Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in Climbers

Icy wind, sheer exposure, and 207ft of vertical granite are below you as you lock onto a flake with your right hand and reach desperately for the next hold while your big toe feels dangerously close to losing that sweet friction of the rock. You strain your neck and look up above at your next move. You start to feel numbness and tingling down your right arm and are trying to fight the pump in your forearms. Breathing is strained and your shoulders are up to your ears. With that last ounce of strength, you push hard against the flake, and jam your left hand into the crack, safely clip in, and finish the second pitch. Years of coming to this route and you finally finish it! However, you shake out your arm and the numbness persists. The rest of the day, climbing just makes it feel worse. You start to feel right shoulder pain that stays… for days. You wake up with dull, gnawing, and tingling pain in your neck, shoulder, and arm. You go to sleep with it, and figure it’ll just go away but then you just can’t seem to shake it. Your neck and shoulder are on fire! What is going on?

Overview

You may have something called Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS). TOS is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning there can be other causes of pain and numbness, such as cervical radiculopathy or other nerve entrapments, that may not be due to true TOS. TOS is a compression of the brachial plexus (nerves), subclavian artery, subclavian vein, or a combination of the above.

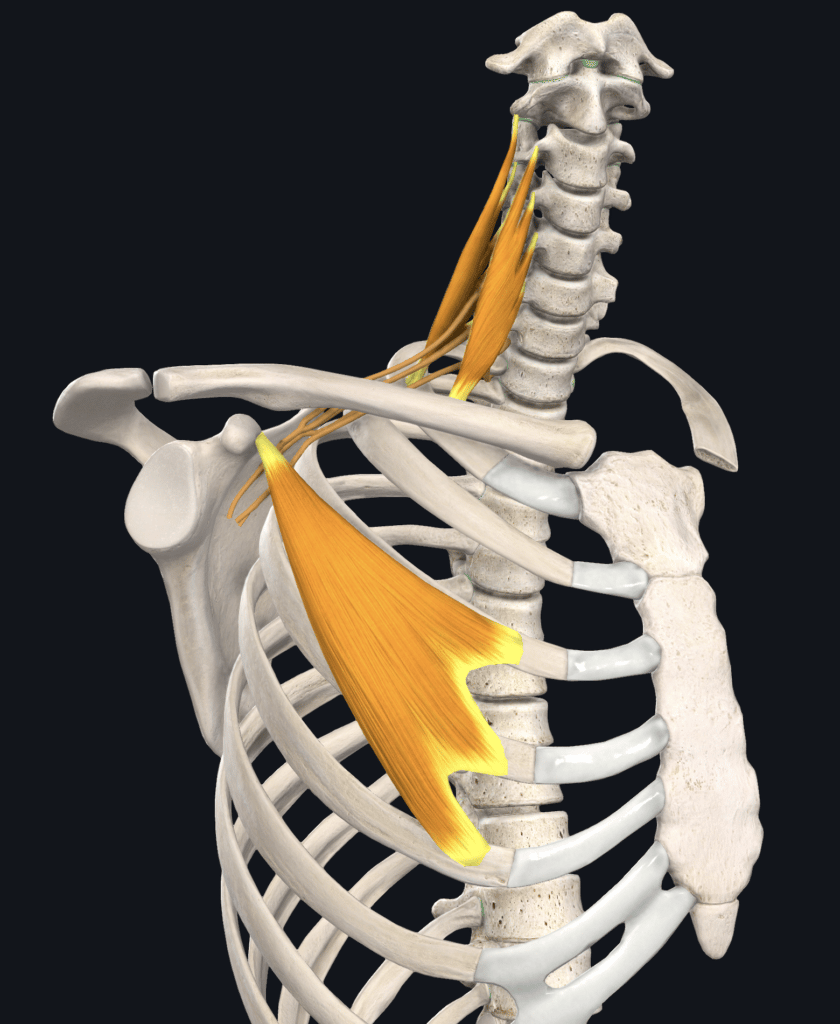

There are two main types: vascular (arterial or venous) and neurogenic, with 90% of TOS occurrences being neurogenic. There are three areas where TOS can occur: the interscalene triangles (between the middle and anterior scalenes with the first rib as the inferior border), the costoclavicular space (below the clavicle and above the rib), and the pectoralis minor space (between the coracoid process, pectoralis minor, and ribs 2-4). See image below.

