Pocket Change – Adapting the Way You Pull on Pockets

I recently finished the classroom portion of my Doctor of Physical Therapy education, and I am now moving into my final clinical rotation down in San Diego. With a short break in between school and clinic, I took a trip with my girlfriend to Ten Sleep Canyon in Wyoming. The limestone there is incredible! I had never climbed on such pristine, consistent limestone before, and it certainly wet my whistle for trips to famous limestone crags like Céüse in France (Céüse on Mountain Project.) Like most bulletproof limestone crags, the rock is mottled with pockets galore. Along with this abundant array of tiny finger holds comes a potential for injury if the pockets are not utilized safely. If you’ve climbed on pockets, then I’m sure you’ve tested your luck with putting two fingers in a pocket, or even tried out a daring one-finger pocket (mono). In this post I’d like to touch on the common techniques for pocket climbing, and educate you on the proper method to avoid injury. My trip to Ten Sleep Canyon inspired this blog post, so I hope you can take away a helpful message, and climb strong and healthy on your own trip to a pocketed limestone crag!

Anatomy:

Muscle to Tendon Ratio

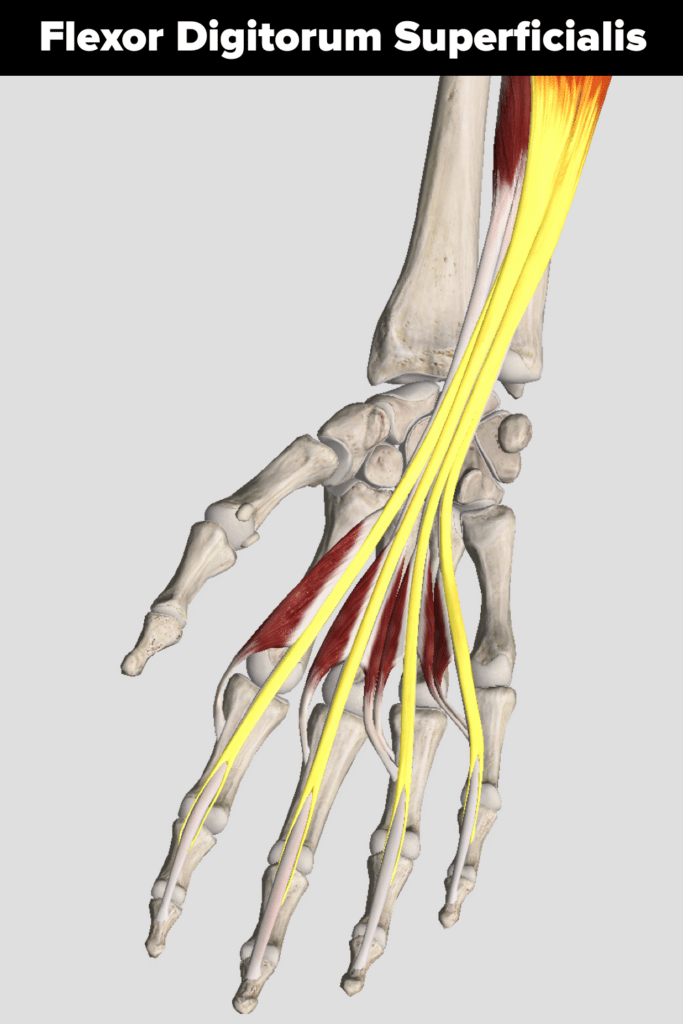

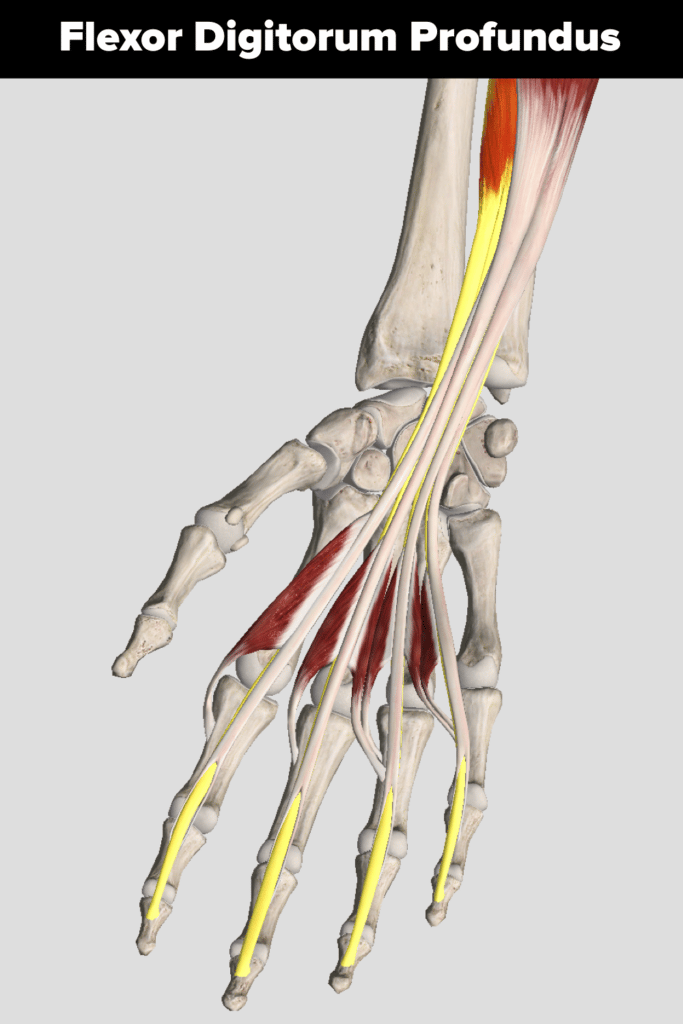

