Core is Back

My training plan used to look something like a form of aerobic warm up, climb as hard as I could with a little climbing skill practice sprinkled in and finish with an ab and pull up workout until I was completely gassed and groaning on the ground from muscle pain. Thanks to my no longer sixteen-year-old body, I have since learned differently. Recent literature suggests that a differentiated approach may result in improved adaptation for climbing. This raises the questions: How much abdominal training is necessary to improve climbing and what components are best focused on? Let’s cast a broader scope past the abdominals to all the muscles that make up the core or trunk of our body.

Anatomy and Function

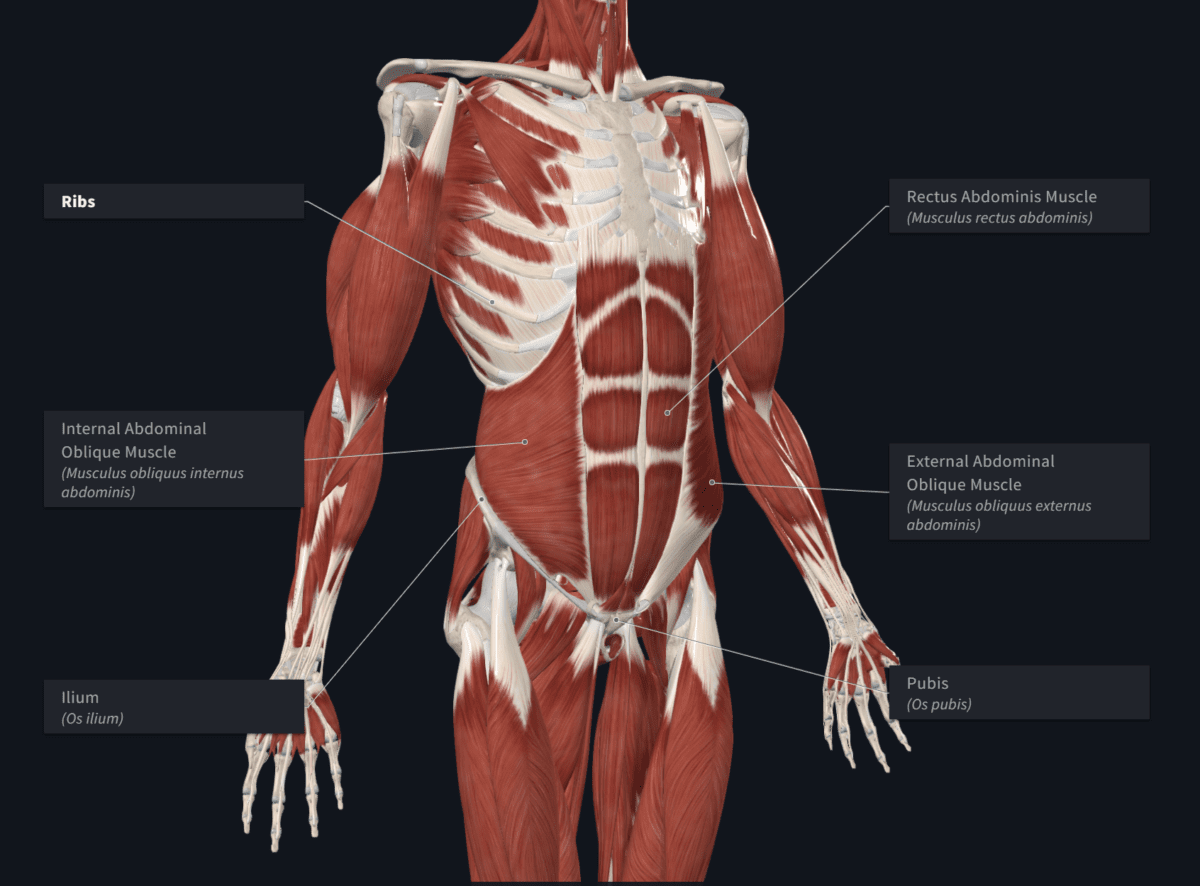

Before I can answer my research question, I think many climbers have some misconceptions about what abdominals and their functions are. I used to believe my abs were the muscles that gave me a six pack and helped me do crunches. However, this does not paint the full picture, so let’s take a look.

What do the abdominal muscles connect to? Our ribs, hip bones, and spinal column create a cylinder of sorts.

