Climb On after a Concussion

By Stacey Castaldo, SPT, CSCS

It was just another day at the climbing gym, I’d done a couple warm-up routes, and now I was just starting up a new 5.12 in a shallow corner. I high-clipped the second bolt, and began reading my next move; it wasn’t immediately intuitive. The next hand was quite a reach up and to the left. It took me a few moments, but it became obvious, left foot stemmed up high, turn my right side into the wall by pushing off a big hold far out to the right, then power off the left foot to reach the high left hand. I had that quick rush of satisfaction and excitement as I moved through it; it flowed well, I felt strong as I drove upward, and then—bang—I felt a sharp pain on the top of my head and I hung there stunned.

Had I just hit my head on a bolt? How does that even happen? If you had told me I’d hit my head on the wall, I would have guessed it would be on a big sloper or volume. “Are you ok? Do you wanna come down?!” yelled my climbing partner. “No, I’ll be fine, just give me a minute”. It wasn’t that bad. I’ve banged my head tons of times, shook it off and went right back to what I was doing. I hadn’t blacked out, I wasn’t dizzy, it was fine. “I really think you should come down” she said again. I protested once more before pulling my hand away from my head; it was covered in blood. “Ok yeah maybe you’re right”. I had a small head laceration, so we drove to urgent care for some staples. I still didn’t feel dizzy or nauseous, I was alert, my vision was fine, my eyes were tracking normally; I had no immediate signs of a concussion. I went home and thought that was that; I had no idea the rollercoaster that was waiting for me over the next 3 months.

At the 24 hour mark is when I started noticing things were off. My entire physical therapy cohort was standing in the hallway waiting for our professor to arrive. Everyone was talking at once, which normally would have had no effect on me whatsoever. I’m the type of person that gets out of my quiet house to go study at a busy coffee shop because I find the background noise calming. Not this time, this time it was panic-inducing; it felt unbearable, I had to get out of that hallway. Luckily, my professor showed up and the noise dissipated, but that wasn’t the end. Over the next couple days I became aware of how off I truly was; I was tired, in a constant mental fog, my emotions were all over the place, and above a certain level, noise was intolerable. A week later, once I began trying to get back into my normal exercise routine, the delayed nausea & severe headaches began; I was undoubtedly concussed.

Concussions aren’t a climbing specific injury. Of course, you could hit your head on the wall like I did, but you could also hit it in a myriad of other situations: a car accident, standing up underneath an open cabinet, belaying at a chossy crag without a helmet, and so forth. Like any injury, it will have an impact on your return to climbing; but unlike many musculoskeletal injuries, this impact will look very different for everyone, and may be insidious enough that you can almost convince yourself that it’s in your head (and not literally). If you’re like me, and most climbers are, all you want to know is ‘when can I get back to climbing like normal?’. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to that question; which is why, especially if you are struggling to return to your previous level of exercise post-concussion, it is important to work with a healthcare provider, such as a physical therapist, that is experienced in treating athletes with concussions.

Symptoms & Post-Concussion Syndrome

While typical concussion symptoms include blacking out, dizziness, vertigo, nausea and vomiting, headaches, balance issues, and vision/noise intolerance, many symptoms are less obvious. Some of the common less obvious symptoms include: sleep disturbances, drowsiness, mental ‘fog’, difficulty concentrating, slow reaction times, digestive disturbances, and emotional symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or irritability. While the presence of only one of the above symptoms is enough for a concussion to be suspected, none of these are specific only to concussions, and the persistent presence of these symptoms does not necessarily mean that there is an ongoing physiological brain injury. This is important to understand, because although most concussion symptoms do resolve within 7-10 days, especially in younger athletes, it is not uncommon for some symptoms to last 1-3 months.

Persistent Post-Concussion Syndrome is defined as the presence of concussion related symptoms that began at the time of the injury and do not resolve within one month11. It is not entirely clear what causes some people to have prolonged concussion recovery times, although a few studies have identified several risk factors. These include: experiencing amnesia, feeling dizzy at the time of the injury, presence of vestibulo-ocular dysfunction (blurred vision, dizziness, and/or nausea with head motion), greater severity, older age, female sex, history of previous concussions or migraines, and inappropriate management of a current concussion.

