Trying Hard After Finger Injuries

Some time ago, you were out climbing. You tried this limit move a few times in a row, and on the last go, you heard the infamous POP.

Fast forward a little bit, maybe you consulted a professional, maybe you did some exercises your friend recommended to you, and your finger is feeling good. Now the big question in your head is, “can I try hard again?”

Any climber who deals with a finger injury is going to have a period of time where they wonder if and when it’s okay to start pulling hard. The purpose of this article is to help you navigate the different factors to take into consideration when you’re at this crossroad. The main two factors you’ll need to be aware of when making this decision are return to sport criteria and tissue healing time.

Criteria for Return to Sport

Since this article is primarily about the end stage of the rehabilitation process and return to sport, I won’t go into detail about how to diagnose different finger injuries or the beginning of the rehabilitation process. However, if you want to know more about that, Dr. Jared Vagy (AKA The Climbing Doctor) was a guest on the Training Beta Podcast and delves into that information; you can find it here

A lot of times, you can begin easy climbing again in the intermediate, or sometimes even early, stages of the rehab process. Here though, we’re going to discuss some criteria to meet that’ll give you a green light to crank on that hand again. While the timeline will be different based on specific hand injury and severity of that injury, there are a few key things that can help you determine if you’re all good to really pull.

Firstly, let pain be your guide. While it’s not necessarily an end all be all as we’ll discuss later, it is an important factor. If you start trying hard on a project and experience pain that’s greater than normal or continues to get worse beyond some anticipated discomfort as you climb, it’s probably best to back off some. Second, ensure you have full active range of motion in your fingers, hand, and wrist. Chances are, by this point in the rehab process, you’ll have already regained full ROM, but we have to cover all our bases. Now that we’ve covered pain and mobility, let’s talk about strength. While your initial thought might be to avoid climbing, hangboarding, or otherwise stressing the tissue, these are actually a necessary part of the process. If a tissue isn’t loaded enough, it won’t be stimulated to remodel. That being said, if you haven’t hopped on a hangboard at all, it might be a good idea; hangboards are often used in the later stages of rehab. Dr. Esther Smith has created an awesome protocol for finger rehabilitation that includes a hangboard which can be found here. Next – and this goes for everybody – warm up! A 2009 study by Andreas Schweizer showed that it takes about 100-120 climbing moves of progressing difficulty in order to fully warm up the flexor tendon pulleys (Schweizer, 2009). Even if you don’t have a pulley injury (or any injury for that matter), warm up to keep it that way. In my opinion, the best warm up is the same or very similar to what you’ll be doing for your workout, just at a lower intensity. While this can be easy in a climbing gym where you have countless problems or routes at your disposal, it is less viable if you’re pulling straight up to the project. In these cases, I like to do some jumping jacks, squats, lunges, and hip hinges to get the blood flowing (unless the approach adequately did that already) and some band exercises for the shoulders. Finally, I use a flashboard to warm up my fingers, doing some gradually increasing sub max isometric pulls and some finger curls. This is just what I’ve found works for me, you do what works for you! A caveat though, if you’re just going to climb some easy routes as your warmup, try and do similar movements to what you’ll have to do on your project. If you warm up on jugs and crimps, but your project has a crux sequence with a couple two finger pockets, your hands won’t be as prepped and ready as if you had done some easy pocket climbing as part of your warm up.

An article in JOSPT about criterion-based rehabilitation progression and return to sport in ACL Reconstructions listed a 90% or greater quadriceps index was required in order to begin a return to sport progression (Adams et al., 2012). This simply means that the involved quad has to be at least 90% as strong as the uninvolved quad in a Maximal Voluntary Isometric Contraction (MVIC) test. To my knowledge, no crossover research has been done so far, but it would be feasible (and fairly simple) to obtain a finger strength index with just a hangboard and a scale. If you were to stand on a scale underneath a hangboard and pull on an edge in a half crimp as hard as you can with your uninvolved hand followed by your involved hand, the weight drop on the scale will tell you how many pounds of force you exerted on the hangboard. Let’s say you weigh 170 pounds, and with your uninvolved hand you pull hard and the weight on the scale drops to 60: you pulled 110 pounds of force. Then you check your involved hand and pull: the weight drops to 90, so you pulled 80 pounds of force with that one. This means that your involved hand is only about 73% as strong as your uninvolved hand, and it might be a good idea to do some more strength training before you really start limiting on boulders or routes.

