Optimal Training and Injury Prevention Techniques for Climbers with a Full-time Schedule

By Andrew McClure PT, DPT

We all wish we could climb as much and as hard as the pros. However, most of us have to maintain a full-time schedule with jobs, family, school, and the other challenges of life. It can be tough to stay in shape, let alone see improvements. Knowing optimal strategies for training is important for a busy schedule. So, what are the principles of training for those of us with limited time to climb and train?

In addition, nothing brings our climbing progress to a halt faster than injuries. Some injuries are the result of “bad luck”, like a fall, and are harder to foresee and avoid. Many climbing injuries are due to the stressful and repetitive nature of climbing and are more avoidable. Rest, correcting poor posture or positioning, and building greater strength and resilience can go a long way to staying injury free and being able to train for continued progress in climbing. In addition to training, keeping your body well rested and properly fueled will help to be ready to train hard to get the most out of each session and should be considered a prerequisite for any climbing or training session.

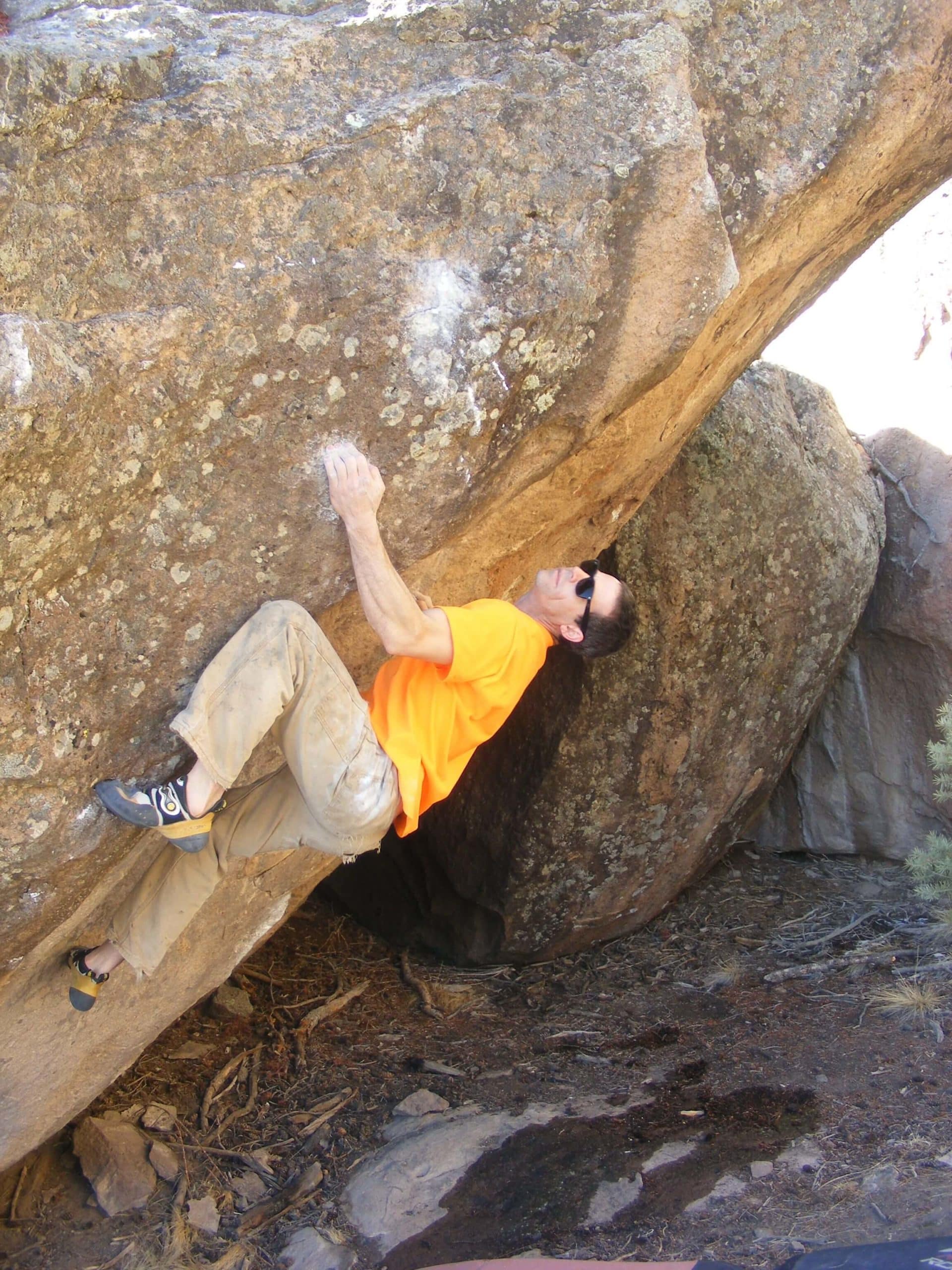

Andy O'Brien on Sinn Fein 5.12c

Rest/Recovery

It’s important to remember that rest days are more than just days that we aren’t climbing. Recovery is probably a better term to use than rest as the real goal is to fully recover between training or climbing sessions. Recovery is the time needed to rebuild the tissues damaged during training that lead to adaptation and improved strength of muscles and tendons. Recovery should be more of an active process than a passive waiting game. Of course, it is important to rest and not over exert one’s self with strenuous activities like yard or trail work, or cleaning and bolting a new route. With a full-time schedule it is important to keep up with responsibilities, just know that some of these activities won’t aid in recovering to climb or train at your maximal potential.

Recovery starts before chalking up. Here are some great tips from training master Steve Bechtel.

- Before climbing or training, pre-game “with around 30-50 calories in the form of a small snack or protein drink” to aid recovery even before starting, or during, your climbing or training session.

