Triple Flexion Flexibility Training for Climbers

In the current era of training for climbing, finger strength is all the rage. A quick Google search will turn up no less than a dozen hangboarding protocols, with countless Reddit threads discussing each of them ad nauseam. This is not without some merit. As far as single, measurable metrics go, finger strength has the highest correlation with climbing ability by a significant margin. However, is this correlation high enough that it deserves the current focus (obsession?) that has been put on it in recent years? Has the focus on finger strength in the training-for-climbing community contributed to a neglect of other important metrics? I believe that it has. In this essay I will examine three areas that I believe the training-for-climbing community does not put sufficient emphasis on. These can be summed up in the term “triple flexion” — the flexion of the hip, knee, and ankle joints. In addition to arguing for the importance of training triple flexion, I will give a few exercises that can be implemented to improve range and strength in each area. As a disclaimer, I am not a doctor, nor do I currently have any sort of physical therapy or personal training certifications. I am just a stoked climber.

Hip Flexion

The first, and most significant, area that I believe most climbers fail to focus on in training is hip flexion, and specifically the strength of the hip flexors, which are the muscles responsible for raising the leg. Hip flexion is the act of raising one’s leg, and there is no rock climb that does not involve hip flexion. In fact, almost every leg movement in climbing involves some level of hip flexion. But why do we want to have strong hip flexion — how will it improve our climbing ability?

First, let’s think about hip flexion in the context of less-than-vertical terrain. Often, slab climbs involve small holds and technical movement. Upward progress is primarily propelled by pushing with your legs as opposed to pulling with your arms. Harder slab climbs have limited foot holds, and frequently require lifting your foot up very high to reach them. When the hip flexors are not strong enough (or the hip is too stiff into flexion), the body compensates by bending the opposite leg and pushing the hips back. As most people reading this will have experienced, even a slight shift back in the hips can be the difference between glory, and taking the ride. With better hip flexion, you can get your foot up higher while keeping your hips in more.

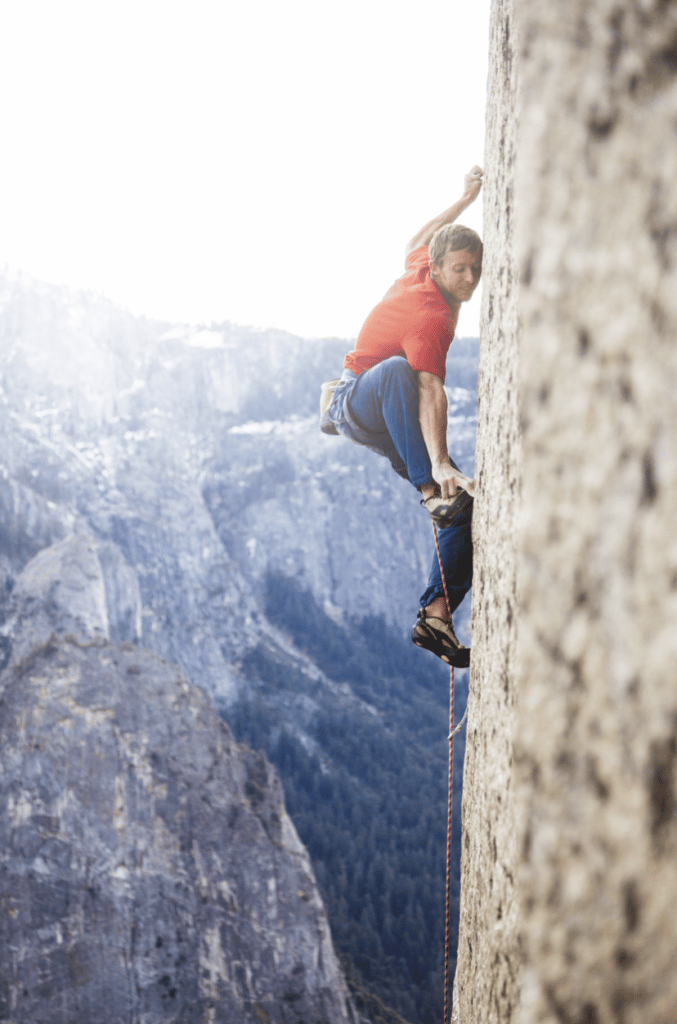

This is demonstrated by the below picture of Tommy Caldwell climbing technical, off-vertical terrain on the Dawn Wall (source: https://www.npr.org/2018/11/20/669573056/dawn-wall- climbers-gripped-razor-thin-edges-up-el-capitans-impossible-face):

Notice how TC’s opposite leg is bent and his hips have extended out from the wall in order to help him reach this foothold. Perhaps with stronger hip flexors, he may have been able to keep his hips in closer to the wall, thus achieving a more ideal position to pull on the left handhold, and in turn executing the move more efficiently. Or it is possible he had to bend his left knee to compress his body into the delicate position, you would have to ask Tommy that one. (note: TC is the GOAT — no disrespect at all to the man).

