Balanced Climbing Shoulders

Balanced muscles around the shoulder are essential for climbing efficiency as well as to avoid uneven tension around the joint. Imbalance in muscles around joints leads to increased strain and stress in the soft tissues and can ultimately lead to tissue failure. The anterior (front) shoulder muscles and the anterior (front) chest muscles power pull ups and many climbing moves requiring reaching and pulling. The anterior muscles are predominantly the pectoralis, anterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi, and biceps muscles. These muscles can become dominant and overpower their oppositional muscle groups (those at the back of the shoulder and shoulder blade). Muscle imbalance around the shoulder can be avoided by training the posterior muscles of the back of the shoulder and shoulder blade.

Shoulder instability is a condition that can develop gradually from long-term, repeated exposure to straight-arm hangs, Gaston moves, and severe lock-offs, as well as from overzealous stretching or climbing on overhanging routes day after day without training of the oppositional muscles. You may notice episodic periods of ‘pain’ and/or ‘movement’ and/or ‘clicking or crunching’ in the shoulder when this imbalance sets in. Optimal shoulder balance is dependent on balance between the external loads of climbing and internal muscle forces. These internal forces are provided by the rotator cuff muscles. Most commonly it is the posterior rotator cuff muscles that are not in balance with the anterior cuff muscles that can lead to this condition.