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

TOS can arise from congenital abnormalities (presence of cervical ribs, or anomalous first ribs), trauma (due to whiplash injuries or falls), or it can be functionally acquired (with vigorous, repetitive activity associated with overhead sports, such as climbing). Symptoms include upper extremity paresthesias, trapezius pain, neck pain, shoulder and/or arm pain, supraclavicular pain, chest pain, or occipital headaches. If you see shoulder/arm discoloration, have increased warmth, or increased coolness in your shoulder/arm, or if you have deep chest pain, it is important to contact a medical professional immediately, since the symptoms, however rare, could be due to a life-threatening venous or arterial insufficiency (Hooper et al).

Assessment

Clinical tests to rule in or out the possibility of TOS have a potential for high false positives (meaning they can be positive in people without the condition) so tests should be completed in clusters to give better diagnostic information.

The tests include:

- Elevated Arm Stress Test (EAST)

- Supraclavicular pressure (SCP)/Brachial Plexus Compression Test

- Costoclavicular maneuver (CCM)/Military Brace Test

- Adson’s Test

- Wright’s Test

- Cyriax Release Test

Two positive tests have a combined sensitivity of 90%, while five positive tests increase the specificity to 84% for TOS (in statistics, high sensitivity is helpful for suggesting you cannot rule out TOS as a diagnosis, and high specificity is helpful for ruling in a diagnosis. Ideally, you want both numbers to be as high as possible to help you come to a conclusion on your what your impairment might be) (Gilliard et al).

Elevated Arm Stress Test

Supraclavicular Pressure Test

Costoclavicular Maneuver

Adson’s Test

Wright’s Test

Cyriax Release Maneuver

Another potential impairment is a nerve entrapment at one site, or a “double crush” nerve entrapment which refers to neural restrictions in two or more places. Double crush diagnoses can include TOS but they don’t have to. In any case, climbers may be more prone to TOS or other nerve entrapments secondary to participating in a vigorous overhead sport that requires constant arm elevation (almost perfectly describing the EAST test for TOS). They can suffer from whiplash due to falls from high places, causing cervical muscle stiffness. They can have hypertrophy (increased mass) of the pectoralis minor and/or scalenes due to overutilization of pectorals for gripping juggy holds, or due to overutilization of neck muscles for breathing in stressful situations (200ft in the air at the crux of a problem), leading to compressed neurovasculature and TOS.

Standing posture should also be observed, noting that TOS is more prone in those with rounded shoulders, forward head positioning, protracted and downwardly rotated scapulae, inadequate thoracic extension, or inadequate clavicular mobility (Hooper, et al).

Forward Head Posture

Ideal Posture

Next, the person should be observed while climbing, noting reproduction of the above impairments, excessive upper trapezius activation, chest breathing, weakness or poor motor control of scapular retractors, or over-utilization of pectoralis minor.

A good physical therapist or movement specialist could help to correlate movement patterns with the person’s primary complaint to determine the most aggravating activities. These people may benefit from strength testing, manual therapy, as well as with specially crafted exercises to work towards reintegration to climbing with movement modifications to decrease symptoms.