So what should you do if you suffer a blow to the head and suspect a concussion (or you’re like me and don’t suspect one even though you should)? First, ideally you do not want to be alone for the first few hours directly following the incident, as the onset of concussion symptoms can be delayed. If you’re at the crag or gym, stop climbing, have someone help carry your gear and drive you home, or if necessary, to a hospital. It is important to get evaluated by a licensed healthcare provider. Proper identification and management of a concussion from the time of onset is critical for optimal care and reduction of persistent post-concussion symptoms. If you don’t need emergency treatment, your primary care provider, a sports medicine physician, or a physical therapist can provide a post-concussion screen. Again, concussions present differently for everyone, and diagnosing a concussion can be challenging, so your health care provider will perform a series of tests and ask questions about your symptoms, history, and life circumstances to determine the proper course of treatment. They will also be able to rule out any serious cervical spine injury and determine whether imaging is needed.

Depending on the circumstances, treatment may include physical therapy, especially if you are experiencing headaches, dizziness or imbalance. However, these are not the only symptoms that can make return to climbing difficult. Of those three, I only experienced headaches, and it still took me about 4 months to get one hundred percent back to pre-concussion levels of intensity. So even if you are not experiencing all of these, working with a physical therapist that has had additional training in concussion rehabilitation, and that understands the sport of climbing, can make returning fully to climbing quicker and less daunting.

What to Expect during a PT Evaluation

If you suffer a head injury during a climbing competition or other organized sport competition, there will likely be a healthcare professional present to perform a sideline screen. This is not a comprehensive evaluation and will be followed up by a more comprehensive examination away from the sporting event. As mentioned, this exam can be done by a primary care provider or sports medicine physician, but it can also be done directly by a physical therapist. Your physical therapist will be able to determine whether PT is necessary for recovery and returning to sports, and whether they need to refer you to a specialist for any concussion-related cognitive or mental health complications. There are four main areas that a physical therapist will evaluate. These are neck function, vestibulo-ocular function (described above), motor function such as balance and coordination, and exertional tolerance. Dysfunction in any of these areas can contribute to a variety of symptoms, so it’s important to determine which of them are causing your individual symptoms so that a proper recovery plan can be recommended.

To assess if any musculoskeletal problems in your cervical spine are contributing to your symptoms, a physical therapist will examine your neck, upper back and jaw muscles for any tenderness, check range of motion, muscular strength and endurance, and the mobility and alignment of your joints. Next, they will check for any dysfunction in your vestibular system. Even if you are not feeling dizzy or having vision problems, it is important for your therapist to test your vestibulo-ocular function because there still can be subtle impairments that are contributing to other symptoms.

To test your vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), which is your vestibular system’s ability to communicate with your eye muscles to adjust your vision when your head moves, your therapist will perform several tests that check how well and smoothly your eyes can track a target, how well your eyes can realign and focus when your head or a target is moved rapidly, and how well you can focus on a target far away when your head is moved back and forth continuously. Another vestibular test your PT may perform is called a Dix-Hallpike test for BPPV (Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo). If you are experiencing vertigo (the sensation that the room is spinning) with head movement, you may have knocked loose some of the small crystals in your inner ears that help sense head movement. While this sounds scary, it is actually very relatively quick and simple to fix.

Motor function testing involves balance, coordination, and dual/multi-tasking (performing a mental task while simultaneously performing a physical activity or other complex combinations of tasks). There are dozens of balance and coordination tests available that your physical therapist could perform, but some examples of the most commonly used for sports concussions are the Balance Error Scoring System, which tests your ability to maintain your balance in fixed positions on various surfaces; the Star Excursion or its cousin, Y-Balance Test, which tests balance in a more dynamic manner; and the Finger-to Nose, Heel to Shin, or Tandem (heel to toe) walk tests for coordination.

Lastly, because climbing is a strenuous sport and often climbers also engage in other strenuous activities, it can be very helpful for a PT to perform an exertional test to determine if any intolerance or autonomic imbalances are present. The autonomic part of your nervous system regulates the involuntary processes in your body, many of them directly related to exercise, such as heart rate, blood flow, sweating, and the release of adrenaline and other important hormones. Because the nerves that communicate between your brain and body have signaling centers in the neck and the base of your skull, it is common for the function of this signaling to get disrupted by a concussion. A symptom-guided, graded exertional tolerance test can help establish a baseline and help guide your therapist in designing an aerobic exercise training program for you in order to return your exertional tolerance to its typical levels and promote brain healing. One of the common graded exercise tests used is the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test.