Now let’s say you’re all good with everything: pain free, full ROM, you warmed up, your fingers are strong, and you’re ready to try hard. It’s easy to feel good and then accidentally go overboard with your volume.

My best friend dislocated his shoulder while climbing a few months ago. He did almost everything right: took a bit of rest time, saw a PT, did his rehab exercises at home, and slowly reintroduced climbing into his routine. Everything was perfect, and then one night he felt really strong and got super psyched pulling on his homewall with friends. After his warm up he started doing some spanned out, shoulder intensive moves, and 20 minutes later…clunk clunk. He felt his shoulder tweak again. It wasn’t as bad for him this time, but this is an important lesson in load and volume management. Let’s say you’re coming off a lumbrical injury. As you begin trying hard again, you put your hand in a two finger pocket for the first time since your injury and pull…nothing happens. No pain, no weakness, it feels good. That doesn’t mean that you can climb on two finger pockets for the next 30 minutes, or even 15 minutes, straight. The tissue may be ready for that level of stress again, but it won’t necessarily be ready for the volume yet. Spend some sessions slowly building up that training volume so as to minimize the risk of re-injury.

Tissue Healing Time

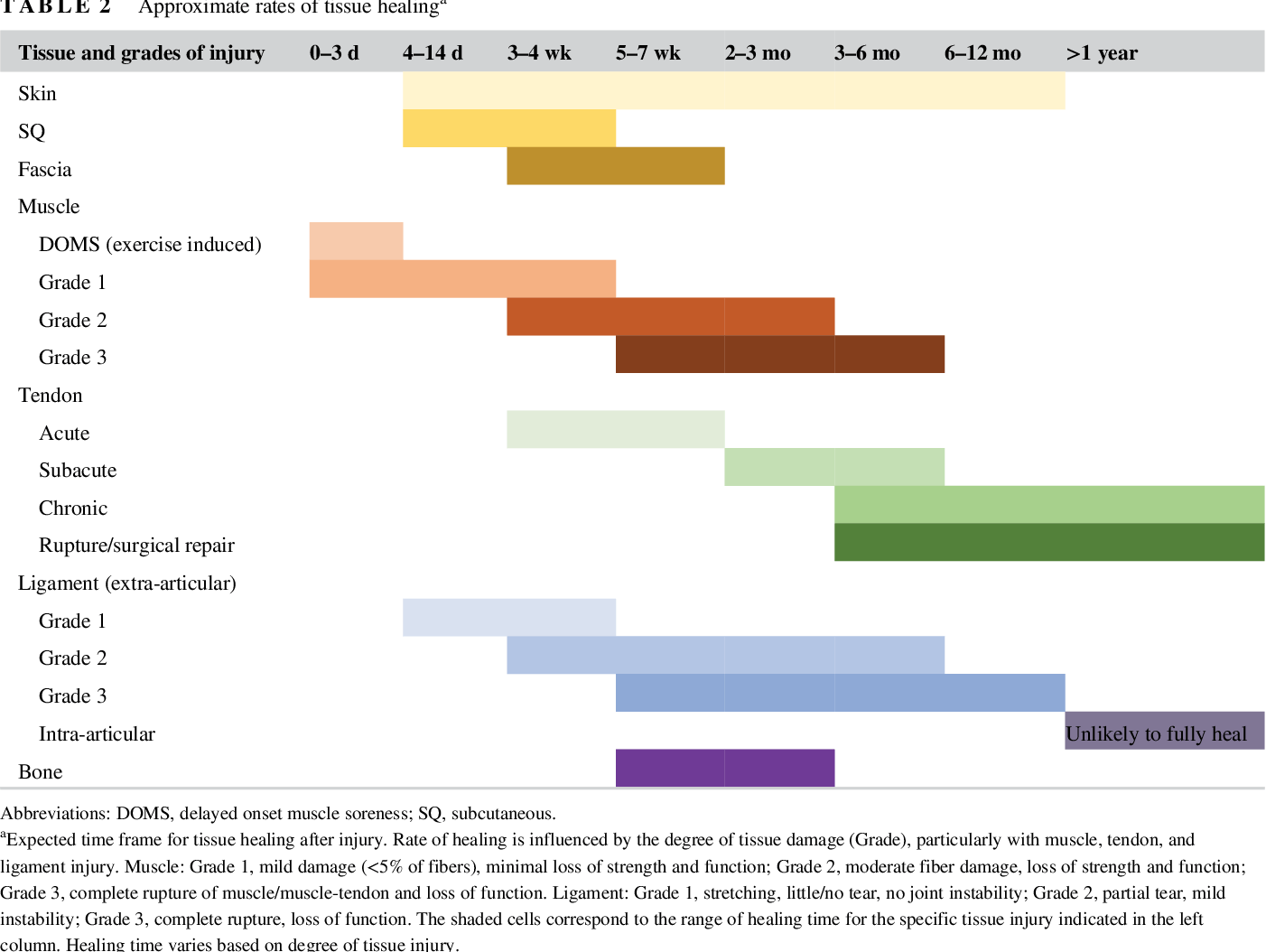

Warren Buffett once said, “No matter how great the talent or effort, some things just take time.” It’s important to not only use a criterion based protocol but also a time based protocol. In order for tissue to be able to handle load again, it must have had enough time to rebuild and remodel. The time required will depend on the injury and severity. The general rule of thumb for soft tissue