Off-the-Wall Strength Training for Climbers: A Seasonal Framework

It seems like a new “best hangboard protocol” or “best training plan” emerges every day, promising to be the missing piece of the puzzle to help you send harder. Unfortunately, it’s common to see climbers taking these bits of advice, applying them to their own training for a couple of weeks, and then jumping ship when the short-term gains stop and progress plateaus. I want to discuss the true best training plan: systematic, long-term strength training. I’ll let you in on a little secret: a generalized “best training protocol” doesn’t exist. Every person is starting from a different place and has different goals, as well as different weaknesses to work on. The best training plan you can follow should be tailored to you as an individual and follow the principle of progressive overload. It should also be done consistently for a long time.

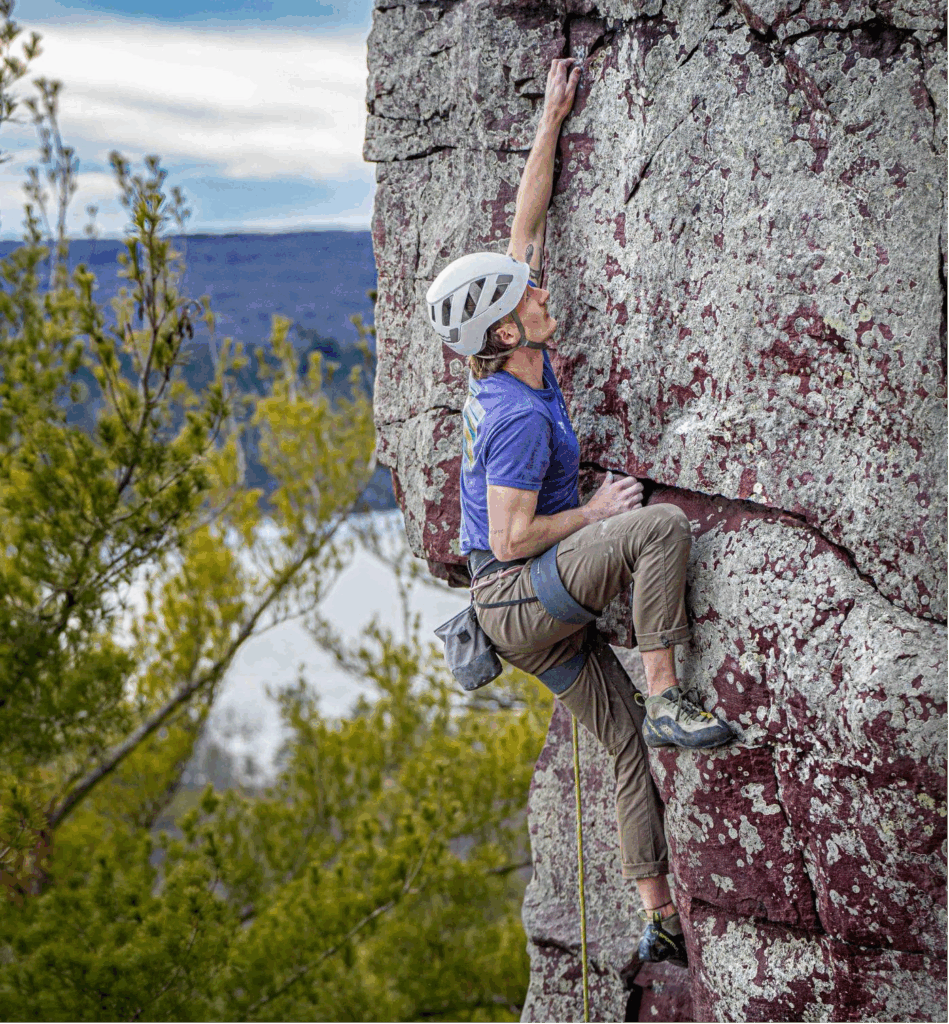

Just as the seasons ebb and flow, so should our off-the-wall training. In doing so we continue to challenge our bodies and ensure we are the most prepared for sending when the season arrives. Likewise, when that time comes, our off-the-wall training shouldn’t be thrown out entirely, as it can be just the extra boost we need when the temperature drops and the focus shifts towards hard projects. It can also help prevent injury and keep you healthier while pushing yourself on physically demanding projects. In this article, I will provide a framework for how this off-the-wall strength training could look throughout the year using the Strength Continuum and highlight the benefits of structuring your training in this manner.

