SLAP Tears in Rock Climbers’ Shoulder

Introduction

If you’re like me, you’ve gotten all too used to your painful shoulders. Pain is a given in your life now, especially when you climb. Maybe you sometimes get lucky and the pain briefly goes away. But if you climbed hard, pushed yourself hard in the gym, or maybe you didn’t do anything aggravating at all, your shoulder starts aching again. You take a few days off to let your shoulder rest, just like you always do, but days turn to weeks, weeks turn to months, and your shoulder is still hurting. Enough is enough; it’s time to deal with this shoulder pain once and for all, so you can climb at your optimal performance. Physical therapy can help.

Shoulder injuries are common in climbing and compose of about 17% of all climbing injuries.1 An injury called a SLAP tear is the most common type of shoulder injury seen in climbing.2 This article will focus on the anatomy of the SLAP tear, the mechanism of injury, signs and symptoms, and what you can do to manage it.

Anatomy

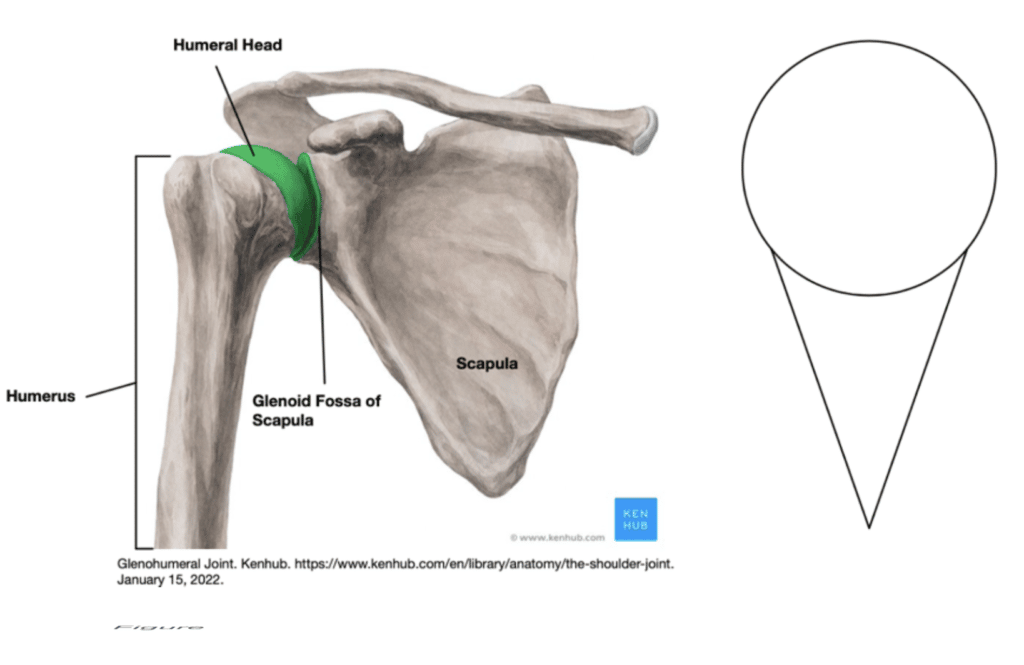

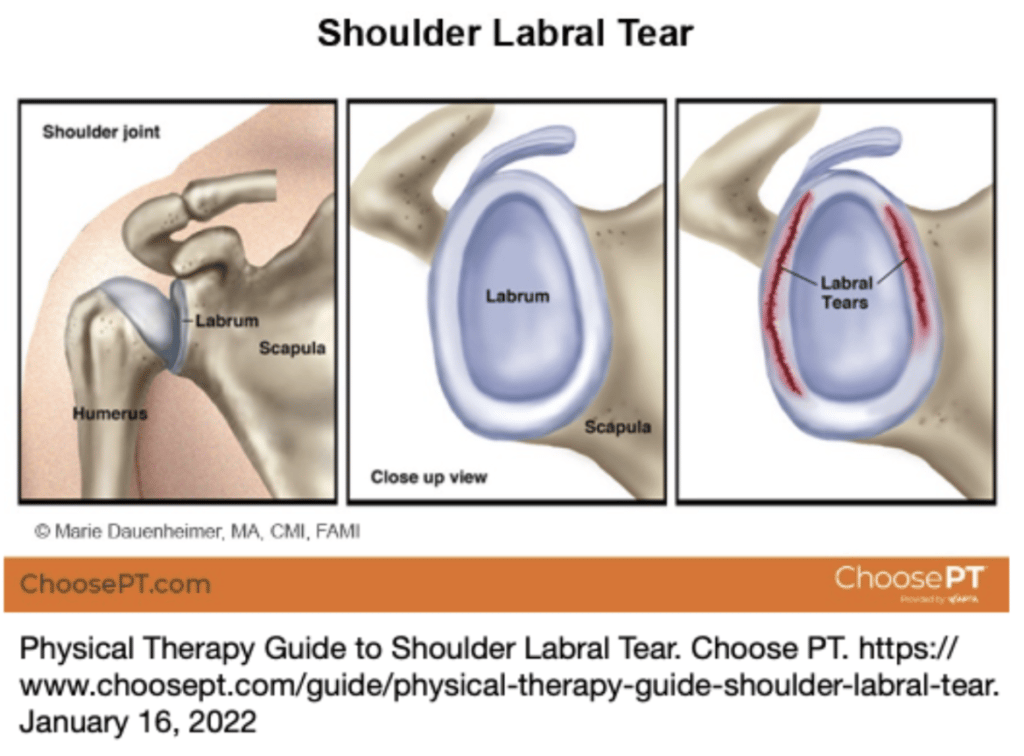

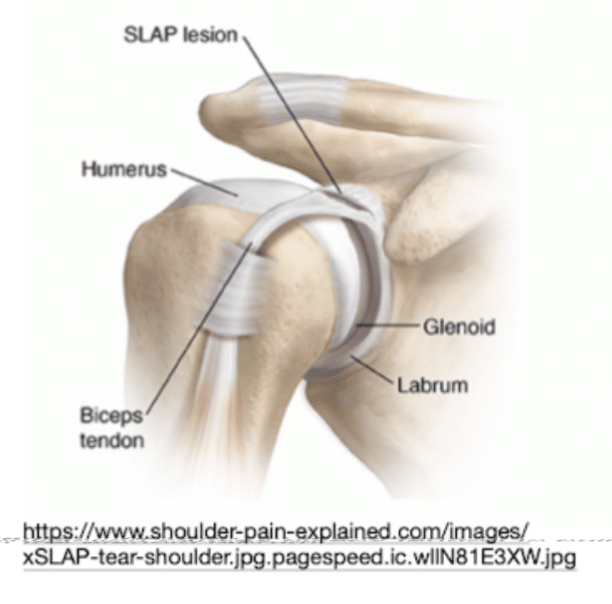

The glenohumeral joint, or shoulder joint, is a ball and socket joint. It is the conjunction between your upper arm bone, called the humerus, and the shoulder blade, called the scapula. The head of the humerus and the glenoid fossa of the scapula join to create the glenohumeral joint. It may be easier to visualize a scoop of ice-cream on an ice-cream cone; the ice-cream represents the humeral head while the cone represents the glenoid fossa.

