Climbing Performance Mobility Assessment

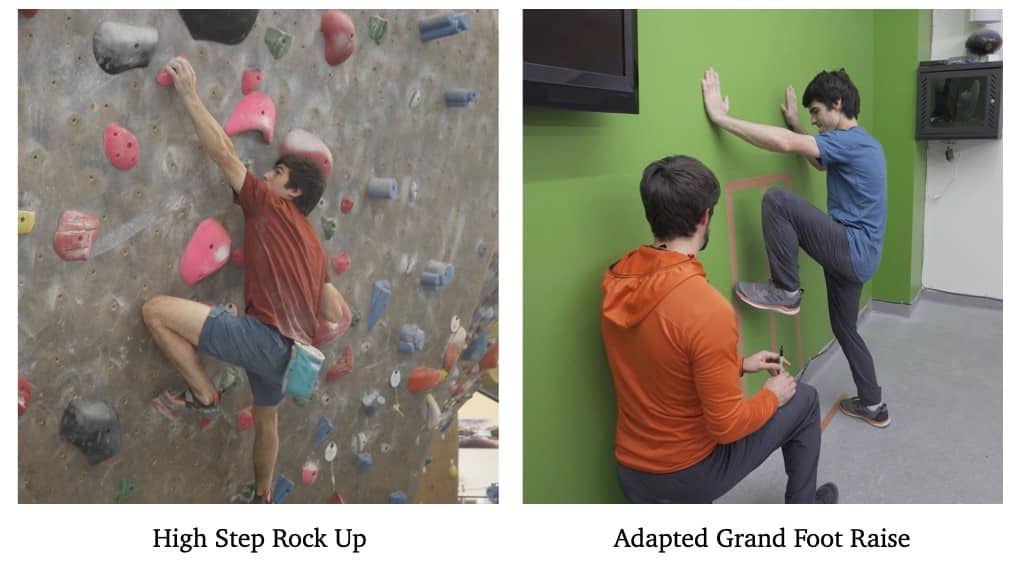

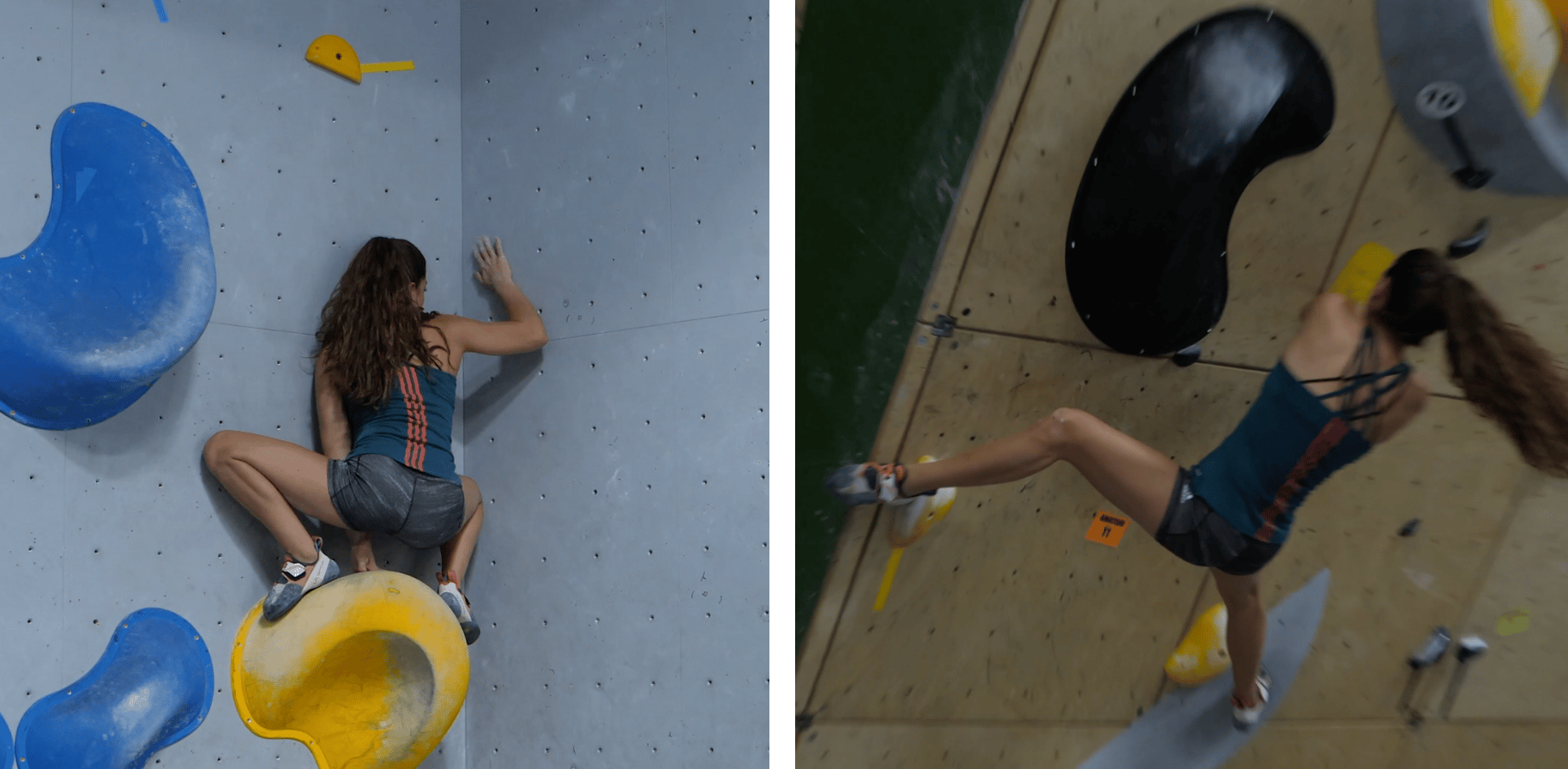

When assessing climbing performance, we look at strength, power, endurance, mobility, and control. In this article, we’ll discuss mobility. Look at the two different movements in the photos below, both of which are high steps. On the left, Jon Cardwell performs a high step rock-up, rocking his weight over his foot. The photo on the right illustrates a heel-hook high step; Brooke Raboutou throws a high heel hook, high-steps onto that foot, and transitions her weight onto that limb so she can reach for the next hold.

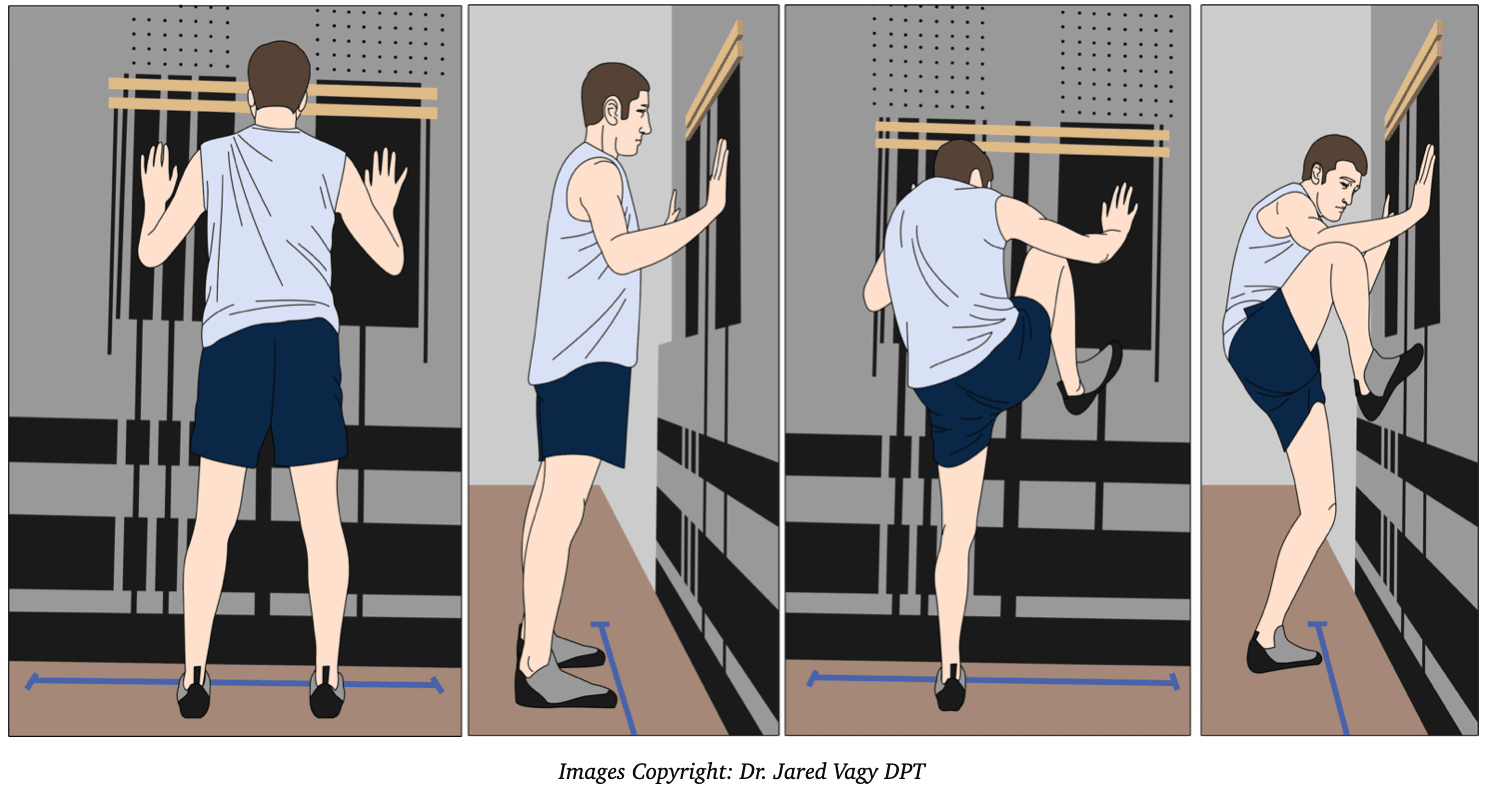

An adapted Grant foot raise is one way to assess the mobility of a climber performing a high step. Nick Draper and his colleagues developed this technique in a study they did on climbing mobility. In this test, a climber stands twenty-three centimeters from a wall, behind a line drawn with tape. (See the illustration below.) They press their hands against the wall, with their palms flat at about shoulder width. They slide their toe up the wall as high as they can with their hip externally rotated slightly and the inside edge of their big toe pressing up against the wall. They can plantar flex on the contralateral side—the only rule is that the palms have to stay against the wall. You then measure the highest distance from the ground to the top of the toe. The climber will perform three practice trials, three test trials, and then an average trial of the three. This test can be normalized by taking a limb-length measurement and dividing that by the total height of the test. It has great inter-rater reliability and relates specifically to the rock-climbing high step.