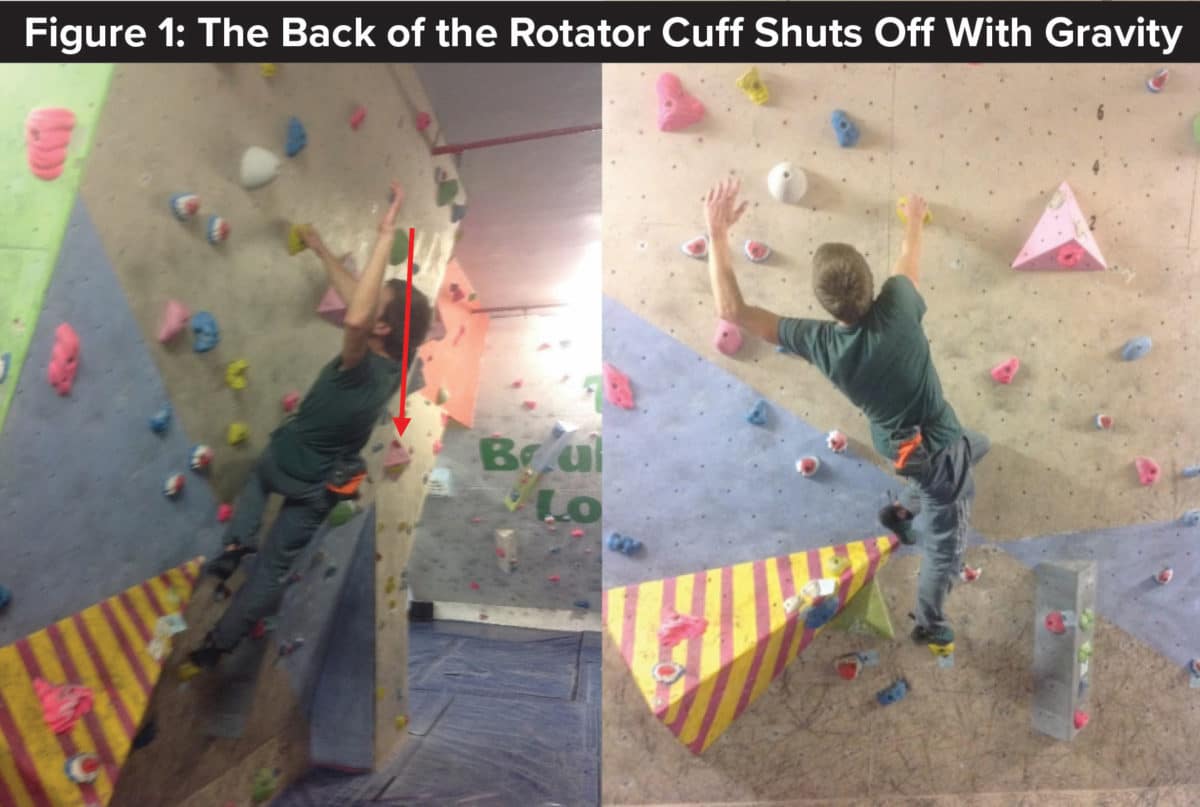

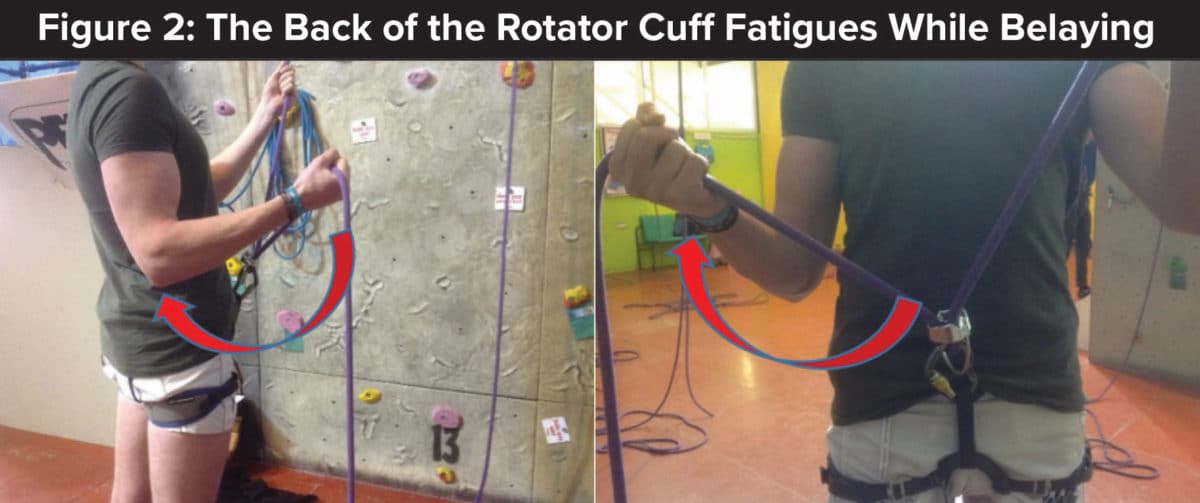

Below are two examples of muscle imbalance around the shoulder joint where the anterior muscles dominate.

- Example 1: The back of the posterior shoulder shutting off because of gravity leading to a dominance of the anterior muscles.

- Example 2: The back of shoulder overworking and fatiguing leading to a dominance of the anterior muscles.

Example 1. An example of when the posterior rotator cuff muscles can take a free ride and capitalize on gravity (figure 1: red arrow) while climbing is while reaching particularly on an overhang. As the arm reaches back, gravity assists the reach instead of the posterior rotator cuff muscles working. This leaves the anterior muscles doing all the work when extending the arm to reach for a hold.

Example 2. Although the posterior cuff muscles are required to work when taking out gear and reaching, while belaying repetitive external rotation of the shoulder fatigues the posterior cuff (figure 2).

I find that many climbers complain to me that they are ‘tight’ in their anterior chest and shoulder muscles and tell me that they are stretching out these muscles. However, when I examine them they are hypermobile (have excessive motion) in the shoulder joints and while stretching these muscles they are also stretching the front of the shoulder joint too. The front of the shoulder and chest will feel ‘tight’ if they are not in balance with the posterior shoulder muscles. This is because muscles can only relax when muscle balance on both sides of the joint is established. So, the ‘tightness’ is a misleading perception and sensation. What is required is a counter balance in the muscles at the back of the shoulder i.e. in the posterior roator cuff cuff; not stretching.

Figure 3: How do you know if you have an imbalance in the posterior cuff muscles? In Figure 3a&b. a discrepancy is noted between the range of external shoulder rotation between when the upper arm is supported and unsupported. Ideally the arm should be able to achieve full range in the unsupported position equivalent to that in the supported position as in Figure 3c. In Figure 3a the posterior shoulder muscles are made to work against gravity and it is evident that they are not working into the full available joint range. This shows the difference between supported and unsupported range of movement and active control of the shoulder joint.

The following exercises can be used to bias and stimulate the posterior cuff muscles:

