Train Climbing Route Speed, Movement Cadence and Technique

In this article, we will take a closer look at train climbing route speed, movement cadence, and technique. When analyzing climbing movement, there are five key components to look at: speed, hold contact, intensity, style, and alignment. Let’s begin by first looking at speed.

Static Climbing Movement

The below video displays a climber that is climbing statically. Watch as Brooke Raboutou moves on the wall in a slow and rhythmic manner. This is a chosen climbing style; some climbers will climb statically on all routes while some climbers choose to climb statically selectively during a route. It’s important to understand the baseline speed of a climber so that we can further interpret how and why they develop their injuries.

Now, when we notice that a climber is climbing statically, we want to apply some type of drill to increase their movement repertoire. Although helpful while climbing for control, static motions don’t always allow a climber to cut loose. So, in this case, an interesting exercise would be the pull and clap. With the pull and clap, start with an easy route. Every time that we pull to move to the next hold, we clap our hands. It is a little bit of a goofy drill, and it’s audible performing it in a climbing gym, but it’s important for the climber to start to develop that elasticity in that dynamic power wall climbing. So, let’s look at the image below of a climber climbing too statically, then apply the pull and clap movement drill to climb more dynamically.

Dynamic Climbing Movement

Now let’s take a look at the other end of the spectrum in the below video; we now have a climber who’s climbing dynamically. Climbing with too much dynamic motion can shock load or overload the system, so it’s important to teach climbers who climb too dynamically another skill set or an option to move more statically.

A drill that’s often used that’s helpful for this is the hover drill. With the hover drill, we want to do it on an easy route or have the climber do it on the easy route. As they climb, they’re going to hover and wait three seconds before they grasp the next hold. They’ll then hover their hand right before they contact the hold and wait about three seconds until they grasp the hold. This allows the climber to learn self-control and the ability to maintain overall body tension while moving from hold to hold. It can treat and show the climber how to move in a more static style. Let’s take a look at the hover drill in the below image.

The climber starts on an easy route; they will climb and hover their hand three seconds over every hold before grabbing the hold. This forces the climber to perform each move statically while they determine the best body position before they move. This is a great drill to train more static motion for a climber that climbs too dynamically.