You may remember from my Pulley Injury article that you have two main muscles in your forearm that flex your fingers. These muscles are the Flexor Digitorum Superficialis and Profundus (FDS and FDP respectively). The unique situation posed here relates to the muscle to tendon ratio. Each of these muscles have 4 tendons, each going to one respective finger (index, middle, ring and pinky fingers). What this means for you is that when you want to flex some fingers but extend others (like when climbing in pockets), this introduces an opposing strain for the muscle. I’ll explain the safer alternative in another section.

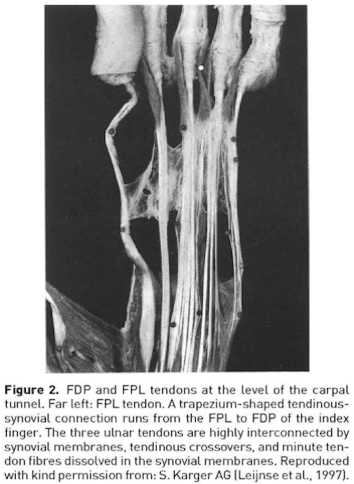

Tendon-Tendon Connectivity

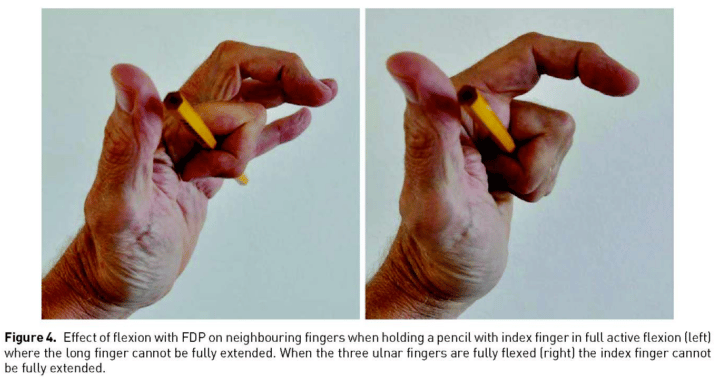

Another anatomical consideration I’d like to point out is related to the more specific tendon-tendon connectivity that often gets overlooked. At the level of the carpal tunnel, our FDP tendons are significantly interconnected.1 Leijnse et al.2 pointed out the “fibrous connections between the FDP tendons at the wrist level, which consist of strong tendinous or fascia-like structures.” This adherence affects the mobility of each individual finger flexor tendon with respect to each other. In more simple terms, when you want to flex or extend one individual finger, this affects the other fingers and vice versa. Because of this interconnectedness, you need to respect the anatomy and use safe pulling methods. Refer to this image to help wrap your head around the content.