Returning to Climbing

Besides seeing a clinician for an evaluation, current guidelines recommend an immediate period of physical and cognitive rest. Yes, this means take a break from climbing. During this time, utilize low intensity stress management techniques, such as yin-style yoga, meditation, deep breathing exercises, going for leisurely walks, limiting your screen time, and getting a good night’s sleep. That being said, research has shown that complete rest longer than 2-3 days may actually slow recovery, so after an initial period of 24-48 hours of relative rest, it is recommended that you begin a gradual return to activity. I cannot stress this enough, if you are diagnosed with a concussion, returning fully to sports without complete recovery—meaning the absence of post-concussion symptoms—could place you at a more significant risk for another concussion, and/or persistent post-concussive symptoms.

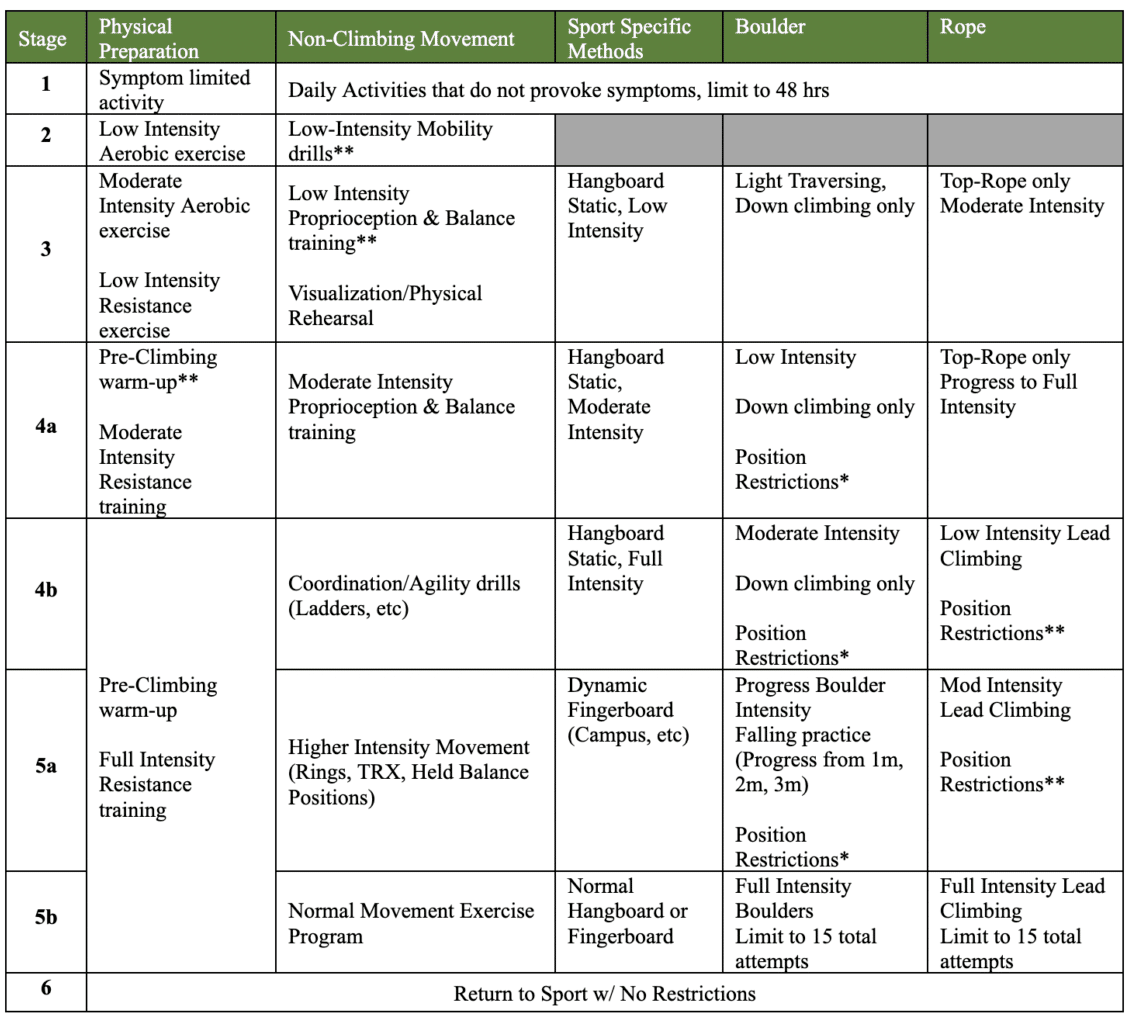

The current consensus on return to activity after a concussion is to follow a ‘step-wise’ strategy. The next ‘step’ should only be taken if the last step does not cause symptoms either during or for 24 hours after activity. If any new symptoms come on, go back to the previous step. The Climbing Escalade Canada Concussion Protocol1 has recommended the following return to sport strategy:

