Into the “Core” of Climbing

Have you hit a plateau in your climbing and are trying to figure out what to work on? Have you ever wondered if you need to include core training in order to reach that next level? Climbing is often considered a whole-body activity that works a lot of different muscle groups in the body, ranging from the upper extremities, or arms, to the lower extremities, or legs. As a result, training regimes developed for climbing can vary greatly, from regimes targeting upper extremity strength to regimes targeting lower extremity strength. Something that is almost universal amongst all climbing-related training regimes, however, is core training. So what makes the core so important for climbing?

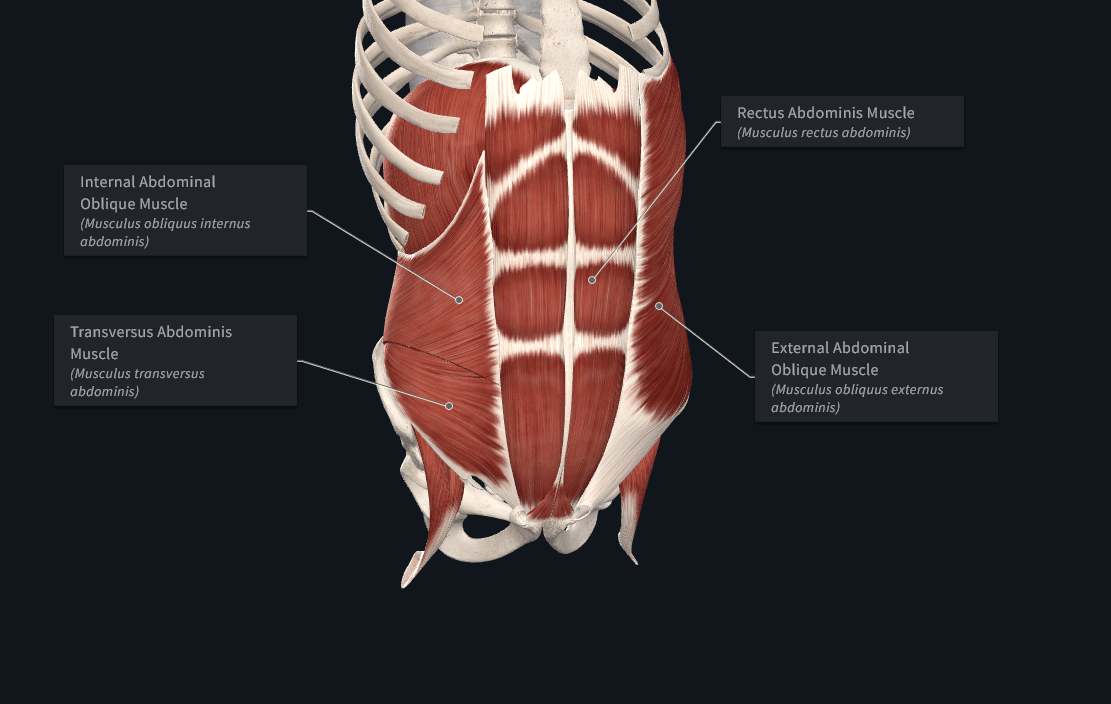

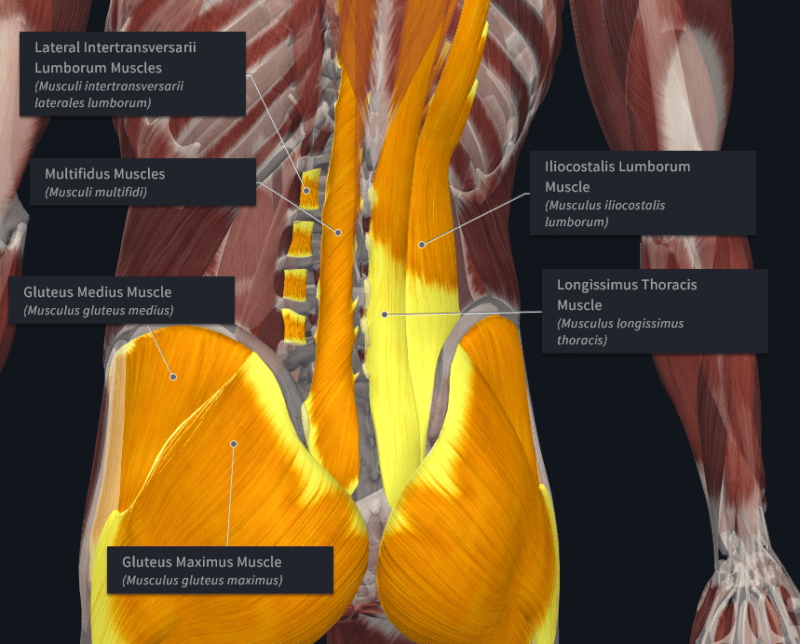

Before we address the function of the core in climbing, we must first look at what makes up the core. A common misconception about the core is that it is only comprised of the abs in the front; however, your core can be thought of as a band that wraps around your abdomen AND your back. In the front, your core is made up of the rectus abdominis (the popular “6-pack” muscle), external and internal obliques, and the transverse abdominis. In the back, your core is comprised of your superficial erector spinae muscles, deeper and smaller paraspinal muscles, and posterior hip muscles such as the glutes. Your core also has a roof and a floor. The ceiling or top of your core is comprised of the diaphragm while the roof or bottom of your core is made up of your pelvic floor muscles. All these muscles not only function to help you move into your next position when climbing but also help transfer force from your legs and arms to help maintain tension on the wall through their fascial connections. Fascia typically surrounds individual muscles, but it can also act to connect different muscle groups together. These connections are often referred to as kinetic chains.

Anterior Core Muscles

Figure 1. Complete Anatomy

Figure 1. Complete Anatomy

Posterior Core Muscles

Figure 2. Complete Anatomy

Figure 2. Complete Anatomy

Your core serves not only as a mobilizer of the body, but also as a stabilizer during movement. Because your core helps transfer force from your lower body to your upper body, or vice versa, it serves as a crucial bridge for the two regions. Your core is almost always active during climbing to help you move efficiently and the demand on your core only increases as the incline of the wall increases.