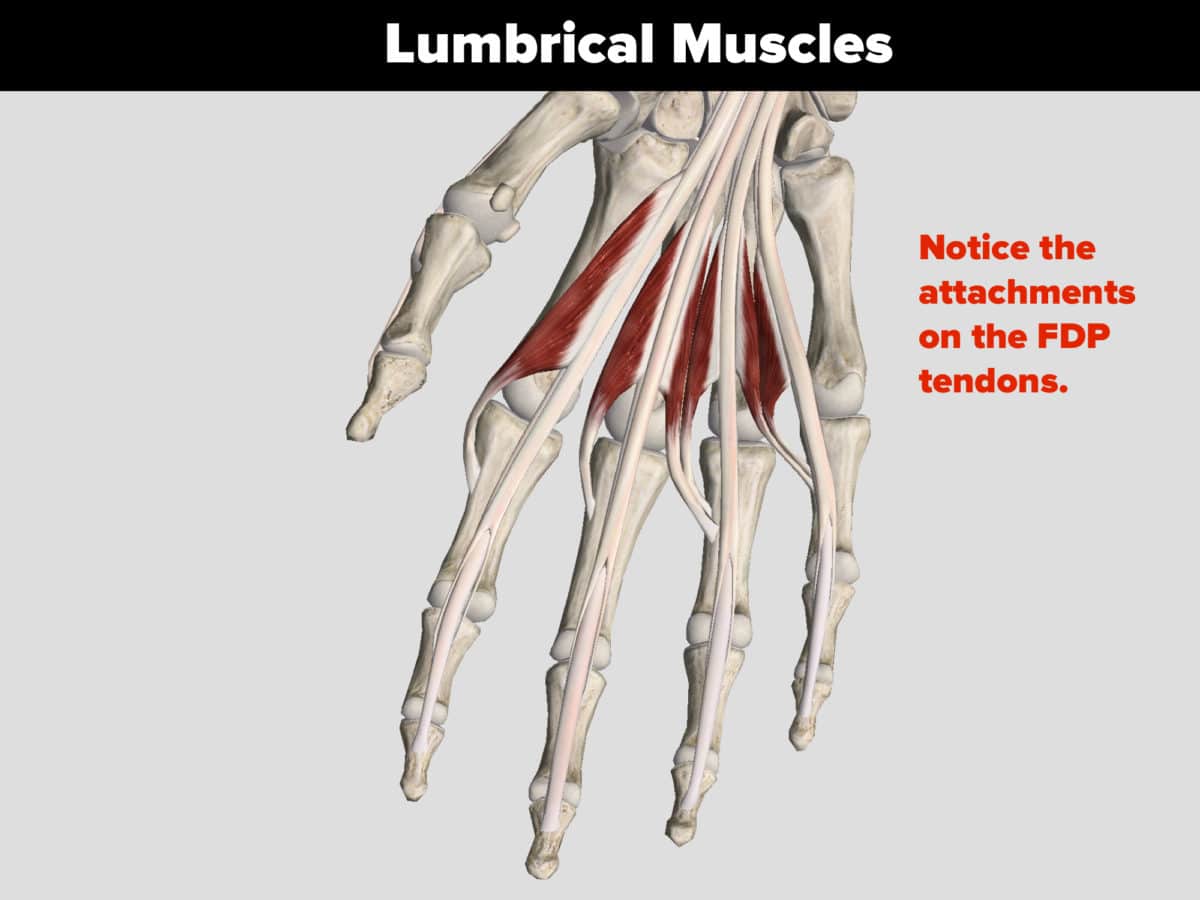

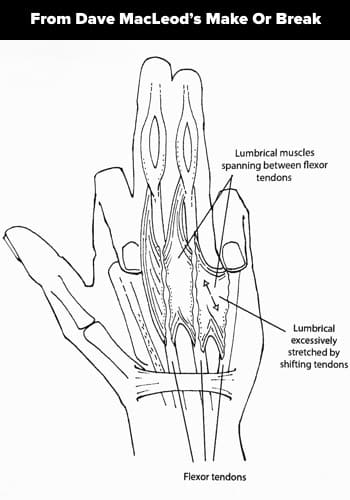

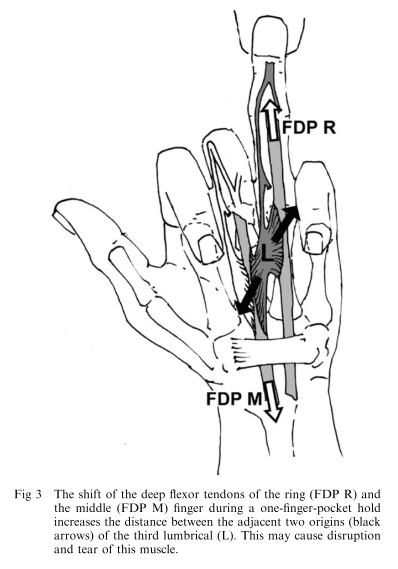

Lumbricals (Intrinsic Hand Muscles)

The final anatomy note I want to point out is regarding the lumbrical muscles in your hand. These muscles work to flex your fingers at the hand (at the metacarpophalangeal, MCP, joint), and also work to extend your fingers by pulling on the extensor hoods. The unique aspect of these muscles is that they originate from the FDP tendons, and not bone like most other muscles. With muscles attaching to moveable tendons, this may lead to complications when motion is in opposition (flexion vs. extension) as mentioned above. More on this shortly.