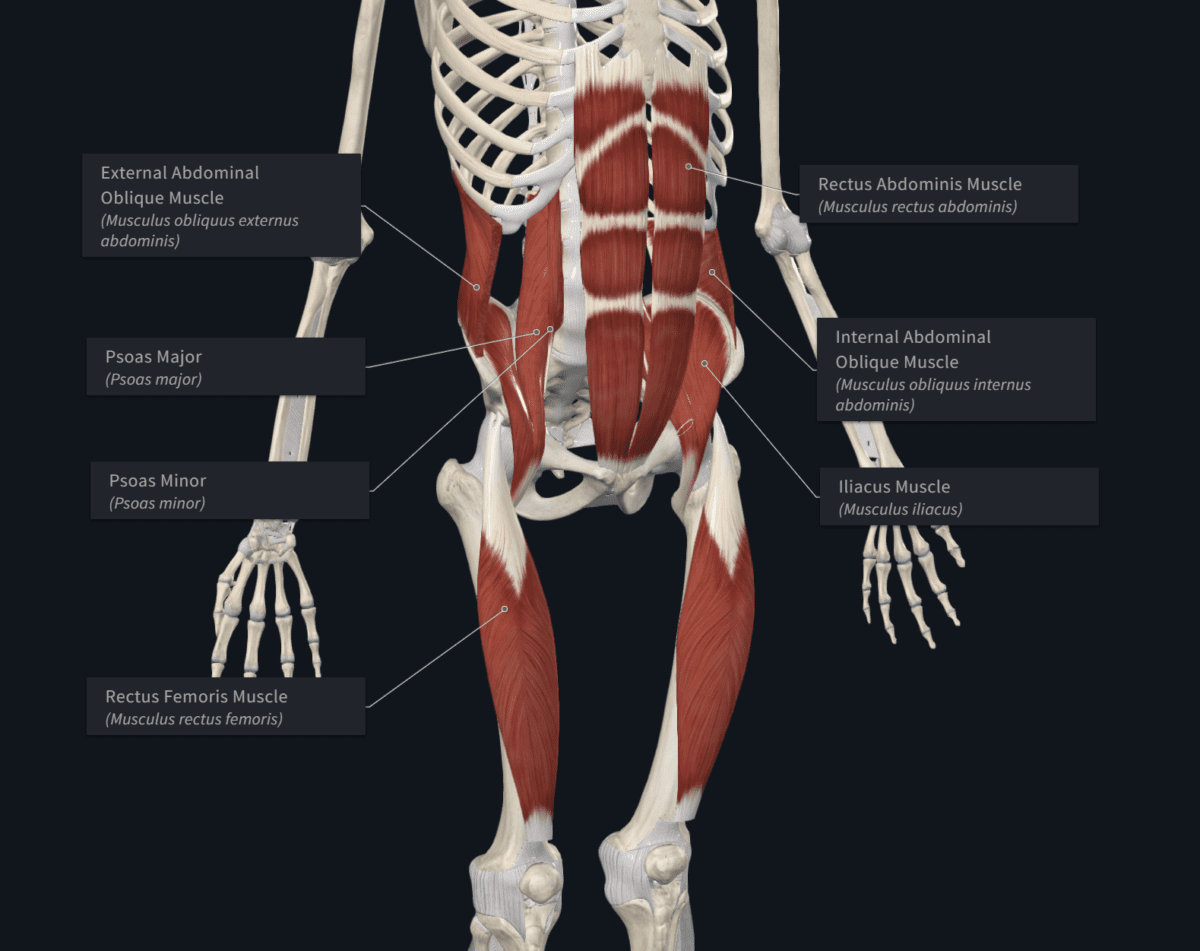

Figure 1. Core structures (Complete Anatomy)

