Posterior Chain Climbing

You’re out at the crag with beautiful crisp temps. You just finished a training cycle and your core is rock solid. You calmly wait while every team-kid warms up on your project. When the coast is clear you get situated on the sit start, take a deep breath and….. you can’t pull off the ground. Some time passes and you begin working the upper sequence. It looks promising, but every other move your feet cut and you cannot seem to keep tension through your reaches. What does this mean? You have been training for months, What’s missing?

I am sure that many climbers have had a similar situation whether in the gym or outside. Even advanced climbers can run into these issues, and often they will mask them under other strengths. What element is missing? The posterior chain!

What is the posterior chain (PC)? It is the evil twin of our anterior chain ( the muscles that pull us into a ball). So, think of everything along the back of your body (lats, shoulder external rotators, glutes, hamstrings, erector spinae, and multifidus). Each of these muscles act in opposition or co-contraction to the muscles in our anterior chain, especially during compound movements.

Okay, but why should you care? Three reasons: injury prevention, a balanced core, and increased performance.

With increased input from the posterior chain we can improve our abilities on steep terrain, better use heel hooks and extended body positions and reduce our risk of injury. Sounds too good to be true, but hopefully by the end of this article you will see why you cannot send without the posterior chain.

Why the Posterior Chain Matters:

- Injury prevention: The best climbers in the world have one thing in common; they avoid getting injured. The benefits of a full season injury free far outweigh those gained by training close to failure every session. With each movement in climbing our pulling muscles must be balanced by their antagonists (think of two teams playing tug of war). This allows for smooth coordinated movement across joints and the retention of tension throughout the body. In key joints such as the shoulders and hips the PC is essential to proper function.

- Many of the muscles of the PC are used regularly in climbing (lats, traps, and rhomboids); however, how they fire is equally as important as their engagement. Keeping your muscles firing in a coordinated sequence reduces chance of overuse in smaller muscle groups and improves fluidity of movement.

- If the PC is trained properly, motor patterns are built and reinforced. This allows for coordinated firing during taxing movements on the wall.

- Balanced Core: I would wager that the average climber thinks of their core as the six pack (Rectus Abdomonis), the obliques (Internal and External) and maybe in the anotomically minded–the (Transverus Abdominis). But this ignores large pieces of our trunk, mainly the PC. Our key core muscles of the PC are the Erector Spinae, Multifidus,and Quadratus Lumborum.If you think of your trunk as an unopened soda can, when all muscles are properly engaged it is rigid and hard to deform. If your PC isn’t engaged, it is like cracking the tab; the pressure and stability are lost. When you only contract your anterior core you are leaving your spinal column unsupported and giving your anterior core extra work that the PC is designed to do. Think of the climbers you have seen who seem to float in a position after their feet cut. In this situation they are perfectly coupling their PC and anterior core to provide a stiff tube (our trunk) off of which their arms and legs can then act.

- Example: When standing up into a undercling or deadpoint reach coordinated core contraction makes holding these high tension moves significantly easier.

- Increased performance: It goes without saying that reducing injury and balancing your core will improve performance, but we can go even further. Proper training of the PC will improve your ability to toe in on overhanging terrain, strengthen heel hooks and increase cross body tension.

- Many climbers associate footwork on steep terrain with hip flexors, but they serve more to advance your legs upward or place them back on the wall. In order to keep your toes on a hold, the correct amount of pressure must be applied. If you are on an overhang this will require you to pull down and back with your legs activating your glutes, hamstrings and gastrocnemius which, as you can guess, are part of your PC.

- You simply cannot perform a heel hook without activating your PC. But if you want to use your leg as a third arm like Brooke Raboutou, you will need to use the PC to its full potential. This means externally rotating the hip, pulling in with the hamstrings and transferring this motion through your erectors into your trunk. I do not think the advantages of a well used heel hook need be explained.

- When we get into situations where our only points of contact are opposite each other (say, only a right toe moving to a left hand) often we blame lack of finger strength, but coordination of the PC could be the culprit. When pressing through a foot we must transfer this force through the chain to allow us to unweight our hands thus reaching the next hold. By activating the PC prior to the crux movement we take as much weight onto our stable foot as possible and allow our upper extremity to move off a stable surface rather than one that is slowly falling away from the hold. Now this situation also has to do with motor control not just strength, but that will be covered later on.

Disclosure Statement

The information provided here is for educational purposes and is not medical advice. Please schedule an appointment with a licensed physical therapist or your primary care physician for more guidance and specific recommendations.

Posterior Chain Assessment

The posterior chain is too large and complex to give a one-size fits all assessment of its effect on anyone’s climbing. However we can make inferences from climbing performance and follow them up with more specific tests.Do you?