Training Physiology

Before we dive into the Strength Continuum framework, it’s important to lay a foundation of training physiology. The cornerstone of any training program, whether focused on building strength or not, is the principle of progressive overload (Kenney 2020). When you start a training program, provided you are giving yourself enough of a challenge, you will feel fatigued. Over time, your body adapts to that level of challenge and, eventually, it no longer feels as difficult as it did previously. According to the principle of progressive overload, the only way to push continued improvement is to raise the level of the training so it is challenging again through higher intensity training, variation, or new stimuli. There are many different ways that athletes can raise that level of challenge, and those will be covered more later on. Practically, this involves choosing the parameters of an exercise – intensity (or how much weight), volume (ie. numbers of sets and reps), and rest time – such that you are challenged but not maxed out. This high intensity is what we are striving for, but it cannot necessarily be attained right from the onset of a new training program unless you have an extensive training history. You must build up to it through the principle of progressive overload. However, high intensity is relative, and if you are new to these principles and methods of strength training, you can train close to failure early on safely with proper technique and guidance and still see strength gains.

Strength is defined as the maximal force a muscle or muscle group can generate (Kenney 2020). It is typically measured through a 1-rep maximum (1RM), the highest amount of weight that can be lifted for a single rep of any given exercise. It’s been established that gains in maximal strength are optimal when training at a load that corresponds to 60-100% of 1RM with a low volume and long rest periods. Athletes with a more extensive training history require higher intensities to see greater gains in strength (Kenney 2020).

Training Goals |

Load (%1RM) |

Goal Repetitions |

|---|---|---|

| Strength |

≥ 85 |

≤6 |

| Power: Single-Effort |

80-90 | 1-2 |

| Power: Multiple-Effort | 75-85 | 3-5 |

| Hypertrophy | 67-85 | 6-12 |

Data from National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA)

A benefit seen in regular strength training is the effect of “injury prevention.” Now, I put that in quotes because there is some nuance to that statement. Acute injuries are often freak events. Sometimes you just land wrong or fall too far. However, there is compelling research suggesting that regular strength training has a protective effect. For instance, college athletes with a higher back squat 1RM are significantly less likely to experience a lower extremity injury in their sport (Case et al., 2020). Regular strength training can increase the overall resilience of your tissues, which might help protect you from overuse-related injuries. You could still see some protection from acute injuries that occur when a tissue’s capacity is exceeded suddenly (think the dreaded foot slip and popped pulley or tweaked shoulder). A 2014 meta-analysis found that strength training provided the biggest reduction in injury rates when compared to other exercise interventions such as stretching or proprioceptive training (Lauersen et al., 2014). Through consistent and progressive strength training, your muscles and tendons are able to produce more force and handle more overall training load (a function of volume and intensity). Those same tissues are now better equipped to handle the demands of climbing.

I contend that this is where the greatest benefit of regular strength training lies. We aren’t strength training to become powerlifters, and so our numbers in the gym only matter to track progression over time. What regular strength training does is increase your body’s ability to handle more overall load, and practice climbing more. Having a well-rounded and capable FULL body developed through regular strength training ensures that you can spend more time practicing climbing and avoiding injury. Sure, upper body pulling strength and finger strength are important in executing challenging moves, but in a sport that has such a large technical component, more time spent on the wall practicing moves on varied terrain is what is needed to ensure steady progression. Strength and technique aren’t independent: greater strength can help enable technical development. But realize that neither aspect is everything and there must be a balance of both.

This is where I’ll bring in my obligatory “strength isn’t everything, but it’s something” disclaimer. Yes, greater strength can make hard moves easier, but an issue I’ve noticed is that climbers who rely too much on their strength are often handicapping themselves in the realm of technical development because they don’t need to find the best beta possible to get through a section. Many climbers can get a long way relying on their strength to pull through moves, but at some point, they’ll meet a section that requires more than brute strength.

