Abdominal Strains In Rock Climbers

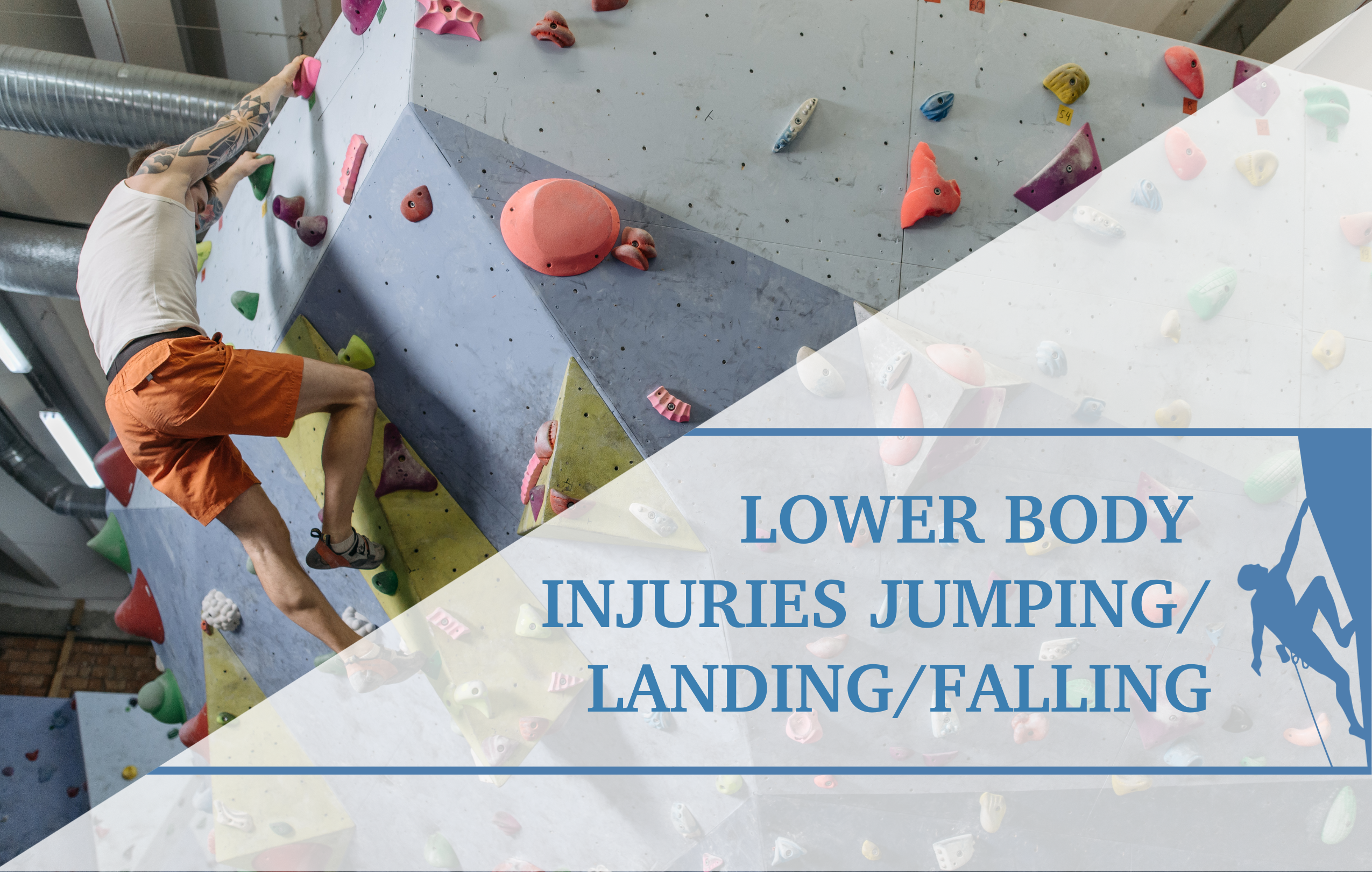

It’s been a busy week and you decide to go to your local climbing gym to practice some bouldering moves that you’d like to master. In particular, you want to dyno from one section of the wall to another. A “dyno” is a dynamic maneuver that requires a climber to jump off of the wall to grab another hold. After reaching the holds you are going to dyno from, you eye out the hold that is just out of reach without jumping. Lowering yourself into the wall to generate momentum, you explode off the wall towards the target hold above you. As you grab onto the desired hold, you feel a “popping” sensation in your abdomen accompanied with an immense pain forcing you to let go of the hold and fall back onto the mat. What has just happened?

Signs and Symptoms

What you may have just experienced is an abdominal strain. Activities that require repetitive trunk movements such as rotation, side bending, and extension, contribute to abdominal strains.

Rotation During Climbing

Sidebend During Climbing

Extension During Climbing

Image sources from left to right:

beta-angel.com/research/research-inventory/trunk/

theclimbingdoctor.com/hunchback/

beta-angel.com/research/syntheses/climbing-mobility-0/climbing-mobility-3/

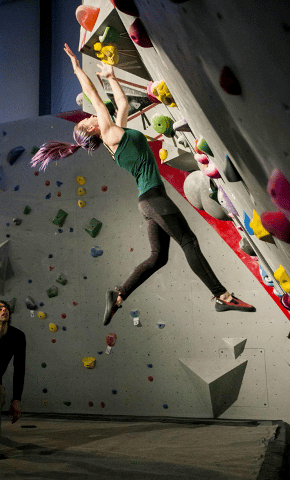

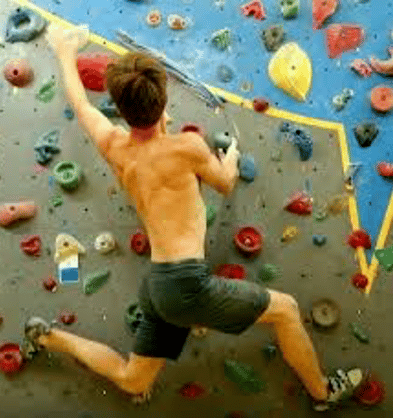

Muscle strains result from a sudden contracture of lengthened muscle fibers that causes them to rupture. In regard to climbing, abdominal strength, flexibility, and neuromuscular coordination is critical. Impaired abdominal function may result in injury when climbing considering the demand placed on the abdominals to stabilize a climber. For example, when performing a “dyno”, a climber will need to maintain trunk stability that follows grasping onto an overhanging hold.

