Tendons: do I load it or rest it?

Tendons are a hot topic in the climbing world and with good reason. Tendon pain from acute injuries or chronic degeneration are very common among climbers because of the extreme stress we put on our bodies and the repetitive nature of the sport. The first and most important question when it comes to tendon pain is: should I rest it or load it?

There are times when either answer is true. Loading a tendon when you should have been resting can lead to increased inflammation and a significantly longer recovery time. Resting a tendon when you should be loading can also cause the tendon to weaken and for degenerative changes to take place. By the end of this article you’ll be able to tell when you should rest and when you should load. We’ll also discuss the best ways to load, how much and how often to load and how to progress.

By the end of this article you’ll be able to:

- Tell when you should rest and when you should load.

- Know the best ways to load, how much and how often to load and how to progress.

What Causes Tendon Injuries?

Very simply, every tendon has a certain capacity. If you acutely or chronically overload a tendon you will develop a tendon injury. This most commonly happens after the climber has done “too much too soon after doing too little for too long”. Returning to climbing too quickly after an extended break is a great way to end up with a tendon injury. For tips on how to return to climbing safely, read this article. Remember that muscle adapts more quickly than the collagen in tendons so muscle gains can easily outpace tendon adaptation.

Tendons also get injured with rapid increases in training volume or intensity or even when switching from one discipline to another (ropes to bouldering is most common!).

Tendons also get injured when muscle compensations or movement errors are occuring. Imbalances in certain muscle groups will cause excess stress to certain muscles, leading them to get overloaded even without big changes in your climbing volume or intensity.

Examples:

- If your rotator cuff muscles are weak, your proximal biceps tendon is likely to compensate and develop tendinopathy over time.

- If your wrist and finger extensor muscles are weak then your wrist and finger flexors will work excessively which can cause medial elbow pain (golfer’s elbow) or lateral elbow pain (tennis elbow).

- If your core and glute muscles are weak then your hamstrings will take excessive load while heel hooking which often leads to hamstring tendon injuries.

Do you have tendinitis? Or tendinosis? Or tendinopathy?

Tendinitis is one of the most commonly diagnosed tendon injuries, but this is a misdiagnosis more often than not. The latest research on tendons shows that if you’ve been experiencing pain in a tendon for more than 72 hours it is likely that the inflammatory response in your body has run its course and there are no longer any inflammatory chemicals or “markers” left in the injured tissues. At this point we call it “tendinosis”. This distinction is important because treatments that are designed to target inflammation (NSAIDs, ice, resting) are much less likely to be effective in this stage.

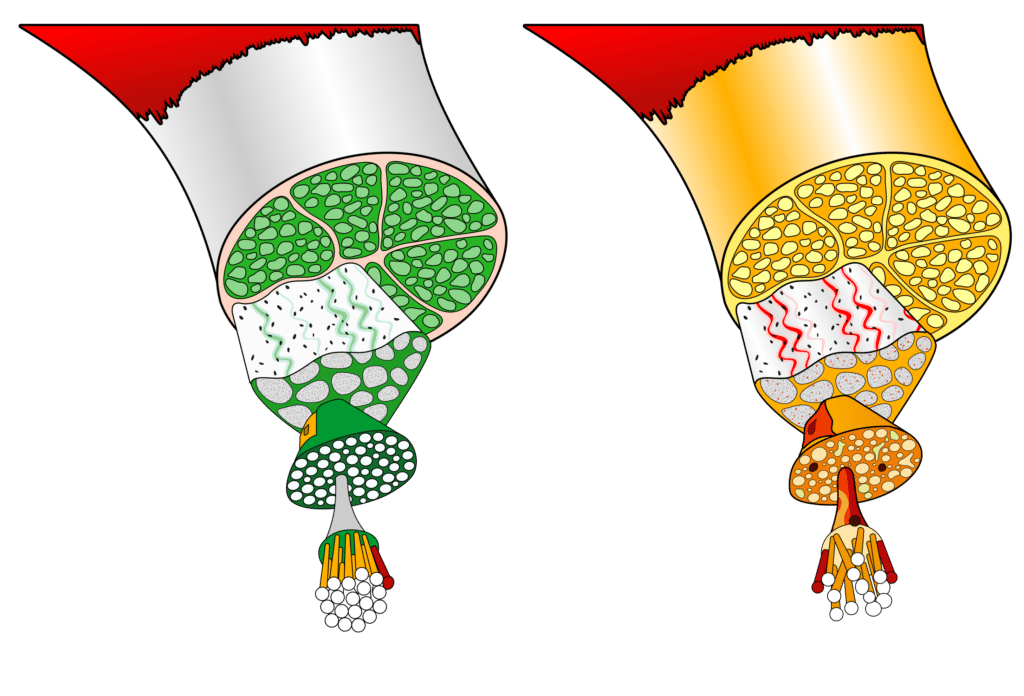

If tendon pain has been present for more than 3 months, we call it “tendinopathy”. This is also an important distinction because the treatment techniques will also change when you have tendinopathy. If a tendon has been painful for over 3 months there are likely degenerative changes to the tendon. Slightly in depth description of what is happening at the cellular level. Below you can see on the left, a normal healthy tendon, and on the right you can see a degenerative tendon with rounded fibroblasts, increased ground substance, capillary ingrowth, and disorganized type I and III collagen fibrils.