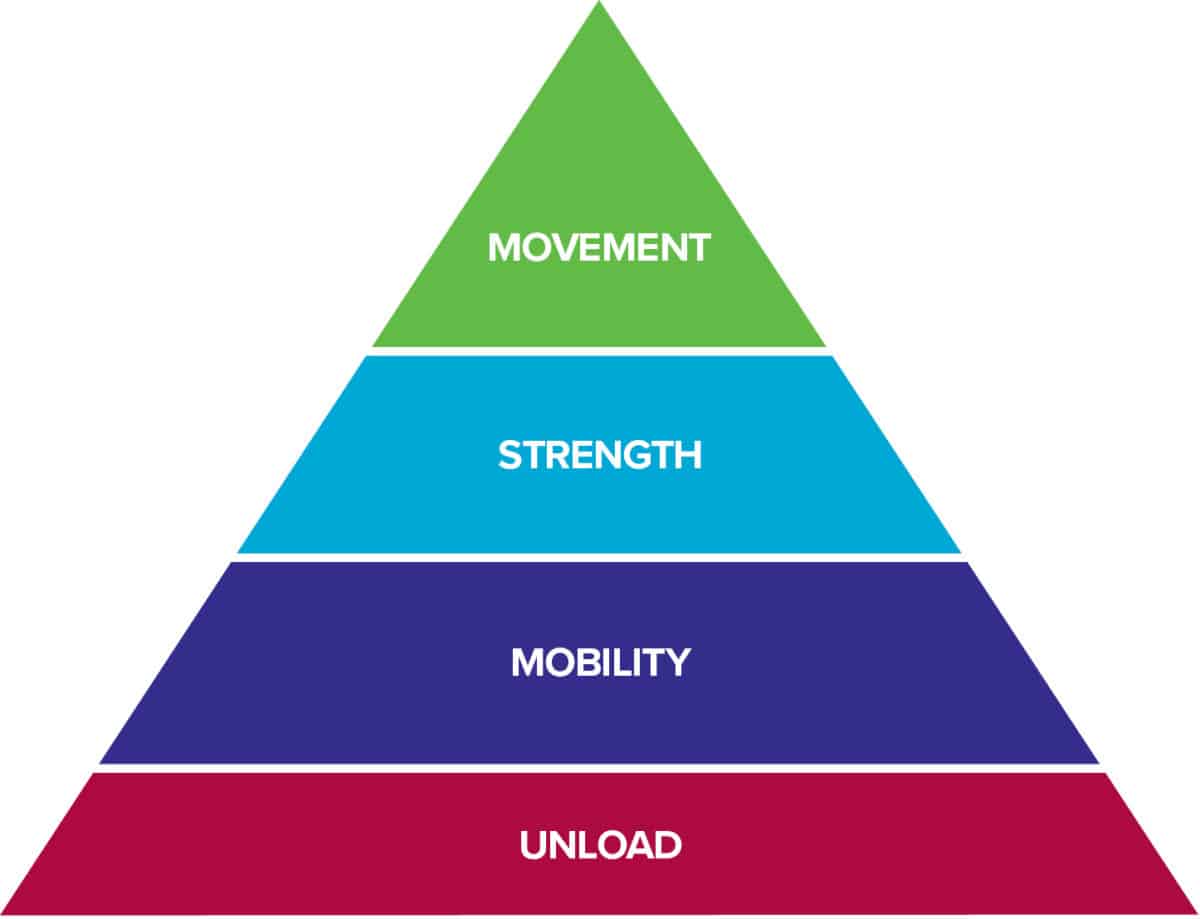

The Rock Rehab Pyramid

Now that you have determined how to assess for injury, you can now intervene with a systematic intervention program to help you manage your symptoms and ultimately get you back on the wall. In order to ensure a safe and pain free return back to rock climbing, we will be utilizing the Rock Rehab Pyramid developed by Dr. Jared Vagy and illustrated in his book Climb Injury-Free. The Rock Rehab Pyramid pyramid allows you to self-gauge your injury and when to progress to the next stage of recovery starting with the unloading phase moving to mobility, followed by strength and lastly the movement phase.

The bottom level of the pyramid aims to decrease Pain, Inflammation and Tissue Overload so that the tissues have the best healing environment. Often times, after an injury there is some sort of change in Mobility. After the tissues have calmed down from the previous level, this stage will look to reestablish normal, pain free range of motion. Once the injured area restores its mobility, it is time to increase the Strength of the surrounding muscles so that Movement in the following level can be coordinated and optimized. Click here to learn more about the rock rehab pyramid structure.

