Climbing Post Concussion

When one considers climbing, many images come to mind. Daring ascents up sheer faces, powerful moves off of razor sharp holds, sleeping beneath the stars on a narrow ledge balanced precariously over the open air. When a climber is uninjured and in top form, the world is without limits.

However, to the injured climber, these possibilities seem to shrink to a pinprick. A small bead of light in what can sometimes seem like endless darkness. This is true for many forms of injury, and all the more so for injuries that affect arguably the most important organ of the human body.

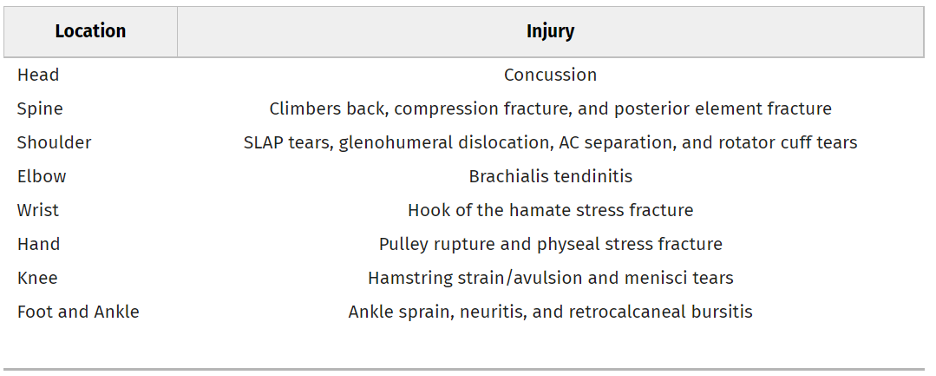

Concussions, which are considered to be a mild form of traumatic brain injuries, are the number one head-related injury within Rock-Climbing, accounting for up to 70% (Cole et. al, 2020; figure 1). Within the global population, an estimated 69 million people suffer a traumatic brain injury annually 2, while between 1.7-3 million sports and recreation related concussions occur within the United States each year (UPMC, 2022). Given these statistics, a staggering 86.9% of climbers have reported that they never wear a helmet when climbing (Keegan, Richard, Andrew, 2020).

Regardless of the cause of the concussion, be it from climbing, a road accident, or some other athletic endeavor, the presence of the injury can be fiercely prohibitive to one’s climbing. Below, we will discuss what you should do when you suspect you have a concussion and the appropriate steps to take, during, and after, your initial injury. The good news is, return to sport after a concussion is absolutely possible, given enough time and work is put into proper recovery.

Figure 1. Cole et al. 2020. Most common injuries by body location during climbing.

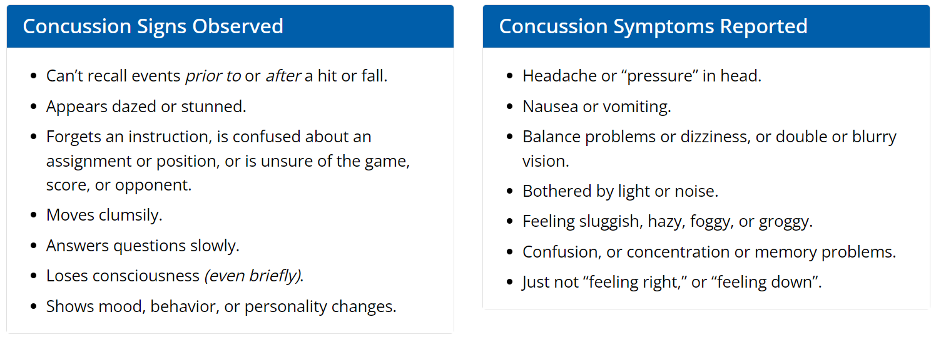

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of a concussion will vary depending on the severity of impact, though it will almost always be preceded by a blow to the head of sufficient force. This can occur secondary to a fall from height, or a blow to the head by a falling object (often a rock, termed a “rockfall”) or another person.

The most common signs, both reported by the athlete, and observed by others, are listed below.

Figure 2. Observed and reported signs and symptoms of concussion (Center for Disease Control n.d.)

Should any of the above-mentioned symptoms be present after a blow to the head, it is important to seek medical attention as soon as possible. Untreated concussions, or concussions that are severe enough, can lead to permanent disability or death if proper medical care is not administered.

Assessment

There are several assessment tools used to assess for a concussion, depending on where the assessment is being performed. The SCAT5 is a comprehensive tool designed for the detection of concussions in a sport setting and was initially designed for use on-field as an initial screen to be performed by a trained medical professional. Positive results on this assessment are used to refer a patient for medical care.