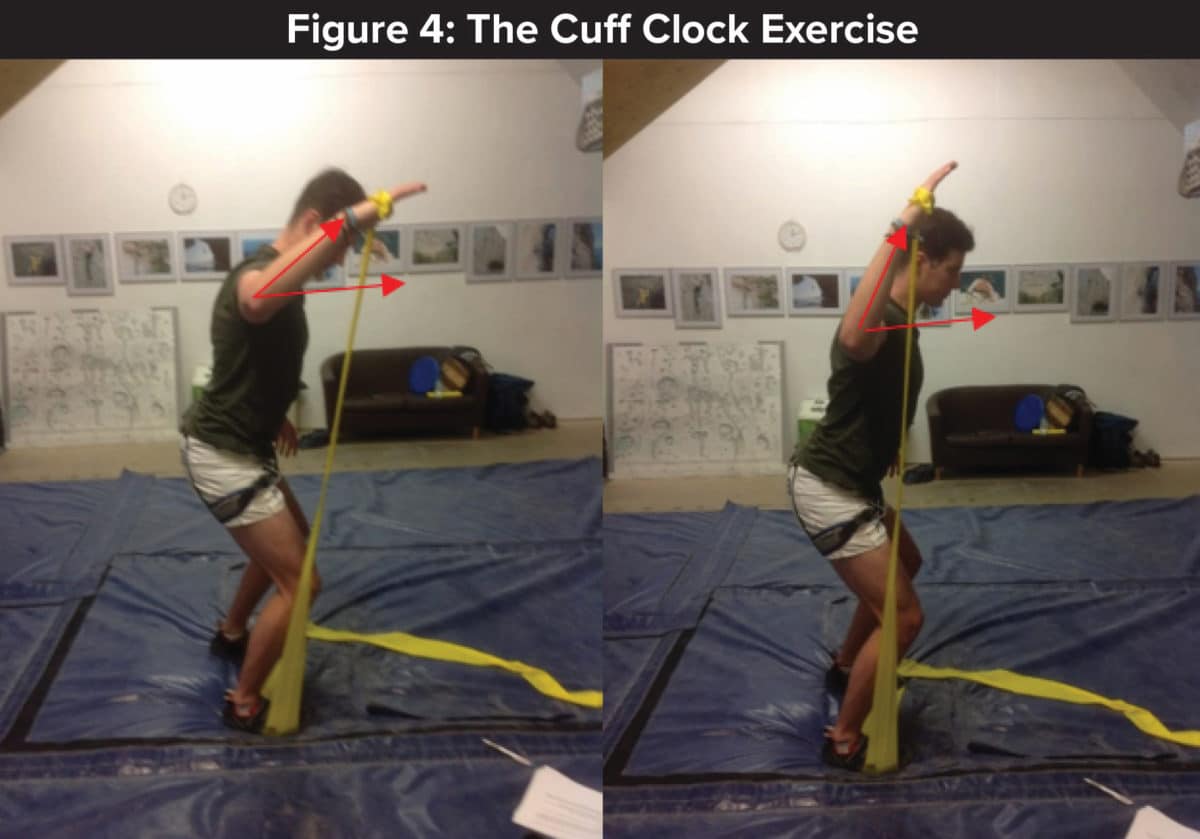

Figure 4. The cuff clock works the agonist shoulder external rotators. Mirror the climbing position. Attach the band to the same side foot and imagine that the elbow is the fulcrum of a clock and the forearm the second hand. Slowly and deliberately move the forearm into external rotation making every second count. You may need to support the upper arm initially if this is too difficult. It is essential that you make sure you can do the movement in a controlled manner and that you do it through all your available passive external rotation range. This can also be done with a free weight.

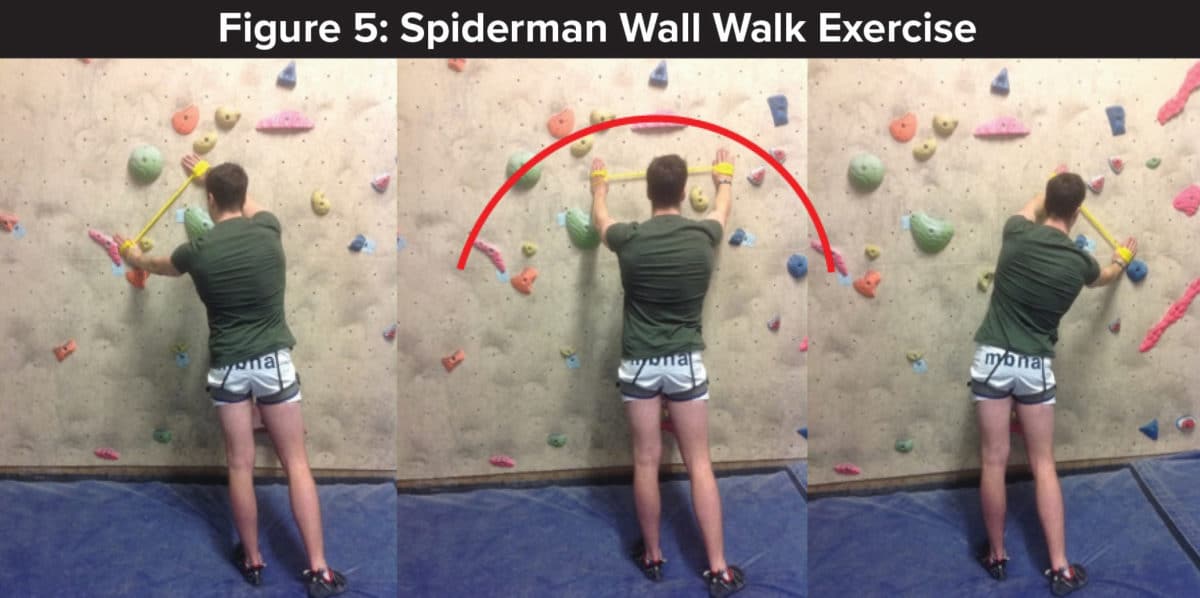

Figure 5. Spiderman wall walks. Stand 1m away from the wall. Attach the band between the hands and lean forward onto the wall. Walk the hands around the wall in a semi-circle maintaining tension in the band.