- Afterwards, consuming a healthy snack or meal with non-sugary carbs and protein within a couple hours provides your body with the macronutrients it needs to build and repair tissues affected by training. Bechtel sums it up as “simply to eat within a couple of hours after a session, and to make sure that you have a full serving of protein at that time. … a sandwich, a salad with steak or chicken, or even an omelet would be fine, too. Aim for 150-250 calories.”

- Drinking water before and during activities is shown to reduce injury, maintain our body’s proper fluid volume and buffer against thermal stress. Bechtel notes that “being under-hydrated can prolong soreness and extend recovery times.” We all wish beer counted as water, but alcohol slows recovery. Consider drinking 20 oz of water in place of a beer and avoid binge drinking except on special occasions.

- Use activity to speed recovery. Although intense activity can slow recovery, a minimum of 30min of light aerobic activity daily helps promote circulation to provide nutrients to recovering tissues and remove waste. Steve recommends that “You should keep your heart rate below 60% of your maximum at all times, and most of your time should be spent well below even this mark.” Think of this as a chance to keep moving and speed recovery, not another form of training.

Diet

Optimizing one’s diet is very specific to each person and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. If you are looking for more personalized or specific information, find a dietician or nutritionist to help. Tracking what you eat with an app like MyFitnessPal can help understand where you’re at, as far as calories and macronutrients, with your current eating habits as well. Here are some basic pointers to optimize energy for climbing and training.

First off, try to eat 3 meals a day that contain a similar amount of calories and macronutrients. This will help you keep your blood sugar more stable to avoid the spikes and drops that cause us to look for quick snacks that are usually filled with sugary carbs. This also helps keep our bodies fueled to be ready to climb or train. In addition to 3 even and balanced meals, make sure to add a hearty snack within an hour of beginning a training session. A healthy diet will provide the vast majority of climbers the micronutrients (vitamins/minerals) they need, just in case you wondered.