How to Perform and Stats

-

23 cm from wall

-

Three practice trialsThree test trials

-

Average Trials

-

Normalize height

-

Intra-rater reliability: 0.93

The Adapted Grant Foot Raise

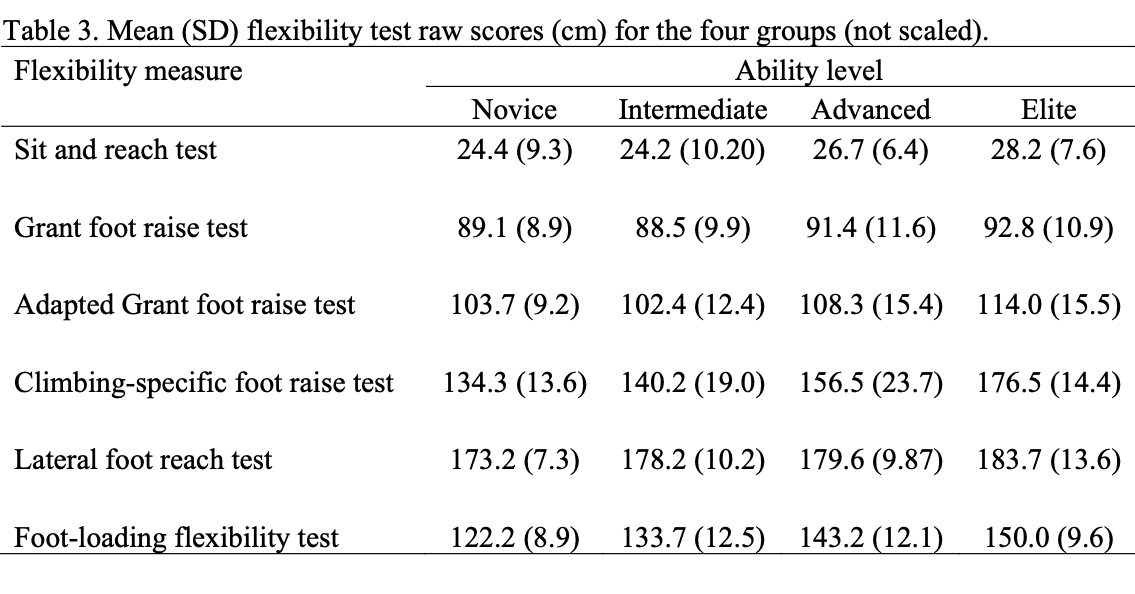

In this study, Draper and his colleagues they took forty-six participants—thirty-four males and twelve females. They split them into different groups: novice (5.6 to 5.8), intermediate (5.9 to 5.10), advanced (5.10+ to 5.13-), and elite (5.13 to 5.14+). They then compared and contrasted these different groups. In the adapted Grant foot-raise test, novice climbers achieved 103.7 centimeters on average, while the elite climbers achieved 114 centimeters, so based on the data in this study, this test can differentiate elite versus novice climbers.

See below for an example of Jon Cardwell performing the adapted grant foot raise.

So how close is this test to actual climbing? Look at the photos below; on the left, Jon Cardwell is climbing, performing a high-step rock-up. On the right, he’s going through the adapted Grant foot raise. His movements are very similar, but they’re not exact.

A common movement fault, which you may see in a climber who has an inadequate adapted Grant foot raise, is a lack of isolated inflection while high-stepping. You can compare the two images below and see that Jon is demonstrating what happens with inadequate flexion. The center of mass moves away from the rock wall, and it becomes harder to reach the next hold during a high-step maneuver.