While strong hip flexors may be beneficial in slabby or vertical terrain, what about when we enter the tilted world? Do we still see a benefit? As it turns out, we do. When climbing overhung terrain, the holds may be bigger, and we may be pulling more with our arms, but our ability to lift our foot high still has enormous benefit. Picture yourself on a 40 degree wall, 40 feet up, racing the pump clock as you’re mid-crux. You make an extended dead point to a grapefruit-shaped sloper. The next move requires getting your left foot on a one-inch wide foothold at hip-level and locking off the sloper to reach a victory jug. The ideal position to lock off the sloper requires maintaining body tension with your hips close to the wall. If your hips come out from the wall too far, you won’t be able to get the ideal position on the sloper, and the lock off move will feel much more difficult. This is because the more your hips sag, the more the force being applied to the sloper will be perpendicular to the ground, which will make the hold feel much worse. Conversely, if you have the ability to reach that foothold while keeping your hips further into the wall, and thus achieving the ideal angle to pull on the sloper (applying force more in line with the angle of the wall, as opposed to pulling down towards the ground), then you will be set up to achieve proper body tension and clip those coveted chains. And this doesn’t apply only to slopers — there are many hold types that we find in overhung terrain for which it is advantageous to keep your hips close into the wall.

To illustrate this, let’s examine a picture of Adam Ondra climbing Les Tres Panes in France (source: https://www.climbing.com/people/adam-ondra-the-future-of-climbing/):

Ondra has phenomenal hip flexion, and this ability allows him to achieve the extremely high foot seen here. For most people, especially those of a similar build to Ondra, this position on the wall would not even be an option, as they could not get their foot up to this foothold while using the handholds seen here. However, because Ondra can, he is afforded more positional options on this climb, meaning that he can maximize his economy of movement.

Let’s now look at this from a training perspective — how do we increase our hip flexion? To increase our hip flexion we have two main aims: increasing range of motion, and increasing strength of the hip flexors. To increase range of motion, there are different stretches that one can do. Personally, I like to girth hitch a thick resistance band around a pole, put this resistance band over the hip flexor of one my legs, and while lying down with back arched and opposite leg flat on ground, pull that knee towards the chest. I hold this for three sets of one minute to one minute and 30 seconds. Here is a videos at 7:08 gives a better idea of how this stretch is performed (source: https://theclimbingdoctor.com/portfolio-items/jared-vagy-on-healing-and-preventing-hip-injuries-in-climbers/):

As for increasing hip flexor strength, there are a number of ways that we can do this. Personally, I like to attach weight to my foot and lift it up (I have just begun to use Monkey Feet for this, which are a great tool). I do an exercise where I use my hands to lift my knee up as far as possible, while keeping my back arched and my opposite leg straight, and then I release my hands and hold my leg at this end range for 10 seconds. It is likely that your leg will drop slightly when you release your hands, and that is okay. Just continue to hold it as high as you can. When performing this exercise, I also like to raise my hands over my head, which helps to ensure that the back stays arched and more closely mimics a position that we may find ourselves in while climbing. This exercise can be done with or without weights. Another option here is to do weighted leg raises. Again, attach a weight to your foot, and then powerfully raise that foot up as high as possible. Then lower the foot slowly and repeat. If you do not have a way to attach a weight to your foot, then you can use kettle bells (just hook your toe under the handle), or you can do weighted hanging leg raises by gripping a dumbbell between both feet.

Knee Flexion

The next area that I believe climbers tend to neglect is knee flexion — the act of bending the leg to bring the heel closer to the butt (i.e. reducing the angle behind your knee). Knee flexion is important in climbing for a few reasons.

First, let’s examine knee flexion in the context of strength. This is particularly beneficial when utilizing heel hooks — having strong knee flexion will increase the force that one can apply when heel hooking. Heel hooks are a commonly used technique in climbing, and being strong in them is a requirement for climbing at a high level. The stronger knee flexion you have, the more you can crank on (or just comfortably use) any given heel hook. Being able to pull hard on a heel hook can be a game changer in terms of taking weight off your arms and increasing movement efficiency. It can even be the difference between being able to do a move and not being able to do that move.

Let’s look at an example (source: https://www.climbing.com/skills/climbing-techniques-how-to-heel-hook/attachment/heelhookpromo-jpg/):

Here, we see that this climber has a high heel hook and is preparing to mantle. In this case, the more this climber is able to pull on her heel hook by engaging the muscles responsible for knee flexion, the less she will have to use her arms, which will ultimately increase her chance of success in topping out the boulder.