Performing a Dyno

Twisting While Stemming

Image sources from left to right:

gripped.com/indoor-climbing/janja-garnbret-wins-fourth-straight-boulder-world-cup/ Photo credit Eddie Fowke IFSC

gripped.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Screen-Shot-2020-02-25-at-3.33.05-PM.png

Furthermore, any weaknesses or neuromuscular imbalances that a climber might have in their abdominals may go unnoticed and contribute to eventual injury and compensatory movement patterns. If a climber experiences an abdominal strain, it results in prolonged periods of discomfort, pain, and withdrawal from climbing activities until tissue repair occurs. If an abdominal strain is left untreated, reinjury may occur or contribute to secondary injuries to other tissues.

Abdominal strains have been reported in athletes who participate in repetitive activities such as baseball, golf, tennis, soccer, and football. However, the prevalence of abdominal strains in climbers in literature is limited. Given the important relationship the abdominals have in connecting and stabilizing the upper and lower extremities, climbers must be in tune with proper abdominal function to avoid injury and climb efficiently. This article will discuss the nature, assessment, and treatment of abdominal strains in relation to climbing. It will also include a rehabilitation guide utilizing Dr. Jared Vagy’s, “Rock Rehab Pyramid,” to achieve complete recovery of abdominal strains and aid in injury prevention.