Treatment (4 Phases)

All right, so you think you have TOS? Follow these exercises to help you recuperate so you can regain your strength and confidence to conquer your tough problems again!

Phase 1 (Unload)

Cyriax Release Maneuver: If you can afford to take a brief hiatus from climbing, it may be the best course of action to promote tissue healing since the structures involved (often times nerves) are easily aggravated and can stay aggravated for long periods, and can even worsen if unloading is avoided. During this time off from climbing, it is important to further offload the neurovasculature for as long as you can by simply sitting with your arms propped on multiple pillows placed under each forearm on armrests. This decreases the strain on all three compartments that are associated with TOS: the interscalene triangle, the costoclavicular space, and the thoraco-coraco-pectoral space (pectoralis minor space). It is an easy maneuver that allows healing to occur at the nerves and blood vessels because it slackens tight muscles and decreases the potential compression at the bones. If you are not near a chair and pillows you can also rest both hands on top of your head while keeping your shoulders down (don’t let them elevate towards your ears).

Unloading Option 1

Unloading Option 2

Phase 2 (Mobility)

Part 1: First Rib Self-Mobilization: Take a belt and loop it around the shoulder of your affected arm, then sit on one end. Pull the other end taut with the other hand. Hold for 10-30 seconds at a time, then release. Perform this as many times as you can per day as long as it does not increase tingling. You may feel a stretch in your neck muscles. This helps to improve the first rib mobility in climbers especially if their neck muscles are tight and are contributing to the TOS symptoms. If you are able to tolerate this without too much discomfort, try adding a slight head bend away from the belt to further stretch your scalene muscles.

Part 2: Median Nerve Glides: Once your tight muscles have calmed down a bit, it is important to start improving your nerve mobility by gliding the nerves under the musculature and structures that may have compressed it. With nerves, it is important to pay special attention to pain and keep all movements within a pain-free range. The phrase “push through the pain” does not work well with nerves, as pain may mean more damage to these sensitive structures. Stand and elevate your involved arm 90 degrees to your side (abduction) while keeping your elbow straight, while keeping your palm up. Bend your wrist down (extension) while side-bending your neck towards the arm, then bend your wrist up (flexion) while side-bending your neck away from the arm. Do these exercises 15×3 times per day, as long as you have no pain/discomfort, to improve median nerve mobility.

Median nerve glides

Ulnar nerve glides

Part 3: Ulnar Nerve Glides: Start by bending and straightening your elbow. If you experience no discomfort, you can continue. Make an “okay” sign with your thumb and first finger. Now, straighten your elbow and bend your neck towards your affected shoulder, then bend your elbow to the side while gently bending your neck away from the moving arm as long as you have no pain. Repeat 15x, 3x per day to improve ulnar nerve mobility.

Part 4: Cervical Side-bends: This is a relatively easy exercise to stretch muscles that are likely tight and contributing to your TOS symptoms. Place your left hand on your right shoulder and “pin” down your shoulder. Now slowly bend your head to the left. Hold for 30 seconds. Repeat 3x, then do the same to the opposite side.

Part 5: Chin Tucks/Cervical Retraction: This can be a challenging exercise because it is pretty specific. The goal is to bring your head back over your shoulders and make a double chin. If you can achieve this, it may feel pretty weird but it is the key to improving your neck posture to decrease excessive neck activation. Try this sitting or standing first. If you can create a nice double chin pretty easily, progress the difficulty to doing it while lying flat on your back. Bring your chin back towards the floor. Hold for 10 seconds and relax. Try to do this without activating the thick neck muscles (sternocleidomastoids) on either side of the neck. If you are able to lay on your back and lift your head up while keeping the double chin, lift your head off the floor for 5 seconds. The second you start to lose the folds in your neck or when you start to feel those side neck muscles come on, bring your head back down. Your goal is to be able to do 10 repetitions of 10 second holds without pain. These can be tougher than they seem!

