Physiology of “Forearm Pump” and Ways to Delay it’s Onset

When you think about finally sending that project you’ve been working on, or climbing harder/longer routes what’s the biggest thing stopping you? Some may say it’s grip strength, upper body strength, or just fear. However, everyone can agree that decreased endurance and getting that dreaded “forearm pump” is one of the reasons you have to stop climbing. In general, this pump stems from an increased demand on the small muscles of the forearm that cause your fingers to close (finger flexors) which in turn increases blood flow to your forearms. But what else is going on, are there ways to recover quickly, and how do you train to have a later onset of “forearm pump”?

What is a Forearm Pump?

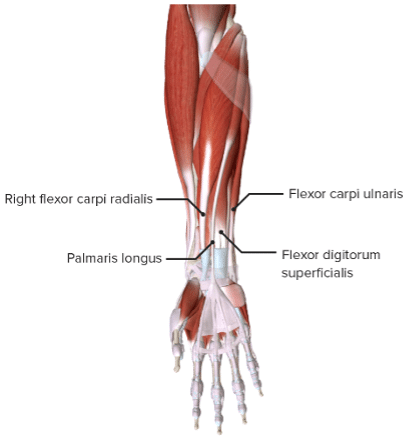

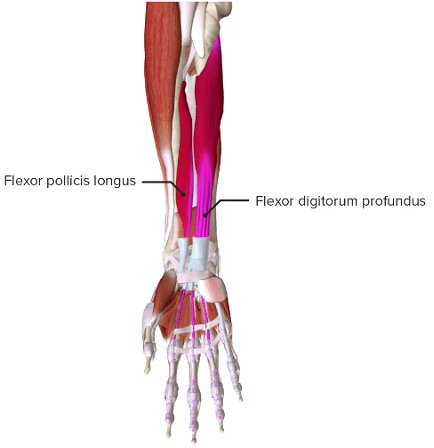

Rock climbing involves using the entire body with precision, and our fingers have the burden of holding our body with relatively small muscles. There are superficial and deep finger flexors located on the palmar side of our forearms, most of them originating at the medial epicondyle of the humerus (funny bone).

Signs of a muscle pump are straightforward; decreased grip strength, decreased contraction velocity, decreased finger/wrist range of motion, and the feeling of fullness or “pump” in the forearm. The forearm pump is essentially muscular fatigue of the the finger flexor muscles. These symptoms are caused by a combination of factors, such as an increase in blood lactate levels, an increase in blood flow to the area, and an increase in blood retention in the forearms.5,6

Our hands perform repeated bouts of isometric contractions during climbing, which means that the muscles are not lengthening or shortening but holding a static position. Isometric contractions result in accumulation of lactate since the muscle isn’t stretching and shortening with enough force to create a natural pump for blood to flow in and out, and therefore flush lactate and other metabolites into the body’s circulatory system.6

A buildup of blood lactate creates the “burning” feeling in the muscles when exercising. Voluntary contractions of the forearm muscles causes an increase in the mean arterial blood pressure, which decreases blood flow to the area and leads to increased fatigue.6

Why are elite rock climbers able to climb harder and longer than beginner climbers?

Research shows that they have a significantly higher strength-to-weight ratio and de-oxygenated the flexor digitorum profundus (finger flexor) much more and at a greater rate compared to beginner climbers.5

This means that advanced & elite climbers were absorbing more oxygen into their muscles when isometrically contracting them, suggesting an increase in capillary density and an enhanced capability to absorb oxygen into their working forearm muscles. These physiologic changes are not inherent, they are characteristics that can be trained over time. This means that all climbers can train to increase their finger muscular endurance and capillar density to delay the forearm pump!

Treatment/training

Current research supports the use of active recovery as a means of reducing blood lactate levels, however in the trials performed, active recovery involved either brisk walking or using a stationary bike. While these methods don’t help during a quick rest in between holds, performing active recovery in between climbs is a great way to decrease the forearm pump. There are some popular methods of quick recovery during a climb, such as shaking the arms out overhead, below the heart, or even a specific prescription of both for a certain time (G-Tox). G-Tox is a method created by climber and author Eric Horst that calls for alternating the arm position above the head for 5-10 seconds while shaking, then hanging the arm downward while shaking 5-10 seconds. You alternate back and forth for 2 minutes. The article suggests that the climbers who did the G-Tox had an increase in hand grip strength by 18.4% and a decrease in blood lactate concentration.3

However, the graphics from the study are only available on a climbing website, which leaves out a lot of crucial information such as sample size, participant demographics/climbing skill, methods, procedures, statistical analysis, and discussion. The placebo effect is very powerful, so trying this method could possibly lead to some positive results. If Adam Ondra shakes his arms out, there’s probably no harm in trying it.

With that said, one thing that has been researched is increasing endurance for climbing to delay the forearm pump. Here are some ways to train increasing endurance:

For Beginners: One way to delay the onset of the forearm pump is by climbing with proper and efficient technique.

- Climbing with sloppy footwork (thus relying on arms/fingers more), over gripping, and climbing with bent arms can lead to an increased demand on the finger flexors when the legs could be taking over that work.