Route Speed and Move Cadence

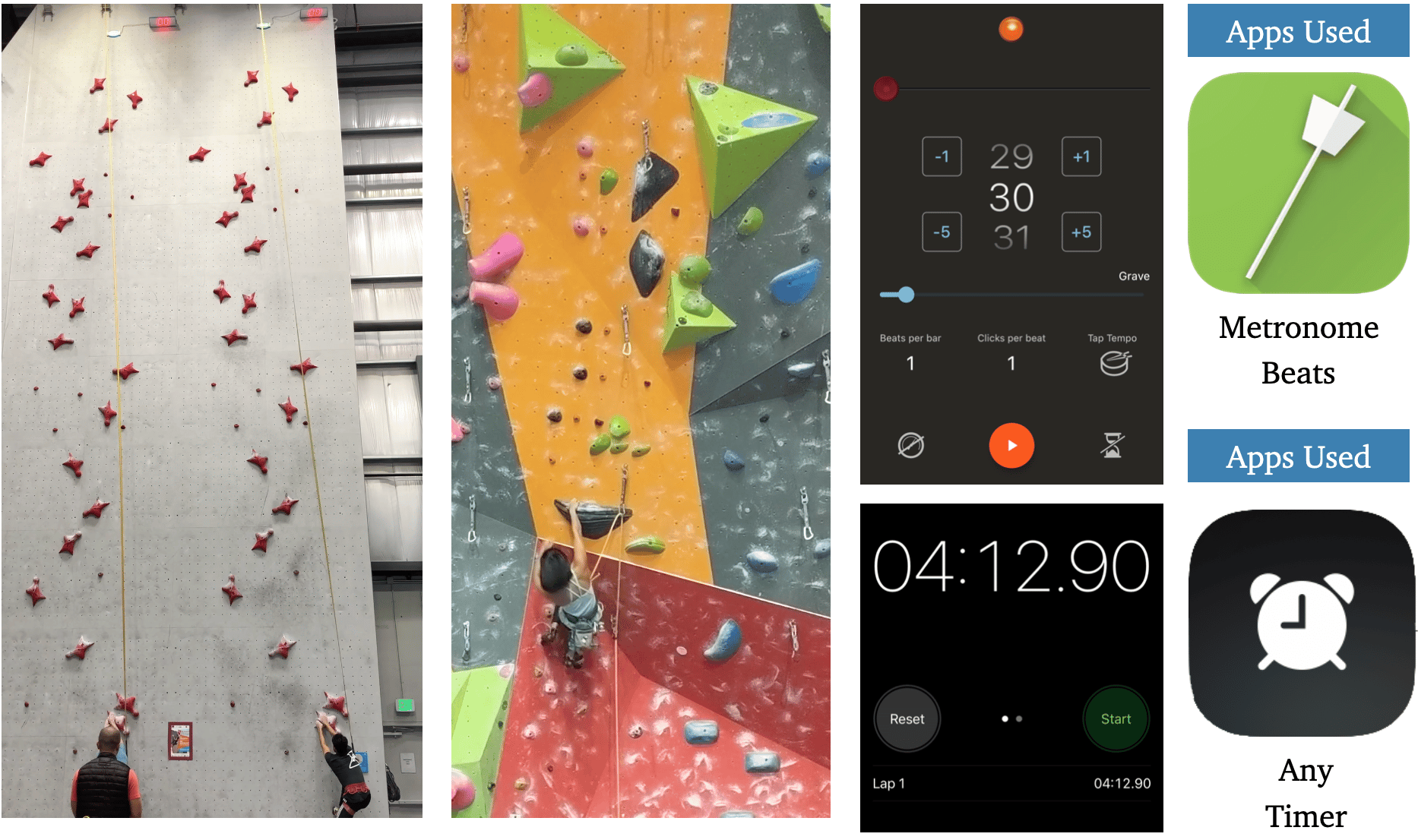

Now we have talked about static and dynamic climbing, but it’s also important to think about route speed and cadence. Take a look at the image below. I’m on the left, and this is the first time I ever got on a speed wall. Let’s compare and contrast me and my friend, Kelly, regarding the different speeds that we’re climbing and the cadence of motion and movement in between holds. In addition, let’s examine the overall speed, time, and the different sticking points when one of us speeds up or slows down.

I hate to admit it, but Kelly beat me in this exercise. She had a much faster time than me; I also have to admit that this was our first time on the speed wall. After this exercise, I became a little bit obsessed and kept running laps on it, lowering my time incrementally, and then raced Kelly again. And she beat me, again.

So, it’s interesting to see that while climbing, we have our overall route speed, which we saw when Kelly beat me as she had a quicker time. Next, we have our move cadence. Towards the end of the speed wall, I started getting a little quicker and increasing the cadence of my movement, but I still lost. As we go through this, we can look at climbers on a route and search to determine their route speed and their cadence.

When we look at a static climber, they’ll typically have a slower route speed and a slower move cadence. When we look at a dynamic climber, oftentimes, they can maintain that dynamic elasticity throughout the route, meaning they’ll have a faster speed and cadence. But we’re really interested in looking at climbers that change their move cadence throughout a route; maybe they move faster on easy movements and slower on more difficult movements. While this is important for climbing performance and energy efficiency, it really allows us to home in on climbers and potentially put them in different scenarios to train these different speeds. Allowing them to utilize more efficiency with movement but also try to prevent injuries.

Let’s take a look at the above image. On the left, we have a speed climber race, and we can see they obviously are much more trained than Kelly and I are in these movements. When we look at the top speed climbers in the world, they’re moving much faster; they are practically running up the wall.

Now, let’s take a look at the image on the right that depicts a sport climber by looking at the speed of the route and the cadence of movement. If we were to take a metronome, we could start to map or quantify how the climber is moving and their patterns. We can take a metronome beat app and measure the beats of every movement. We could then start to see when the climber is struggling and when they’re climbing smoothly. Finding a consistent speed for that climber during certain will allow us to compare it to their overall speed while climbing the route.