The Quadriga Effect:

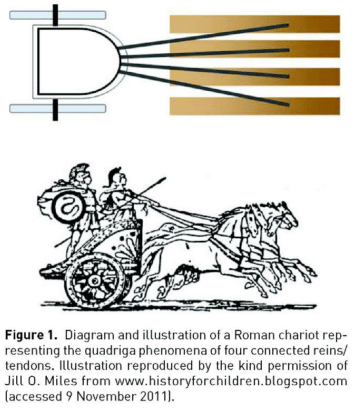

The first two anatomical concepts explained above lead to what has been described as the quadriga phenomenon.1,3 Dr. Verdan first described it in 1960 and Ton Schreuders, a physical therapist from the Netherlands, elaborated on the phenomenon in his own article more recently. A quadriga is a Roman chariot pulled by four horses, and the four reins of the horse-chariot system are described to resemble the finger flexor tendons (see image below.) In Dr. Verdan’s words, the quadriga syndrome is “a condition in which the flexor tendon excursion is reduced in an unaffected finger when the excursion of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon of the adjacent finger is altered by stiffness, injury, or adhesion.” Because of the interconnectedness of the FDP tendons, restriction in one finger will affect the others. Similarly, when you climb in a mono pocket, your one finger is extended in relation to the other fingers and these strained connections may result in injury. Even though you have individually moveable fingers, they are still connected and influence each other’s movement.

To help drive the point home, try out this exercise demonstrating the restrictions caused by our finger tendon connections.

Commonly Seen Pocket Climbing Technique:

Very commonly, climbers use an opposing flexion/extension finger posture when pulling on pockets. The holding finger’s proximal phalanx is in relative extension compared to the adjacent fingers’ phalanges, which are in relative flexion (see images below.) There is a reason for this. The quadriga effect explained above3,4 helps to increase your pulling power by roughly 48% as described by Schweizer in his 2001 article.5 But just because you are stronger using this posture doesn’t mean that you should always use it, especially if it adds a potential for injury. In the next section are some potential injuries resulting from this common pocket finger posture (oppositely flexed/extended fingers), and in a later section I’ll suggest a safer way to hold pockets.

Where Potential Injury May Arise:

When injury occurs during pocket climbing, we generally see three areas affected:

- At the muscle belly where the individual tendons differentiate into their respective muscle fibers.

- At the lumbrical muscles in the hand, known as Lumbrical Shift Syndrome.

- At the tendons themselves.

Forearm Muscle Strain:

Remember that the FDS and FDP muscles each have 4 tendons that course through to each finger from one muscle belly. Different muscle fibers within the muscle belly control respective finger tendons but still perform as one muscle. With this configuration, your muscle may be prone to strain when one finger or some fingers are extended and others are flexed. This opposition can cause conflicting force internally at the muscle, and lead to a muscle strain. Think of it like a leather glove, where the body of the glove is the muscle belly, and the fingers are the tendons. If you pull on one of the fingers (representing a finger in a mono pocket) and pull down on the opposite corner of the glove (representing the muscle fibers dedicated to another finger contracting and opposing the pull of the mono pocket), you can see tension built up in the leather. This represents the internal conflicting strain in the muscle belly, and could lead to a muscle strain injury.

Lumbrical Shift Syndrome:

In extreme cases, usually when pulling on a one-finger pocket, an injury to the lumbricals may occur. Because the lumbrical muscles attach to the FDP tendons, a shearing force presents itself when you oppositely extend and flex adjacent fingers. When the finger/s are holding the pocket, they are extended and this tendon has a relative upward pull due to tension from the mono pocket. If you are flexing your adjacent fingers, these tendons have a downward force, opposing the pocketed finger/s. Due to the muscle attachments, this applies a shear force to the lumbrical, and may lead to a strain or tear. Look at these images to better understand the shear forces described.

Tendon Injury:

This is a more straightforward injury to explain because it’s directly related to the inherent strength of a tendon. If you are pulling on a mono pocket, you only have one finger loaded. If the force you’re pulling with exceeds the strength of the tendon itself, this could result in a sprain or rupture of that tendon. These injuries are not as common, but the potential is there. Usually the injury occurs as a muscle strain in the FDP, FDS, or lumbricals.