Chin Nod Part 1

Chin Nod Part 2

Part 6: Scapular Retraction: If the above is pain-free, you can move onto part 3. Try this sitting at first. Gently squeeze your shoulder blades together, then relax. If this causes no pain/aggravation, repeat 10x with 10 second holds. This helps actively stretch the pectoralis minor which is also often implicated in TOS pain. It also helps to strengthen the antagonistic muscles- the middle trapezius and rhomboids, which can improve climbing posture and are important for regaining the scapular strength you will need to crush your next projects.

Scapular retraction

Phase 3 (Strength)

Part 1: Prone Shoulder Horizontal Abduction (T’s): All right, now we are moving on up in the world of rehabilitation if you have reached this phase, pain free. You should spend a while with the above exercises and make sure they are not making your symptoms worse. If so, then take it down a notch by regressing to the previous exercise. Coming off of injuries is hard, but try not to push too hard too fast, or it may increase the healing time needed. This exercise works your rhomboid muscles. For the prone shoulder horizontal abduction, lay on your stomach on the ground. Start with your arms stretched out to your sides, touching the ground. Now, while keeping your chin tucked, gently squeeze your shoulder blades together and allow your arms to lift off the ground. Relax your arms back down. Repeat this until fatigue, or until you start feeling pain, or excessive shoulder muscle activation. You should feel this exercise mainly between your shoulder blades, but this can be an aggravating maneuver for TOS. If this is challenging, you can bend both elbows to decrease the lever arm on both sides.

Part 2: Prone Shoulder Scaption (Y’s): Laying on the ground, bring your arms overhead, into a “Y” formation, while bringing your hands so your thumbs are facing upwards. This works on your lower trapezius to improve your ability to reach overhead while climbing without increasing the strain on your upper shoulder muscles. This exercise also helps to stretch your pectoral muscles actively to decrease compression in the front of your shoulder which may be the culprit of your TOS symptoms.

Prone T’s

Prone Y’s

Part 3: Bruegger’s Wrap Lateral Walks: The set up for this exercise can be a little difficult but nothing you can’t figure out (check out the video for visual aid). It requires the use of a long resistance band, so see if you can score some. Have a seat and bring your legs and feet together. Take the middle part of a 10ft resistance band and wrap it once around your feet, then make a cross over the front of your shins with the band. Next, cross the band behind your knees, then hold each end of the resistance band in each hand. Now, separate your feet, knees, and arms while keeping your elbows bent, and pointing towards the ground. Check your neck posture to make sure you are doing a slight chin tuck (described above). Now, stand up. Squat while keeping your hips behind your knees and your knees directly over your toes. Finally, take some steps (try 10 steps) to the left while maintaining this position. Stand and rest. Now get back into that squat hold and take 10 steps to the right. This exercise is good for activating antagonistic postural muscles in your back and shoulders (as well as gluteals) that may be underused due to your painful symptoms.

Bruegger’s Wrap Lateral Walks

Phase 4 (Movement Exercises)

Part 1: Start in the gym: You are now ready to get back at it and start vertical climbing. If you boulder, try starting with V0s and keep using mostly your legs for the climbs. Try and keep your neck in a neutral position, using the “chin tuck” method you learned above and keep your body close to the wall to decrease the potential for neck and shoulder strain. Remember to take deep breaths throughout so you can keep your neck muscles relaxed. Slowly work up to V1s, V2s, etc. Make sure you do this as a warm-up for all your bouldering sessions so you can give your muscles a chance to warm up and decrease the risk of injury with climbing using cold muscles. If you are top-roping, start at a lower level again then work your way up. The same principles apply.

Part 2: Wall Traversing: Okay, if you’ve been able to complete all the above, pain and symptom-free, you are ready to get back to the wall to do some mild traversing! During this time try and maintain a slight chin tuck when you can, and keep your body close to the wall as above- extra points if you can squeeze your shoulder blades gently when your arms are not overhead. Concentrate on taking deep breaths from your abdomen, relaxing your neck muscles, and using your legs for 80% of the work, while practicing weight-shifting, initiating with leg movement versus arm movement. Climbing should be predominantly a leg exercise if you are doing it right. Save your arm strength for when you need it and use your legs as much as you can to increase endurance.