The first two stages involve returning to daily activities, work or school, followed by the introduction of light aerobic exercise and mobility drills. Once you can handle these without any symptoms, then it is time to return to a modified level of climbing. Start with sub-maximal gym climbing on top rope or light traversing with downclimbing. Lead and bouldering falls involve a large amount of fast head movement (not to mention the potential of actually hitting your head), and should be avoided at first. Low intensity strength training, hangboarding, and balance/proprioception exercises can also be added, and now would be a great time to work on that hip and shoulder mobility you’ve been putting off.

Visual & physical rehearsal can also be helpful in maintaining climbing fitness while you’re unable to climb hard. Research has shown8 that dynamic mental rehearsal techniques can improve performance by recruiting the same neural networks in the brain that are used to perform the movement, helping to reinforce muscle memory. Additionally, the brain networks that drive the psychological aspects of performance are also recruited and linked to the physical aspects, which has been shown to help athletes achieve personal bests…just ask Adam Ondra.

Until you are back to full intensity with any activity listed above, there are some important positions or actions you should avoid that may aggravate your symptoms or put you at risk for further injury or longer recovery. No holding your breathe or Valsalva maneuvers for the first 3 stages. A Valsalva maneuver is a breathing technique involving a forceful exhalation attempt, but your airways are closed so that no air escapes; it is also referred to as ‘bearing down’. Avoid inverted positions as well, meaning your heart is over your head. Sorry yogis, no down dogs or handstands for now. Exercises that involve a lot of rotational head movement can also be aggravating. Think band exercises and light dumbbells or kettlebells (but no swings!) to start with and progress gradually. When bouldering, avoid positions that increase the likelihood of falling on your side, back, or stomach, like having your feet and hands at the same height, feet overhead, foot first moves, and steep overhangs. Also avoid friction slab problems where there is a risk of hitting your head or body on a volume or large hold because of a slip. While top-roping, avoid routes with long overhangs that will cause you to swing far away from the wall if you come off. When you start lead climbing again, avoid positions that increase the risk of inverted falls and collision with the wall or your belayer, such as having feet overhead, large distances between draws or difficult clipping positions in the first 4 draws, hard moves on severe wall angle changes, horizontal edges, and slab terrain with volumes. Avoid these activities until stage 5b above, when you are back to full intensity (where the position restriction is no longer on the chart). As you increase lead climbing intensity, practice incrementally taking more falls each session as you can tolerate. For instance, lead climb until you take a fall, then switch back to top rope or climb routes that are manageable enough that you can avoid falling for the rest of the session. If this doesn’t provoke any symptoms over the next 24 hours, take two falls the next session, and so on.

Over the course of a few weeks to months, you can build yourself back up to pre-concussion levels. How long this takes will vary between individuals, it may take a couple weeks or 3-4 months. Be patient, listen to your body, and allow your nervous system time to heal. If you overdo it one day or one weekend, scale back and build back up more slowly. Again, if this seems daunting or if you are having trouble implementing this program, seek out a physical therapist experienced in treating concussions (and ideally climbers) to help you navigate the process. Sometimes just the simple accountability and support that a therapist provides can make all the difference. Stress management is important for concussion recovery, so if having a professional to check-in with and guide you can alleviate a significant amount of stress, that might be the missing link. Additionally, depending on your individual symptoms, other therapy exercises may be helpful in promoting recovery, and a physical therapist possesses the knowledge and skills to identify if balance training, vestibular rehabilitation, neck strengthening and/or mobilization, or other forms of therapy are needed.