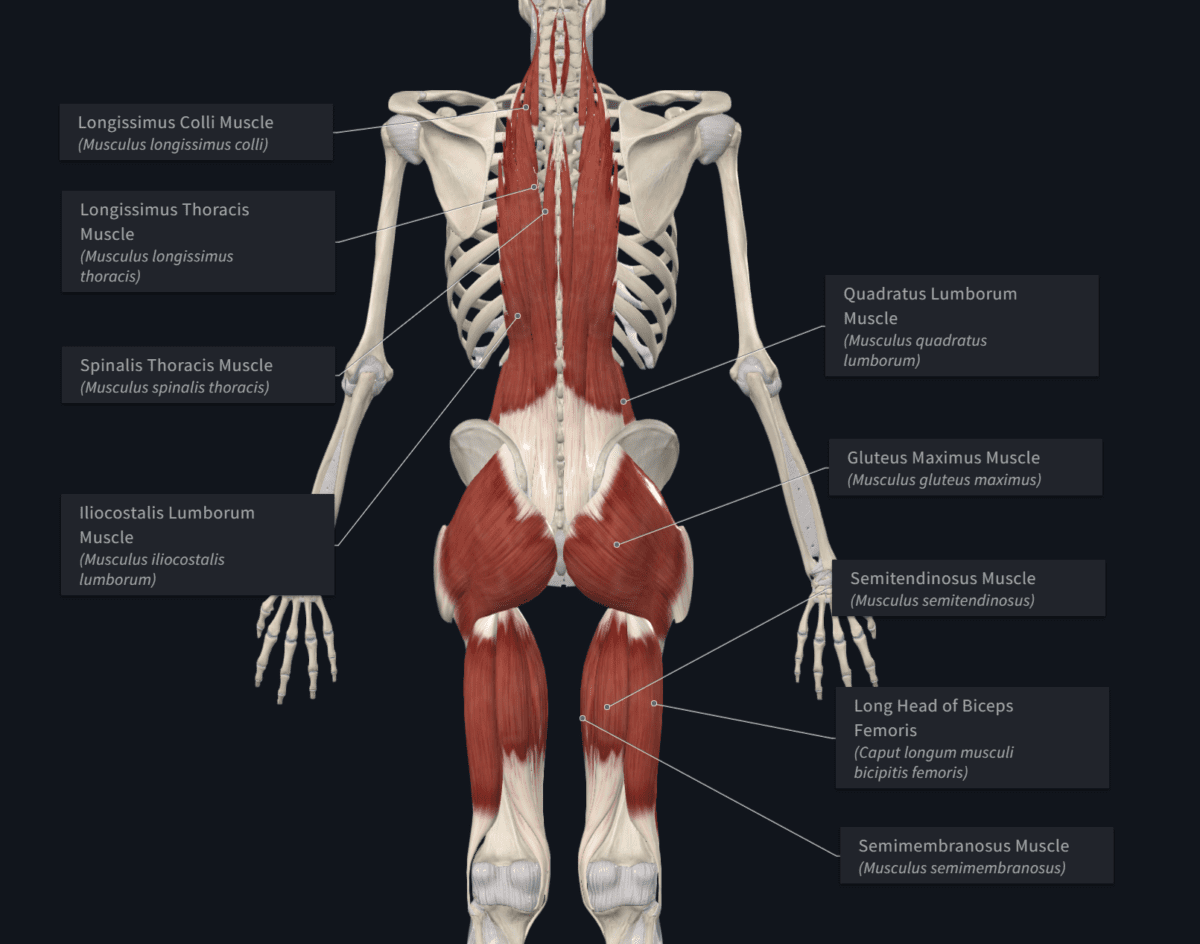

As can be seen in Fig. 1-3 the abdominals make up the entire circumference of our midsection, allowing us to stand, sit and bend. There are also muscles that form a roof and floor to this cylinder creating the anatomical box.

These muscles can be broken into five main categories:

| Trunk Flexors | Trunk Extension | Lateral Flexion | Trunk Rotators | Respiratory | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Bending the trunk and raising thigh to chest. | Extends the back, drives hips forwards and pulls thighs back. | Rotation of the trunk left or right | Rotates trunk left or right. | Aids with breathing and increasing stiffness of the trunk. |

| Anatomical Location | Ribs to thigh | Neck to knee | Ribs to pelvis | Ribs to pelvis | Clavicle to 12th rib |

| Muscle 1 | Rectus abdominis | Deep and superficial erector muscle groups | Internal oblique | Internal oblique | Diaphragm |

| Muscle 2 | Internal obliques | Quadratus lumborum | External oblique | External oblique | Inner intercostal |

| Muscle 3 | External obliques | Gluteus maximus | Quadratus lumborum | External intercostal | |

| Muscle 4 | Psoas group | Hamstrings | Gluteus maximus | Pectoralis minor | |

| Muscle 5 | Iliacus | Medius | Serratus posterior inferior | ||

| Muscle 6 | Rectus femoris | Minimus |

Figure 2. Trunk flexor muscle group (Complete Anatomy)

Figure 3. Trunk extensor muscle group (Complete Anatomy)

How effective is core training for increasing climbing performance?