Recommended Hand/Finger Posture for Pocket Climbing:

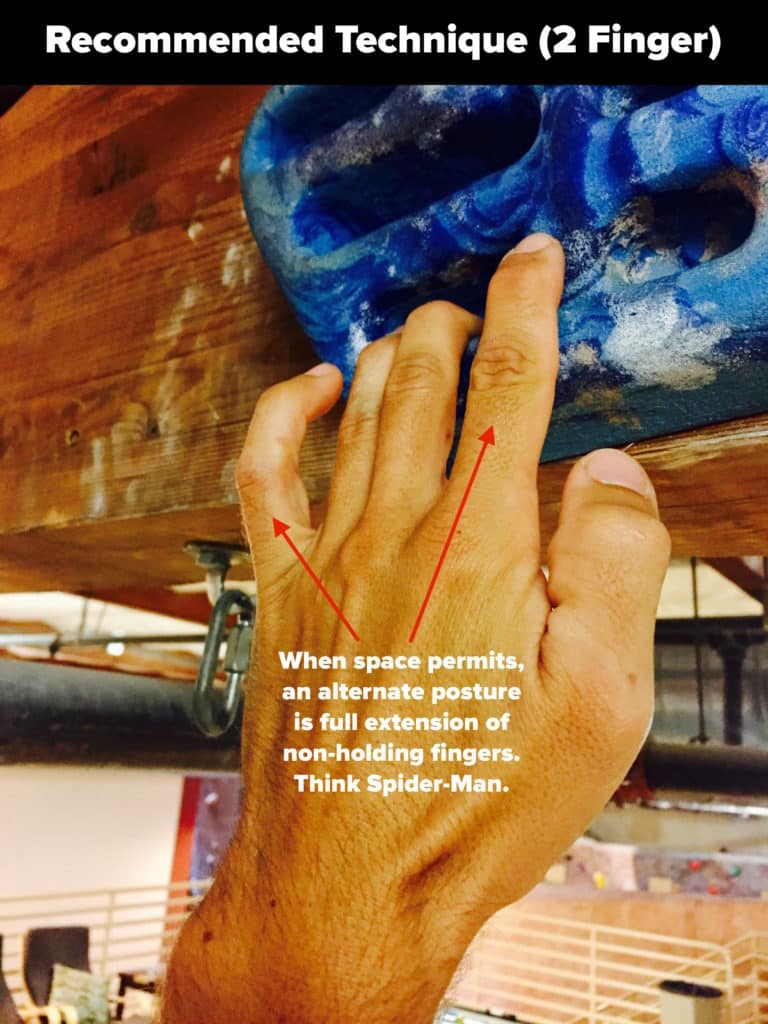

So how should you safely position your fingers when climbing in pocketed limestone? Let’s ask our friendly neighborhood Spider-Man (see image below.) Think about his hand/finger posture when he’s shooting his webs. The fingers that are not actively squeezing his web shooters (analogous to the climber’s fingers that are not in the pocket) are neutral/extended and NOT flexed. Now, I will admit that Spider-Man gets a little carried away with his other fingers (the ones that would be in the pocket), and he is not a perfect analogy for pocket climbing. But the main idea is to avoid oppositely flexing/extending your proximal phalanges. Ideally when climbing, all your proximal phalanges should be in line with each other. Using what you learned above, think about how this new posture will reduce your risk of injury. There is no opposing flexion/extension force at the hand or finger. This eliminates the shear forces at the lumbricals and reduces the strain of the flexor muscles.

My reasoning for bringing up Spider-Man is to leave you with an image you can remember when thinking about how to safely pull on pockets. Not exactly his hand posture, but all proximal phalanges in line. When in doubt, shoot your web! Refer to the images here explaining the proper technique.

Main Take-Away:

When climbing in pockets, protect yourself from injury by utilizing proper finger/hand posture. Yes we may be slightly stronger when we flex the adjacent fingers, but only at the risk of injury. Keep all of your proximal phalanges in line with each other to avoid unnecessary shear forces. Strengthen your arms, hands, and fingers in this new posture to ensure you’ll have the strength necessary to send your project while protecting your body from injury.

VS

Author Bio:

Matt is a 3rd year Doctor of Physical Therapy student at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. He lives in Boulder, CO to be closer to his playground. This is his final semester of the DPT program and he is undertaking an independent study researching climbing injuries and injury prevention techniques to provide to his clients. His main interests are in sports medicine physical therapy and injury prevention revolving around the climbing athlete. Before starting school, Matt lived in San Diego, CA and worked at Mesa Rim Climbing and Fitness. After graduating from his DPT program, he plans to return to San Diego and work alongside Mesa Rim to give back to the community he loves.