Insufficient core strength may present itself in many ways. You may notice trends in the movements you find most difficult. It could include your feet popping off when reaching up for the next hold or constantly cutting feet as the angle of the wall increases. It may also present as difficulty getting your feet back up on the wall or massive barndoors as you grasp the next hold. These events may indicate that you lack dynamic postural control, or the ability to maintain your center of mass within your base of support during movement. Situations described previously may not be solely caused by deficits in your core strength, but addressing core strength in your training can help reduce the possibility of your core being a limitation in your climbing.

Assessment

Because your core can provide two functions, mobility and stability, it is important to test both the strength and endurance of your core musculature.

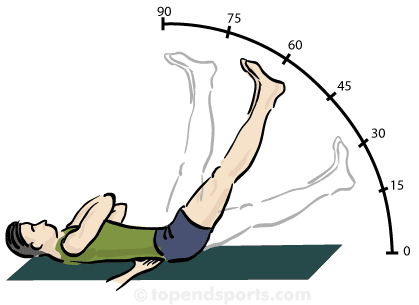

Abdominal Muscle Strength and Endurance Test

- Starting with your back in a neutral position (not pressed flat against the ground or excessively arched), you are going to bring your legs straight up towards the ceiling.

- Keeping your legs straight, slowly lower your legs down towards the ground without further arching your back off the ground.

- The test ends when your back begins to arch further from your starting position or you can no longer control the descent of your legs.

- Normative values:

- 90 degrees – Starting Position

- 90-60: Fair

- 60-15: Good

- 15-0: Normal

- Normative values:

- To test endurance, you will lower your legs to the point before your back arches and hold for as long as possible.

Testing Position

Example Video of Test

Avoid arching of the back

Back Extensor Muscle Strength and Endurance Test

- Starting on your stomach and with your hands behind your head, lift your chest and torso off the ground as far as you can. You may need someone to stabilize your legs.

- To test endurance, you will hold the highest position you can for as long as you can.

- Normative values:

- Fair: Can lift chest off ground.

- Good: Can lift chest and torso off ground.

- Normal: Can lift chest and torso off ground and maintain position easily.

