Climbing with Shoulder Hypermobility

Have you ever watched a climber contort themselves into seemingly impossible positions to reach the next hold? Their arms stretch out or cross over in ways that shouldn’t be possible, yet for them, it seems effortless, and they appear unaffected by these extreme angles. Or perhaps this reminds you of yourself. When someone is able to perform such acts, it may be because they are hypermobile.

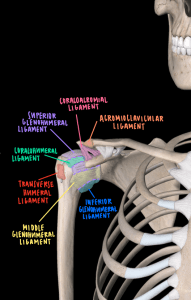

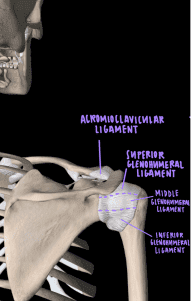

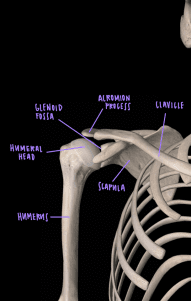

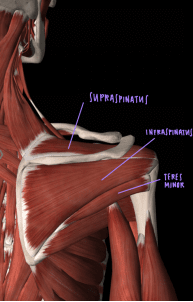

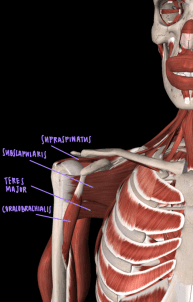

Before going into more detail about hypermobility and climbing, it is extremely important to understand the anatomy of the shoulder complex.

The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint, with the humeral head sitting in the shallow glenoid fossa of the scapula. This type of joint allows for the shoulder to have a wide range of motion. However, due to the shallow nature of the glenoid fossa, the shoulder relies on other structures for stability. These include the static stabilizers (labrum, ligaments) and dynamic stabilizers (muscles) in this region to help maintain congruence.

The above images display the bones, ligaments, and muscles of and around the shoulder complex from anterior (front) and posterior (back) views. Key ligaments that keep the humeral head inside the glenoid fossa are glenohumeral ligaments as well as the coracohumeral ligament. These are our static stabilizers. Key muscles that maintain the shoulder joint stability are the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis).

Definitions:

Now that we understand the anatomy of the shoulder, we can dive into the definition of hypermobility as well as similar diagnoses. A term that may be more familiar to most is double jointed (this is just another term for hypermobility). Hypermobility is defined as the ability of one or more joints to actively or passively move beyond normal limits given the individual’s age and gender. For the purpose of this article we will focus on the shoulder joint, but hypermobility is experienced throughout the body. Typically, this excessive movement doesn’t cause pain and is not linked to any trauma. However, it may increase the risk of shoulder subluxation or dislocation (instability). That said, there are also advantages to hypermobility, which we will discuss later. As we learned previously about shoulder anatomy, the static and dynamic structures help maintain the humeral head in the glenoid fossa. In those with hypermobility, the static and dynamic stabilizers are often lax, which increases the risk for the humeral head to dislocate or sublux, especially when the shoulder is put at extreme angles—something very possible in those with hypermobility.

Facts related to hypermobility:

- Often, a child will have much greater range of motion than an adult.

- Hypermobility is due to the laxity of soft tissue structures such as ligaments, capsules, and muscles that normally prevent excessive motion at a joint. In some instances, the hypermobility may be due to abnormalities of the joint surfaces.

- Hypermobility also occurs in serious hereditary disorders of connective tissue such as Marfan syndrome, rheumatic diseases, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis:

Joint hypermobility syndrome: A connective tissue disorder that results in loose/weak ligaments. This leads to joints that move more than normal and causes the individual pain.

Instability: Instability refers to when the joint is unstable and may dislocate/sublux. For example, shoulder instability can result in the humeral head slipping out of the glenoid fossa. This usually occurs when the lining of the shoulder joint (the capsule), ligaments or labrum become stretched, torn or detached, allowing the ball of the shoulder joint (humeral head) to move either completely or partially out of the socket.