Matt predominantly climbs sport at the 5.12c/d level, and has recently taken up the craft of trad climbing. He has been climbing since 2008. Matt empowers people to take their health into their own hands, and guide them toward a stronger, injury-free climbing lifestyle. He currently teaches injury prevention classes at local climbing gyms, and also provides content about the topic on his Instagram (@theclimbingpt).

When Matt isn’t climbing, you can find him adventuring somewhere in the wild. He is also an avid biker. He rides BMX, downhill mountain biking, and has completed a tour cycling trip around New Zealand. He connects with anyone in the extreme sports realm as a healthcare provider who has the capacity to understand their sport and assist them with their unique needs.

Follow Matt:

Instagram: @theclimbingpt (https://www.instagram.com/theclimbingpt/) //

@basebklyn1 (https://www.instagram.com/basebklyn1/)

Contact Matt:

Email: mattdestefanopt@gmail.com

References:

- Schreuders TAR. JHS(E) The quadriga phenomenon: A review and clinical relevance. J Hand Surg Am. (0):1-10. doi:10.1.

- Leijnse JN, Bonte JE, Landsmeer JM, Kalker JJ, Van der Meulen JC, Snijders CJ. Biomechanics of the finger with anatomical restrictions–the significance for the exercising hand of the musician. J Biomech. 1992;25(11):1253-1264.

- Verdan C. Syndrome of the quadriga. Surg Clin North Am. 1960;40:425-426.

- Verdan C, Poulenas I. [Anatomic and functional relations between the tendons of the long palmar muscle and the long flexor muscle of the thumb at their crossing in the carpus]. Ann Chir Plast. 1975;20(2):191-196.

- Schweizer A. Biomechanical properties of the crimp grip position in rock climbers. J Biomech. 2001;34:217-223.

- MacLeod D (Mountaineer). Make or Break : Don’t Let Climbing Injuries Dictate Your Success.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

Hi – What do you do if you feel pain in your lumbrical muscles. My pain is after I worked out on some pockets and then did another hard session the next day. After the following morning I woke up and noticed my hands were tender on my palm side between/below the two knuckles when i press into them.

Hi Luke. Thanks for your question and I’m sorry to hear you have pain in your hand. Because you are describing lumbrical pain, and you are training on pockets, I think the most important thing to do is stop hanging in the pockets until you have eliminated the pain. Sounds obvious but I want to ensure we are both on the same page. You most likely strained the lumbrical during a situation called “lumbrical shift.” During the time away from training pockets (maybe 1-2 weeks), make sure you are massaging the injured area to promote blood flow and performing gentle active range of motion of the hand. If you do not have pain with jugs, crimps, or other climbing, then you may gently resume climbing but be honest with your body and don’t climb through any pain. When the lumbrical pain subsides, begin pocket training again but lighten your intensity. This is easily done using a pulley system to offload your body weight. Most of us can’t handle full body weight pocket hangs right out of the gate, so your body needs time to adapt to the stimulus. This can take months to years depending on how long you have been climbing for. Also, make sure you’re using the finger postures explained in the article as much as possible. I know it’s unrealistic to do it all the time, but when training try to focus on form. For more info about the offloading of weight using pulleys, check out the pulley injury part 2 article. Hope this helps! -Matt DeStefano

Hello!

I recently strained my left hand forearm muscle for the third time in a year. Is there any recovery steps and preventative strengthening/ stretching I can do in addition to the new “spider man” way of holding pockets?

Hi Almar. I’m sorry to hear about your injury. In response to your question, initially you will want to massage the muscle frequently to break up any scar tissue in the area, and also to promote blood flow. You also want to ensure that you are actively moving the muscle/fingers, but not loading them initially. That comes later. Just go through an active range of motion at first. Once you are pain-free, you can begin gently loading the muscle, but make sure it’s not painful. Gentle stretching to the muscle will also be important along with your massage, initially, and also throughout your life. Stretching is always and integral part of any sport. Finally, the “spider-man” technique is an excellent way to avoid injury, so definitely stay on top of that. I would also highly recommend working on your footwork as a climber. I don’t know how you injured yourself those three times, but often it is because we slip a foot, and shock load that hand/fingers. This creates an incredible amount of force straight to the muscle unit. Make sure when you’re climbing that you’re focused on proper foot placement. I hope this helps! I know it’s not much, but there’s only so much I can do via internet comments ;)

Sincerely,

Matt

Hey Matt, great article!

