Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs)

Introduction

Every sport has its characteristic injuries. In climbing, finger and shoulder injuries are often the first that come to mind, among many others. But with the recent rise in popularity of rock climbing, more information is emerging regarding lesser known conditions that can plague climbers. Just in the past year, several professional sport climbers and experienced medical providers have been voicing serious concerns for the overall health of climbers.

In June 2023, professional climber Alannah Yip called out the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) for no longer screening athletes’ body mass index (BMI).

In July, Dr. Eugen Burtscher and Dr. Volker Schöffl resigned from the IFSC Medical Commission. Olympic gold medalist Janja Garnbret posed the question, “Do we want to raise the next generation of skeletons?” on her Instagram.

In August, German climber Alexander Megos posted a YouTube video with Dr. Schöffl titled, “Climbing Has A Problem.”

What do all of these events have in common? Something called Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, or REDs for short.

REDs is officially defined as, “a syndrome of impaired physiological and/or psychological functioning experienced by female and male athletes that is caused by exposure to problematic (prolonged and/or severe) [low energy availability]” (Mountjoy et al., 2023). In simple terms, it encompasses all the problems that can occur if an athlete is not getting enough nutrition to support the energy demands of their sport, everyday activities, and basic physiological functioning. This imbalance results in an energy deficit, or low energy availability (LEA).

LEA can occur in the short-term without causing any lasting side-effects, such as after a hard workout and before refueling. But if that energy deficit is big enough or prolonged enough, the result is REDs and the consequences are severe (Morgan et al., 2024; Mountjoy et al. 2023).

Signs and Symptoms

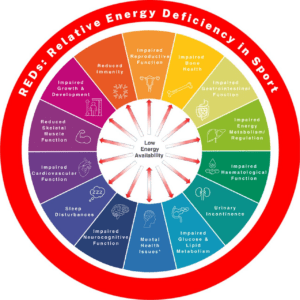

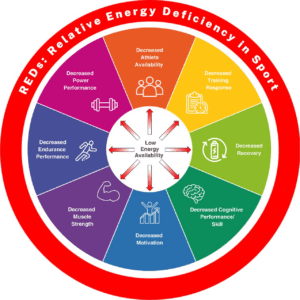

There are many paths that can lead to REDs. An athlete may be purposefully consuming less food in an attempt to improve performance, attain a certain weight or body type, or many other reasons. It may also be unintentional, simply by not knowing the proper amount and type of nutrients your body needs to function properly. Regardless of the reason, once the body does not have enough energy to comfortably perform all the tasks it is being asked to do, different biological systems begin to malfunction. As a result, the manifestations of REDs can be extremely varied, ranging from impaired metabolism to skeletal muscle dysfunction to cardiovascular complications. The links between problematic LEA and all of these biological systems has not been researched thoroughly and remains a proposed relationship, not proven yet. An exception is the link between LEA, reduced bone density, and menstrual function in women, which has been long called the female athlete triad. There exists an analogous condition, the male athlete triad, in which energy availability, bone density, and reproductive health are intertwined. There is strong evidence supporting the relationship between these three factors, but with the advent of REDs, it is clear that more research needs to be performed to explain the variety of symptoms observed in individuals with problematic LEA. One notable aspect of the current REDs system model is that mental health and LEA are reciprocally related. That is, problematic LEA can lead to mental health issues but the converse is also possible.

A huge reason why REDs is so concerning is because it can lead to chronic changes, affecting a person for decades after recovery. For example, decreased bone mineral density can lead to early onset osteopenia or osteoporosis, causing increased bone fractures. That is why prevention is the best solution, as discussed below (Morgan et al., 2024; Mountjoy et al., 2023).

(Mountjoy et al., 2023)

(Mountjoy et al., 2023)

Diagnosis & Treatment for REDs

There are many challenges to diagnosing REDs. The effects of low energy availability are not necessarily obvious or immediate, and a person does not need to have all of the signs and symptoms listed above for a diagnosis of REDs. The diagnosis is also not exclusive to high-level athletes. The amount of exercise or training is not the defining factor, rather the lack of energy availability to support the physiological demands of the sport.