healing is that muscles heal faster than tendons and tendons heal faster than ligaments due to the varying vascularity of the structure and also varying biological structure. Below is a table by the Prehab Guys with approximate tissue healing rates depending on type and severity of injury.

In the later stages of rehab, you most likely already know what injury you have and how severe it is. This chart is meant to serve as a guide for letting you know how long the healing process will take. Even if you do everything right, you still need to give that tissue enough time to recover. That said, everything has a “range” of how long it can take to heal. While some aspects are beyond our control, there are certain things you can do to keep yourself on the lower end of the spectrum. Consuming enough protein for tissue repair and remodeling, staying adequately hydrated, getting enough sleep, and even maintaining a positive mindset are all vital to improving recovery, both in training and injuries.

Another note, there is a time based protocol for finger taping in respect to pulley injuries.

Schoffl et al found that the H taping method was the most beneficial taping method for a pulley sprain. In a Grade I or II sprain, the taping period is about 3 months. In a Grade III pulley sprain, the taping period is about 6 months. Finally, in a Grade IV rupture, the taping period can last over a year (Schoffl, 2006). If you’re looking for a “how to” for the H-taping method, click here. While the H taping method has been shown to be beneficial for the re-introduction to climbing after a pulley injury, it has not been shown to help in the prevention of pulley injuries. So, if you’re not currently injured, don’t worry about taping up to reinforce the pulleys; chances are, it’s not going to do anything.

