Rock Climbing Injury Tips: Nerve Mobility

Photo Credit: Eddie Fowke

Nerve Mobility

Imagine that you are belaying your climbing partner and they are stuck at the crux. They keep climbing up and down-climbing but they aren’t going anywhere. You look at your belay device and you see the rope glide back and forth, gaining either more tension or slack.

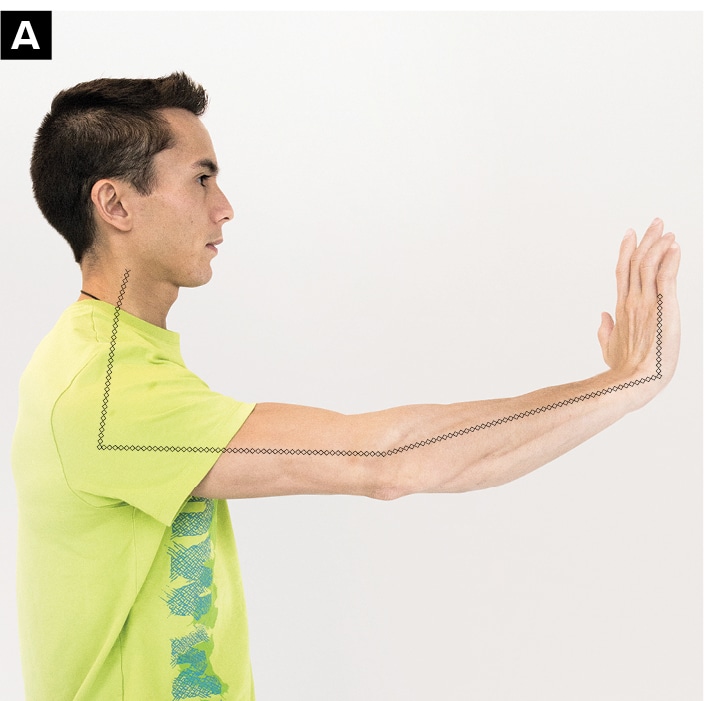

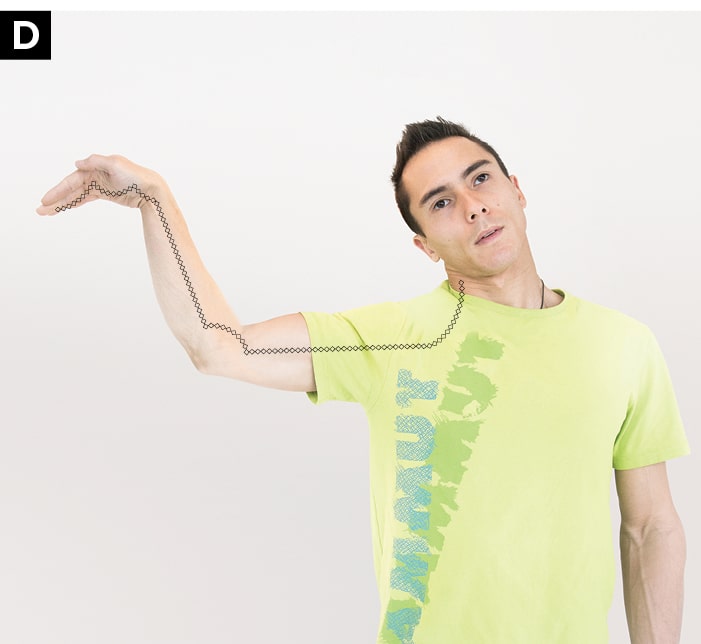

This is how nerves move throughout in your body. They connect from the brain and spinal cord to your muscles. As you move, nerves tension and slacken several millimeters between the layers of muscle. Below is an example of how nerves tension and slacken just like a climbing rope. The curved lines represent slackened nerves while the straight lines represent tensioned nerves.

Photo A: Tensions the median nerve across the elbow, wrist and fingers.

Photo B: Slackens the median nerve across the elbow, wrist and fingers.

Photo C: Tensions the ulnar nerve across the neck, elbow, wrist and fingers.

Photo D: Slackens the ulnar nerve across the neck, elbow, wrist and fingers.

How to Know if a Nerve is Causing Your Pain

One test to identify if you have nerve pain is to put your arm in a nerve-tensioned position (see previous page for examples) and then move your neck. Only perform this test under supervision and clearance from a medical professional as it may cause increased symptoms. Once you are in the nerve-tensioned position, tilt your ear to the same side shoulder and opposite side shoulder. If your symptoms in the arm or hand change with head movement, then your pain is likely related to the nerve, and not the muscles, since there is no single muscle that attaches continuously from the neck down to the arm, wrist hand and fingers. The primary structure that can change tension with head movement is the nerve.