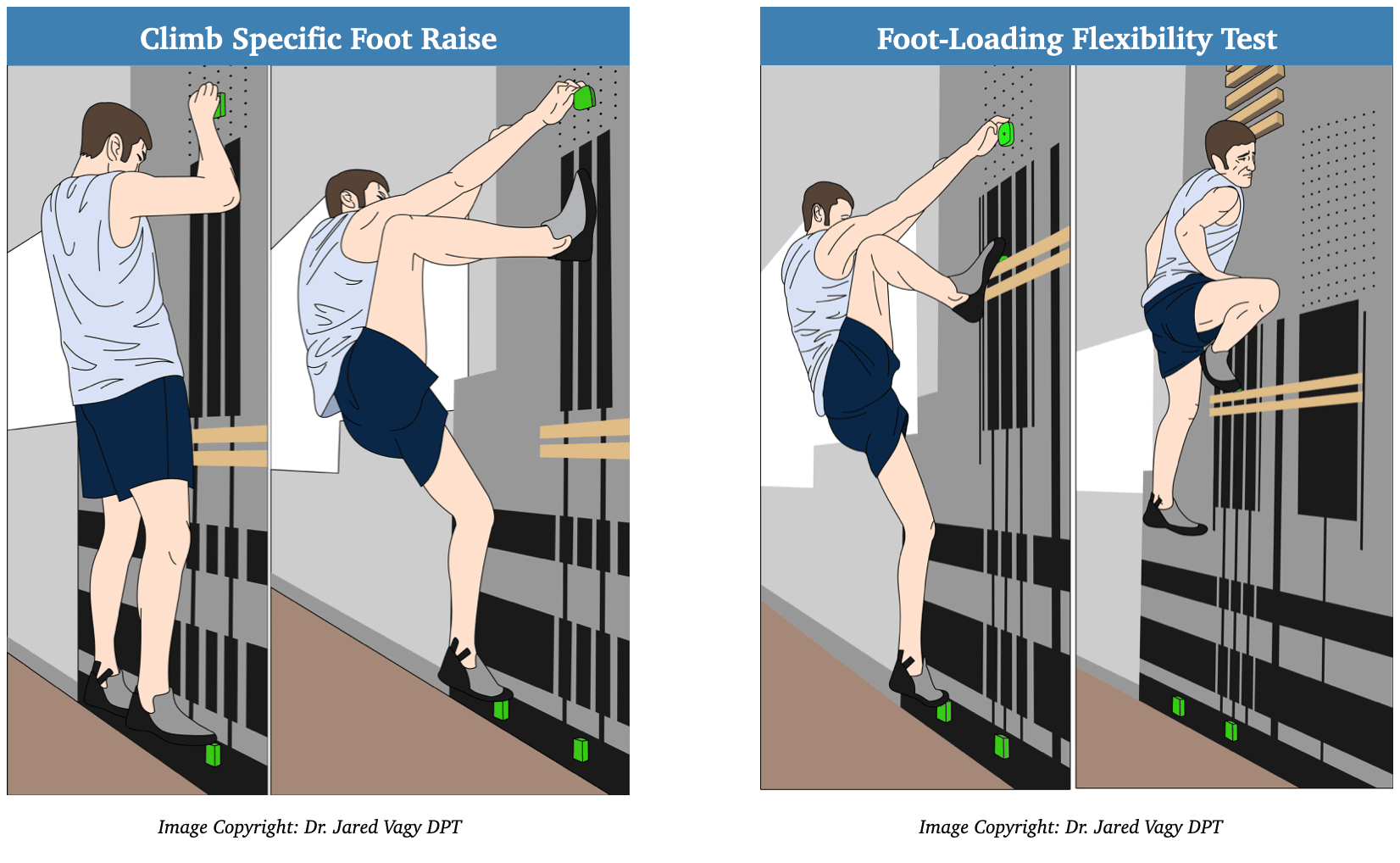

Again, this adapted Grant foot raise is a close but inexact comparison to a high step while climbing. So Draper and his colleagues took it two steps further. First, they performed a climb-specific foot raise from an active starting position. The movement sequence is illustrated below, on the left. The horizontal distance between the hand and the footholds was set to the participant’s bi-acromial breadth and vertical distance to their height.

The test movement included the climber raising the right leg in line with the right foot- and handholds to a maximal position. The score for each climber was measured from the top of the right foothold to the top of the climber’s foot. Throughout the movement, the climber’s left foot had to remain in contact with the foothold and both hands with four digits in contact with the respective holds.

The second progression of the high step that Draper and colleagues tested was the foot-loading flexibility test, shown in the image below, on the right. This test was designed as a measure of dynamic flexibility with the additional requirement that the climber make use of a foot raise or hip flexion to transfer the main part of their mass onto a higher foothold. The ability to make a high-step movement with weight transfer is highly specific to rock climbing. The climber would raise their right foot to a higher hold and then transfer their mass onto that foot. The test was completed when the climber had loaded the hold, as you can see in the image on the far right, with the majority of the climber’s mass transferred onto that higher foothold, with their hips above the loaded foot. Throughout the movement, both hands had to remain in contact with their respective holds. The measurement was taken from the top of the starting foothold to the top of the adjusted foothold.

