Route Setting to Prevent Climbing Injury

Recently, “The Climbing Doctor” had the chance to connect with Chris Danielson, who is one the most renowned American route setters. This was a unique opportunity to see the behind the scenes thought processes that goes into competition route setting and how the same methodology can be applied to route setting for non-competition climbers in the gym . The thought process behind setting, how to normalize routes to be an equal challenge for climbers of different shapes and builds, and routesetting tips to limit injury were all discussed. Check out the interview to gain a deeper level of understanding for what goes on in the genius mind of a routesetter.

Introduce yourself and your experience climbing and setting?

Chris Danielson. I’m from NY originally and the first real climbing I ever did was one day of top-roping on an Outward Bound trip to the San Juan Mountains in Colorado almost 25 years ago. I came home, bought a rope, some webbing to make harnesses with and started going out with friends, mostly rappelling down dirt cliffs, and trying to climb back up them. Bored on suburban evenings, we would go to a Blockbuster video store at a local shopping center, rent some movies, and wait until they were closed so we could traverse back and forth on the cobblestone exterior of the building. The first routesetting I ever did was really just on that wall, finding the challenges, strength and movement required, to move through eliminate lines of stones. I then went to college at Miami University in Ohio, started climbing regularly on the university wall, routesetting and working there within a few months, and took my first big climbing trips outdoors to the Red River Gorge and Hueco Tanks. I’ve been routesetting in some form or another ever since and over the last 10 years have spent most of my time with competition routesetting at the national and international level.

Chris Danielson. Photo Credit: Caroline Treadway

Describe the process of setting a route from start to finish?

It completely depends on the person and the setting scenario.

Competition routesetting has a focus to work towards dividing a field of competitors with the appropriate level and stylistic diversity based on the anticipated ability. For some setters, regardless of commercial or competition setting, it can be a very analytic or systematic process. You select all the holds first, imagine and mentally or visually structure the moves and placements, and then build the route based on thoughtful planning. For others, it is a much more organic process wherein you might begin with an idea at an arbitrary point in the terrain (whether the top, the middle, a certain feature or hold, etc.) and then just explore creative options from there. Sometimes this can be thought of as letting the route set itself, or “finding” the route through the process. It can often entail a lot of trial and error. After all the holds are placed, and thus the first draft or “skeleton” of the route is set, then the forerunning begins. Setters climb and climb again, make refinements, change sections to work towards the desired difficulty or movement or consistency or flow.

Commercial routesetting can have all of the same challenges and excitement, depending how one approaches it. But the key difference is just that the field is different. In competition setting your job is to imagine what a specific group or range of competitors may do, but in commercial setting the “field” can be anyone and everyone that might climb on the particular route or problem being set.

Chris Danielson Setting on Ladder at Movement. Photo Credit: Caroline Treadway

What excites you about route setting?

It is always a new challenge, mentally and physically, every time. I get just as excited creating from scratch as I do looking at a wall filled with holds and wondering whether or how one can go from hold x to hold y, and what the best body position will be, whether for myself, specific climbers, or what the most likely method may be for most climbers. All of this is a game of problem solving and creativity that is an endless playground for exploring movement. Even just the solitary mental exercises are exciting, but when setting for others, whether people in a gym or a very specific competitive field, the real excitement comes in seeing what the climbers do. It’s always fun to watch people move through choreographed sequences and assessing your own estimate of what might happen, but I’d have to say the most exciting moments come when a climber finds an alternative solution to what you may have anticipated, really demonstrating their own creativity and ingenuity. Since what you create is not for yourself but everyone else, the most rewarding experience is always in seeing the climbers interact with the questions you’ve posed to them, and if in the competition realm, how they engage with an audience and vice versa.

Alex Puccio solving the crux with planned body movement. Photo Credit: Angie Payne

How do you normalize a route to be an equal challenge for climbers of different shapes and builds?