As mentioned earlier, instability can be associated with hypermobility, either congenital or acquired following repetitive stress. When combined, hypermobility and instability can be challenging to treat.

Signs and symptoms:

As hypermobility does not result in pain and is not associated with trauma, the signs and symptoms of it are different to other diagnoses. An individual may suspect hypermobility if they have excessive motion in the shoulder joint. While climbing, they may be able to twist their arm into angles that challenge the limits of human anatomy. Although atraumatic and painless, this can progress to instability of the shoulder and lead to dislocations and subluxations. This will be noticed with recurring subluxations/dislocations, deep shoulder pain, pain with overhead activities, and changes in the appearance of the shoulder joint (compared to the unaffected side).

Assessment:

How to know if you may have hypermobility

Have you been told you are double jointed? Are you able to move your arms beyond what your friends and family can do? These are some clues that you may be hypermobile. However, there are also a few tests that can help you understand even better if you have hypermobility.

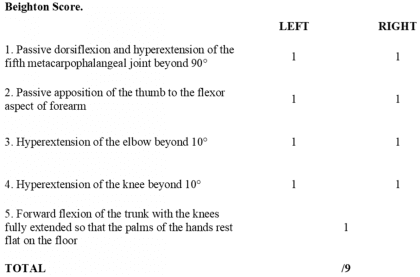

- Gold standard test: The Beighton score. This test analyzes different joints (5th MCP, MCP of the thumb, elbows, knees, spine). If the score is greater than or equal to 5/9, then the participant tests positive for hypermobility. (6/9 for children before puberty, and 4/9 for adults over 50).

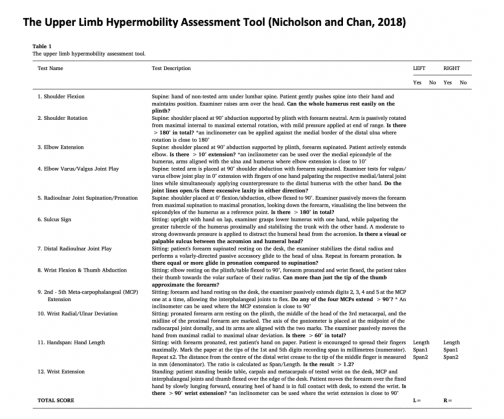

- For upper extremity specifically, The 12-item ULHAT measures mobility of multiple upper limb joints in all movement planes. A score of 7 or more indicated hypermobility.

The following tests are normally performed for instability, however for those who are hypermobile, they may be positive (just painless).

Apprehension test, fulcrum test, relocation

Used to test stability of glenohumeral joint in the anterior direction. A positive result for the apprehension and fulcrum test is determined by apprehension and pain when performing the test. A positive result for the relocation test will be a decrease in apprehension and pain.

Feagin test

Used to assess inferior glenohumeral stability. A positive result is determined by apprehension, pain, or increased inferior translation with a sulcus sign. Compare to the other arm.

Sulcus sign

Used to assess for inferior instability of the glenohumeral joint due to laxity of the superior glenohumeral and coracohumeral ligament. A positive result is determined by a visible sulcus appearing. This could indicate a torn superior labrum. Measure with a ruler and compare it to the other arm.

Load and shift

Used to assess the stability of the glenohumeral joint. A positive result is determined by excessive movement compared to the other shoulder. This would indicate excessive glenohumeral joint laxity.

Note: if there is pain with any of these tests, it may help indicate if there is some instability.

Shoulder Range of motion (ROM)

ROM of the shoulder beyond normal values without pain is a sign of hypermobility.