Finding the right balance of macronutrients can be key to feeling energized and ready to train or climb. Nutritionist Neely Quinn of TrainingBeta recommends aiming for macronutrients in these amounts based on an 1800 calorie diet:

- Protein – Neely states that it is rare for her clients to be consuming enough protein when she assesses their diet at the beginning of her time working with them. Climbers should aim to get ~25% of their calories from protein, or ~112g for 1800cal diet.

- Carbohydrates – should account for ~40% or 180g with most of that in the form of starchy carbs from foods like potatoes, grain, beans, and starchy veggies (as opposed to leafy and “green” veggies which are low in carbs and high in micronutrients). Starchy carbs are processed more slowly which prevents the sharp spikes and dips in blood glucose caused by sugars. Try to limit sugary carbs to <40g which can be tough when a single cup of yogurt contains ~19g of sugars.

- Fats – Neely notes that these seem to be less of a problem to balance out your diet and typically account for ~30-35% of macronutrients.

On crag days, keep in mind the following points:

- Bring foods that you have found that make you feel good and energized.

- Eat a meal you know makes you feel good, at the normal time you would normally eat a meal on any other day.

- Eat simple sugar! When climbing our body demands more glucose and this is the time basic sugars are great for snacks before climbs or between meals.

- But remember fruit sugars (fructose) are processed by the liver and stored as glycogen which takes longer to provide energy to our bodies. On climbing days it makes sense to snack on cookies or pastries which quickly raise blood glucose and provide quick energy.

The Author on Dreamsnatcher at Lincoln Lake

Sleep

Studies, including one by Knowles et al., have shown that a lack of sleep can limit maximal strength, disrupt hormone balance and reduce motivation. Although losing sleep for just one night is not shown to decrease performance, consistently getting inadequate sleep can limit performance. The time we are asleep is a key to recovering from training or climbing and not to mention our general physical and mental health. Stack the deck in your favor and prioritize quality sleep to improve your ability to recover faster and therefore train harder.

Luckily training and exercise is one of the keys to getting optimal sleep. Avoiding caffeine, nicotine, and eating heavy meals close to bedtime will also help you get a better night of sleep. Alcohol is also known to disrupt sleep and even reduce the production of Human Growth Hormone which is an important hormone for cell reproduction that helps the body heal, improve cognition, and build muscle and bone. Keeping a standard sleep schedule and a quiet, dark, and cool environment to sleep in are also key to improving sleep quantity and duration. Stress and worrying is a common detractor to getting to sleep and staying asleep. Try to keep your mind free at bedtime and deal with stress before you head to the bedroom. Last, blue light from TV, indoor lighting, and phones or computers can disrupt our circadian rhythm. Turning off bright lights or running apps that block blue light before bed are beneficial, however adequate exposure to bright light (preferably sunlight) during the daytime is important to signaling our bodies that it is time to be awake.

Have a Plan

Every plan should start with the end result in mind. If you are starting a training plan, what is the goal you hope to achieve? Knowing where you hope to finish allows for mapping out the steps to get there. Pick one goal for this training cycle, be it finger strength, pull ups or flexibility, and focus on that. Attempting to achieve too many goals at one time will likely lead to poor results for each of those many goals. Stay focused and make gains in one area at a time. When training with a busy schedule, this amount of focus is the best path to success.

When planning your training cycle, design the duration off of the number of training sessions, not a specific time period. We all progress and recover at our own pace. Planning your training cycle in this manner helps adjust for a busy schedule. Attempting to pack training sessions into a busy schedule can lead to training when you have not fully recovered or sacrificing valuable climbing days. Completing 8-12 quality training sessions should show measurable results towards achieving your focused goal.