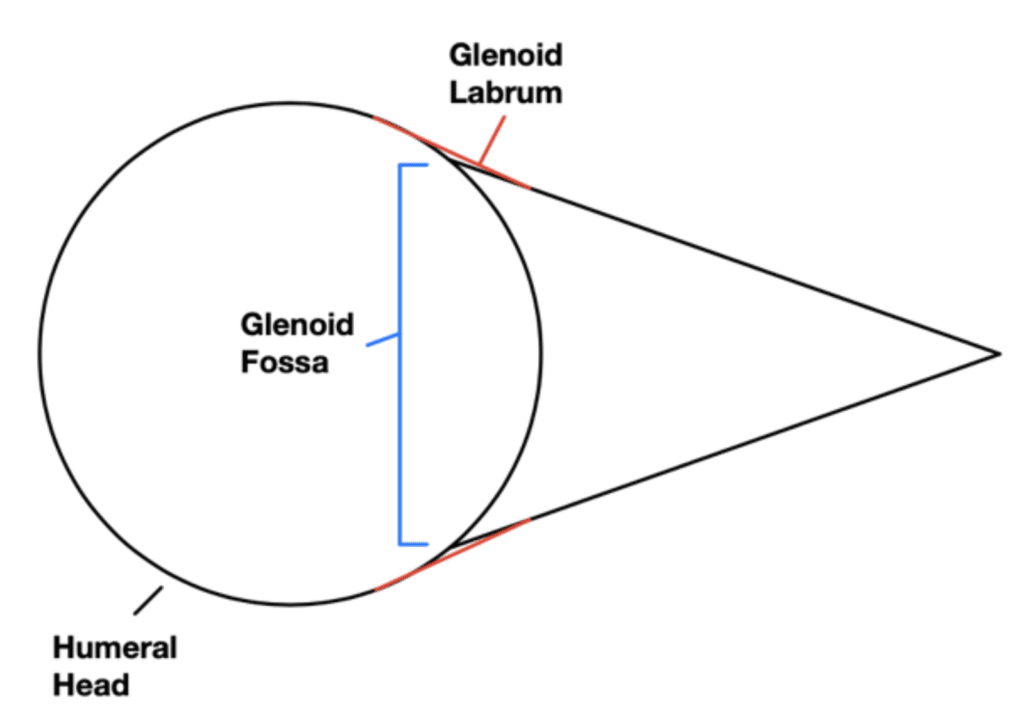

By design, the humeral head is much larger than the glenoid fossa, like a giant scoop of ice-cream on a tiny cone. Just as a giant scoop of ice-cream is unstable on a tiny cone, the glenohumeral joint is much more unstable and more likely to shift around or even separate from the glenoid fossa. There are several anatomical and muscular strategies that our body uses to increase the stability at the glenohumeral joint. Anatomically, the glenoid labrum, a cartilage ring, serves to extend the size of the glenoid fossa to contact more of the humeral head. This is synonymous to using a bigger cone. Given the same sized scoop, a larger cone will allow more stability. Therefore, the glenoid labrum increases the stability at the shoulder and makes it less likely for the humeral head to shift around too much. Important to note is that the long head of the biceps tendon anchors itself on the uppermost part of the glenoid labrum.3

The SLAP tear, or superior labrum anterior posterior tear, most commonly presents as a tear in the upper region of the glenoid labrum such that the biceps tendon anchor is detached from the bony glenoid fossa (ten different variations of SLAP tears have been described in literature).3

Signs and Symptoms

This section will describe the general as well as climbing specific signs and symptoms of SLAP tears that you may be experiencing. However, keep in mind that it is very difficult to diagnose SLAP tears from signs and symptoms alone. If this article gives you reason to suspect you have a SLAP tear, consider seeing a PT for further evaluation.

SLAP tears will commonly, but not always, present with some sort of catching, clicking, or popping sensation in the affected shoulder upon movement, especially in the overhead range. Complaints of pain on the front side of the shoulder associated with a progressive decrease in ability to use that arm are also common. Furthermore, SLAP tears frequently occur with other injuries such as rotator-cuff tears, joint capsule injuries, biceps tendon injuries, and internal impingement; such concomitant injuries may cause night pain, weakness, and a sense of instability.3

What does this mean in terms of climbing? (Need help with literature related to climbing specific symptoms). You may have pain anywhere in your shoulder whenever you reach for a hold. Such pain may be more pronounced when pulling by actively flexing your elbow. This is because when the biceps brachii contracts, the tension is transmitted through the biceps long head tendon and pulls on its origin at the superior labrum to cause pain.3

Mechanism of Injury

- Traumatic pulling injuries

- Example: when you contact a hold after a full send dyno but your body wasn’t ready to catch your weight. Another example is when your feet slip and your arms get forcefully pulled overhead.

- Repetitive overhead pulling

- Example: the wear and tear of your labrum after years and years of climbing with no specific injurious event.

- Pulling with the arm overhead combined with a forceful biceps contraction

- Example: when you catch yourself on holds with your arms overhead and elbows bent similar to the image on the right. The positioning of the shoulder joint, the stress of catching your bodyweight, and the strong muscular force of your biceps transmitted through the biceps long head tendon combine to peel the superior labrum off the glenoid fossa.4

- Falls on an outstretched hand

- Example: when you break a fall with your hands.

Assessment

PTs will proceed with an examination to further discern the likelihood of a SLAP tear. However, there is currently no single or cluster of clinical tests that can identify a SLAP tear with high likelihood. Therefore, a clinical exam for a SLAP tear involves multitudes of tests to increase the likelihood of a SLAP tear.3–5

- O’Brien’s Test (test hand thumb pointing down at shoulder height and in line with the sternum. Use the other hand to pass a 10lb dumbbell into the testing hand. See if there is pain. Then compare symptoms to with palms up).

- Self Speed’s Test (10lb dumbbell in hand, start in full supination with waits in front of shoulders and extend the elbows while maintaining the weights at shoulder height)

- Biceps Load I Test (in supine, shoe-box between head and palm, with shoulder at 90 degrees of abduction slowly ER until feel pain or apprehension. contract biceps to push box into head)

- Biceps Load II Test (in supine place ball or yoga block between head and palm, elbow to the side about 45º above shoulder height, press ball into head and see if pain increases)

The above tests are not definitive in determining the presence of a SLAP tear. But the Biceps Load II test seems to be the most useful single test for identifying a high likelihood of a SLAP tear.6-7

Positive results on the Biceps Load 1 and 2 as well as the Obrien’s test indicate the highest likelihood of a SLAP tear.8