Our core muscles receive stimulus everytime we climb, meaning they are getting stronger as we go about climbing. However, that might not be enough for them to keep pace with the strengthening of other muscle groups predominantly used in climbing, like finger flexors and biceps. This may be particularly true in movements that require peak strength or high rate of power production. Taking a step back, how impact does abdominal training really have on our performance in climbing?

If we look at two recent studies about core training and climbing, one study focused on what exercise correlated the most with climbing higher grades. The findings list shoulder power and endurance first, and core-body endurance as only the fifth most correlating exercise to climbing[1]. The second study compares the transfer of core strength from isometric and dynamic core training. The comparison was done over ten weeks to determine the effectiveness in improving the results in specific climbing tests. The study found only isometric exercises to have an effect, however the dynamic group was the only one to improve in rotational movements [2].

Looking outside of climbing to a multitude of sports, to address the question, whether core training helped participating athletes improve in their respective sports, a review examined eleven different sports, including football (soccer), handball, basketball and gymnastics. It concluded that core training can have an effect, and should be integrated into training plans [3]. Another study concluded that core training had great effect on core endurance and balance in athletes, however it had little effect on sport specific performance. It recommended that core training should be modified to be as sport specific as possible [4].

Supplementing what we know about climbing with research literature, we can conclude that most climbers have a sufficient level of core endurance without the need of additional core training. In climbing, however, we need to be able to generate high levels of power and strength, our core muscles do not receive consistent enough stimulation to make the gains required for these peak efforts. Therefore, when core training is performed, it should focus on specific exercises to increase power and strength. To determine if our core is strong and active enough, keep reading.

How do we test our core for strength?

In most climbing moves, the main action of our core is extension, preventing our hips from swinging out, taking our feet with them; however if we intend to swing when jumping (dynoing), for example, then we must return our feet to the wall, which requires flexion of our trunk. Rotation of our trunk is also a constant in climbing, allowing us to reach holds farther away and put us in advantageous positions for difficult holds. This requires us to test multiple functions to get a complete picture of our core’s strength. For some it may be sufficient, while others may need training. For non-climbing specific core strength testing there are three tests that can easily be used:

-

Trunk Extension: Biering-Sorenson Test [5]

-

- Bench or table needed.

- Lie down on the bench or table facing the floor.

- Align your hip joint with the edge of the table.

- Have someone sit on or hold down your legs. to the table. The weight has to be sufficient, so that you can extend your back to be horizontal with the table without support and without tipping forwards.

- Arms crossed under chest.

- Test is terminated if your trunk starts to sag downward or if self-terminated.

- Sufficient time is 2 minutes 22 seconds.

(Nota bene: this test is validated for people with low back pain. For healthy, active, young adults this test needs to be modified (increased in difficulty) to be effective. Increase the difficulty by adding weight and possibly reducing time down to 1 minute.)

-

Trunk flexion rotation test: [5,6]

-

- Lie on the floor face up.

- With feet flat on the floor bend knees to 90 degrees keeping them together.

- Lie with head and shoulders on the floor. Have a friend sit by your feet placing weight on your feet with their legs. They place each hand as a fist on either side of your knees and press in.

- Interlock thumbs with outstretched fingers. In 90 seconds perform as many curling rotation motions as possible, where your fingertips tap the outside of your friend’s fist.

- A sufficient score is over 90 reps.

-

Core stability test: unilateral hip-bridge endurance test (UHBE) [7]

-

- Lie down on your back on an even surface.

- Put both feet on the ground, arms crossed on your chest.

- Push up with both feet into a bridge position until knees to shoulders build a straight line.

- Then lift one leg and extend at the knee until it is in line with your hips and shoulders.

- Hold as long as possible.

- Test terminates when either one side of your hip starts to dip or your butt starts to sag towards the floor.

- Sufficient time is more than 23 seconds.

These tests, while having a set methodology that has been validated, are fairly general and are not well suited for sport specific strength and power testing [5, 8]. In terms of climbing they are best suited to test our core endurance. One thing all of these articles discuss in their conclusions, is that for core testing to be valid, it needs to be as specific to the movement demands as possible. The core is an enabler of our limbs, offering support or transferring kinetic energy from one extremity to the other. For testing we have three main components to consider: endurance, strength and power.