Off-the-Wall Recovery

Neck pain and neck-related headaches are very common post-concussion complaints. Physical therapy in the form of neck and upper back strengthening, manual therapy, and stretching have shown to be helpful when this is the case6,9. Your physical therapist will be able to determine an individualized program based on your individual needs, but climbers in general can benefit from neck stabilization exercises. I’m sure I wouldn’t have to look hard to find a fellow climber that has experienced ‘belayer’s neck’. Even on the wall, climbing requires a large amount of repetitive neck extension and rotation at end ranges in order to read the route. One of the lowest hanging fruits for climbers, whether they have suffered a concussion or not, is to wear belay glasses. This will take a lot of unnecessary strain off of your neck, as hanging out in extreme neck extension session-in and session-out can lead to stiffness in the muscles at the base of your skull and instability in the deep muscles in the front of your neck, which tend to be weak on most people to begin with. This imbalance between the extensors in the back and deep flexors in the front can contribute to joint stiffness, pain and injury on its own, and will only serve to exacerbate or perpetuate post-concussion neck pain and headaches. Additionally, research has linked neck stability to decreased concussion risk, so having a strong healthy neck should be something all climbers take seriously. Neck stabilization exercises are therefore something climbers can use to assist with post-concussion neck pain and also help prevent future concussions4.

The deep neck flexors (DNFs) are the equivalent of the core for the neck. These small muscles counterbalance the larger extension muscle in the back of your neck. The neck extensors tend to get stiff from being constantly contracted either by constantly looking up while belaying or sitting at a desk with a forward head posture for long periods of time. Deep neck flexor training has been shown to help treat and prevent headaches and neck pain. You can test the endurance of your DNFs by performing the Neck Flexor Endurance Test. You’ll need someone to time and watch your neck for you to let you know if you fall out of position.

To perform the test, lay on your back with your knees bent and perform a chin tuck (think of giving yourself a double chin). Maintaining this position, lift your head about 1 inch off the surface. Hold this position, having your partner make sure the fold in your neck don’t separate. The hold time for persons without neck pain was found to be 39 seconds for men and 29 seconds for women2.

To improve the performance of the DNFs, you can start with basic chin tucks and progress to chin tucks with head lifts. Perform 2 sets of 10-12 reps of 10 second holds. You can do these every day, but aim to perform them at least 3 days out of the week for at least 2 weeks before progressing.

As these get easier, you can progress to the more advanced neck stabilization exercises. You’ll need a resistance band, click here to order a set from amazon. Start sitting in a chair with back support and progress to sitting without support or on a physioball, and finally, to standing. Place the band around the back of your head (at the base of your skull), and hold it in front of you, placing some tension on the band. Perform chin tucks as above. You can also train neck stability from multiple directions this way, by changing the position of the pull of the band.

Another potential contributing factor to post concussion neck pain and headaches is vestibulo-oculomotor dysfunction. If you are experiencing blurred vision or dizziness with head movements or moving visual environments, working with a therapist who has training in vestibular assessment and rehabilitation is important. The proper treatment will depend on the specific vestibular or vestibulo-ocular impairment you have and therefore will need to be individualized in order to be effective. In general, this treatment will involve either what is called adaptation or habituation, with the goal of re-acclimating your vestibular system through graded exposure, and could include exercises that combine head movement with focusing on a target or repeating movements that aggravate symptoms in a systematic way. Hand-in-hand with dizziness, you may be experiencing problems with balance and coordination after a concussion, which, if persistent, can benefit from balance and coordination rehabilitation training. Climbing is a sport that requires high levels of balance and coordination, so an effective program will start with general training and progress to climbing specific drills on the wall. This is where having the help of a climbing physical therapy specialist can be extremely helpful.

Last but certainly not least, aerobic exercise is a cornerstone of post-concussion recovery and return to sport. There have been numerous studies showing that performing consistent light to moderate aerobic after suffering a concussive event contributes to faster recovery and return to sport. As mentioned above, concussion guidelines recommend a brief 24-48 hour period of initial rest followed by and gradual and progressive return to activity and sport. However, a recent study out of Toronto found that beginning aerobic exercise even within 24 hours of injury is not only safe, but was associated with even faster recovery times and decreased risk of prolonged symptoms in athletes7. This was true even for those that were experiencing symptoms during daily activities at the time. While determining the optimal types of aerobic activity, intensity and duration still needs more research, the study used the following progressive stationary bike program:

Start with 15 minutes at a heart rate of at about 50-60% of your maximum heart rate. To calculate your max heart rate, the most precise equation is 211 – 0.64 (Age). Do this for 2 days, and if you are tolerating it well, bump the time up to 30 min for the next 2 days. If that goes smoothly, do 2 days of 30 min at 65-70% of your max. Finally, once you’ve done at least 2 days at that intensity, you can try 30 min of 1 min sprints every 5 min. Just like with the return to climbing program, if the next stage provokes symptoms, go back to the previous stage for another 2 couple days and try again.