Draga Foot Raise

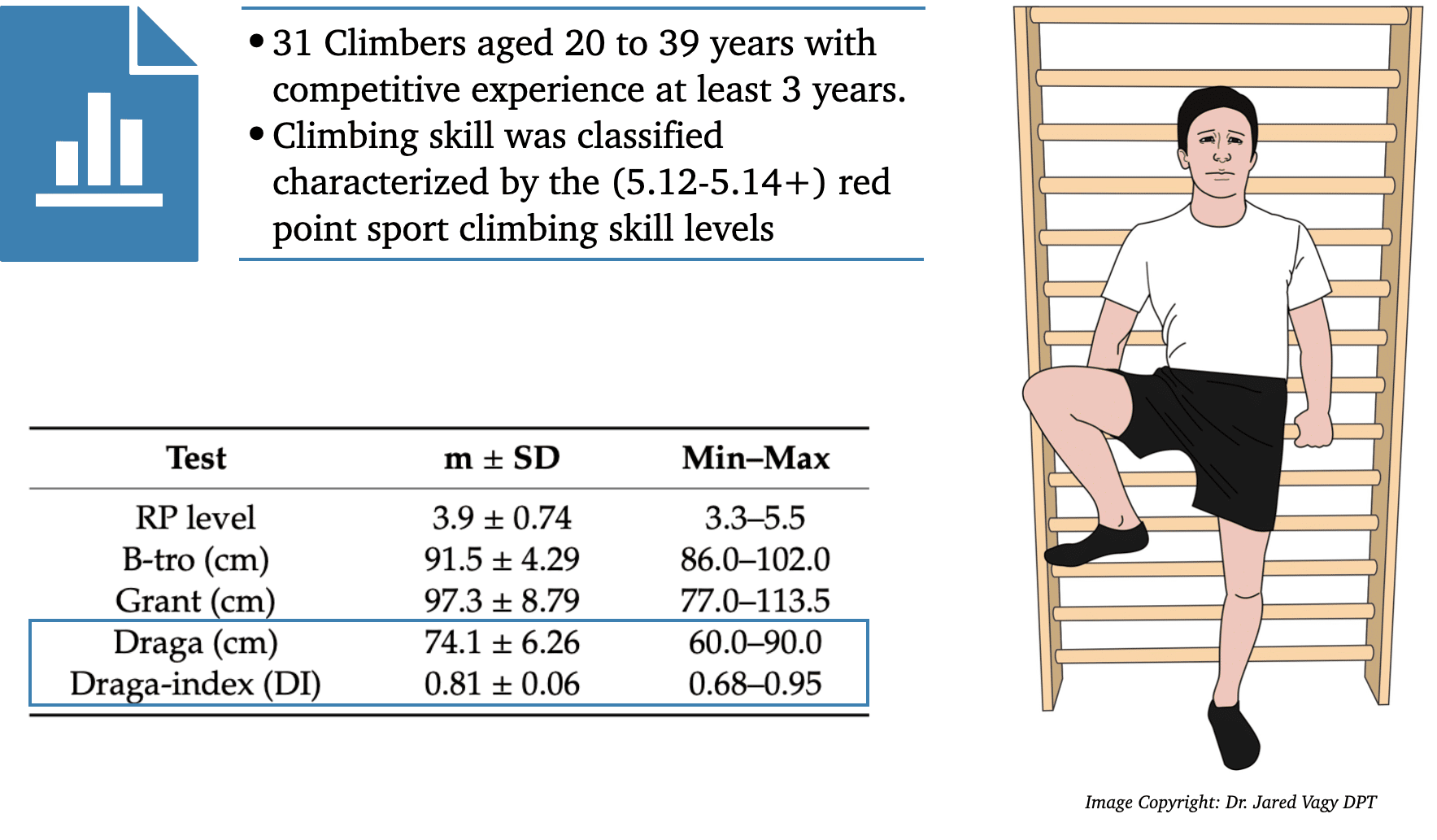

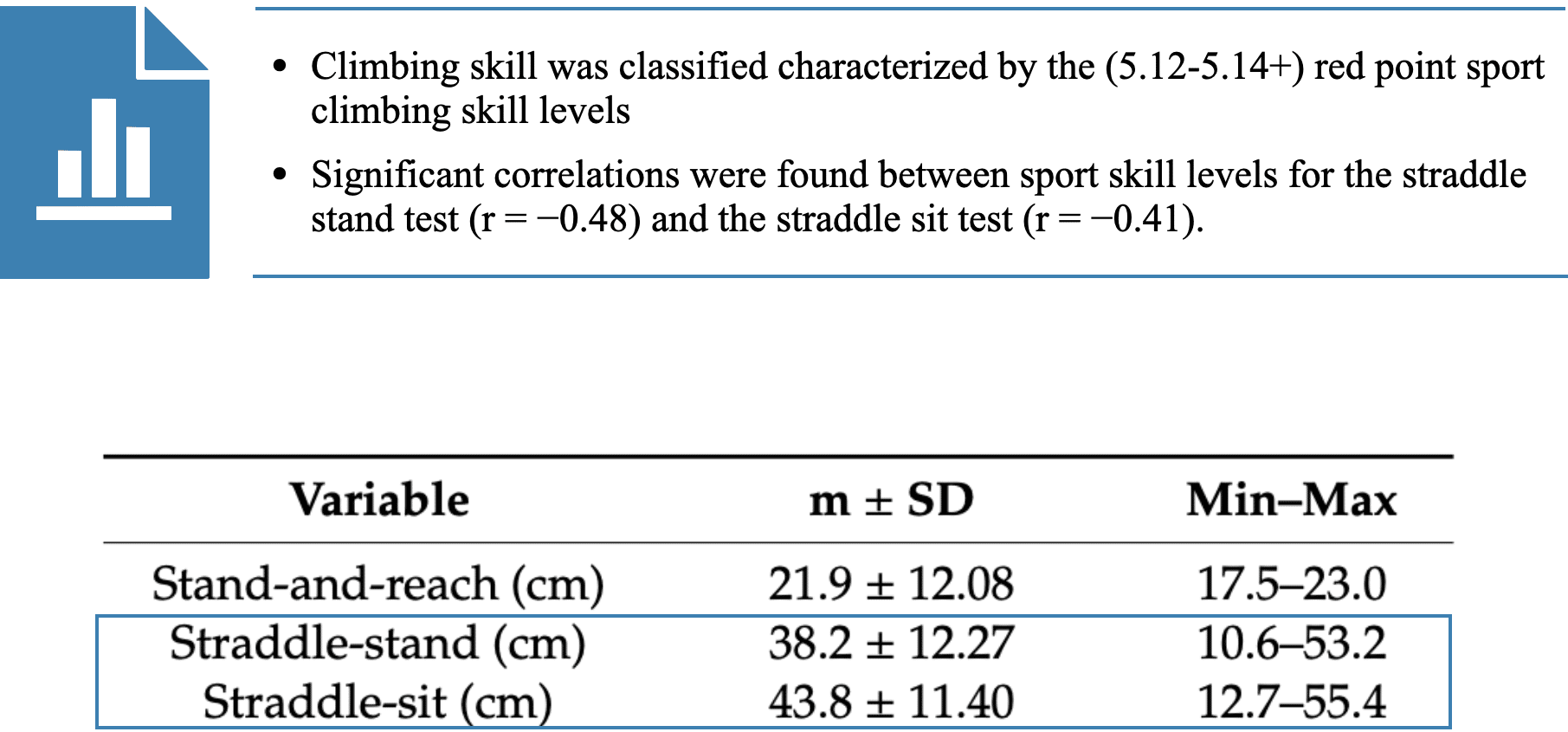

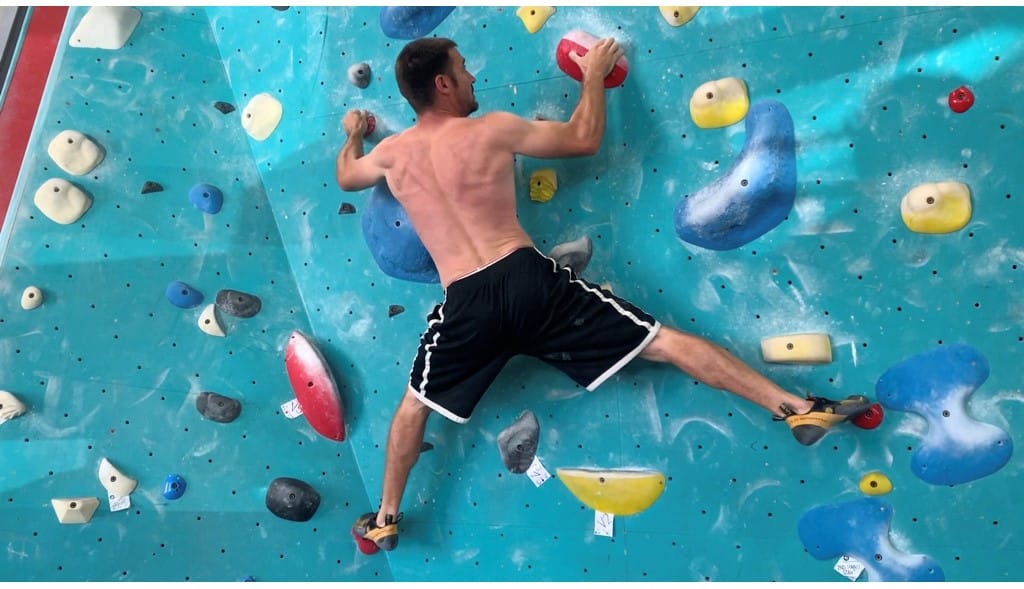

There has been another study that looked at the high-step maneuver. This study looked at thirty-one climbers, aged twenty to thirty-nine years, with competitive climbing experience of at least three years. (See table below.) The climbers had skill levels characterized by 5.12 to 5.14+ with their red point sport climbing skill. As we take a look at this data, the assessment most related to a high step was the Draga test, named after the author of the study. In this test, the climber’s back was touching a measurement board hung on gymnastic wall bars. The climber could also just place their back against the wall.

The climber performed hip flexion, with abduction and external rotation to neutral, with the knee bent. The distance was then measured between the ground and the heel. The results were recorded in absolute and relative values. You can see the raw scores in the chart below. 74.1 centimeters was the average for the Draga foot raise. There’s also the Draga Index, or the DI. And this was the foot raise—the distance from the calcaneal tuberosity to the ground—divided by the climber’s limb length. As you can see, the average was .81 for the Draga Index. This is another way to quantify a climber’s ability to high-step in a climbing-specific assessment.

Now let’s look at a climber’s hip mobility in terms of hip abduction; you often see this during stemming. You’ll also see it in a couple of other movements, so take a look at the photos below. At the lower left, you can see Brooke Raboutou getting into a frogger position on the hold.

Her hips are maximally flexed and abducted. She then pushes out of that position to reach the next hold. In the image at the lower right, she utilizes maximal hip abduction, but she does so while performing a left heel hook. She’s now in this position with the hip more neutral during maximal hip abduction.