Normal values include:

- Shoulder flexion: 180°

- Shoulder extension: 60°

- Shoulder internal rotation: 90°

- Shoulder external rotation: 90°

- Shoulder abduction: 180°

Advantages:

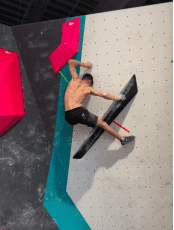

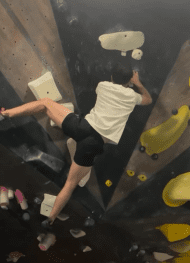

As climbers, we often have to maneuver our bodies into extreme positions to reach the next hold. Hypermobility may allow us to reach the next hold in a way that others cannot due to the increased range of motion. However, we must have the strength and awareness to control these motions. Putting the body at extreme angles without the strength to control it over and over will increase the risk of subluxations and dislocations occurring.

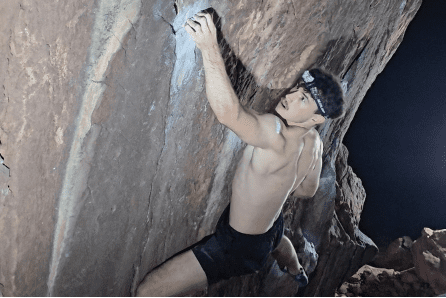

See an example of 2024 Olympic Gold Medalist Toby Roberts displaying both strength and extreme mobility in his shoulders.

From left to right, analyze how his right shoulder moves. The final image shows an extreme excess ROM. This extreme mobility is definitely a contributing factor as to what makes Toby Roberts a fantastic climber.

Complications:

As discussed previously, extreme angles could put the shoulder complex at risk for subluxations and dislocations. This could lead to the individual experiencing instability in the shoulder due to the excessive stress on the joint and surrounding structures that are tasked with maintaining the humeral head in the glenoid fossa.

It is natural to be concerned about the idea of hypermobility, as one may fear that moving their shoulder to such angles could damage structures. They may even begin to avoid certain movements, which will affect their climbing and may have other complications. It is important to note that many top climbers have some degree of hypermobility, so one shouldn’t stray away from climbing with fear of never being able to climb again or reach a high level.

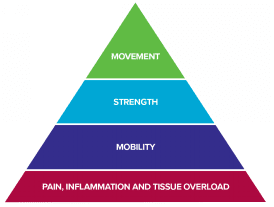

The Rock Rehab Pyramid:

We have now determined that hypermobility is what we are dealing with in the shoulder. Now, what do you do? Stop climbing. No, just kidding! Instead, we will use the Rock Rehab Pyramid from Jared Vagy’s book Climb Injury-Free to go through each stage of rehabilitation in order to enjoy climbing to the best of our abilities. As hypermobility often comes without pain, a large portion of focus will be on strengthening, but this does not mean that we will neglect other aspects of the pyramid.

Unload Exercises:

Education of refraining from extreme ROM

When at extreme angles, be mindful about putting excessive stress on the joint and surrounding structures as this could lead to instability. Gain an understanding of your shoulder ROM by moving your arm into flexion, abduction, extension, IR, and ER while looking at yourself in a mirror.

Taping

This will help by reducing movement of the glenohumeral head in the glenoid fossa. It can help with pain levels and improve function. This is not a permanent fix, but will provide temporary benefits. If you do not have associated symptoms, then do not feel the need to try this method as it primarily helps individuals stay moving when they have instability.

Mobility Exercises:

Thread the needle

This exercise will work on the rotational mobility of the thoracic spine. By targeting this, we can utilize motion from the spine and rely less on extreme ROM from the shoulder.

Scapular push-up (push-up plus)

This exercise will work on the strength and mobility of the shoulder blade and scapular muscles. This will help improve shoulder stability and additionally work on utilizing all of the mobility in the shoulder blade.

Cat cow

This exercise will work on the flexion and extension mobility of the thoracic spine. By targeting this, we can utilize motion from the spine and rely less on extreme ROM from the shoulder.

Strength Exercises:

Rotator cuff strengthening w/ theraband at 90°

We perform this activity to work on the main dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder, the rotator cuff muscles. We use the angle of 90° because this is where we normally have our arms when we climb!

Plank perturbation on a medicine ball/bosu ball/ball/someone pushing you

This exercise will increase stability demands of the shoulder. It can be performed on various surfaces to challenge the shoulder and scapular muscles.