Finger Strength

Finger strength is the single measure that is likely to determine a climber’s ability. It can be arduous to dig through all the protocols and different recommendations to build finger strength. Hangboarding is the gold standard to increase finger strength. Many commercially made boards are available and homemade versions have been used for decades. This specific and functional training method can be utilized by beginning or advanced climbers alike, but beginning climbers should stick to large holds to allow tissues like tendons and annular pulleys to adapt to the increased loads before attempting to hang from smaller holds. Hangboarding is typically done in a half-crimp position to actively engage the finger flexor muscles of the forearm and the intrinsic muscles of the hand, however an open-handed grip is commonly used when hanging from pockets or other holds that do not fit all four fingers. Training specific grips like a pinch grip or crimp grip also should be considered.

Hangboard training is intense and Eric Horst recommends that all climbers should always follow these rules to avoid injury:

- Perform a full body warm up before hangboarding.

- Avoid holds that are painful.

- Hang with good form with shoulder blades engaged and slightly bent elbows.

- Don’t overdo it! Do a maximum of two hangboard workouts a week and end your workout immediately if you feel pain in your finger joints, tendons, or pulleys.

Many protocols exist but the three most common are minimum edge, maximum weight, and repeaters. Thinking about the crux section(s) of a route or boulder, a climber must engage smaller and/or more sloping holds for a few seconds and repeat this for a few (or many) hard moves. All three of these protocols account for dealing with these difficulties, but what’s best? Training on a minimum edge size can be difficult and painful as holds get smaller and smaller. This style has its value but progress eventually becomes limited. The other two protocols will be examined in greater depth. A recent study by Lopez and Gonzalez-Badillo (2019) found significant increases in grip endurance with training regimens that consisted of either maximum weighted hangs or repeaters.

- Maximum Added Weight increases the load on a climber’s fingers while staying on a hold size that is still comfortable. This could be thought of as making the hold smaller relative to the amount of load the fingers must hold. Training with maximum weight avoids the issue of training on smaller holds and is typically done on a hold that is the depth of the distal phalange using a weight that a climber can hang from for about 10 seconds. If a climber is unable to hang from a hold of this size it would be best to continue using larger holds or employing a counterweight system (a way to decrease the load on a climber’s fingers by connecting a weight to the climber with a rope going over a pulley to effectively make the climber weigh less) to build up to this. The actual hang will last 7 sec and followed by 1 minute of rest and repeat 3 times for one set. Complete 2-6 sets depending on your current level of fitness.

- Repeaters are a good match to how climbing is performed, short hangs followed by a shorter rest done repeatedly. Find a hold that you can complete the full set of repeaters on, but will be somewhat difficult to complete the last couple hangs in a set. A typical program consists of a 7 sec hang followed by 3 sec of rest done 6 times in a row, this is one set. Take a 1-minute break and perform a total of 5 sets. After the fifth set take a longer break of 10-15 min and perform another 5 sets.

Training specific grips used in climbing should also be discussed. Pinch Training is also a valuable tool to develop greater opposition strength of the thumb. Pinch blocks can be purchased, or are easy to make, to train a pinch grip. Pinches come in many sizes so it is important to train different widths of a pinch grip, but always make sure to use only the distal portion of your thumb to train.

It has long been thought that training in the full crimp position is a big no no, but finger strength guru and Beastmaker creator, Ned Feehally disagrees. “In my opinion, it’s really important to train the full crimp grip position because a lot of hard moves on rock revolve around crimping really hard on small holds.”, Feehally says. Adapting our fingers to this position makes them stronger, develops the intrinsic muscles of the hand, and will minimize the risk of injury. Feehally recommends getting comfortable with the crimp position while crimping the edge of say, a table, and advancing to standing on the ground and loading a crimped grip on a hangboard before finally moving to hanging from a crimp grip. As always, make sure your body and fingers are warmed up before crimping on a hangboard. Training finger strength is one of the best and most specific forms of training a climber can do.