I hurt myself pulling on a two finger pocket (middle and ring finger) and the pain is quite strange… when I pull on my injured ring finger (in an open hand position) it seems that my tendon is hurting: starting from the hand to the wrist and especially by the anterior side of my elbow. Do you think that stained my tendon? Or is it tendinitis? Or did I strain all the muscles involved? What should I do to recover?

I feel no pain crimping though…

Thank you for your advices!

Sincerely

Romain

Response from The Climbing Doctor, Dr. Jared Vagy DPT:

If pain extends from the tip of the finger to the inside or front of the elbow and it was injured with a single mechanism (an instant in time), it is likely a flexor tendon strain of either the Flexor Digitorum Superficialis or Flexor Digitorum Profundus. See the diagnostic process in my comment to Rowan to determine which tendon was most affected.

Hi Matt,

Thanks very much for your article, I think it’s the first accurate description I’ve read of my own injury. At the risk of asking you to describe the best rehab procedure for the third injury related to poor pocket technique, I believe I injured my flexor tendon (not ruptured but definitely strained) on an undercling pocket.

I’ve taken 2 weeks of rest and a lot of the pain has subsided (it was never particularly acute to begin with), although I do sense some tenderness, particularly when the pinky is curled towards the palm as you describe. What would you recommend I do to (safely) return to strength?

Many thanks for your help!

Response from The Climbing Doctor, Dr. Jared Vagy DPT:

There is a 4 step process to return full back to climbing.

1: Unload the affected tissue

2. Improve mobility

3. Increase strength

4. Restore optimal movement

I would reference the Pulley Injuries Explained Part 2 article with the adjustments of making sure to perform lumbrical stretching and lumbrical tendon glides (2. improve mobility) isometric lumbrical strength (3. increase strength) and then apply the movement tips from this article (4. restore optimal movement)

Hello,

I’ve just injured something by pulling on a middle finger 1 pad mono pocket exactly as you advised not to. However, I’m unsure whether I’ve damaged the tendon on a lumbrical muscle. There is no tenderness when pressing on the hand or finger, and the pain is only felt when there is opposition between extension and flexion in middle and ring fingers respectively. I can’t pinpoint the location of the pain, it feels like the middle finger all the way from wrist to tip.

I can hold a 2-finger pocket with my middle and ring fingers, even with bad posture, with almost no pain, but can’t load a pocket with index and middle fingers, or hold a middle finger mono whatsoever. I can hold crimpy edges fine.

A response would be so much appreciated.

Thanks,

Rowan

Response from The Climbing Doctor, Dr. Jared Vagy DPT:

Below is a differential diagnostic process that climber can use to determine which structure in their hand or finger is most affected. It involves load testing the finger to differentiate between a lumbrical strain, FDS tenosynovitis, FDP tenosynovitis and dorsal interosseous strain.

Lumbrical: Muscle testing the lumbrical (MCP flexed, IP’s extended) generates symptoms, symptoms are mostly local to the palm with some symptoms into the base of the digit, increased symptoms with single middle finger kettlebell hold when the opposing fingers are actively flexed, weakness into lumbrical tendon glides

Flexor Digitorum Superficialis: Hanging a load at the middle phalanx generates pain (sling with weight), hanboarding with pressure into the middle phalanx or muscle testing generates symptoms, flexing the DIP while hangboaring reduces symptoms, flexing or extending the wrist while palpating the tendon alters symptoms, weakness with crimping

Flexor Digitorum Profundus: Hanging a load at the distal phalanx generates pain (sling with weight), hanboarding with pressure into the distal phalanx or muscle testing generates symptoms, flexing the DIP while hangboaring increases symptoms, flexing or extending the wrist while palpating the tendon alters symptoms, weakness with crimping

Dorsal interosseous: increased pain during palpation when fingers are spread activity versus relaxed inward, weakness into spreading the fingers

Hello,

Yesterday while climbing I used the wrong technique you described above while pulling a 2 finger pocket (ring and middle finger) and felt a dull pop. Initial feeling was a tingling sensation and moderate, dull pain radiating from the base of the ring finger to the fingertip and up into my forearm. The pain went away after a few minutes but acted up in certain hand/finger positions.

Today I have soreness and tightness in the same areas as during the initial pop, but the pain/discomfort symptoms are most noticeable at the ring finger MCP and in my palm near the MCP between ring and middle fingers, with some swelling in the center of my palm.