This is a never-ending challenge. A main thing I focus on is trying to anticipate the extremes and working to create what we call equitable options for different climbers. The simplest example to think of is a 6’ 3” and 5’ tall climber. In competition, I want each of these competitors not necessarily to be able to do the exact same thing, but to have a relatively similar likelihood of completing the route, or if not the individual route – then a range of routes or problems that will balance the competition throughout a round.

The same can apply in the commercial realm. You may have routes that are better suited for really tall climbers of a certain level of ability, where perhaps some shorter climbers cannot even reach between the holds. If you like, in the forerunning, you might shorten the distance to make certain that the shortest climbers you anticipate trying the climb, can reach between the holds. Or, you might create alternative sequences that you imagine are possible, and of somewhat similar difficulty, for the different climber heights. But, even if you have one problem that might favor taller climbers, you might also have a problem where the holds are much closer together, or the body positions required are much more suited to smaller climbers, and you thus try to create equitable options for people of varying heights to accomplish similar goals – whether that be in terms of a range of difficulty in the gym, or a chance to succeed in competition. In comps, we generally try to ensure that the tallest climber cannot reach through and make something much easier than a shorter climber who cannot reach at all and has to jump. But, often times shorter climbers with a lower center of gravity and typically greater core tension, might find it easier to jump and hold a dynamic movement, than taller climbers may find reaching through and then holding and moving out of a static position. It really just depends on the circumstances. It’s all about finding a balance and there are countless ways to approach doing so but the first thing in one’s mind should be at least imagining the full scope of possible climbers and what options they may have, and then accommodating for the variables however you like and believe will accomplish your goals.

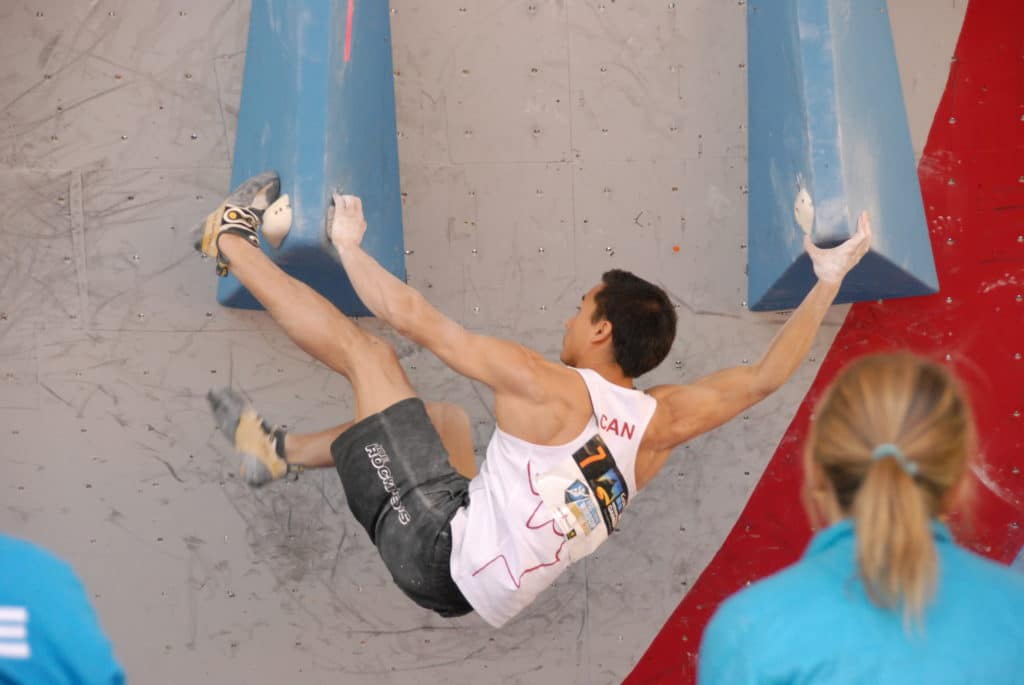

Sean McColl utilizing body positioning to solve the crux. Photo Credit: Terry McColl

What are some tips setting routes to limit injury potential?