Identification of low energy availability (LEA) is what confirms a REDs diagnosis. However, estimating energy availability is more complex than previously believed. Several methods exist, but the best way is to measure an individual’s fat-free body mass. The gold standard for this measurement is with a DXA scan, which is costly. Bioelectrical impedance using a portable device is less accurate but more convenient (Cabre et al., 2022). BMI has been used as a screening tool for REDs, notably for competition climbing, but this measure is largely inaccurate. BMI is a widely used estimation of body fat content based solely on height and weight. However this measurement is not universally accurate by any means. Muscle mass is more dense than fat, so a person who is very muscular with little fat may be classified as overweight according to BMI standards. Age, sex, ethnicity, and race also affect how accurately BMI can predict body composition. Even in the instances when BMI proves accurate, it alone is not enough to identify if an athlete is at risk for REDs. Someone with a normal body composition can still be experiencing energy deficits because poor nutrition does not necessarily result in weight loss. Conversely, a person who is underweight according to BMI standards may be fueling properly. The relationship between body weight, height, fat content, and energy availability is too complex to be accurately captured by one data point such as BMI.

Furthermore, in pre-teens and adolescents, any measure of body composition is strongly advised against unless absolutely necessary as it can drive body image issues and fixation on weight (Morgan et al., 2024).

For most clinicians, the best way to assess for REDs is by using the Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport Clinical Assessment Tool Version 2 (REDs-CAT 2) (Cabre et al, 2022; Heikura et al., 2023). This model was developed by the International Olympic Committee and breaks down the process into three steps: screening, risk assessment, and diagnosis/treatment.

Treatment for REDs is primarily spearheaded by a qualified nutritionist and physician with REDs experience in order to improve energy intake and address any medical complications. Depending on the case, a psychologist or other specialist practitioners may be needed in order to address the root causes of an athlete’s low energy availability. The research places emphasis on the need for a team approach to treating REDs, since so many different biological systems are affected. This team should include the athlete, caregiver, trainers, and coaches, as well as the relevant medical professionals.

REDs in Climbers

The available research on REDs, which has mostly been conducted on runners, rowers, and cyclists, supports that endurance athletes are at higher risk (Cabre et al., 2022). Climbers are no exception. Although some climbing styles such as bouldering and speed are less innately endurance-based than others, the energy demand is still high. You might spend less than a minute climbing continuously, but if you hiked an hour to get there, or biked to the gym, and made many attempts, that all adds up to a substantial energy output. This is not a problem by itself. Issues arise when the body’s energy supply is not replenished enough through food and drink to support normal physiological functions, recovery, and then more training and climbing.

In addition to the physiological demands of climbing, there are less quantifiable factors contributing to an increased risk of REDs. One of these is the stereotype that climbers need to have a lean, muscular build to perform well. The perpetuation of this “ideal” body type adds pressure to drop weight, leading to reduced nutritional intake, and ultimately a severe energy deficit. In reality, a healthy body is the one that will perform the best. And that looks different for everyone.

In competition climbing, weigh-ins and BMI measurements are sometimes used as a screening tool to help identify climbers at risk for REDs or other health concerns. While these screens are a step in the right direction, there are several problems with this approach: the expectation of weight measurements can cause an athlete to hyperfixate on weight as a performance indicator; BMI is an imperfect measurement (discussed in Diagnosis & Treatment); and many climbers in the adult competition circuit are minors and should not be subjected to body composition measures due to the risk of causing body image issues (Morgan et al., 2024).

Where Does Physical Therapy Come In?

While direct treatment for REDs does not fall within the scope of practice of physical therapists, there is still a place for PTs in helping to manage this condition. Physical therapists are among the few healthcare professionals who see their patients regularly, for extended treatment sessions, over relatively long periods of time. This makes them optimally placed to monitor for and recognize signs and symptoms of REDs. Identification of athletes at risk for or already experiencing REDs is crucial to minimize the short and long-term health repercussions of this condition. Physical therapists should be ready to refer to a nutritionist and experienced physician if noticing any concerning indications of low energy availability or REDs in a patient. Even one sign or symptom of REDs is enough to warrant further investigation.