Shoulder Strength and Stability

Shoulder strength and stability is an important factor contributing to finger and grip strength. Like the foundation of a house, what are strong walls without a stable base for them to sit on? Take the one-armed pull-up. It is much less difficult to hang from a pull-up bar with one hand than to engage your shoulder to actually start to pull up. Of the muscles that attach to the scapula, some work to stabilize the scapula on the torso and some work to move and stabilize the humerus as it moves the arm through space to grab and then pull on a hold. Both of these functions are vital to strength and mobility.

Scapular stability is the strong foundation which enables a climber to pull on a hold and actually create movement. It is important to engage the muscles that stabilize the scapula and maintain proper scapulohumeral rhythm during overhead movements of climbing to have a strong foundation and prevent injuries. Some of the key muscles to target are lower trapezius and serratus anterior which depress or hold down the scapulas. Y’s, scapular pull-ins and shoulder shrug dips will build lower trap strength while a serratus punch or push-up plus develop serratus anterior strength and control. T’s and rows build middle trap and rhomboid strength to keep the scapula retracted or from pulling out and away from the spine. In addition to strength, maintaining proper scapular motion when reaching overhead prevents impingement injuries. Ideally, after the initial movement of the humerus, the scapula will rotate upwards one degree for every two degrees of motion the humerus makes. This upward rotation is also provided by the lower trap and serratus anterior which we already discussed strategies to strengthen. Good hanging posture involves engaged scapulae that can move in harmony with the humerus, creating a stable foundation while providing the proper coordination and mobility to prevent injuries.

We have all heard of the rotator cuff, but few people actually know what this even refers to. It is a collection of muscles that are attached to the scapula and wrap around the head of the humerus to provide stability to hold the humerus into the glenoid fossa or shoulder socket. These muscles raise, lower, and rotate the humerus in the glenoid fossa but above all provide stability. They not only hold the humerus securely in the glenoid but also keep it from rising up and banging into the acromion process (that pointy bone on the top of the shoulder) as the arm reaches overhead. It consists of the subscapularis, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and teres major muscles (teres minor is also included by some experts).

A couple of key points to consider are, first, that the supraspinatus tendon runs right under the acromion process and is commonly subjected to being pinched or impinged during overhead motions. When the other muscles of the rotator cuff are weak, they are unable to pull the humerus downward during overhead motions, and keep the humeral head from rising up and banging into the acromion with the supraspinatus tendon trapped in between. Second is the importance of external rotation. Think of the chicken wing, when a climber is getting tired on a route and their elbows start to stick out and everything begins to go wrong. Before long they are hanging on the end of the rope. This occurs because the external rotator muscles have become too fatigued and the climber is unable to maintain their engagement and keep their center of mass near the wall. All of a sudden, their elbows are sticking out away from the wall, and instead of pulling down on a hold they are now pulling outwards, and “pop”, they slip right off the hold. Of the rotator cuffs muscles mentioned above, only the infraspinatus and teres minor provide external rotation. It is important to strengthen these muscles by performing external rotations in functional positions for climbing with the arm at or above shoulder level. Other exercises to add to the shoulder strength quiver are overhead press, bench press, and deadlifts that develop the rotator cuff muscle’s ability to stabilize the glenohumeral joint. The shoulder provides proximal stability to enable strong fingers to maintain a secure grip on even the smallest hand holds. Climbing requires all links of the kinetic chain to be strong, from the fingertips to the toes.

The author tests his reach and his shoulders on The Fire From Within

Core Stability

A strong core links the fingertips to the toes so a climber can transfer power in between these two points of contact. Remember all those sit-ups from gym class, I’ve got good news, throw those out the window! The core provides a stable base for our limbs to move on and is not designed to create movement. Training by superimposing movement to challenge the core to maintain stability is key. The core muscles include the abdominals as well as the back and acts like a corset to tighten and provide support. If one area of the core is weak, then there can’t be true stability. Some go-to exercises include L-hangs, ab-rollouts, windshield wipers, a front lever, and even a low bar back squat. These exercises can be modified by shortening the lever arm (i.e. tucking your knees for L-hangs or front levers) or moving through a smaller range of motion (wipers and rollouts) to build up to performing the exercise at full difficulty. The low bar back squat is an excellent core exercise for supporting extra weight and then moving while maintaining control of the core throughout. The muscles of the low back are vital to include as well being the core muscles need to work as a unit. Exercises like supermans do a good job of activating the core muscles of the low back, and the dumbbell snatch is a great functional exercise for quickly engaging the core as well as the entire posterior chain.

