovic N, Ayeni OR. Return to sport following arthroscopic Bankart repair: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Jul;27(7):1342-1347. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.02.044. Epub 2018 Apr 2. PMID: 29622461.

- Hurley ET, Manjunath AK, Bloom DA, Pauzenberger L, Mullett H, Alaia MJ, Strauss EJ. Arthroscopic Bankart Repair Versus Conservative Management for First-Time Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2020 Sep;36(9):2526-2532. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.04.046. Epub 2020 May 8. PMID: 32389771.

- Arciero RA, Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, McBride JT. Arthroscopic Bankart repair versus nonoperative treatment for acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1994 Sep-Oct;22(5):589-94. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200504. PMID: 7810780.

- De Carli A, Vadalà AP, Lanzetti R, Lupariello D, Gaj E, Ottaviani G, Patel BH, Lu Y, Ferretti A. Early surgical treatment of first-time anterior glenohumeral dislocation in a young, active population is superior to conservative management at long-term follow-up. Int Orthop. 2019 Dec;43(12):2799-2805. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04382-2. Epub 2019 Aug 7. PMID: 31392495.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.