Wall Traversing

Part 3: You are ready to get back to more challenging or outdoor climbs! Keep that relaxation you felt previously, try to keep your chin tucked as often as possible, and keep your shoulder blades engaged unless you have brief moments that require you to bring your shoulders forward. You should be able to maintain a gentle shoulder squeeze throughout most of your climb, unless you are reaching overhead, which may help improve your grip strength. If you have any questions, contact myself or a physical therapist who is knowledgeable in rock-climbing so we may do a video-analysis of your techniques and offer more specific suggestions to your style of climbing. If the pain or symptoms worsen, it may be time to see a medical doctor so you can get appropriate imaging and treatment.

See a Medical Practitioner

There are many causes of shoulder pain, and numbness/tingling. Some conditions, as mentioned above, can be life-threatening especially if you experience deep excruciating pain, temperature changes, or swelling in any part of your body. The information in this article should serve as a guide, but may not necessarily apply to your specific case. If you are worried about serious injury, please see a local physical therapist or other medical practitioner who can uncover any underlying impairments and provide an individualized plan of care.

Meet the Author

Gail Skoropad, PT, DPT is a doctor of physical therapy and graduate of the University of Southern California school of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy. She received her bachelor of science degree in biological sciences at the University of California at Irvine. Currently, she works in Laguna Hills at Complete Balance Solutions where she treats patients with vestibular, balance, as well as orthopedic disorders. On the weekends, she mainly boulders in the climbing gym or locally outside. She also likes to hike, dance (salsa and bachata), as well as play French Horn and listen to all kinds of music. If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to connect with her at gsuchoknand@gmail.com.

References

- Gillard J, Perez-Cousin M, Hachulla E, Remy J, Hurtevent JF, Vinckier L, et al. Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome: contribution of provocative tests, ultrasonography, electrophy- siology, and helical computed tomography in 48 patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2001;68:416–24.

- Hooper TL, Denton J, McGalliard MK, Brismee JM, Sizer PS. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. J Man Manip Ther. 2010;18:74-83.

- Hooper TL, Denton J, McGalliard MK, Brismee JM, Sizer PS. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. 2010 VOL. 18 (3):132-138

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

I’m so glad to have finally found good information on this. I’ve been climbing for about 6 years now but about two years ago I got a blood clot from overhead shoulder overuse (a doctor mentioned TOS). Eventually that went away after taking blood thinners but pain and swelling persisted when I climbed very hard. Despite this, I wasn’t about to give up on climbing, however, the vascular surgeon I went to suggested nothing besides just dealing with it or having TOS surgery (removing the first rib and whatnot). So here’s to finally having an actual exercise regiment to work on!

Hello Stefan, I am new to the party, got a clot s month ago. Mine is a vein clot, yours too?

Did you monitor clot progress/”dilution” with ultra sound? How long did it take to for away? It seems that something is left though.

Would like to know your age and progress (I am 57).

Did you experience pain of any kind, before or after?

Hello Gail , thanks a lot for the info. I will certainly try (under my doctor’s consultation).

I have a problem though: mine is a vein clot/TOS and I have no pain (just arm swelling after any exercise).

Most of them exercises and progress suggested work in a trial and error situation at the pain limit, suitable for neural TOS.

Is there a work around for no pain / vein TOS?

How to check if there is harm instead of good?

If Venous or arterial TOS it is recommend for your physical therapist to use a Doppler during exercises to monitory vascularity in addition to symptoms. That way you know whether or not you are changing blood flow.

Hi ! Thanks for the niformation. How do you know when you can go from first phase (unloading) to mobility? Do you need to be symptom free or just decrease in symptoms? Are there any other maneuvers or arm position to unload like the cyriax release or hands resting on head? Thanks

Typically 2 weeks is a good stage to transition from unloading to mobility.

Patients will often still have symptoms (although reduced) during the mobility phase.

For other scapular elevation unloading positions, you can try this progression: hands on the hips, arms crossed, hand on head, forearm resting on head.

However, as the arm goes higher over the head symptoms may increase.