The author keeping his core extra tight in Joe's Valley

Lower Body/ Power training

The lower body has the strongest, most powerful muscles in the human body. It is foolish not to train these muscles to work in your favor. Our legs push us up a climb, help pull our hips into the wall, and off-load our fingers by transferring our weight onto our toes or heels. If you don’t believe how important our legs are, think about how long you could stand on your feet, and how long you could hang from your arms? The difference is immense! Here are three main areas to target: calves for standing on small footholds, quads for pushing off of your feet, and glutes and hamstrings for pulling with your legs and keeping your hips into the wall.

- Calves – Calf raises are the standard calf strengthening exercise, but the goal should be to perform single leg calf raises with added weight. It is important to also perform it with a bent knee to strengthen the soleus, flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus muscles which are the primary muscles responsible for maintaining pressure on a foot hold when the knee is bent. Train using bent-knee calf raises in a standing or squatting (catcher’s) position.

- Quads – Quads are the power house of explosive movements including high steeping, deadpoint and dynamic movements. Although these are very strong muscles, it doesn’t mean a climber has the strength they need to make these powerful moves in crunched up positions. It is important to train these movements how they are often performed in climbing, with the hip and knee near the extreme end of flexion. Exercises like pistol squats help a climber develop strength and control in a functional way by relying on one leg. Squats are a standard for developing quad strength and also work much more of the body. The low bar back squat can count for training legs as well as core.

- Hamstrings/Glutes – Strengthening the posterior chain is crucial for heel hooking and keeping the hips into the wall especially as climbs get steeper. Heel hooking is very intense and can cause injury to an unprepared hamstring. Exercises like physioball hamstring curls (build up to single leg), deadlifts, and glute-hamstring curls (more advanced) will build these muscles. Glutes are also a compliment to the quads in that they extend the hips while the quads extend the knees allowing a climber to fully straighten their legs and achieve maximal reach to grab the next hold. Some exercises are the same as for hamstrings (deadlift) but in addition perform step-ups, barbell hip thrusts, low bar back squats, lunges, and single leg or split squats.

Antagonist Strength for Injury Prevention

It is important to have a good balance of strength throughout the whole body to prevent injuries. Think of a post sticking out of the ground, if it is pushed only from one side, it will fall over soon enough. But if two equal forces push against it from opposite directions, the post is perfectly balanced and should never fail. Climbing revolves around pulling down and outwards on holds so we need to put some time into training the opposite motions of pushing and pressing to keep our bodies balanced and injury free. Although many of the exercises listed above provide antagonist strengthening, here are some to incorporate into training sessions for the most commonly injured areas in climbers:

- Wrists – dumbbell wrist extension, pinch blocks, and finger extension against a rubber band or flat exercise band.

- Elbows – target the triceps (pushups or tricep extensions) and pronation/supination (hammer rotations).

- Shoulders – pike pushup and upright row to cactus position are a couple favorites incorporating pushing/pressing as well as external rotation.

- Bonus – Farmer’s carry (core and pulling up instead of down) and door/corner pectoralis stretch to open the chest and avoid the troglodyte look of rounded shoulders.

- Hip flexibility – it is built on strength to move into end ranges of motion as well flexibility. For a routine that focuses on building strength for flexibility check out this article and video https://www.trainingbeta.com/hip-mobility-for-rock-climbers/.