The most common areas of tendinopathy in rock climbers are:

- Lateral elbow tendinopathy (tennis elbow)

- Medial elbow tendinopathy (golfer’s elbow)

- Supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendinopathy (rotator cuff syndrome)

- Biceps long head tendinopathy

When you have tendinopathy, that tendon has:

- Greater blood vessel and nerve infiltration (which makes it more painful)

- A larger proportion of type II and III collagen (which makes the tendon weaker)

- Increased interfiber matrix (which can cause visual and physical deformation)

- A more disorganized collagen fiber arrangement (which also makes the tendon weaker)

- Decreased elasticity

For treatment of tendinopathy various modalities such as cortisone injections, shockwave therapy, ultrasound, low level laser and cross friction massage have very conflicting data to support their effectiveness. Based off of a mountain of good research we know that progressive, targeted mechanical loading works for the treatment of tendinopathy.

Tendinitis |

Tendinosis |

Tendinopathy |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Definition |

Acute injury to a tendon including microtrauma from repetitive loading or stretching. Inflammatory chemicals will be present along with swelling. |

Medium term degeneration of a tendon without the presence of inflammation. Characterized by mild changes to the collagen structure of the tendon. |

A tendon with long term degenerative changes and a failed healing process. Characterized by significant changes to the collagen fiber type and structure of the tendon. Pain has been present for over 6 weeks. |

Timeframe* |

2-3 days but inflammation and pain can persist for 2-3 weeks if the tendon is not rested properly. |

3 days to 6 weeks. With tendinosis the inflammation process has resolved, even if pain is still present. |

Can begin as early as 6 weeks and will progressively get worse over time if not managed effectively. |

Symptoms |

Aching or sharp pain that is accompanied by redness and maybe swelling. It usually doesn’t get better as you warm up. |

Aching or sharp pain without redness or swelling. Will often get better as you warm up and worse after you cool down. |

Aching or dull pain that gets better when you warm up and worse after you cool down. It has a significantly delayed response and will often be most painful the day AFTER you use it. |

Treatment goal |

Reduce inflammation and pain |

Reduce pain and load management |

Optimally load the tendon for healing, progressive load management |

To Load orNot to Load?To load or rest? |

Rest- early loading can cause increased inflammation and prolong recovery times. |

After pain has mostly resolved, initiate mild isometric loading with cautious and mindful progression. |

Rest at least 3 days, then initiate moderate isometric loading. Progress continuously as tolerated. |

*Note that this is not necessarily a linear progression from itis → osis → opathy One can develop inflammation (itis) within a degenerative tendon (opathy).

As noted in the chart, this is not a linear process from itis to osis to opathy. You can develop degenerative changes to your tendons without the presence of pain and never actually go through the initial injury and inflammation process. It’s frustrating that sometimes you can’t even feel the degenerative changes developing, but remember that if you manage it early, tendinopathy is very treatable and there are usually ways you can continue to climb during the healing process.

How long should I rest after a tendon injury?

If you previously had no pain prior to your tendon injury it will be ok to assume that you are experiencing tendinitis and it is recommended that you rest for a minimum of 3 days to prevent further inflammation. But remember that the inflammatory process can persist for several weeks if you don’t rest it properly so I recommend that you rest for a minimum of 7 days for mild injuries (minimal swelling and pain up to 4/10) and a minimum of 14 days for more severe injuries (a large amount of swelling or over 4/10 pain) or until the swelling has subsided before initiating any kind of loading.

If you previously had pain and you flared up a current tendon injury, it is likely that you had tendinopathy previously and the degenerative tendon is reacting to overload. Because there is likely no inflammation present we don’t need to be quite as concerned about a prolonged inflammatory response. It is still recommended that you rest a minimum of 3 days before initiating loading but starting with resting for 7 days will allow the pain response to calm down more fully and you can be more assured you’re safe to load. This type of pain actually responds well to graded loading. Start with isometric exercises at 40% of your 1 repetition maximum (the maximum weight you can hold without pain). One protocol that works well is to load the tendon isometrically for 5 reps of 45 second holds, 2-3 times per day in the early phases of the rehab process.

Rest does not have to mean completely not using the tendon. General light movement is beneficial for reducing inflammation and pain but you should avoid adding any kind of external load to the tendon during your rest period.

What’s the best way to load?

There are literally dozens of different evidence-based loading protocols for tendons. Some call for heavy, slow eccentric reps, some for long duration isometric holds, while others are more traditional and have similar parameters to hypertrophy training. To simplify things you’ll want to load the tendon between 60% and 90% of your 1 repetition maximum (1RM) aiming for 3-4 sets of 8-15 repetitions. Start at a lower intensity with higher repetitions initially (4 sets of 15 reps at 60% 1RM) and progress to higher intensity with fewer repetitions (3 sets of 8 reps at 90% 1RM) over an 8-12 week period.