- Struggle to keep your feet on during overhung climbing

- Struggle with sit starts

- Struggle to keep body tension during long reaches or standing into underclings

- Fall out of heel hooks often

If you answered yes to one or more, it may be worth your time to investigate your posterior chain. Try these five assessment tools and record yourself so that you can see any changes in your form. Note that form is crucial for both safety and performance. Simply completing the movement is not enough. You must engage the proper muscle groups without compensation. If you do compensate, this is a good indication that this area may need attention. This may be a good time to consider coaching or having a friend watch you for outside feedback.

- Traditional deadlift

- Starting with body weight and progressively adding weight, knees fully extended, flat back, no twisting in torso

- Disclaimer : if you do not feel confident in your form or are new to this exercise sart with a 10 rep max to calculate your 1RM and increase weight slowly

- Kettle bell deadlift

- The same as the traditional lift with the barbell, except you use a kettle bell

- Plank with Elevated feet and Side plank with elevated feet

- Looking for early butt rise, knees bending, hip drop, or under 60 sec

- Ring Rows with elevated heels

- Looking for folding at hips, rounding/ falling out of scapular retraction

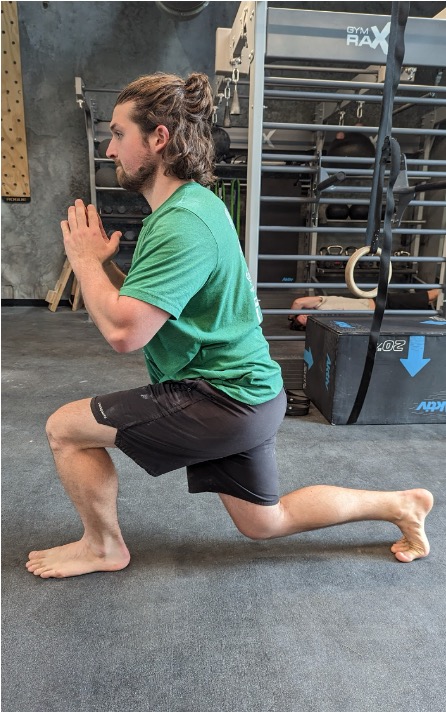

- Lunges along a line, foot in line with heel

- Looking for loss of balance, trouble coming out of squat

- Superman holds

- Looking for less than 30 seconds, uneven shoulders, shrugging

If any of these exercises felt overly difficult or couldn’t be completed with proper form, posterior chain training in the next section could benefit your climbing.

Interventions

There are many exercises online on how to improve your posterior chain, as these are popular muscles for aesthetically driven athletes. I will list some simple ones by muscle group below; however, better results will be gained using sport-specific exercises. For instance, a deadlift is one of the best ways to isolate the glutes for strength, but we rarely use just our glutes for an extension movement in climbing. We use the glutes in conjunction with our PC to maintain tension throughout our body. Therefore, exercises such as ring rows with elevated feet can help to train strength while improving motor control throughout the whole posterior chain.

Isolation exercises

- Deadlifts

- RDLs

- Hamstring curls

- Hip ABD with a band AKA clam shells

- Hip ADD with ball between knees/ or at Adductor machine

- Lower trap pulls with band

- ER of shoulder with bands

Compound exercises

- Ring rows (RR) with elevated feet

- RR with 1 foot on

- Reverse plank on swiss ball

- Reverse plank with knee flexion and extension

- TRX Ys and Ts

- Vary feet for increased lower extremity involvement

- Front plank with elevated feet

- Side plank with elevated feet

- Hip drops and raises

- Dead bugs with ball or climbing pad for compression

- Hip and shoulder mobility drills if mobility is a limiting factor

About the Author

Colin Ramsey is a 2nd year DPT student at Western Carolina University in Asheville, NC. Colin enjoys climbing with his partner and dog in the Appalachian mountains as well as traveling to sport climbing destinations out west. You can contact him at ramseypcolin@gmail.com

Research

- Cowell, Kevin. “Climbing-Specific Body Tension.” The Climbing Doctor, 20 Nov. 2022, https://theclimbingdoctor.com/climbing-specific-body-tension-2/.

- De Ridder, Eline MD, et al. “Posterior Muscle Chain Activity during Various Extension Exercises: An Observational Study – BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders.” BioMed Central, BioMed Central, 9 July 2013, https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-14-204.

- Santello G, Rossi DM, Martins J, Libardoni T de C, de Oliveira AS. Effects on shoulder pain and disability of teaching patients with shoulder pain a home-based exercise program: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(10):1245-1255.

- Bier JD, Scholten-Peeters WGM, Staal JB, et al. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Phys Ther. 2018;98(3):162-171.

- Roseborrough A, Lebec M. Differences in static scapular position between rock climbers and a non-rock climber population. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007;2(1):44-50.

- Huxel Bliven KC, Anderson BE. Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports Health. 2013;5(6):514-522. doi:10.1177/1941738113481200

- Ronai, P. (2015). The bunkie test. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 37(3), 89-92.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.