You Can’t Replace Climbing

Climbing technique will go farther than any amount of strength. We’ve all seen the newbie climbers from the weight room with more muscle than we can imagine, yet they are completely pumped and fall off a 5.9 jug ladder, halfway up the wall. Being a good climber is what the real goal is. There are numerous ways to use climbing as a training tool. Practicing climbs in the gym with drills like silent feet, sloth, and hover drills helps you use climbing to build specific strength. Steve Bechtel recommends using gym boulder problems to build endurance and power endurance and skipping route climbing all together with specific circuits. See his recommendations for bouldering circuits here: https://www.climbstrong.com/education-center/sessions-any-gym/.

At the crag or boulders give yourself every advantage rather than just throwing yourself at a climb over and over. Climbing with others who are better than yourself is a huge advantage even if it can be hard on your ego to watch someone float up your project as a warm-up. Work on beta on and and off the climb. Analyze beta on the route, look for footholds as a guide more so than hand holds, and critique your own technique while on a route. Could you turn your hip in to make that hand hold more positive? Then, rehearse and analyze beta at home. Once you can visualize every hand and foot movement at home, you only require the fitness to send the route. Watch others climb on your projects to gain new ideas and learn new tricks. Most climbers love to discuss beta so don’t be too shy to ask how they do a move or settle into a rest. Figuring out rests is often the difference between success and failure when a route is at your limit. Spend time learning the beta for rests just as you would for learning how to make the moves, and spend a similar amount of time and focus. Climbing is the true goal, so don’t miss an opportunity to get outside, just to get another session on a board.

There has been a lot of information and ideas laid out in this article. There are entire books written on each of these subjects. Hopefully this gives a solid basis for how to focus on improving your climbing ability with pointers for on and off the rock. To prevent injuries, climbers need to be strong throughout their whole bodies as well as being well rested and fueled. To be a great climber it takes a lot of time and dedication to master rock craft, but this includes what you can do at home by always working towards being the best climber you can be. A full-time schedule is just a time constraint that even many of the best climbers have had while working to be at an elite level. We are all created to do great things in climbing, it’s the everyday choices that separate the Joes from the Pros! Remember these key points:

- Use every opportunity to become a better climber and prevent injuries by incorporating small improvements in all aspects of your life like diet, sleep, proper rest, and planning/goal setting.

- Finger strength is the key factor in climbing and will produce the greatest payoff for your time.

- Shoulder strength and stability is the second most important aspect to put your focus in training.

- Strength is injury prevention, so work to be strong throughout your whole body including antagonist (push/press) muscles, legs, and core, in addition to your fingers and shoulders.

- Go climb! Outdoor climbing is the reason we train and can teach us so much. Get out there with climbers better than yourself and squeeze the value out of every opportunity you have to improve your technique, beta, and strategy, to be the best you can be and send your project!

Morgan Barnes loves to climb real rock!

References:

1. Recovery Training | Climb Strong. Published December 8, 2017. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.climbstrong.com/education-center/recovery-training/

2. Quinn, N., 2020. Unstoppable Energy Challenge.

3. Knowles OE, Drinkwater EJ, Urwin CS, Lamon S, Aisbett B. Inadequate sleep and muscle strength: Implications for resistance training. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2018;21(9):959-968. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.01.012

4. Hörst E. Training Finger Strength with a Hangboard. Training For Climbing – by Eric Hörst. Published August 30, 2020. Accessed March 6, 2022. https://trainingforclimbing.com/video-training-finger-strength-epic-tv-episode-1/

5. López-Rivera E, González-Badillo JJ. Comparison of the Effects of Three Hangboard Strength and Endurance Training Programs on Grip Endurance in Sport Climbers. J Hum Kinet. 2019;66:183-195. doi:10.2478/hukin-2018-0057

6. Should You Train Full Crimped? Climbing. Published January 31, 2022. Accessed February 6, 2022. https://www.climbing.com/skills/should-you-train-full-crimped/

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.