Now, let’s look at knee flexion in the context of range of motion of the knee. A common technique used in climbing is rocking over one’s foot. This is a technique that can be utilized on many different types and styles of climbing, and the more comfortable one is in full knee flexion (heel into butt), the more one will be able to utilize this position. Comfortably rocking over one’s foot can be a game changer in terms of achieving resting positions, as well as reaching certain holds. Rocking over one’s foot is commonly done by getting a high heel or toe, and then pulling up and shifting weight onto the foot. The more knee flexion one can achieve, the more one will be able to weight that foot. This translates to more resting opportunities as well as the ability to reach certain holds. In a case where a person cannot achieve full knee flexion, they will have to keep more weight on their hands, and thus may not be able to make certain hand movements, or at least will have to make those hand movements in a less efficient and more difficult manner.

To illustrate where achieving full knee flexion can be useful, let’s look at this picture of a Belgian climber from a recent World Cup (source: https://gripped.com/indoor-climbing/ 2021s-meiringen-world-cup-off-to-incredible-start/):

In this picture, we can see that this climber is in full knee flexion with his left leg. Achieving full knee flexion here allows the climber to put as much weight as possible on that left foot, while simultaneously putting his body in position to use the other holds optimally.

The second area where I see achieving knee flexion as an important skill for climbers, which is slightly more niche, is in the use of kneebars. Often, knee bars require full (or almost full) knee flexion in order to fit into them properly. If one cannot achieve full knee flexion comfortably, they are limiting their ability to perform knee bars, which will in turn make certain climbs more difficult.

This picture of a climber on the route Urban Surfer at Rumney is a great illustration of the importance of being able to achieve full knee flexion in kneebarring (source: https://www.mountainproject.com/photo/107267067):

Here, we can see that this climber must achieve full knee flexion in order to use this knee bar. Because they are able to do this, they are afforded this great resting position, thus increasing their ability to recover and therefore send the route.

As for training knee flexion strength, we have a number of options. There are many different exercises that involve performing knee flexion with added resistance that work well. For example, you can do overcoming isometrics with a cable machine by sitting on a pad or low chair, attaching a strap to your ankle, and hooking that strap up to the cable machine at a weight you are unable to pull. These should be done at various angles of knee flexion. A good set/rep scheme that I have found is 10 seconds on, 30 seconds off for three to five reps per leg, per angle. Repeat for multiple sets if desired. Additionally, you can use the Monkey feet mentioned above and perform hamstring curls. Lastly, Nordic Hamstring Curls are another great way to strengthen knee flexion ability.

If you are unable to achieve full knee flexion comfortably, this is something that in many cases can be improved, it just must be done very slowly and cautiously. Do not work through pain. One exercise that I like for this is the ATG Split Squat. Here, start with one foot in front of the other as if preparing for a lunge, and then bend the front knee while trying to keep the back leg as straight as possible. Your goal is to achieve full coverage of the hamstring over the calf, and then come back up. Regress this exercise by elevating the front foot up to 12 inches. Do not go down deep enough that you feel pain/instability in the knee. Below is an image of the final progression, which is a flat ground, weighted split squat with the front heel on the ground and the back knee off of the ground. Do not start here. In addition to the ATG split squat, static stretching of the quad will help increase knee flexion range (source: https://kneesovertoesguy.medium.com/knee-noise- d94b7e9e0df0):

Ankle Dorsiflexion

The last — and in my view, least important — area that I will discuss here is ankle dorsiflexion. Ankle dorsiflexion is the act of drawing the toes back towards the shin. Having strong and mobile ankle dorsiflexion is beneficial in climbing for several reasons.

First, toe hooking always involves some level of ankle dorsiflexion. It is not uncommon for toe hooks to involve flexing your ankle as much as possible. The stronger ankle dorsiflexion that you have, the more force you will be able to exert in toe hooks, and the more likely you’ll be to send ur proj. Additionally, the more mobile you are in your ankle dorsiflexion, the more options you will have for angles that you can use to apply force on toe hooks, which will in turn increase your movement efficiency by allowing you to maintain ideal body tension, and also taking as much weight off of your arms as possible.

Second, having a high degree of ankle dorsiflexion mobility will contribute to your ability to use certain footholds optimally, especially slopey footholds. This is particularly important in slab climbing. With slopey footholds, we often want to maximize the surface area of shoe rubber that we get on that hold. If ankle dorsiflexion is limited, the body will compensate by bringing the hips out from the wall so that more surface area can be achieved on the foothold. Oftentimes, this makes a climb more difficult, because the handholds must be used in a less-than-ideal fashion if the hips come out too far from the wall.