An indication that we are lacking endurance would be feet becoming sloppy or popping off at some point during our climbing session, when at the start of our training session that had not been an issue. If this is the case, we should prioritize recovery. When our feet start slipping off we have reached momentary failure. We rest, and if performance is not recovered after 3-5 minutes, then we are fatigued. Leaving the gym, eating something and getting some sleep is our best bet.

Power production is more difficult to test and yet it is probably the component that needs occasional training. This is for our dynos and extreme tension moves, where a well-timed, high rate of force contraction is needed. The reason we can fail on these moves is three-fold, however, thus providing some challenges for testing. First and most simply, are we strong enough? This will be the main focus of our testing. Next is timing and neuromuscular coordination. Do our muscles contract at the right time in our dyno swing to bring our feet back into the wall? Has our nervous system learned that when our feet are off the wall, our abdominals have to contract really hard and fast to counter that inertia? The good thing about our nervous system is that in this regard, it can adapt quickly and is often responsible for our rapid progress in the beginning. While there are no currently validated tests for measuring power production, the four tests below are my suggestions based on the research and my experience as a coach and physical therapy student. Last but not least, is technique. Are we driving enough through our feet, how is our weight distributed, etc… This is best assessed with video analysis and a coach.

The following four tests will help determine if your core is a limiting factor:

Note: these following tests are complex and therefore will have a learning effect if we have not performed these moves often and/or over a prolonged period of time. For climbers newer to these types of movements, there will be rapid progression from test to test (this is a good thing). However, this will be due to neuro-musculature adapting to these specific loads and timings, and will not only be an expression of an increase of strength, as gained through consistent training.

-

Wall Kick-ons (from Gimme Kraft)

- Resources needed:

- Overhanging climbing wall.

- Instructions:

- Choose two good starting hand holds (relative to your climbing ability) that can be reached standing on the ground. The smaller the hold the less surface area you will have to hold your body tension.

- Choose one or two foot holds that will be your target. The foot holds should be relatively difficult or equal to foot holds on your current max projects or redpoints.

- You will swing into the wall and land your foot or feet on the target hold/s and maintain that tension for 3 seconds. For added difficulty, if done with only one foot, repeat with the opposite foot.

- Results:

- If you are able to match in distance between hand and foot holds, and difficulty of foot holds that are on your project where you have been falling off, then probably your core is not a great limiting factor and fingers or shoulders should be your focus.

- However, if you can’t get your feet to stay on the wall or if you feel like your back just peels away, then strength training may help.

- Resources needed:

-

Max Reach

- Resources needed:

- Spray wall or densely set wall, ideally at least a few degrees of overhang.

- Instructions:

- Choose two foot holds that are similar to your current red point boulders routes.

- Find hand holds similar to the better hand holds on your red point climbs, about shoulder height from the chosen foot holds.

Get on the wall and hold for a few seconds to make sure feet are well placed. - Proceed to gradually move your hands higher on fairly good holds until your feet pop off or you are unable to hold the tension, causing your butt to pull you off.

- You can measure this distance to have a reference of improvement if you retest some time later.

- Results:

- If you are able to achieve a similar distance during this test as your current red points, then techniques or other strength factors outside your core are causing you to fall off the wall.

- Resources needed:

-

Swing outs

- Resources Needed:

- Overhanging climbing wall.

- Instructions:

- Choose two hand holds that are slightly better than the average hold on your red-point or project.

- Choose a size foot hold commonly found in your climbing.

- Once established on the wall, kick off with your foot and let yourself swing out.

- Time your abdominal contraction to prevent popping off the hand holds and drive your feet back to the wall.

- Land your foot back on the hold it had just come off of and hold for a few seconds.

- Results:

- If your foot stayed on the hold on the first try, great! If you swung out again and had to dangle to get your foot back on, then it could mean two things. One you lack the force needed to get your feet back to the wall (abdominals). This means your feet probably didn’t even touch the holds. Otherwise it can be a timing or strength issue, where you were not able to produce the force at the right moment to keep your feet on (back and hip extensors).

- Resources Needed:

-

High Step

- Resources needed:

- Finger or campus board.

- Instructions:

- Select hand holds that are good relative to your strength. Your fingers must easily be able to hold your weight for 15-20 seconds

- Hang with feet off the ground and attempt to raise one foot as high as you can while keeping your knee completely bent and arms straight

- Bending the hip and trunk is allowed.

- Have a friend measure how high the bottom of your heel went. Repeat on the other side.