- Normative values:

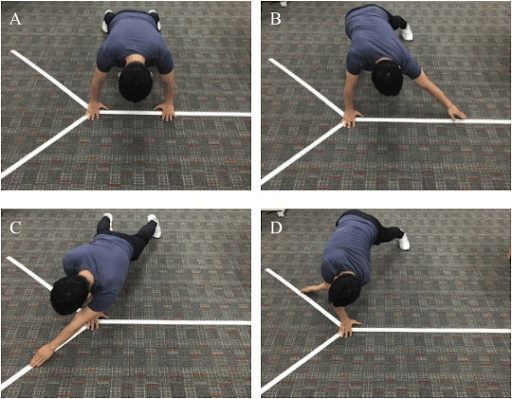

Back Rotators Muscle Strength and Endurance Test

- Start on all fours with your hips level with the ground. The test ends when your pelvis rotates during movement.

- Start by lifting an arm forward and then return to the starting position. Repeat for the other arm.

- Proceed by bringing one leg back and then return to the starting position. Repeat for the other leg.

- Continue by lifting one arm and the opposite side leg. Return to the starting position and repeat for the other side.

- If your hips drop at any point during the exam, the test ends.

- Norms:

- Neutral pelvis with arm: Good

- Neutral pelvis with leg: Fair

- Neutral pelvis with arm and opposite leg: Normal

- Norms:

Arm Only

Leg Only

Arm and Leg Combined

The aforementioned tests components of the core, but it is also important to assess the functional strength of your core. The Upper Quarter Y-Balance Test tests core stability during upper extremity movement while the Star Excursion Balance Test assesses core stability during lower extremity movement.

Y-Shaped Set-up:

Upper Extremity

Lower Extremity

Upper Quarter Y-Balance Test

The Upper Quarter Y-Balance Test (YBT-UQ) is a functional assessment that looks at the ability of a person to reach in 3 different directions with a single arm while challenging their stability. The test looks at how far a participant can reach outside of a narrow base of support without losing balance and can be easily performed at home. This test should be performed with both arms as a means of comparison. Using this functional screen, you can narrow down any differences between sides or if there are any weaknesses towards certain directions.

Materials:

- Y-shaped set-up

- Tape measure or ruler

- Piece of paper or flat cone or small object

Instructions:

- Start in a push-up or high plank position with the paper or cone under the arm you want to test. The arm that will remain stationary is going to be placed at the junction of the Y.

- Slide the paper out as far as you can without losing balance and return your arm to the original position leaving the paper behind.

- Measure the distance from the center of the “Y” to the ending position of the object.

- Repeat the test in a diagonal up and towards the stationary arm as well as in a diagonal down and towards the stationary arm.

Lateral

Diagonal 1 (Anteromedial)

Diagonal 2 (Posteromedial)

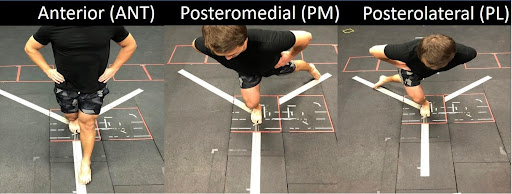

Modified Star Excursion Balance Test:

The modified Star Excursion Balance Test (mSEBT) is a functional assessment that looks at one’s ability to balance on one leg while reaching in 3 directions with the other. This assessment not only tests core stability during movement but can also inform you of how you compensate when your balance is being challenged. You can utilize an object to measure how far you can reach in each direction or record yourself performing the functional assessment to see which directions you may struggle the most with.

Materials:

- Y shaped Set-Up

- Tape measurer or ruler

- Piece of paper or cone or small object

Instructions:

- Start while balancing on one leg. The leg you are balancing on is the leg that is being tested.

- Slide the object in front of you as far as you can go without losing balance and return to your original position.

- Measure the distance between the center of the “Y” and the ending position.

- Repeat in a backwards diagonal as well as a forwards diagonal.

- Repeat with the other limb to compare sides.

Forward (Anterior) Direction

Posterolateral Direction

Posteromedial Direction

The assessments provided above will give you a general overview of your strengths as well as your weaknesses. It may be helpful to record yourself performing these assessments in order to better see how you are moving and how your movement changes over time. Depending on where you found your deficit(s) to be, the following exercises can be utilized to help strengthen your core for improved performance on the wall.

Mobility

The following mobility exercises target a few of the muscle groups that can affect core stability throughout movement as major muscles such as the latissimus dorsi (lats) or glutes can affect the position of your spine and hips if they are shortened or tight. “Tight” or shortened muscles can be temporarily addressed through stretching, but in order for changes in muscle length to be long lasting, you want to also strengthen these muscles in their new range of motion.