Going through the diagnostic process points me towards an injury to the FDP, but I’m worried the “pop” I felt, since that is common with pulley injuries.

Should I be worried even if the pulley isn’t tender to the touch or painful while crimping? Did I injure the tendon itself and not just strain the muscle? Is there any hope left for my plans to go on a month long climbing trip this May?

Thanks,

Kent

Hi Kent,

I’m sorry to hear about your injury. From what you’ve described it sounds more likely that you may have injured your lumbrical muscle that lies in between your 3rd and 4th metacarpals. This would explain the swelling in the center of your palm. You may have also strained your flexor tendon (hard to tell which one FDP/FDS without hands on) due to the discomfort up your forearm. Regarding your trip planned, there are a few other things that need to be clarified and this platform is not the place to discuss such issues. I can offer you more assistance via a video call if you would like. You can email me at mattdestefanopt@gmail.com. Hope this helps.

Sincerely,

Matt

Hello,

Thanks for putting all this work into the article, it was super informative and great to get to know how stuff works in my hands a bit more. I shock loaded my tendon/muscle in my ring finger yesterday with my front 3 open handed and my pinky folded down. Based on what you commented above, it seems like it was my Flexor Digitorum Profundus that was strained and the pain is maybe about an inch or so below my wrist.

Do you have any rough idea on how long of a recovery a muscle strain like this may be? I see above that you recommed massaging the site or soreness and offloading it for a little while and doing some mobility exercises. As far as getting it back up to 100% in strength, do you recommend buddy taping my ring and pinky fingers together to make sure the proximal phalanxs are aligned and progressively increasing the load or should I also do some lower weight with the two fingers opposing each other since that was how it was injured and how the symptoms are reproduced? Is there any benefit to that and would it help speed up the recovery process?

Thanks so much for all you do!

Hi Nick,

It looks like by having your pinky folded down and shock loading your hand that you may have injured the FDS or FDP muscle (depending how deep the pocket was). Tendon injuries are complex and the recommended healing times vary based on the severity of injury. With that being said, with a low grade strain, a climber can return to climbing within a matter of a few days, while a higher grade strain can take weeks or months.

But when returning back to climbing, the structure of the program is similar to that of the article. Unload, mobilize, strengthen and return to movement. In order to minimize the load, avoiding differentiating your fingers (dropping your pinky) on challenging routes, but you can progressively strengthen back into that position within tolerance. I am not a big fan of buddy tapping, but if you are missing climbing and need to get back at it, it may minimize strain on the potentially injured flexor tendon. Best of luck!

Hi,

I injured my left ring finger exactly holding a pocket on a board as you described in the article (not using the spiderman move) hearing a pop. What do you think is?

I did a month of rest from climbing but i feel sometimes that the fingers are not like the others of the right hand. What do you suggest ? are there some exercise I can do in order to recover faster or do i have to wait?

thank you

Giorgio

My first piece of advice would be to have it checked out by a doctor of physical therapy so that they can properly diagnose between a lumbrical strain, pulley sprain, or any other conditions in the finger/hand. If a lumbrical strain, you can follow the protocol outlined in the article below:

Schweizer, A. (2003). Lumbrical tears in rock climbers. Journal of hand surgery, 28(2), 187-189.

It was a case series of climbers with the same pain and mechanism of injury of the ring finger (pulling on one finger pocket). A tear of the lumbrical tear was detected by ultrasound examination. They were told to avoid one-finger-pockets, stretch the lumbricals – intrinsic minus or alternate flexion and extension of ring and middle finger. The pain disappeared after 6-10 weeks.Exercises on one-finger-pockets were started after 2-4 months.

This article sounds like it describes my mechanism of injury but I cant figure out where the tear is specifically. I was hanging from a pocket by my index and ring, leaving the middle finger flexed downward. It was a weird hold and I immediately regretted it! No pop, no swelling, full ROM, but something was tweaked. Best description is pain at the DIP joint on middle finger (the flexed one), when the ring finger is weighted (holding groceries). Love to get thoughts on how to tape and rehab since this doesn’t appear to fit neatly into A2/A4. I’ve taken 4 or 5 days off and want to get back on the wall gently as soon as I can

Since the lumbrical originate form the FDP muscle, lumbrical tears can also manifest as finger and forearm pain. The FDP is the main muscle that flexes the DIP joint. So this may be the reason that weighting the ring finger holding groceries with the DIP flexes may be causing symptoms. If the pain extends into the fingers, it is unlikely that a lumbrical tear is the primary diagnosis since the muscle attaches to the base of the proximal phalanx and does not extend past that.