Psychological Barriers to Climbing Hard After Injury

The mental state is such an important part of climbing, and it’s worth noting that sometimes we can hold ourselves back from trying at our limit due to the fear of reinjury. Maybe the tissue doesn’t feel as strong as it used to, so you think that if you pull hard on that 8mm crimp it’s just going to pop again. Or, maybe you’re experiencing some pain or achiness that just doesn’t want to go away. While these two things are important (and you should take them into consideration), sometimes our brain can work against us. If you’ve waited the allotted time for the tissue to heal and been consistent with your progressive rehabilitation program but you’re still having some chronic pain, there’s a chance that it could be a projection from your brain. As we know, the brain is extremely powerful, and it can sometimes even make us feel things that aren’t there. If you are accustomed to having your finger hurt when you do certain things, sometimes the brain can manifest that feeling even when there’s no longer any damage to the tissue. If you’re reaching up for that next crimp on your route and think that it’s going to hurt to pull on it, it probably will. Note that this isn’t always the case, but it is something to be aware of, especially if you’ve done your due diligence to rehab it and are still having some lingering pain. I have another friend who had a pulley injury a few months ago. He was keeping me updated with how it was doing, but one day he told me that he had “hit a wall” in his rehab. He had been doing his hanboarding sets at a certain percentage of his bodyweight for two weeks but he was not experiencing any improvements in pain relief. I said that if I was him, try to increase the percentage anyway, push into the discomfort a little bit, and see what happens. He reported back in a couple weeks that it made a world of difference and his finger felt much better. Now, this isn’t specific medical advice, but for him it worked out, most likely due to the fact that his discomfort was keeping him from progressing his rehab even though there was no additional tissue damage occurring at the site of the discomfort. Therefore, pushing past that barrier helped his brain realize that the pain signal wasn’t necessary.

Dr. Adriaan Louw, the founder of Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE), has researched outcomes of educating patients about their pain. A systematic review of 13 Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) showed support of using PNE for musculoskeletal pain for the parameters of reducing pain, improving patient knowledge of pain, improving function/lowering disability, reducing psychosocial factors, enhancing movement, and minimizing healthcare utilization (Louw, 2016). All that to say, patients in those 13 studies showed improvements in all those facets from simply being educated about pain. The brain is powerful!

Final Comments

Finger injuries can be scary, and it can be difficult to determine when it’s okay to begin really pulling. Here are the main pearls:

- “When” is subjective: it’s completely dependent on the individual and his/her respective injury

- Full ROM and reduced pain are musts.

- Load. The. Tissue.

- Manage your volume.

- Be patient. Healing takes time.

- Don’t let your brain play tricks on you. Sometimes mild discomfort is okay (take it with a grain of salt).

- More research is needed to develop a true criterion based protocol.

- Consult a medical professional for your individual needs.

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

Note, this article is not intended to treat, cure, or prevent any medical disease, condition, or injury. Consult a Doctor of Physical Therapy or orthopedic specialist for specific information relating to your diagnosis/pathology.

About the Author

My name is Brandon Whitmore, and I am currently finishing up my second year of DPT school at Texas Woman’s University – Dallas campus. I have been climbing off and on since 2016, but it’s only been a couple years since I really dove into training and getting better. I spend my free time training in the gym on the sets and the training boards, and I try to get as much outdoor climbing in as I can. Connect with me on Instagram @chronicles_of_b.whitty or feel free to shoot me an email at bwhit968@gmail.com.

References

- Adams, D., Logerstedt, D. S., Hunter-Giordano, A., Axe, M. J., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2012). Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 42(7), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2012.3871

- Elnaggar, S. (2022). What You Need to Know About Tissue Healing. The Prehab Guys. Retrieved from https://theprehabguys.com/tissue-healing-timelines/

- Louw, A., Zimney, K., Puentedura, E. J., & Diener, I. (2016). The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapytheory and practice, 32(5), 332–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2016.1194646

- Schweizer, Andreas. (2009). Biomechanics of the interaction of finger flexor tendons and pulleys in rock climbing. Sports Technology. 1. 249 – 256. 10.1002/jst.68.

- Schoffl, I., Einwag, F., Strecker, W., Hennig, F., & Schoffl, V. (2007). Impact of taping after finger flexor tendon pulley ruptures in rock climbers. Journal of applied biomechanics, 23(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1123/jab.23.1.52

- Smith, E. (2017). Hang Right: Healing Finger Injuries. Retrieved from: https://www.blackdiamondequipment.com/en_US/stories/experience-story-esther-smith-nagging-finger-injuries/

- Vagy, J. (2022). How to Heal Finger Injuries in Climbers. The Training Beta Podcast. Retrieved from https://theclimbingdoctor.com/portfolio-items/12850/

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.