Latissimus Dorsi Stretch

Version 1

Version 2

Hip Flexor Stretch (3x30s)

Glute Stretch (3x30s)

Hamstring Stretch (2x45s)

Strength

1). High Plank + Variations

The high plank can be progressed to an elbow plank with the same variations in order to increase difficulty.

Arm Extension

Leg Extension

Arm and Leg Combined

2). Bridges

Double Leg Bridge

Single Leg Bridge

3).Shoulder taps

You can adjust the difficulty of this exercise by widening your legs to make it easier or bringing your feet closer to make the exercise harder.

Climbing Drills

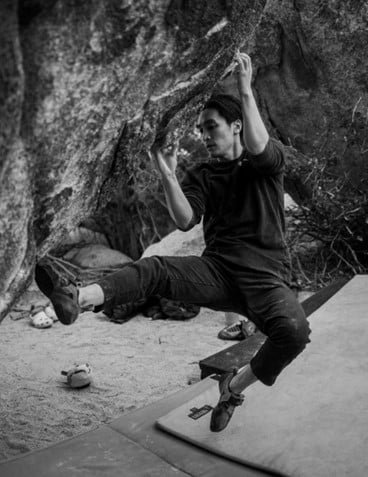

Climbing drills are a great way to integrate your mobility and strength training into the functional activity that you want to get better at. Climbing not only tests your core stability but also your upper extremity and lower extremity strength. Below are a few climbing drills that incorporate core stability with upper extremity or lower extremity movement.

- Toe taps on the wall

- With your arms fully extended and one leg on, emulate a foot slip and placing your foot back onto a hold.

- Can increase difficulty by working with smaller footholds or decrease difficulty by using larger holds.

- Active toe engagement with reaching.

- Working on maintaining tension through your foot as you are climbing, reach towards a hold above your head.

- Difficulty increases the further away you reach from the foot as well as by decreasing the size of the foothold you are on.

- Increasing the incline of the wall will increase core demand.

- Working on maintaining tension through your foot as you are climbing, reach towards a hold above your head.

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

If you are unsure about what aspects of your climbing should be addressed, seeing a physical therapist familiar with climbing and having a full evaluation done may help you develop a targeting training regime to improve your climbing. A physical therapist may provide you with the resources needed to not only improve your climbing but also help prevent injury later down the road.

The Research

- Saeterbakken AH, Loken E, Scott S, Hermans E, Vereide VA, et al. (2018) Effects of ten weeks dynamic or isometric core training on climbing performance among highly trained climbers. PLOS ONE 13(10): e0203766. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203766

- Huxel Bliven KC, Anderson BE. Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports Health. 2013;5(6):514-522. doi:10.1177/1941738113481200

- Granacher U, Schellbach J, Klein K, Prieske O, Baeyens JP, Muehlbauer T. Effects of core strength training using stable versus unstable surfaces on physical fitness in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2014;6(1):40. Published 2014 Dec 15. doi:10.1186/2052-1847-6-40

- Hsu SL, Oda H, Shirahata S, Watanabe M, Sasaki M. Effects of core strength training on core stability. J Phys Ther Sci. 2018;30(8):1014-1018. doi:10.1589/jpts.30.1014

- Park BJ, Kim JH, Kim JH, Choi BH. Comparative analysis of trunk muscle activities in climbing of during upright climbing at different inclination angles. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Oct;27(10):3137-9. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.3137. Epub 2015 Oct 30. PMID: 26644661; PMCID: PMC4668152.

- Gorman, Paul P.; Butler, Robert J.; Plisky, Phillip J.; Kiesel, Kyle B. Upper Quarter Y Balance Test, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: November 2012 – Volume 26 – Issue 11 – p 3043-3048 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182472fdb

- Afonso J, Ramirez-Campillo R, Moscão J, et al. Strength Training versus Stretching for Improving Range of Motion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(4):427. Published 2021 Apr 7. doi:10.3390/healthcare9040427

About the Author

My name is Kevin and I am a second-year Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) student at Chapman University. I have been climbing for about 7 years and I primarily boulder. I fell in love with climbing because it challenged my problem-solving skills and required such peculiar movements in order to solve. This later helped me foster my interest in physical therapy as I find movement analysis to be quite fascinating.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.