Use Nerve Motion to Treat Pain

You can use the dynamic properties of peripheral nerves to treat nerve related pain from a compressed nerve that is lacking mobility. Since nerves glide several millimeters between interfaces of muscle, you can glide nerves back and forth to increase their excursion and you can tension them to improve their capacity to withstand strain. Just don’t stretch nerves statically like you would stretch a muscle—nerves don’t respond well to sustained stretches. If you stretch a nerve with a sustained hold, the nerve can lose oxygen and blood flow. This can lead to further irritation of the nerve. This is the reason why you can sometimes feel “pins and needles” from a sustained stretch.

Nerve Glide Levels

Since nerves have extra play, they can be tensioned or slackened in different body positions. In this article, you will learn how to glide the median nerve through its respective muscular interfaces. There are two levels of exercise given to mobilize the median nerve. Level 1 is a gentle mobilization that utilizes alternating positions of slack and tension. Level 2 is a stronger mobilization that utilizes mostly tensioned positions.

How to Perform and How Often

All nerve glides should be performed for three sets of up to eight repetitions. Perform daily once you can glide the nerve without pain. The motion should be fluid and rhythmic. Never hold tension for more than two seconds at the end position. Start gently with Level 1 exercises and progress to Level 2 exercises once you can perform Level 1 with ease and no pain. Discontinue nerve glides if you experience an increase in numbness and/or tingling. Nerves are sensitive and the mobilizations described in this article should be performed with care. To explore this topic in more detail, I highly recommend reading the book Neurodynamic Techniques written by the NOI Group.

Watch the videos below as Sean McColl teaches you how to perform a Level 1 and Level 2 median nerve mobility exercise for rock climbing.

Median Nerve Glide Level 1

Median Nerve Glide Level 2

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

Thanks for this article.

When doing these median nerve glides, what are you doing with the thumb? Simple flexion and extension as well?

I have climbing-related nerve feedback in my thumb (thenar?) muscles, which also manifests in my forearm (flexor pollicis longus muscle I think…) and occasionally the wrist. Pinching holds or doing a thumbs-down hand jam seems to make the nerve feedback worse (tingling, heat, sometimes sharp pain, etc.).

Hi Mark,

There is a branch of the median nerve (median recurrent) that innervates several muscles in the thumb (opponens pollicis,abductor pollicis brevis, and superficial part of flexor pollicis brevis). Since several of these muscles are involved in climbing related grips, it could be helpful to involve thumb motion during your nerve mobilizations.

Extend your thumb back to tension the median recurrent nerve

Flex your thumb forward to slacken the median recurrent nerve

You can incorporate this thumb motion during your regular nerve glides.

For example:

Nerve glide 1: Extend your thumb as you extend your wrist, flex your thumb as your flex your wrist

Nerve glide 2: Extend your thumb throughout the entire motion

Thanks for the response. That makes perfect sense, and I’ll give it a shot.

Thank you for this article!

I was wondering if you have any other tips on reducing radial nerve pain aside from the nerve glides listed above. Rest? Ice? Heat?

Thanks in advance for the help,

Eva

The radial nerve can become entrapped in several different regions in the arm. The deep neck (cervical foramen at C6), the superficial neck (anterior and middle scalene), the lower neck (clavicle and 1st rib), the chest (pec minor), the upper arm (triceps), the elbow (radial head and supinator). Addressing where along the chain it is restricted and addressing that area with tissue mobilization may help “free-up” the entrapment prior to nerve gliding.

Hi I am new to climbing I’ve been doing it for about a month indoors and have acquired what feels like nerve pain starting on my right hand just above the wrist and down along my forearm to the left side of my elbow, there is a slight pain in my right shoulder, it goes away when I’m not climbing and starts shortly after I have climbed for a few minutes.

I was wondering what you would recommend for treating this, can I keep climbing? I usually go 3 times a week.

Climbing is great, I have an itch for it but this pain is stunting my progress.

Hi Matt,

One of the more important things to remember about nerves is that they can glide and move through their interfaces. However, entrapments in specific regions can impair this. So mobilizing the tissues in your wrist and shoulder prior to climbing and then performing the nerve mobility exercises outlined in the article can be a good start before getting on the wall. And as with all medical conditions, knowing what is causing the symptoms is key. If you move your neck and your wrist pain changes (on or off) it is likely related to neuro-vascular tissues since there isn’t a single muscle that continuously spans that region.