Since climbing itself is such a creative act, with so many options for movement, routesetting is as well. Minimizing injury in the gym or competition environments alike, must involve good choices on both the part of the setter and the climber. In general, as climbing is of course a dangerous activity, we know that we can be injured in a variety of ways. For routesetters, one of the things we always want to consider is fall potential. Where will a climber fall when failing on a movement, what will their body position be and how is it likely to impact them and/or other climbers?

With route climbing, this means considering swing hazards, whether on top rope or lead, clipping positions, and the relative degree of difficulty lower in the climbing, where a climber could be likely to ground fall or take a hard swing into a belayer. With bouldering, falling is part of the activity, and usually, climbers may be failing more than succeeding, if pushing themselves. This means thinking about lateral movement and especially higher, dynamic moves, and the falls one can take. When placing holds around other existing problems, we also want to think through implications of a climber on one problem and potentially hitting another, in the act of falling. Or, if one problem has a dynamic jump on a vertical wall, moving dynamically upwards, we would want to be careful not to have large protruding shapes in that area that might obstruct the climber, in the act of climbing or falling.

With creating specific movements, routesetters also can be aware of common strains on the muscles or tendons that can create injury. Some gyms or routesetters will strictly limit the use of small pockets entirely, for example, as some believe pockets may be more likely to cause tendon or pulley issues. Anything that involves a proportionally high degree of strain on one particular area during a movement, are things both routesetters and climbers alike can take caution with. This could be something simple like pulling most of one’s body weight on a very small crimp, or it could be more full body movements – a hard drop-knee or a shoulder-press above the head.

The challenge for routesetters is that what climbers may do is really in their own hands, so we can only do our best to anticipate. Especially with respect to a climber’s own body and knowing when to push, where to pull, and how to stay cautious with movement that may create injury, every climber should be aware of their own limitations. Whether when setting to be explore creativity, to challenge a field with a specific level of climbing or style, or when considering safety, like difficult body positions or falls, as routesetters our awareness is about what’s likely for everyone we can imagine in the climbing situation. For the individual person, as in climbing in general, their focus also must be on their own body awareness. In the perfect world, we create interesting climbing movements, ask intriguing questions of climbers, and they try to solve them. If nobody gets hurt, climbers have fun, and people have a reasonably fair chance to succeed, then everybody wins! (well… except in competitions ; )

Chris Danielson in the zone. Photo Credit: Berti Willer

Below, check out the sponsors of Chris and give some support to eGrips, So iLL, Teknik, Trango, Flashed and Flathold

[ www.e-grips.com ] [ www.soillholds.com ] [ www.teknikhandholds.com ] [ www.trango.com ] [ www.flashed.com ] [ www.flathold.com ]

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

> Some gyms or routesetters will strictly limit the use of small pockets entirely, for example, as some believe pockets may be more likely to cause tendon or pulley issues.

I think this is situation dependent. It would be irresponsible for a gym in Bavaria (where I live) not to offer the opportunity to train on pockets. People are going to be going to the Frankenjura, and there’s technique to being safe on pockets – choice of finger combinations & stacking, direction of grip. Better to learn this in a controlled environment than try it for the first time on a runout route.

Hi Alan,

Great comment. I completely agree with both sides and that it is situation dependent. It is typically up to the individual routesetter and the gym management to determine hold selection. The decision may be based on proximity to similar outdoor terrain (such as pockets if close to Frankenjura or cracks if close to Yosemite), the percentage of membership that are indoor climbers versus outdoor climbers (to determine the need to mirror local crags), and the liability (at least here in the United States) that the gym is willing to accept.

[…] Full Interview: Route Setting to Prevent Injury with Chris Danielson […]