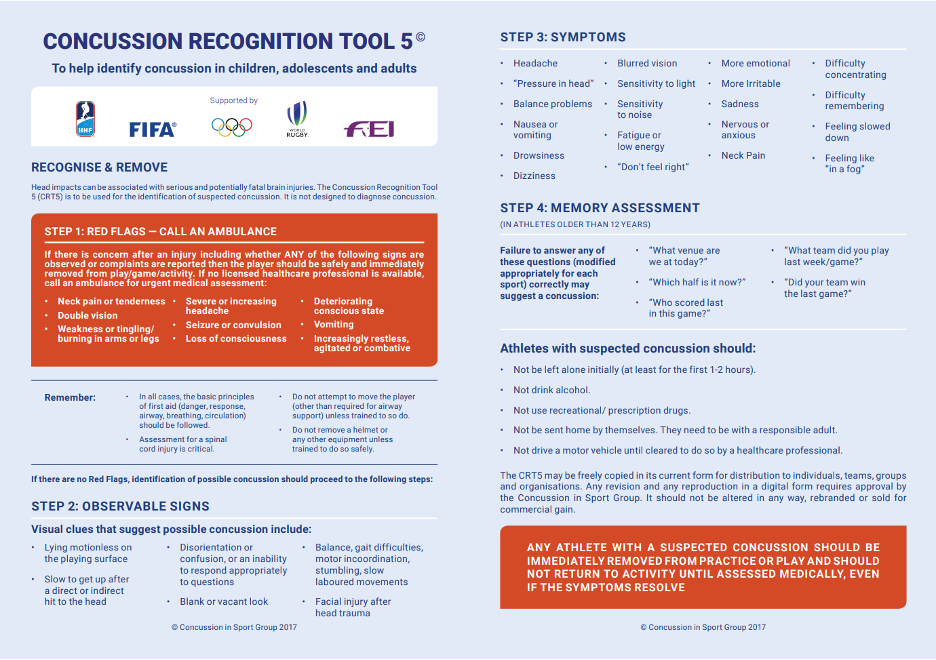

However, for those not formally trained as a medical professional, or those with no experience using the SCAT5, there is instead the Concussion Recognition Tool (CRT5). This is designed for use by anyone present with the injured athlete, and lists red flags, observable signs, athlete symptoms, and a memory test which is easy to administer. Should they be positive for any of the signs or symptoms, especially the red flags, or should they fail to complete the memory assessment, then medical care is needed.

But remember, some concussion symptoms don’t appear immediately. If there is any concern that the athlete has taken a significant blow to the head, it is better to use caution and stop climbing. If, after 48 hours no symptoms have appeared, it would be safe to return to the wall.

Figure 3. Concussion Recognition Tool 5 (Concussion in Sport Group, 2017).

Once a concussion has been diagnosed and a physician has given the all-clear, active rehabilitation can begin. It is worth mentioning that up until recently (the last decade or so), rehab for a concussion was predominantly “rest”. The research has now shown that active recovery leads to much better outcomes, and a lack of activity can in fact increase the risk of post-concussion syndrome.

At this stage, it will be important to visit a qualified Physiotherapist or medical professional with experience in the treatment of concussions, as they will be able to help to assess and understand which symptoms are present, in order to prescribe adequate treatment techniques.