Muscle strains result from a sudden contracture of lengthened muscle fibers that causes them to rupture. In regard to climbing, abdominal strength, flexibility, and neuromuscular coordination is critical. Impaired abdominal function may result in injury when climbing considering the demand placed on the abdominals to stabilize a climber. For example, when performing a “dyno”, a climber will need to maintain trunk stability that follows grasping onto an overhanging hold.

Assessment

Acute muscle strains result in sharp localized pain with either stretching or active contraction of the muscle fibers. Careful palpation, positioning, and examination of the abdominal wall muscles can identify the specific muscle and location of the strain. Once you have determined that you indeed have an abdominal strain, it must be classified into one of three grades.

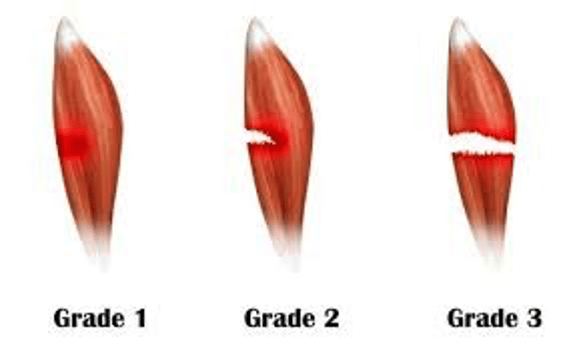

Muscles strains can be categorized into three categories based on severity.

• Grade I strains consist of stretching and micro tearing of the muscle fibers.

• Grade II strains indicate a partial tear of the muscle fibers.

• Grade III strains involve a complete tear or rupture of the muscle fibers.

Conservative treatment and Physical Therapy should focus on treatment of Grade I-II strains, Grade III strains require referral for medical attention.

Photo credit: epainassist.com/muscles-and-tendons/muscle-tear-types-treatment

Depending on the specific trunk movement, abdominal strains may occur within tissues of the rectus abdominis, internal oblique, external oblique, or transverse abdominis. It is crucial to closely examine the mechanism of injury to correctly diagnose the location of the abdominal strain. A good understanding of the anatomy of the abdominal wall is needed to assess and treat the strain.

Rectus abdominis strain: The vertical fibers of the rectus abdominis would be most likely involved in hyperextension type injuries. These can occur during powerful dynamic movements such as campus boarding and dynoing.

Campus Board

Dyno

Image sources from left to right

saltpumpclimbing.com/how_to_dyno

nicros.com/training/training-articles/reactive-training-part-5-campus-training-double-dynos/

Internal oblique or external oblique muscle strain: Rotational or side bending type injuries would indicate strains to the diagonal fibers of either the internal oblique or external oblique muscles.

Oblique Activity Example 1

Oblique Activity Example 2

Image sources from left to right

weclimbrocks.wordpress.com/tag/smith-rocks

zhuhan0.blogspot.com/2017/03/climbing-back-step.html

To differentiate between the obliques, the external obliques perform rotation to the opposite side whereas the internal obliques perform rotation to the same side. Overstretching pain and pain accompanied by muscle contraction of the particular oblique could help isolate the injured tissue. Transverse abdominis strains are rare, and it is actually weakness of this muscle which has been shown to be a contributing factor to abdominal strains. Strengthening of the transverse abdominis is a key component in the rehabilitation and injury prevention of abdominal strains.

Additionally, observation of the climber’s posture will help them identify potential weakness that may lead to abdominal strains. Postural control of the pelvis, spine, rib cage, and extremities, should be assessed in positions that mimic those that are evident during climbing. Examples of these positions include; squats, single limb squats, quadruped, and the bear crawl position. Deviations from neutral spine, pelvic, and rib alignment in any of these positions indicate weakness of the abdominals and require strengthening.