While recovering from a concussion can be frustrating and even overwhelming, rest assured that if you are patient, and listen to your body, and are smart with your recovery, you can get back to climbing and other activities you love. The body has an amazing ability to heal if given the proper conditions, and there is good evidence to support the above recommendations for promoting recovery and returning to previous levels of physical activity. There are also many physical therapy clinics that offer concussion rehab programs and have providers that have training and experience working with athletes post-concussion. Don’t hesitate to seek out help from a qualified practitioner, and at the very least, see a provider to get screened and evaluated to rule out any serious complications. And avoid seeking the advice of the social media climbing community on this one, because concussions are complex and unique to each individual. We climbers are a tough crowd, sometimes to our own detriment, so it can be tempting to think we can handle it ourselves, but I can personally attest, that was my attitude and I could have saved myself a lot of anxiety and discouragement if I had seen my climbing PT sooner than I did. If you don’t know where to look, a google search of ‘physical therapy concussion rehab’ will usually produce good results in your area. If nothing is close by, one of the silver linings to come out of the pandemic is that physical therapists have gotten a lot of experience working with patients remotely. So don’t let location limitations stand in the way of quality care, finding a therapist you trust can make an invaluable difference in keeping you active and climbing for years to come.

Autor Bio

Stacey is in her final year as a doctorate of physical therapy student at California State University Long Beach. She is also a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist and former Certified Personal Trainer through the National Academy of Sports Medicine. She has been empowering clients to move better and stay active for 6 years and has worked at luxury facilities such as Equinox Fitness Club, as well as will private clients. Her professional interests include sports orthopedic physical therapy and opening a niche climbing and mountain sport physical therapy and performance practice. She took up rock climbing in 2019 as an outlet during physical therapy school and quickly fell in love. Besides climbing, she is an avid snowboarder and enjoys resistance training, yoga, hiking, scuba diving, traveling and spending time with her husband and two dogs. She recently developed a strong interest in concussion rehab after suffering a concussion herself and would like to give a special thanks to John Huang, PT, DPT, a climbing specialist and owner of The Climbing Clinic in Costa Mesa, CA, whose expertise and support was integral to her full return to climbing.

Research Support

1. Climbing Escalade Canada. CEC Concussion Protocol. Available at: https://www.climbingcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CEC-OP-08-Concussion-Protocol.pdf.

2. Domenech MA, Sizer PS, Dedrick GS, McGalliard MK, Brismee JM. 2011. The deep neck flexor endurance test: Normative data scores in healthy adults. PM & R, Feb;3(2):105-10

3. Ellis MJ, Cordingley D, Vis S, Reimer K, Leiter J, Russell K. 2015. Vestibulo-ocular dysfunction in pediatric sports-related concussion. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 16:248-255.

4. Fisher, J.P., Asanovich, M., Cornwell, R. and Steele, J. 2016. A neck strengthening protocol in adolescent males and females for athletic injury prevention. Journal of trainology, 5(1), pp.13-17.

5. Gurley JM, Hujsak BD, Kelly JL. 2013. Vestibular rehabilitation following mild traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 32:519-528.

6. Hrysomallis, C., 2016. Neck muscular strength, training, performance and sport injury risk: a review. Sports Medicine, 46(8):1111-1124

7. Lawrence DW, Richards D, Comper P, Hutchison MG. Earlier time to aerobic exercise is associated with faster recovery following acute sport concussion. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0196062.

8. McKay S. Imagine this: Mental Imagery strengthens neural circuits. Dr Sarah McKay. January 29, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://drsarahmckay.com/imagine-mental-imagery-strengthens-neural-circuits/

9. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, M Aubry, Bailes J, Broglio S, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):838-847.

10. Quatman-Yates CC, Hunter-Giordano A, Shimamura KK, Landel R, Alsalaheen BA, Hanke TA, McCulloch KL. Clinical practice guidelines: Physical therapy evaluation and treatment after concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. JOrthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(4):CPG1-CPG73. doi:10.2519/jospt2020.0301

11. Sheehusen CN, Mucci V, Welman KE, Browne CJ, Feletti F, Provance AJ. Review on reported concussion, identification and management in extreme sports. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2020;10(2):290-299. doi:10.32098/mltj.02.2020.14

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.