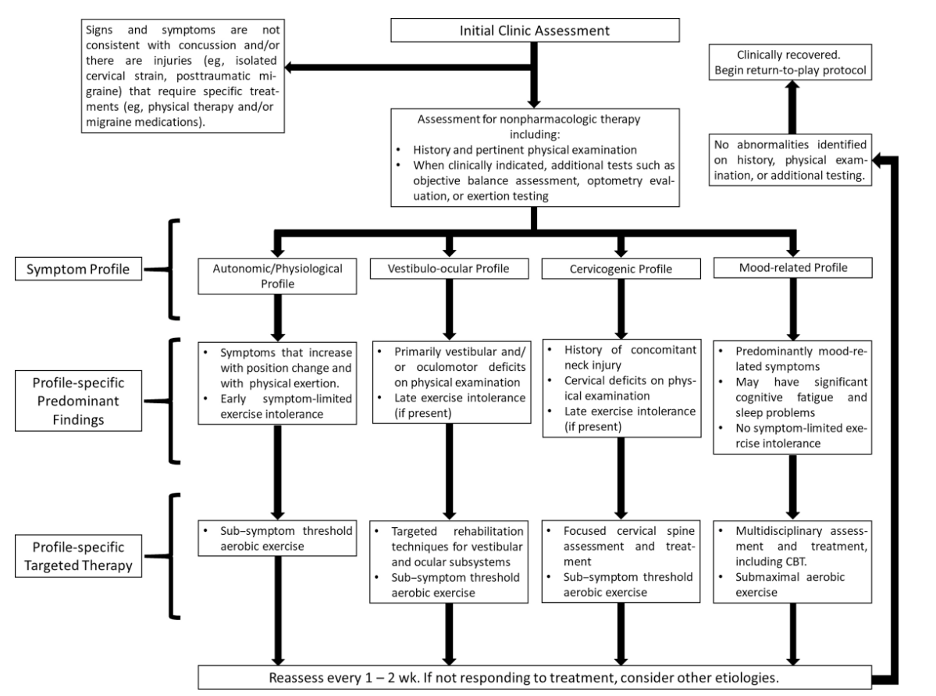

The reason for this is that every concussion presents differently. Generally, the symptoms are categorized into: anatomical/physiological, vestibulo-ocular, cervicogenic, and mood-related (Haider et. Al, 2021). These are presented in Fig 4, included below.

To Summarize

Anatomical/physiological symptoms are related to one’s physical performance. Indicated by increased fatigue and poor response to physical activity.

Vestibulo-ocular symptoms are related to the functioning of the eyes, and the neural networks associated with controlling the eyes and interpreting visual information. Presenting as an impaired ability to focus one’s vision, dizziness with movement, and poor eye tracking, among others.

Cervicogenic symptoms are related to the cervical region of the neck. This is the uppermost section of the spinal cord, approximately between the base of the skull and the shoulders. Symptoms here include neck pain, headaches, and loss of range of motion.

Mood related symptoms include changes to mood post-concussion and are the one category listed here that is not addressed through physical therapy. Instead, these should involve a consultation with a mental health professional.

Figure 4, as mentioned, details the flow and subcategorization of symptoms from a concussion. This table may seem confusing, and that’s ok. It simply serves to highlight the differences one can see, clinically, when assessing a concussion. This is what your Physical Therapist will be doing during their assessment.

Figure 4. Clinical management of concussion profiles (Haider et. Al, 2021)

Treatment

Once an assessment has been completed and the specific symptom presentation has been identified, a rehabilitation protocol can be designed by your Physiotherapist. In order to properly understand the symptoms, and correctly target treatment, a proper assessment is important.

Generally, strength training is not advised initially as wild swings in blood pressure can put unnecessary strain on the concussed brain. Also, activity recommendations are for activities that are performed in a stable position, to minimize unnecessary head movements. Activities that put the athlete at risk of re-injury, be it from sudden rapid head movements, or further blows to the head, should be avoided until symptoms resolve. This does, unfortunately, mean that a break from climbing will be necessary initially.

Below is a collection of exercises that can be done to help address some of the possible symptoms as described by Haider et. Al (2021), as well as recommendations for a return to sport timeline, and supplemental activity guidelines.

Occular

Repetitive Saccades: Place two targets (e.g., post-it notes) on a surface 0.5m apart horizontally and vertically, and stand 0.5m away. While keeping the head still, look back and forth between each target. Start with the number of repetitions needed to elicit symptoms, plus 3 more. This will help to increase your stamina. Begin horizontally, working up to one minute while taking breaks whenever you reach the symptoms + 3 threshold. Perform 1 minute vertically as well, following the same guidelines.

Static Fixation: Take a string, and place beads at three places along the string: one at each end, and one in the middle. Hold the string so that one bead is as close to the nose as possible while still being in focus, and the string is perpendicular to the face. Then, look at the farthest bead, the middle bead, and the closest bead one after the other. Each bead should be kept clear and in focus. The ultimate goal is to have the closest bead within 6cm of the nose without producing a double image (diplopia).

Vestibular

Gaze stability: Place a target on a stationary surface and focus the eyes on the target. Then, move the head from side to side and up and down while maintaining focus on the target. Move at as quick a speed as possible while maintaining focus and without blurring vision. The goal is to reach 2Hz, which is 2 movements per second.

Cervical

Treatment of cervical pain involves a tailored prescription of range of motion exercises, manual therapy, mobilizations, proprioceptive training, and exercises to strengthen some deep and superficial neck muscles. Generic exercise prescription is not advised for this.

Aerobic Exercise

Sub-symptom aerobic exercise is now strongly recommended in post-concussion treatment. This can be specifically tailored to the athlete, and adjusted throughout recovery. As a general rule, light aerobic exercise can be initiated soon after injury, and should be performed for a minimum of 20 minutes a day. As the name suggests, the exercises should be performed until symptoms begin to appear. As mentioned earlier, this is best performed on a stationary bike, in order to reduce head movement. Once at a stage where returning to the wall is safe, this can be supplemented with traverses and longer duration climbs, that are well below the athlete’s normal level. Research has shown that mild symptom exacerbation does not damage the brain or impair outcomes. However, high intensity exercise has the possibility of prolonging recovery (Maerlender et. Al, 2015). Further, in cases where a minimal amount of exercise provokes symptoms, rest is instead advised.