Neuromuscular coordination and control of the abdominals should be considered during assessment of the climber. An article by Hodges, et. Al. in 1999, revealed altered abdominal recruitment patterns were related to people with low back pain and arm movements at different speeds. People without lower back pain demonstrated “feedforward” activation of the transverse abdominis and internal obliques prior to intermediate or fast arm movements. In contrast, subjects with lower back pain did not contract the transverse abdominis or internal obliques prior to arm movements at the same speed. It is imperative for the climber to demonstrate adequate motor control, planning, and coordination of the abdominals not only to prevent injury but to climb more effectively.

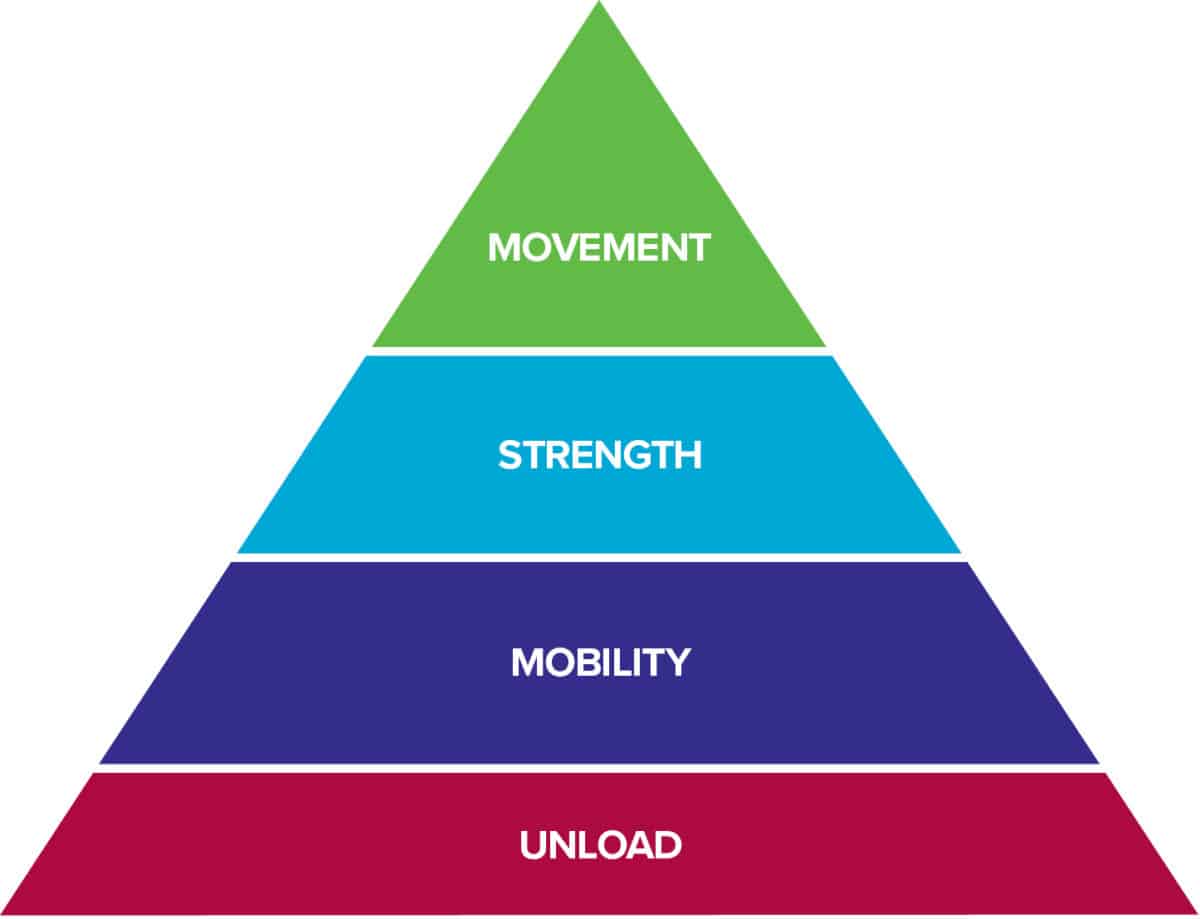

The Rock Rehab Pyramid

The Rock Rehab Pyramid was developed by Physical Therapist, Dr. Jared Vagy in his book Climb Injury-Free.. This pyramid aides in the rehabilitation of climbing injuries by providing a system of four major categories that will guide the climber’s recovery process. Following an injury, one will start at the bottom of the pyramid and work upwards using general guidelines to determine appropriateness for progression to the next level. A decrease in pain/soreness allows advancement to the next level. With no change in symptoms at a particular level, a climber should stay at the current level for one week and then progress to the next level. An increase in soreness should have the climber regress down one level.

The bottom level of the pyramid aims to decrease Pain, Inflammation and Tissue Overload so that the tissues have the best healing environment. Often times, after an injury there is some sort of change in Mobility. After the tissues have calmed down from the previous level, this stage will look to reestablish normal, pain free range of motion. Once the injured area restores its mobility, it is time to increase the Strength of the surrounding muscles so that Movement in the following level can be coordinated and optimized. Click here to learn more about the rock rehab pyramid structure.