Now let’s take a look at a more specific example. If you are trying to rock over your foot (shown in the image below), thus increasing knee flexion, but you have poor ankle dorsiflexion, at some point your heel will have to come up, because your ankle is flexed as far as it can go. As a consequence of your heel coming up, the way in which your foot is applying force to the foothold will alter, and you may end up having to use it in a non-ideal position. This is particularly true if the foothold is slopey, and having as much surface area as possible on it will be advantageous. Conversely, if you have a high degree of mobility in your ankle, you will be able to fully rock over that foot while minimizing the need for your heel to come up, and you will therefore have more positional options.

This is illustrated by the picture below (source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9U_qZHv4Fik):

Notice how the right foot is on a slopey volume, and the more surface area of shoe rubber the climber has on this volume, the better positioned they will be. If this climber had worse ankle dorsiflexion, their heel would lift up more, and they would therefore have less surface area of rubber on the volume, which would make this climb more difficult.

The third area where I see having a high degree of ankle dorsiflexion mobility as being beneficial to climbers revolves around achieving high feet, especially in slabby to vertical terrain. In cases where a foothold is just barely within reach, occasionally having a higher degree of ankle dorsiflexion could be the difference in achieving the top of that foothold, and not quite being able to use it. Admittedly, situations in which this is the case are not particularly common, but they do arise.

There are a few things that we can do to improve ankle dorsiflexion range and strength. For increasing range, I like to do a soleus stretch. Here, I start with hands against a wall and front foot a couple feet back from the wall. I then bend my front leg such that my knee goes over the front toe, while keeping my heel on the ground. You should feel this in your soleus, towards the bottom of you calf. I hold this for three sets of one minute on each side. Additionally, the aforementioned ATG Split Squat can help to increase ankle dorsiflexion range.

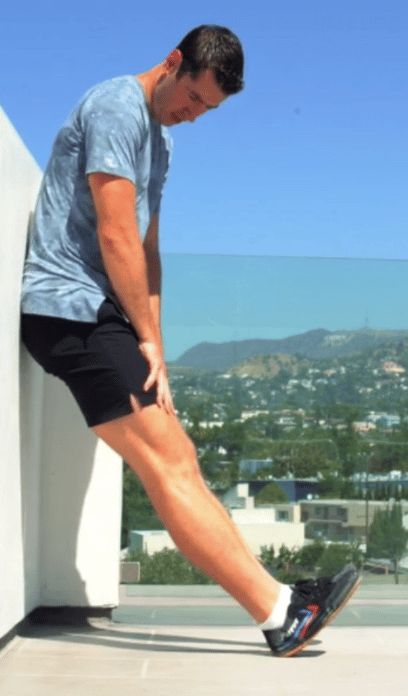

For increasing dorsiflexion strength, we want to increase the strength of our tibialis anterior, which is the primary muscle responsible for ankle dorsiflexion. To do this, we can simply stand with our butt against a wall and feet one-half to one meter out from the wall (the further out your feet are, the more difficult the exercise). From this position, raise your toes up as far as possible, and then lower them down slowly. I like to do two sets of 25 reps for this exercise. Here is what it looks like (source: https://kneesovertoesguy.medium.com/knee-ability-zero-549bb9889698):

Eventually, you will likely want to add weight to this exercise. This can be done by utilizing a resistance band, kettle bells, or by using a “Tib Bar”, which is an uncommon training device also known as a DARD. They can be found several different places online, and this is an example of what one looks like (source: https:// www.mercuryandthorfitness.com/products/shin-blaster-anterior-tibialis-trainer):

Bringing this essay back full circle, I want to be clear that I do not believe climbers should stop focusing on training finger strength. As mentioned in the first paragraph, it is one of the most important metrics for climbers — likely the single most important. My argument is that there is a current infatuation with finger strength in training for climbing circles, and this focus has contributed to a neglect of other important areas. I have discussed three of these areas here — hip, knee, and ankle flexion — and I believe many climbers could see gains if they began to train these areas with intention. Lastly, in addition to all of the aforementioned benefits, increasing range and strength in the hips, knees, and ankles will help make climbers more resistant to injury, which is another huge advantage that will help contribute to long-term health and gains. Climb on!

About The Author

Joel May is an aspiring DPT student and climber of 7 years, based out of Denver, CO. During the past couple years, he has given much thought to what it takes to become a high level climber, and has been focused on ironing out his weaknesses, especially in regards to mobility. Joel enjoys all disciplines of rock climbing, but is particularly fond of sport and trad. His hardest send to date is a 5.14a sport climb. When not climbing or training, Joel can be found spending time with his girlfriend, Molly, and dog Momo, as well as boring his friends with philosophical musings.

For contact info, I can be reached on Instagram @joelmarshallmay and email at joelmpmay@gmail.com.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.