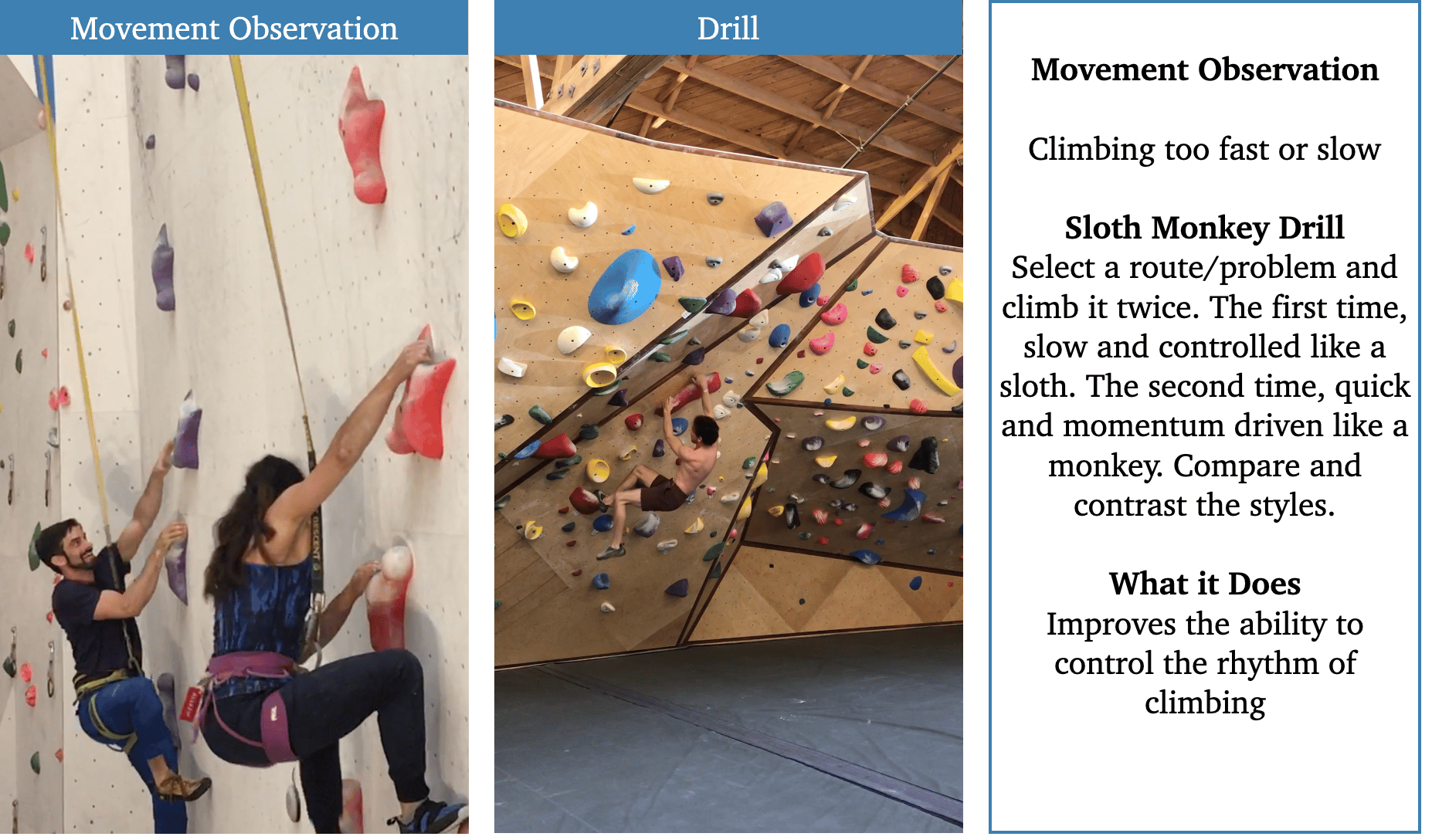

Now, if we have this data, it is objective data: overall speed and this metronome timing of this cadence in between movement. However, we can also have the climber check-in subjectively. A great way to do this is the sloth monkey drill, a drill that I learned from Chris Hampton of Power Company Climbing. With this drill, the climber will select a route or problem that they will need to climb two different times.

The first time they climb the route, it should be slow and controlled, just like a sloth, paying attention to nuances of movement and then slowly making their way up to the top of the problem. They will then drop back down, and the second time they will climb it quickly using momentum and driving their motions just like a monkey would while it’s climbing. They will climb to the top of the route, drop down, and then compare the two styles.

This is a way to check in with our bodies and see how we are feeling and how we are moving at quicker and slower speeds. This information is essential to give climbers the tools to diversify their speed of climbing as well as their route cadence.

Overall Understanding

By understanding move cadence and route speed, and dynamic and static climbing styles, we can watch a climber move, and as a medical provider, start to determine the reasons why a climber is moving a certain way. We can use this information to broaden their style, their skills, and their ability to either shift the pendulum towards a more static technique when needed or towards a more dynamic technique or style when needed.

Irregularities between climbing movements, especially during cruxes, will allow us to home in on move cadence and the overall route speed giving us information on the efficiency of the climber.

Courses for Medical Providers and Coaches

Want to learn more ways to assess, diagnose and treat climbing shoulder and neck injuries? Check out the online course below to expand your knowledge and skillset in the management of rock climbing injuries. Click the course to learn more!

About The Author

Jared Vagy is a doctor of physical therapy who specializes in treating climbing injuries. He is the author of the Amazon #1 best-seller “Climb Injury-Free,” teaches Climbing Injury Professional Education for Medical Providers, and is the developer of the Rock Rehab Protocols. He has published numerous articles on injury prevention and lectures internationally. Dr. Vagy is on the teaching faculty at the University of Southern California, one of the top doctor of physical therapy programs in the USA. He is a board-certified orthopedic clinical specialist. He is passionate about climbing and enjoys working with climbers of all ability levels, ranging from novice climbers to the top professional climbers in the world.

For more education, check out the Instagram page @theclimbingdoctor

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.