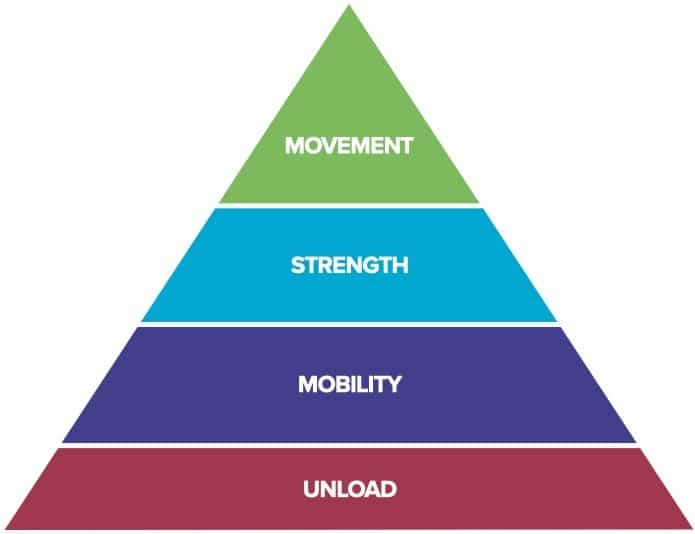

The Rock Rehab Pyramid

Unload exercises:

- Climb with straight elbows

- Climbing with straight elbows will reduce the contraction in the biceps. Since the biceps pull on the glenoid labrum, which causes pain, avoiding biceps contractions will help you minimize shoulder pain.

Mobility Exercises:

- Self Pec STM

- Perform for 3-5 minutes. Repeat as needed throughout the day.

- Foam Roller for Thoracic Extension

- Perform for 3-5 minutes. Repeat as needed throughout the day.

Strength Exercises:

- Standing Rows

- Start with 3 sets of 12 reps with 1 minute rest between sets. Use a resistance that will make performing 12 reps decently challenging.

Movement Exercises:

- Avoid arm dominant climbing

- Try to keep your feet on the wall at all times to reduce the stress on your shoulders.

- Climb more statically

- Dynos are one of the causes of SLAP tears. Find ways to approach a problem or routes more statically.

- Avoid passive dead-hanging

- Passive hanging will transmit your entire body weight through your shoulder. Engaging your scapular muscles will make it easier for your shoulder stabilizing muscles to activate and reduce the stress on the glenoid labrum.

The Research

- Van Middelkoop M, Bruens ML, Coert JH, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Upper Extremity Climbing Injuries in Indoor Climbers. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36(10):837-842. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1547224

- Schöffl V, Popp D, Küpper T, Schöffl I. Injury trends in rock climbers: Evaluation of a case series of 911 injuries between 2009 and 2012. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26(1):62-67. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2014.08.013

- Knesek M, Skendzel JG, Dines JS, Altchek DW, Allen AA, Bedi A. Diagnosis and management of superior labral anterior posterior tears in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):444-460. doi:10.1177/0363546512466067

- Aydin N, Sirin E, Arya A. Superior labrum anterior to posterior lesions of the shoulder: Diagnosis and arthroscopic management. World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):344-350. doi:10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.344

- Abrams GD, Safran MR. Diagnosis and management of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):311-318. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.070458

- Meserve BB, Cleland JA, Boucher TR. A meta-analysis examining clinical test utility for assessing superior labral anterior posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2252-2258. doi:10.1177/0363546508325153

- Cook C, Beaty S, Kissenberth MJ, Siffri P, Pill SG, Hawkins RJ. Diagnostic accuracy of five orthopedic clinical tests for diagnosis of superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2012;21(1):13-22. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.07.012

- Clark RC, Chandler CC, Fuqua AC, Glymph KN, Lambert GC, Rigney KJ. USE of CLINICAL TEST CLUSTERS VERSUS ADVANCED IMAGING STUDIES in the MANAGEMENT of PATIENTS with a SUSPECTED SLAP TEAR. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2019;14(3):345-352. doi:10.26603/ijspt20190345

- Beeler S, Pastor T, Fritz B, Filli L, Schweizer A, Wieser K. Impact of 30 years’ high-level rock climbing on the shoulder: an magnetic resonance imaging study of 31 climbers. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2021;30(9):2022-2031. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2020.12.017

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

If you suspect you have a SLAP tear or you need help managing your shoulder pain, see a Doctor of Physical Therapy. Physical therapy can help you overcome your injuries and maximize your performance.

About The Author

My name is Hiroya Son, I am a 2nd year Doctor of Physical Therapy student at the University of Southern California. I started climbing in 2021. I have been practicing calisthenics for 9 years and have good experience with overhead pulling exercises which has great carry-over to climbing.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.