Unloading Phase

Stage one occurs immediately after injury and focuses on limiting the amount of pain, inflammation, and tissue overload. In this stage it is important to limit the amount of the usage of the abdominals as it may contribute to further injury.

Step 1: Avoid any movements and activities that cause an increase in pain. If there is pain with static positions such as sitting or standing, an abdominal brace can be used.

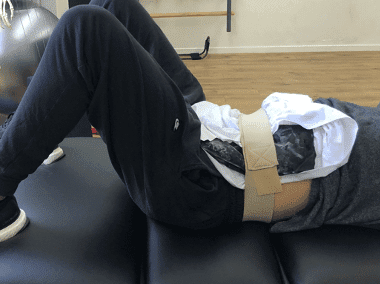

Step 2: Apply ice to the injury site for 15 minutes, 2-3x/day. Appropriate application of cryotherapy on the trunk includes adequate wrapping of the ice pack in a pillowcase or towel and compression wrapping.

Step 3: Self myofascial release using a therapy ball (sand or medicine ball) on trigger points along the abdominals. Perform for 1-2 min, 2-3x/day as tolerated. Since the abdominal area is a sensitive area near your digestive tract, make sure that you avoid causing an upset stomach or nausea while performing.

Mobility Phase

The mobility phase emphasizes achieving full functional trunk range of motion to avoid any adhesions or scar tissue build up within the abdominals.

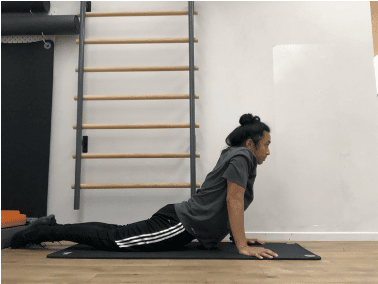

Cobra stretch:

Lying flat on the floor in the prone position, prop up onto your elbows or hands (whichever is more tolerable) until a stretch is felt in the abdominals. Hold stretch for 3 x 30 sec holds, 2-3x/day.

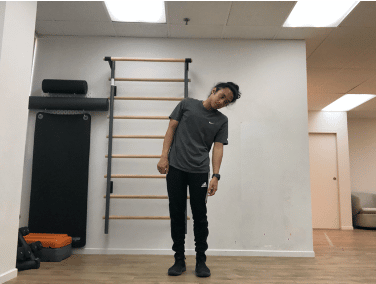

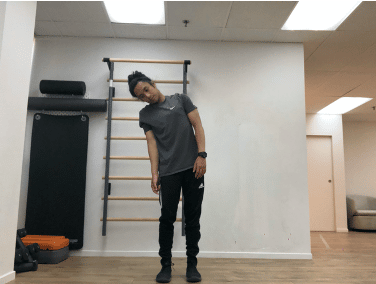

Side bend stretch:

Standing upright, bend your trunk to the side until a stretch is felt on the opposite side of the

bend. Perform this stretch to the left and right side. Hold stretch for 3 x 30 sec holds, 2-3x/day.