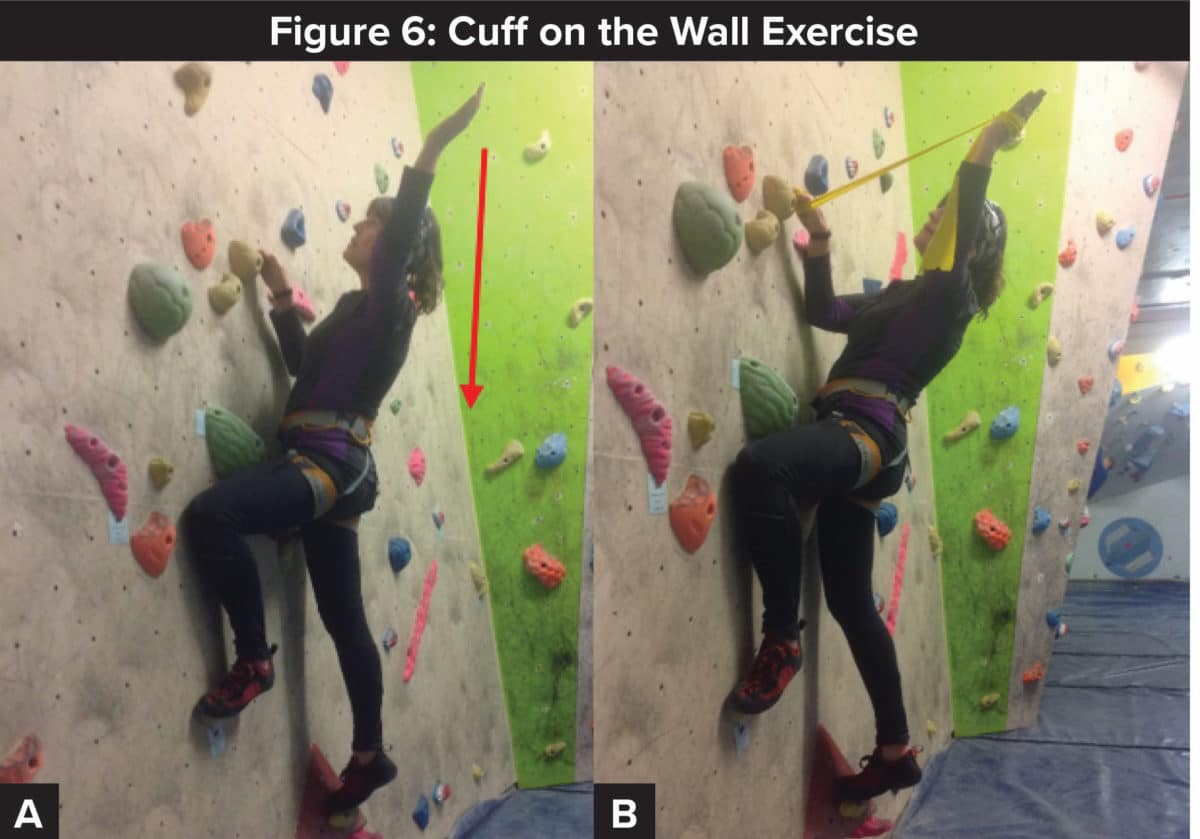

Figure 6. Cuff on the wall. In figure a. gravity (red line) is doing the work for the posterior cuff. In the exercise in figure b the attached band between the hands ensures that the posterior cuff is activated while mimicking a reach.

Author: Tanya Anne Mackenzie PhD

HAPPY CLIMBING!!

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

[…] Full Article: Balanced Climbing Shoulders […]

Every bit of this is relavent to me. I’ve had this ongoing problem for about six months and it’s getting worse by the day. Of course I haven’t stopped climbing, only started doing more shoulder workouts that I didn’t usually do, as well as chest workouts.

My question.

Is the damage done reversable?

I’ve had serious crunching in my right shoulder and pain, discomfort and lack of mobility, I would love to be back to normal again…

As described in the article, shoulder pain can often occur from imbalances in the shoulder that develop over time. The exercises in the article can improve the balance of the muscles surrounding the shoulder and restore optimal shoulder function. However, if the exercises are painful, it is recommended to either scale them down so they are pain-free or see a physiotherapist to identify why you have the pain.