- Climbing routes back to back can be taxing on the forearms and hands when you haven’t worked up the endurace for that yet. Taking frequent breaks between tries is an easy way to delay the onset of forearm pump.

- If you boulder a lot, switching it up and top roping can be a good change for longer duration climbing and to increase your stamina/endurance.

- Training for endurance really comes down to spending time on the wall, tidying up footwork and technique.

For intermediate/advanced climbers: Training towards increasing capillary density in the forearms and building endurance will lead to increasing the arms’ ability to deoxygenate key muscles needed for climbing. Some general endurance training routines include:

- ARC (aerobic restoration and capillarity) Training- This one has general recommendations that must be tailored to the climber who is training. Essentially, you want to climb continuously for 20-45 minutes without getting a big pump, just a mild one. Can be performed 2-3 x/week, but make sure to work up to this intensity! This is a good exercise for climbers of all levels, since you can adjust your intensity based on how much of a pump you get.7

- It can be done on a bouldering wall, doing routes that are 1-2 grades below the climber’s limit.

- It can also be done with auto belays, climbing up and then downclimbing routes 1-2 grades below the climber’s onsight limit.

- 4×4- this type of training has been around for a long time and has a lot of room for variability depending on climbing experience and climber rating.8

- For climbers under 5.11d:

- Warm-up 20 minutes at an easy level

- Practice some boulder problems that will be used in the drill, a grade that can be flashed

- Choose 4 boulder problems (ideally ones with a lot of movements), and start with the most difficult/steepest first and ending with the easiest. So for example, someone who flashes a V4 does V4, V4, V3, V3.

- Climb all the problems back to back with no rest and record the time taken to climb all of them. Rest for twice the amount of time it took to climb them.

- Repeat 4 times. Rest for around 15 minutes and repeat until 25% of the attempted problems are failed.

- Hangboarding- a study found that intermittent dead hangs using a half crimp grip on a 15 mm edge improved strength and endurance tests by 45% after 8 weeks of training.4 Hangboarding is better for intermediate to advanced climbers (the study looked at climbers who climbed >7a or 5.11d).

- 3-5 sets of 4 ten-second reps.

- 5 second rest between reps and 1 minute rest between sets from week 1-4

- This was done twice a week, along with a climbing training session 6 days a week

So which exercises should you do and how often?

It really depends on your climbing ability!

- Beginners: If you’re a beginner, start slow and just go climbing! Start with low intensity and see how you feel the next day. Don’t overdo it, you want to make sure that you allow your body to build up the strength and endurance and avoid any overuse injuries. Take breaks in between attmepts if bouldering, and take rests when you feel a pump coming on if toproping. Listen to your body, only you know how you feel.

- Intermediate: ARC and 4×4 can be done in combination during the week (not on the same day) or you can alternate doing ARC one week and 4×4 another week. Build up to 2-3 times per week. If you’ve been climbing a while, hangboarding can be beneficial for increasing finger strength.

- Projecting also counts as endurance training if you have a lot of attempts. Give yourself some breaks!

- Advanced: All 3 of these are options for you! Again, work up to the intensity you need and make sure to give your body a rest in between hard training days.

About the Author

Andy Rivas is a 2nd year physical therapy student at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee NC, and he started climbing his first year of PT school. In his free time he enjoys reading, camping, spending time with friends outdoors, and visiting new countries.

Disclosure Statement

The information provided here is for educational purposes and is not medical advice. Please schedule an appointment with a licensed physical therapist or your primary care physician for more guidance and specific recommendations.

Research

- Draper N, Bird EL, Coleman I, Hodgson C. Effects of Active Recovery on Lactate Concentration, Heart Rate and RPE in Climbing. Journal of sports science & medicine. 2006;5(1):97-105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3818679/

- HEYMAN E, DE GEUS B, MERTENS I, MEEUSEN R. Effects of Four Recovery Methods on Repeated Maximal Rock Climbing Performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41(6):1303-1310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e318195107d

- Hörst E. Effectiveness of “Dangling Arm” and “G-Tox” Recovery Techniques. Training For Climbing – by Eric Hörst. Published June 2, 2015. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://trainingforclimbing.com/effectiveness-of-dangling-arm-and-g-tox-recovery-techniques/

- López-Rivera E, González-Badillo JJ. Comparison of the Effects of Three Hangboard Strength and Endurance Training Programs on Grip Endurance in Sport Climbers. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2019;66(1):183-195. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2018-0057

- Fryer S, Stoner L, Stone K, et al. Forearm muscle oxidative capacity index predicts sport rock-climbing performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2016;116(8):1479-1484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-016-3403-1

- Wan J, Qin Z, Wang P, Sun Y, Liu X. Muscle fatigue: general understanding and treatment. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2017;49(10):e384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.194

- Senderella. Improve your Climbing Endurance: A Guide to ARC Training. Good Spray Climbing. Published September 1, 2018. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://goodsprayclimbing.com/improve-your-climbing-endurance-a-guide-to-arc-training/

- House S. Bouldering 4×4 Drills. Uphill Athlete. Published June 13, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://uphillathlete.com/rock-climbing/bouldering-4-x-4-drills/

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.