Start

Finish

Trunk Rotation Stretch:

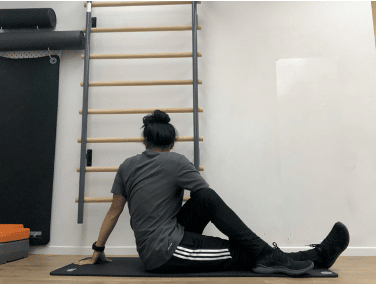

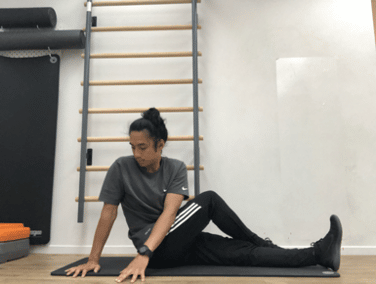

In the long sitting position, cross one leg over the other and bend the knee. Reach your arms across your body and behind you in the direction opposite of your bent knee. Perform this stretch towards the left and right side. Hold stretch for 3 x 30 sec holds, 2-3x/day.

Start

Finish

Strengthening Phase

The strengthening phase should emphasize appropriate motor recruitment sequencing to ensure adequate stabilization of the abdominals to avoid reinjury or development of faulty movements patterns. It is imperative to maintain neutral pelvis, spine and rib cage positioning. Also, the sequencing of muscle activation should be that of the transverse abdominis followed by that of the surrounding abdominal muscles prior to upper or lower limb movements. This will build and reinforce proper neuromuscular control for the climber in the rehabilitation process and hopefully carry over to climbing.

Abdominal bracing:

In a hook lying position, maintain neutral pelvis, lumbar spine, and ribcage. Tighten your stomach muscles and draw your navel towards your spine. Isolate the transverse abdominis by pressing your fingertips into your relaxed abdomen. When you tighten your abdomen, push your fingertips away from the center of your body. Hold for 5 sec x 10 repetitions.

Dead Bug:

Lying on your back with hips and knees bent to 90 degrees, maintain neutral pelvic tilt, lumbar spine, and ribcage. Activate the transverse abdominis and reach one arm overhead as the opposing leg straightens out without touching the floor. Do not allow the spine to arch during this movement. Return to starting position and repeat on the opposite side. Perform 3 x 10 repetitions. Bands may be used to increase resistance.

Bird dog:

In the quadruped position, maintain neutral pelvic tilt, lumbar spine, and ribcage. Activate the transverse abdominis and slowly raise a leg and the opposite arm upward. Lower the arm and leg and repeat with the opposite side. Maintain stable pelvis and spine throughout the exercise. Perform 3 x 10 repetitions. Bands may be used to increase resistance.

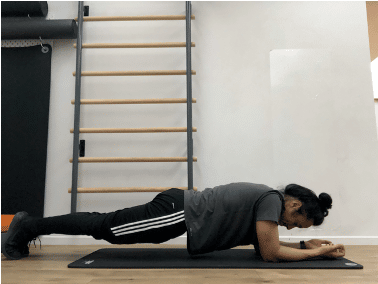

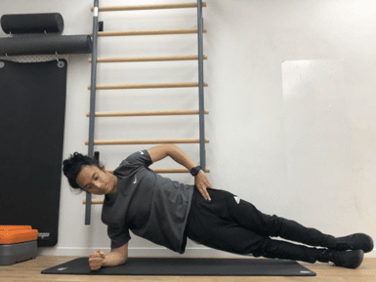

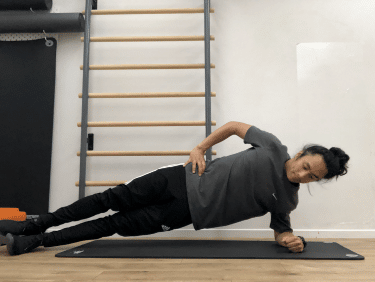

Planks/Side Planks:

Lying face down, lift your body up on your elbows and toes. Do not allow your hips or pelvis on either side to drop while maintaining neutral pelvis and spine. Hold for 30 seconds x 3 sets. Perform to each side, facing left then right.