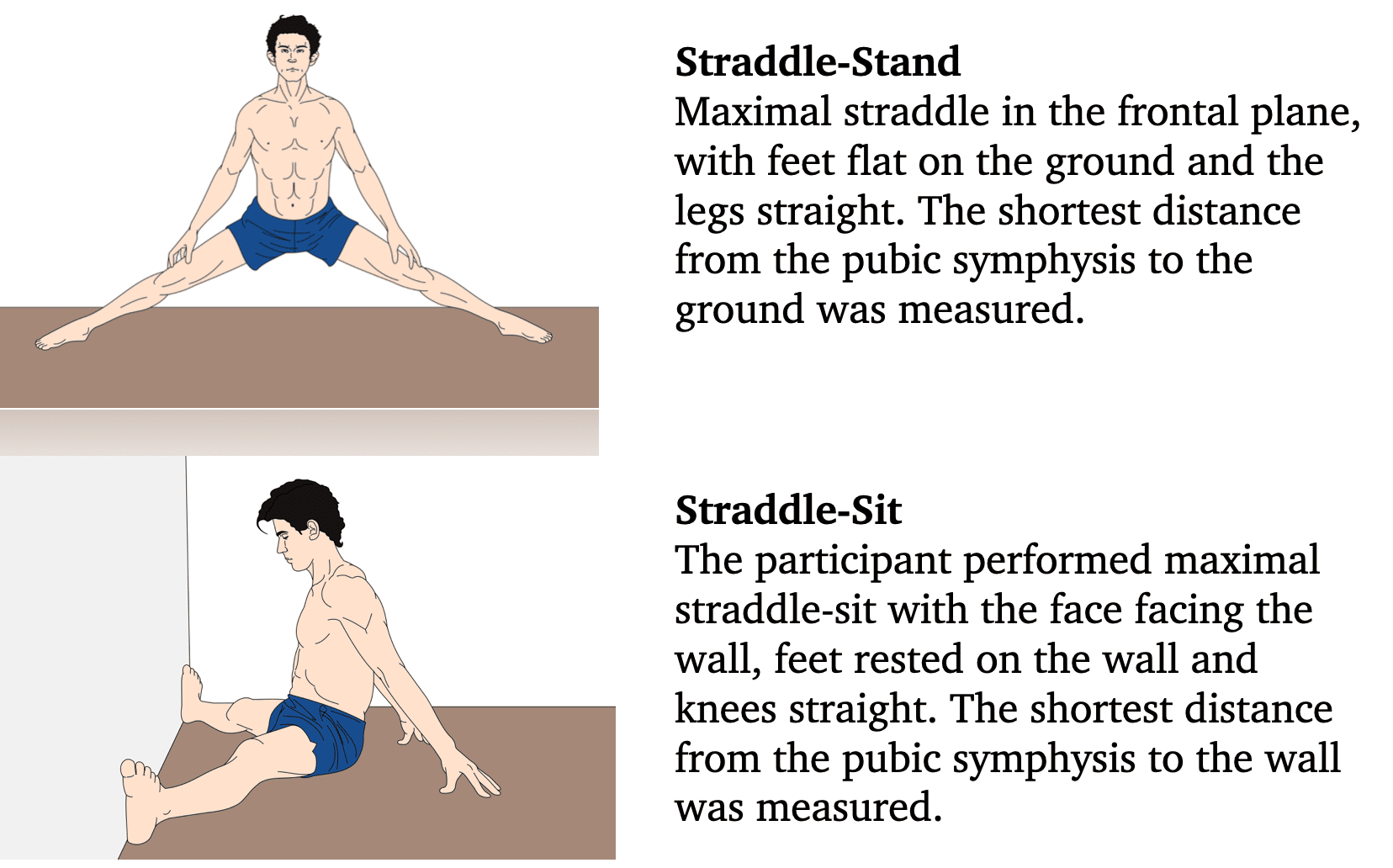

So how do you quantify a climber’s ability to enter maximal hip abduction? We can do it in two different ways, one of which is a straddle-stand and the other which is a straddle-sit.

Straddle Tests

A climber performs a maximal straddle in the frontal plane, with the feet flat on the ground and the legs straight. The shortest distance from the pubic symphysis to the ground can then be measured. You can also use a straddle-sit test to quantify abduction in hip flexion. The climber performs a maximal straddle-sit test facing a wall. Their feet rest on the wall, and their knees are straight. The shortest distance from the pubic symphysis to the wall is measured. Draga and colleagues performed these two tests in their study. They found a significant correlation between sport climbing skill level and the straddle-stand test and straddle-sit tests. (They found a greater correlation, though, with the straddle-stand test.)

As we look at these values in the chart below, we can see that the average straddle-stand is 38.2 centimeters, and the straddle-sit tests averaged 43.8 centimeters. You can compare and contrast these values to the climbing athletes you’re working with.

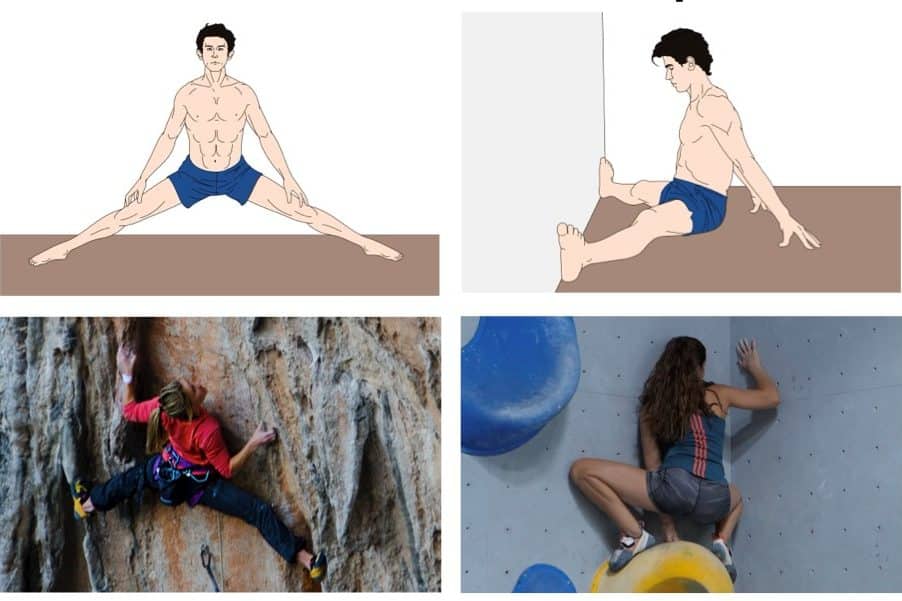

Let’s compare the movement assessment between the straddle-stand test and the straddle-sit test. In the images below, you can see that a straddle-stand test is very similar to stemming, while the straddle-sit test is similar to the frog position while on the rock wall.

Now, there is a drawback to these assessments. They measure bilateral hip abduction with passive mobility—but climbing is active movement! And even climbing positions that aren’t bilateral hip abduction may seem different than these tests. Let’s look at the image below.

You can see as the climber moves that he utilizes maximal hip abduction while climbing, but he leads with one limb, rather than symmetrically stemming.