KB carries at 90/90 with emphasis on grip

When holding the kettlebell upside down, focus on gripping as this helps improve shoulder stability. Focus on maintaining proper form as this will enhance rotator cuff activation and work on stabilization of the shoulder.

Movement Exercises: Be aware of movements that may exacerbate pain and understand how to prevent injury!

Dynos

When jumping, utilize your lower legs to explode and generate enough height to be able to grab the hold and engage shoulder musculature before falling down and relying on static stabilizers. Try and use mobility in the spine to gain those last few centimeters of reach.

When landing, think of engaging the shoulders prior to grabbing onto the hold. Aim to grip tightly onto the hold to engage the rotator cuff and help stabilize the joint.

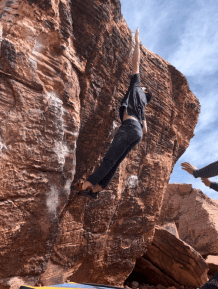

Dispersing your weight

This is a key technique that will not only help prevent injury but also improve your climbing ability by allowing you to better utilize your anatomy. Neglecting this, especially if you have hypermobility, can lead to injuries. Therefore, it’s important to avoid loading most of your weight onto one shoulder. However, if you must engage in this motion, here are a few techniques to incorporate:

- Fully engage the shoulder and scapular muscles: This will prevent the shoulder from relying solely on static structures, which could lead to injury.

- Utilize other structures when possible: Use your feet to help distribute the weight. Be mindful of your foot placement; if your feet drop, it could shift more weight onto your shoulder.

- Shift your weight: Try to position your body under the arm, rather than at a more extreme angle that puts the muscles on strain and puts you at higher risk of injury.

- Grip tightly onto the hold: This will engage the rotator cuff and help stabilize the joint.

Here is an example of what not to do: In the image sequence, the climber reaches out with their right hand and leans to the side, shifting most of the weight onto the right shoulder. Since the arm is not fully extended, the shoulder muscles have to work much harder to maintain this position. In the middle image, the climber releases their left hand and right foot, causing the right shoulder to bear even more of the body weight. Finally, in the last photo, the climber shifts even more weight onto the right shoulder, placing excessive strain on it.

The correction: The climber should have repositioned their feet to avoid leaning so far to the right—by moving the left foot to where the right foot was initially. This would have allowed them to get underneath the hold and reduce the strain on the right shoulder.

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

This article will give you a general idea about a potential condition you may be experiencing. However, if you have recurrent dislocations and subluxations or if you want to take your rehabilitation and injury prevention to the next level, see a physical therapist!

About the author

Stephen Kiraly is a second-year Student Physical Therapist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Ever since he eventually gave in to his friends bugging him to climb, he has not looked back, and climbing has become a central part of his life. Outside of climbing he enjoys running, backpacking, biking, soccer, and basically anything outdoors.

Connect with me @zoliclimbs on instagram.

References

- Blajwajs, L., Williams, J., Timmons, W., & Sproule, J. (2023). Hypermobility prevalence, measurements, and outcomes in childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood: a systematic review. Rheumatology international, 43(8), 1423–1444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05338-x

- Joint hypermobility syndrome: Symptoms, causes, diagnosis & treatments. Cleveland Clinic. (2021). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21763-joint-hypermobility-syndrome

- Nicholson, L. L., & Chan, C. (2018). The Upper Limb Hypermobility Assessment Tool: A novel validated measure of adult joint mobility. Musculoskeletal science & practice, 35, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2018.02.006

- Roberts, L. V., Stinear, C. M., Lewis, G. N., & Byblow, W. D. (2008). Task-dependent modulation of propriospinal inputs to human shoulder. Journal of neurophysiology, 100(4), 2109–2114. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.90786.2008

- Rupp, M. C., Rutledge, J. C., Quinn, P. M., & Millett, P. J. (2023). Management of Shoulder Instability in Patients with Underlying Hyperlaxity. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine, 16(4), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-023-09822-6

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.