Front Plank

Right Sideplank

Left Sideplank

Plank Sliders (Upper and Lower Extremities):

Starting in the plank position with both hands and feet in contact with the floor, place a slider under each foot and proceed to draw one knee towards your chest while maintaining the plank position. Return your bent knee to the starting position and repeat on the opposite leg. Perform alternating limbs 3 x 10 repetitions.

Repeat the same exercise with sliders under the hands reaching one arm out to the side while stabilizing your core and maintaining plank position. Return to the starting position and repeat on the opposite arm. Perform alternating limbs 3 x 10 repetitions.

Movement Phase

The final phase of movement is an application of the mobility and strength gained thus far into climbing specific tasks. Here the climber will reinforce proper movement patterns that will prevent future injury and promote a safer and more effective manner of climbing.

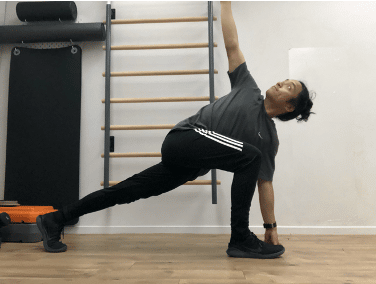

Low lunge and twist:

Perform a low lunge and reach for the floor with the opposing arm of the leading leg. Twist your trunk towards the leading leg and reach upwards with the arm. Perform on both sides. Perform for 2 x 15 repetitions.

Right Rotation

Left Rotation

Bear Crawl:

In the quadruped position, raise up onto your hands and feet. Maintain neutral pelvis and spine while your crawl forward 15-20 feet, return to the starting position by going backwards reversing the movement.

Hanging Hip Flexion and Extension:

A good climbing specific movement drill is to hang from a pullup bar and bring your knees to your chest and then behind you away from your trunk. Be sure to keep your trunk straight. This maneuver will strengthen your abdominals in a stretched position, something you may encounter during climbing. Perform 3×10 repetitions.

The Research

- Hodges PhD, Paul W., and Carolyn A. Richardson PhD. “Altered Trunk Muscle Recruitment in People With Low Back Pain With Upper Limb Movement at Different Speeds” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1999 Sep;80(9): 1005-12.

- Johnson, R. Abdominal wall injuries: Rectus abdominis strains, oblique strains, rectus sheath hematoma. Curr Sports Med Rep 5, 99–103 (2006) doi:10.1007/s11932-006-0038-8

- Vagy, Jared. Climb Injury-Free: A Proven Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation System. Climbing Doctor, 2017.

See a Medical Practitioner

Injuries, such as abdominal strains, that occur from climbing should not be taken lightly. If not correctly diagnosed and treated, an injury can potentially lead to more serious injuries, pain, and possible withdrawal from climbing completely. However, if correctly diagnosed and treated properly, a climber can recover from an injury and return to climbing pain-free. Seeing a medical practitioner that is aware of the rehabilitation process and well-versed in appropriate treatment techniques is highly beneficial. Whether you are an avid climber or a beginner, seeking treatment for any pain or injury you encounter is your best way to enjoy climbing injury-free.

Author Bio

Christopher David is a Physical Therapist located in Los Angeles, California. He enjoys being active, playing basketball, surfing, and most recently climbing. His passion for Physical Therapy, love of being active, and interest other’s wellbeing drives his practice to help those to overcome injury, return to their previous level of function, and facilitate injury prevention.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.