It is also important for physical therapists to understand the implications of REDs on their treatment. If an athlete has been diagnosed with REDs, they are almost certainly going to present with secondary limitations that affect their performance and response to treatment. For example, fatigue, frequent injuries, and bone and muscle breakdown are among the many manifestations of REDs. Performing a detailed subjective history and thorough clinical exam covering all systems is crucial to develop the best treatment plan for these individuals. Educating the athlete, and their family/coaches as appropriate, is key to ensuring optimal recovery and improved function.

Finally, since prevention is the best medicine, PTs can join other clinicians, coaches, and athletes themselves in raising awareness about REDs. The more people who are aware of the condition, how it presents, and how it is treated, the better we can ensure that athletes of all ages and all levels can maximize their performance and continue to enjoy their sports.

The Research

- British Journal of Sports Medicine. (2018). 2018 update: Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). British Journal of Sports Medicine Blog. https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2018/05/30/2018-update-relative-energy-deficiency-in-sport-red-s/?utm_content=link6&utm_campaign=articles_id_0&utm_medium=articles_post&utm_source=ukclimbing

- Cabre, H. E., Moore, S. R., Smith-Ryan, A. E., & Hackney, A. C. (2022). Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Scientific, clinical, and practical implications for the female athlete. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Sportmedizin, 73(7), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.5960/dzsm.2022.546

- Grønhaug, G., Joubert, L. M., Saeterbakken, A. H., Drum, S. N., & Nelson, M. C. (2023). Top of the podium, at what cost? injuries in female international elite climbers. Frontiers in sports and active living, 5, 1121831. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1121831

- USA Climbing. (2023). USA Climbing protocol for health screening and underweight athletes 2023. https://usaclimbing.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/USA-Climbing-Protocol-for-Health-Screening-and-Underwieight-Athletes-2023_23032345.pdf

- Heikura, I. A., Mountjoy, M. L., Ackerman, K. E., Bailey, D. M., Burke, L. M., Constantini, N., Hackney, A. C., McCluskey, P., Melin, A. K., Pensgaard, A. M., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Torstveit, M. K., Jacobsen, A. U., Verhagen, E., Budgett, R., Engebretsen, L., Erdener, U., & Stellingwerff, T. (2023). International olympic committee relative energy deficiency in sport clinical assessment tool 2 (IOC REDs CAT2), British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(17). https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-107549

- Heikura, I. A., Uusitalo, A. L., Stellingwerff, T., Bergland, D., Mero, A. A., & Burke, L. M. (2018). Low energy availability is difficult to assess but outcomes have large impact on bone injury rates in elite distance athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), 403-411. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0313

- Joubert, L., Warme, A., Larson, A., Grønhaug, G., Michael, M., Schöffl, V., Burtscher, E., & Meyer, N. (2022). Prevalence of amenorrhea in elite female competitive climbers. Frontiers in sports and active living, 4, 895588. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.895588

- Keay, N. (2019). Returning to sport/dance restoring energy availability in RED-S? British Journal of Sports Medicine Blog. https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2019/03/26/returning-to-sport-dance-restoring-energy-availability-in-red-s/?int_source=trendmd&int_medium=cpc&int_campaign=usage-042019

- Morgan, C., Schumann, T. L., Hoogenboom, B. J. (2024, Feb 17). Across the Spectrum – the Triad and Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome [Conference session]. APTA Combined Sections Meeting, Boston, MA, United States.

- Mountjoy, M., Ackerman, K. E., Bailey, D. M., Burke, L. M., Constantini, N., Hackney, A. C., Heikura, I. A., Melin, A., Pensgaard, A. M., Stellingwerff, T., Sundgot-Borgen, J. K., Torstveit, M. K., Jacobsen, A. U., Verhagen, E., Budgett, R., Engebretsen, L. & Erdener, U. (2023). International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(17): 1073-1097. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994

Author Bio

Emma-Leigh Lamonde is a Doctor of Physical Therapy student at the University of Rhode Island. In addition to her academic pursuits, she is an avid climber, runner, and hiker. She can be contacted at eklamonde@gmail.com.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.