- Results:

- This tests your ability to flex your hip and side flex your trunk. Both sides should be fairly equal in height. Less than 3 centimeters (1,5 inches) difference is a negligible difference. If it’s more than that, consider working on the lower side. A good score is being able to reach opposite hip height with maximally bent knee and hip.

- Resources needed:

If wall kick ons and swing outs are a struggle, training our core flexion ability is our best bet. A thing to note with both these tests is that they also have a timing component. The moment our feet make contact with the wall, we have to change force from pulling in to extension driving pressure to our toes. Therefore, if our feet reach the wall easily, but struggle to weight them, then just practicing these moves to learn the timing can be crucial. Remember to start easy so the timing is less sensitive and then increase the difficulty. Muscles that should be targeted for training are pecs, triceps, rectus abdominis and obliques.

Two recommended exercises would be:

- Stir the pot [9]

- Curl up [9]

Max reach test is good for testing the posterior chain (erector spinae, lats, glutes, hamstring and calf muscles).

If in this exercise you could not match the distance you commonly find on your red-point climbs, then the following two exercise may help you in this regard:

- Deadlift [9]

- Hip Thrust [9]

- Unilateral Bent over row [9]

Lastly, the high step test is meant to determine how high you can pull your thigh with your rectus femoris and psoas muscles and how well you can shorten one side of your trunk using your quadratus lumborum, internal oblique and erector spinae.

Two exercises that can aid in this are:

- End range hip flexion with resistance

- Kime kettlebell swing [9]

These six exercises make up a complete training profile for the core musculature utilized in climbing. A general recommendation would be to split them up into two groups performed on different days of the week. Take one exercise from each grouping, for example, curl up, deadlift and end range hip flexion with resistance, and then perform the other three during a different session. As we want to focus on either power or strength, repetitions should stay low, between 5-8 and not exceed two sets. For power take a lower weight, around 60% of one repetition max and focus on powerful fast movement. If strength is our goal, choose a higher weight, 80% or more of one repetition max with a focus on slow consistent movement. A good way to progress is working up to eight repetitions with our chosen weight, then choose a new higher weight and go back down to 5 repetitions.

However if spending time in the gym’s weight room is not your jam, or you are a newer climber still building up your confidence and repertoire of climbing moves, then taking the above mentioned climbing tests and adding repetitions can turn them into great exercises.

References:

- MacKenzie R, Monaghan L, Masson RA, Werner AK, Caprez TS, Johnston L, et al. Physical and Physiological Determinants of Rock Climbing. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020 Feb 1;15(2):168–79.

- Saeterbakken AH, Loken E, Scott S, Hermans E, Vereide VA, Andersen V. Effects of ten weeks dynamic or isometric core training on climbing performance among highly trained climbers. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0203766.

- Luo S, Soh KG, Soh KL, Sun H, Nasiruddin NJM, Du C, et al. Effect of Core Training on Skill Performance Among Athletes: A Systematic Review. Front Physiol. 2022 Jun 6;13:915259.

- Dong K, Yu T, Chun B. Effects of Core Training on Sport-Specific Performance of Athletes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023 Feb 9;13(2):148.

- Juan-Recio C, López-Plaza D, Barbado Murillo D, García-Vaquero MP, Vera-García FJ. Reliability assessment and correlation analysis of 3 protocols to measure trunk muscle strength and endurance. J Sports Sci. 2018 Feb;36(4):357–64.

- Brotons-Gil E, García-Vaquero MP, Peco-González N, Vera-Garcia FJ. Flexion-Rotation Trunk Test to Assess Abdominal Muscle Endurance: Reliability, Learning Effect, and Sex Differences. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2013 Jun;27(6):1602.

- Butowicz CM, Ebaugh DD, Noehren B, Silfies SP. VALIDATION OF TWO CLINICAL MEASURES OF CORE STABILITY. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016 Feb;11(1):15–23.

- Zemková E. Strength and Power-Related Measures in Assessing Core Muscle Performance in Sport and Rehabilitation. Frontiers in Physiology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 13];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.861582

- Oliva-Lozano JM, Muyor JM. Core Muscle Activity During Physical Fitness Exercises: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 16;17(12):4306.

Author Bio:

Jonathan O’Connors is a Physical Therapy student at Avans University in the Netherlands (NL). He focuses on sport and pediatric rehabilitation. He has been climbing for the past ten years, and has worked as a PCIA certified guide in Acadia National Park, as an assistant coach at Ivy Climbing in Sittard NL and as an assistant climbing coach for the Climbing Academy.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.