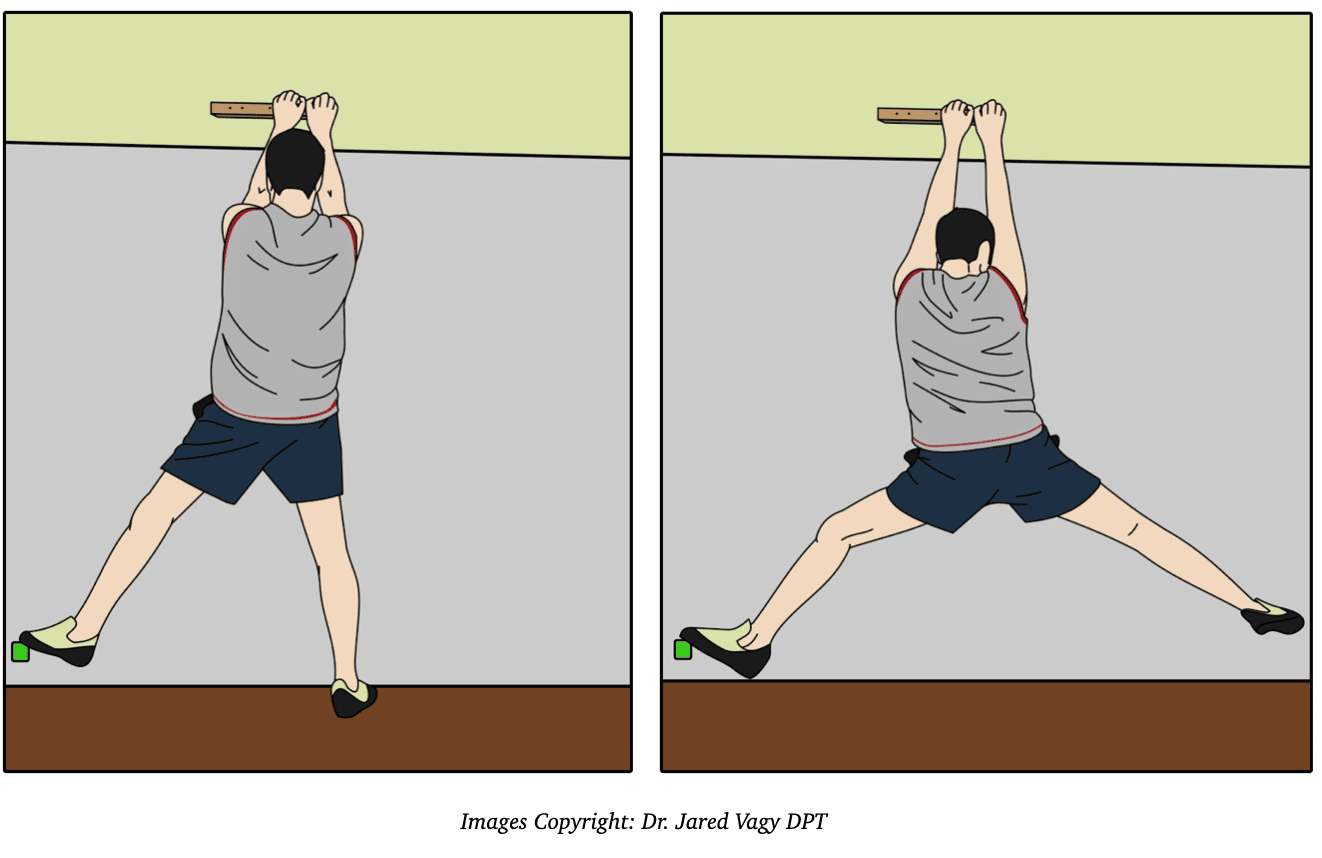

Lateral Foot Reach

So Draper and colleagues tested an alternate assessment (see image below). In this test, the climber performs a lateral foot reach, which is a climbing-specific measure of hip abduction and external rotation. The added advantage of this test is that it’s weight-bearing, and the movement is similar to climbing. An active start position is adopted for the left foot. For this test, both hands were placed on the far-right side of the campus rung, which was located centrally on the test apparatus and set to the participant’s height above the left foothold.

From the starting position, the movement consisted of extending the right foot horizontally to reach a maximal hip-abducted and externally rotated position. The measurement was taken from the outside of the left foothold to the outside of the right foot. Throughout the movement, the left foot and both hands remain in contact with their corresponding holds.

Normative value for this test are (cm)

- Novice: 173.2

- Intermediate: 178.2

- Advanced: 179.6

- Elite: 183.7

Whether a climber is performing a high step, and they need maximal hip flexion, or they’re performing flagging or stemming, and they need maximal abduction, the mobility of a climber’s lower quarter, particularly in their hip, is essential for climbing performance. This post has covered a series of climbing-specific assessments that you can use with your patients to determine their hip mobility for climbing.

Courses for Medical Providers and Coaches

Want to learn more ways to assess, diagnose and treat climbing shoulder and neck injuries? Check out the online course below to expand your knowledge and skillset in the management of rock climbing injuries. Click the course to learn more!

About The Author

Jared Vagy is a doctor of physical therapy who specializes in treating climbing injuries. He is the author of the Amazon #1 best-seller “Climb Injury-Free,” teaches Climbing Injury Professional Education for Medical Providers, and is the developer of the Rock Rehab Protocols. He has published numerous articles on injury prevention and lectures internationally. Dr. Vagy is on the teaching faculty at the University of Southern California, one of the top doctor of physical therapy programs in the USA. He is a board-certified orthopedic clinical specialist. He is passionate about climbing and enjoys working with climbers of all ability levels, ranging from novice climbers to the top professional climbers in the world.

For more education, check out the Instagram page @theclimbingdoctor

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.