Returning to the Wall

A medical examination, either by a doctor or by a qualified physiotherapist, is important in determining if it is appropriate to return to the wall. In general, enough time must have passed for the athlete to be symptom free during activity. For some this could be a matter of days, for others much longer. The return to climbing will need to be done in a progressive manner, in order to monitor for symptom recurrence and properly build up tolerance.

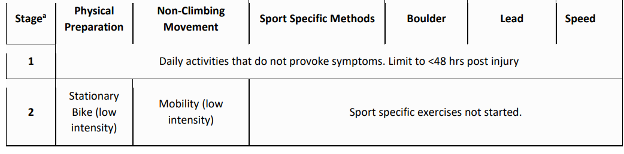

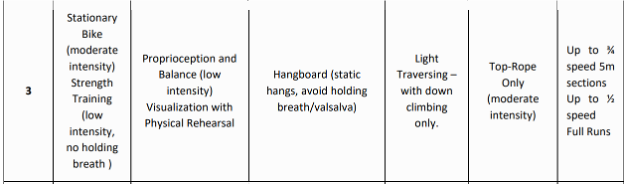

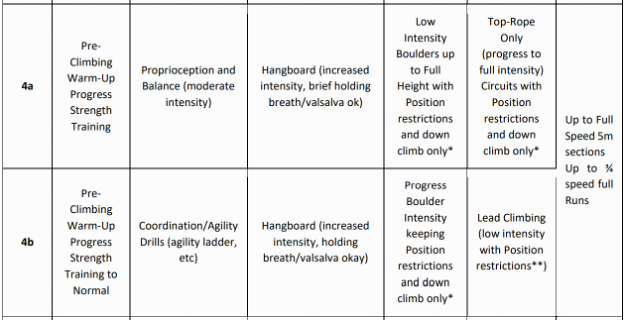

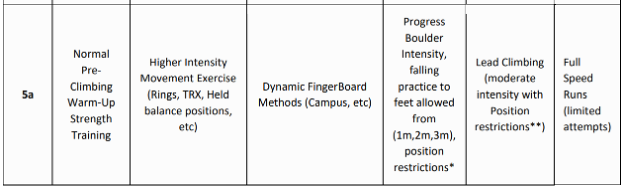

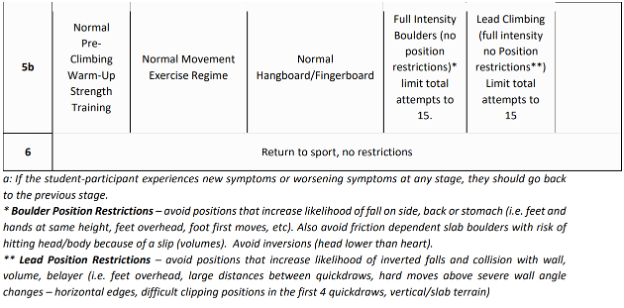

Climbing Canada has a multi-stage process for return to sport which has been included below.

They advise ensuring that the athlete is able to perform the activities described under each stage, without symptoms over a period of 24 hrs, before progressing to the next stage. If symptoms are present, return to the previous stage.

The above should serve as a rough guideline on how to understand and cope with a concussion. However, proper medical advice is critical. A doctor should always be consulted when a concussion is suspected, and a qualified Physical Therapist should always be involved in rehabilitation. This will ensure the correct symptoms are treated, and will result in the fastest, safe recovery possible.

The Author

Tristan Smith-Klooster is a registered Physiotherapist based in Montreal, Canada. He is currently working to specialize in the treatment of Climbing related injuries and cardiovascular conditions, as well as the treatment of concussions and TBI.

References

- Climbing Canada, https://climbingcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CEC-OP-08-Concussion-Protocol.pdf

- Cole, K. P., Uhl, R. L., & Rosenbaum, A. J. (2020). Comprehensive review of rock climbing injuries. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 28(12), e501-e509.

- Dewan, M. C., Rattani, A., Gupta, S., Baticulon, R. E., Hung, Y. C., Punchak, M., Agrawal, A., Adeleye, A. O., Shrime, M. G., Rubiano, A. M., Rosenfeld, J. V., & Park, K. B. (2018). Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurosurgery, 1–18. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352

- Haider, M. N., Herget, L., Zafonte, R. D., Lamm, A. G., Wong, B. M., & Leddy, J. J. (2021). Rehabilitation of sport-related concussion. Clinics in sports medicine, 40(1), 93-109.

- Maerlender, A., Rieman, W., Lichtenstein, J., & Condiracci, C.. (2015). Programmed Physical Exertion in Recovery From Sports-Related Concussion: A Randomized Pilot Study. Developmental Neuropsychology, 40(5), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2015.1067706

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.