Here are the recommendations when choosing your loading method:

- Isometrics are the safest and usually the least painful way to initiate loading. This is a good place to start.

- Eccentric-only loading is often less painful than concentric loading and allows you to use heavier weight. Use eccentric-only loading when concentric/eccentric loading is painful. Do this until you can do concentric/eccentric loading without pain.

- Concentric/eccentric loading is more functional than eccentric-only. The goal should be to progress toward full range of motion concentric/eccentric exercises because it will more closely mimic what our bodies experience during climbing.

How long will it take to heal?

This will of course depend on the severity of the initial injury. When minor tendon injuries are rested adequately and return to climbing is managed well, full recovery can occur within 3-4 weeks. Most moderate tendon injuries take 6 weeks for the pain to resolve but be cautious because full tendon healing times will take anywhere from 12 weeks to 6 months. Even if pain has resolved, be cautious about rapidly increasing your training volume or intensity for 12 weeks after the injury.

How do I progress?

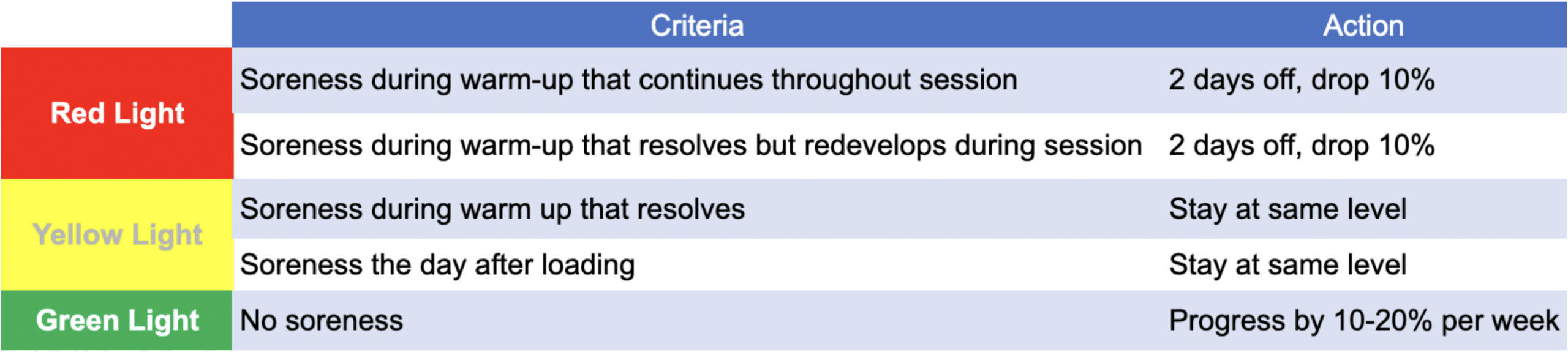

The “soreness rules” are a great way to determine if you should progress, regress, or maintain the same load. Note that “soreness” in this case refers to pain or stiffness or soreness to the tendon that is painful, not to muscle soreness.

What happens if I keep pushing through pain and don’t let my tendon heal?

A tendon that does not get a chance to recover and heal properly is likely going to progress to degenerative tendinopathy. This is when there are significant structural changes to the collagen fibers in the tendon. As the tendon continues to become overloaded your body will lay down type III collagen which closely resembles scar tissue. This type of collagen is weak, does not adapt well to load, and is more likely to be painful and can put the tendon at increased risk of rupture or permanent disfiguring. The road to recovery from degenerative tendinopathy is long and frustrating and not something you want to go through.

Author Bio

Evan Ingerson is a physical therapist and owner of The Climbing Project. He’s a climbing lifer with over 25 years of experience on the wall and 9 years helping climbers get out of pain and back to crushing. He specializes in calling out bad beta—on routes and in training plans. Evan’s here to keep you sending. When he’s not treating tendons, he’s probably hanging on a rope somewhere after falling off his project. Again.

You can get in touch at evan@theclimbingproject.com Check out theclimbingproject.com for additional content.

References

-

Millar NL, Silbernagel KG, Thorborg K, et al. Tendinopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):1.

-

Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(11):887-898

-

Peterson M, Butler S, Eriksson M, Svärdsudd K. A randomized controlled trial of eccentric vs. concentric graded exercise in chronic tennis elbow (Lateral elbow tendinopathy). Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(9):862-872.

-

Stasinopoulos D, Stasinopoulos I. Comparison of effects of eccentric training, eccentric-concentric training, and eccentric-concentric training combined with isometric contraction in the treatment of lateral elbow tendinopathy. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2017;30(1):13-19.

-

Clifford C, Challoumas D, Paul L, Syme G, Millar NL. Effectiveness of isometric exercise in the management of tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1)

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.