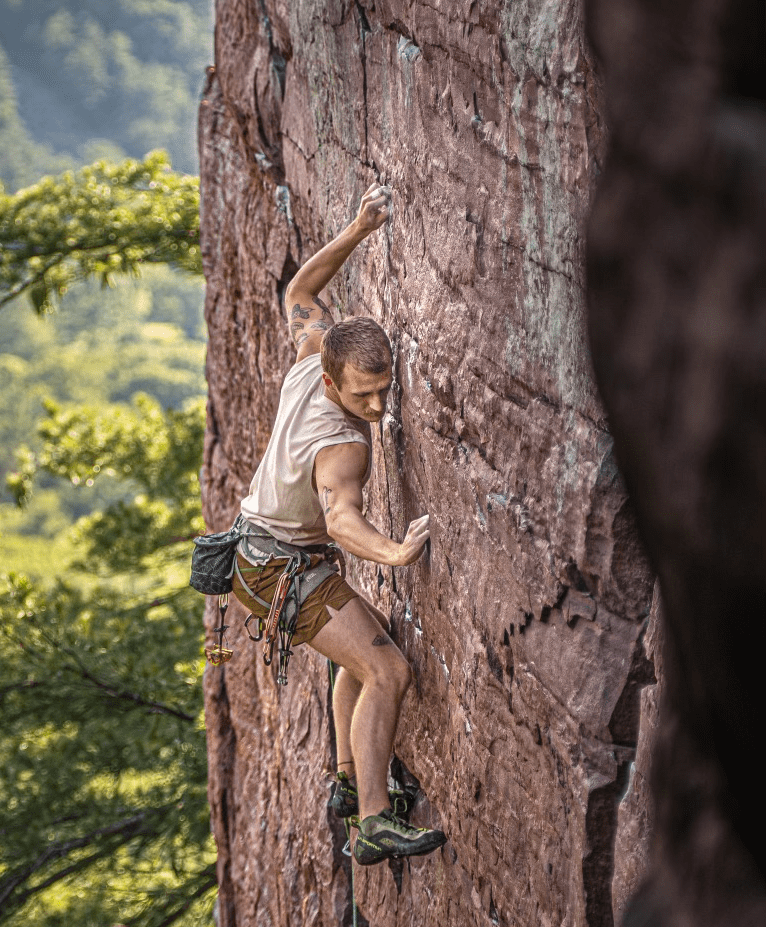

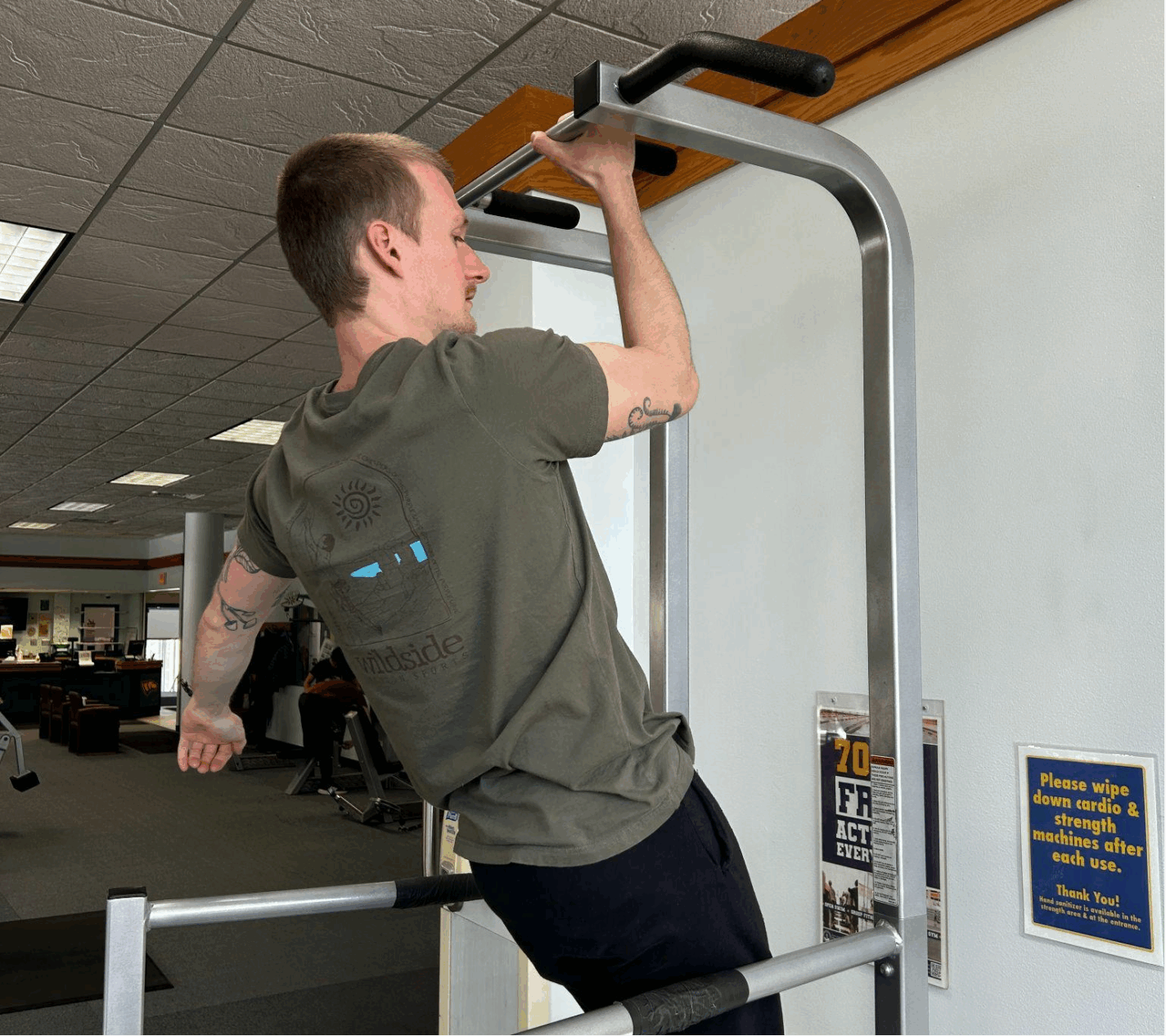

Author performing a deep lock-off at Devil’s Lake, WI, a move that requires a balance of strength and technique

I’ve also heard climbers, in a sport where strength-to-weight ratios are a consideration for some, avoid lifting weights for fear of putting on too much muscle and “bulking up.” However, gaining strength or muscle mass (a process called hypertrophy), is extremely challenging. It takes months, if not years, of dedicated effort. I’m sure none of you avoid driving a car because you’re scared of becoming a NASCAR driver. It’s the same for strength training. You won’t perform one training cycle and suddenly add ten pounds of muscle. Moreover, I wholeheartedly believe that most climbers could stand to put on some muscle for all the benefits already discussed, from increased strength to greater tissue resilience and capacity to handle training load. Strength gains often come quite quickly, and that comes from neuromuscular adaptations – essentially, your brain gets better at telling the muscle to work hard. The magic comes in sticking with a training program once the neuromuscular gains plateau out, and they naturally do. Lasting change won’t come through jumping ship to a new training program every few weeks when neuromuscular gains and apparent progress slows.

Periodization Overview

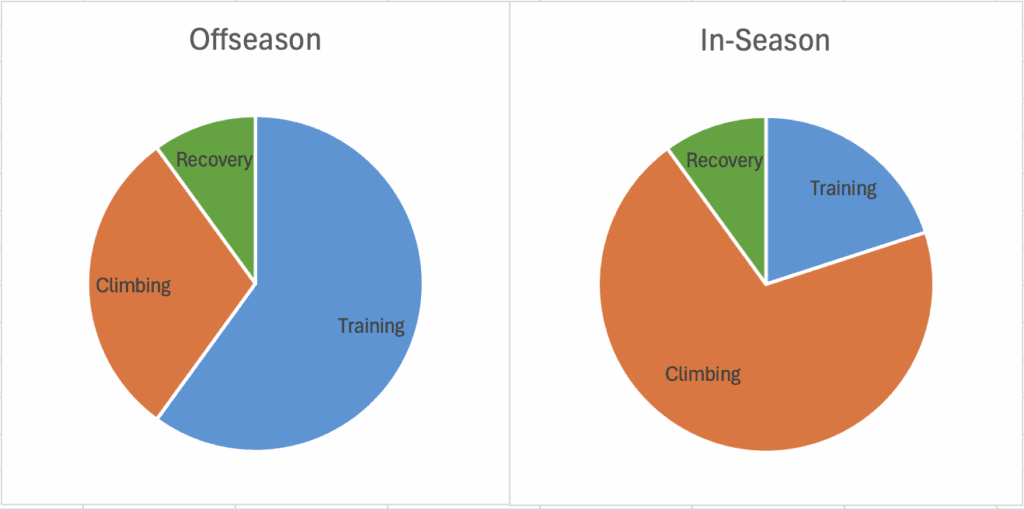

Periodization is defined as the planned manipulation of training variables (load, sets, and repetitions) to maximize training adaptations and prevent the onset of overtraining syndrome, a condition in which strength and endurance drop and athletes experience a whole host of symptoms from mental health issues to poor quality sleep and increased rates of sickness (Williams et al., 2017). Essentially, your body is pushed so deep into a hole that it can’t recover and starts giving out on you. There are many different periodization models to follow. However, the details of those different models are not only beyond the scope of this article but also, because (most) climbers aren’t training to improve at powerlifting, I would argue the level of granularity that would come with explaining those different models is not necessary for us unless you are the best of the best. The important takeaway from the different periodization models is that you should avoid training at maximal intensity with a high volume for much of the year, and that must be developed slowly. Periods of lower intensity and volume should also be factored in to avoid overtraining. I’ll use a pie-chart to illustrate this concept.

Throughout the year, different parts of your training, climbing, and recovery will take up different-sized pieces of that pie. They will (and should) change throughout the year. However, what doesn’t ever change is the size of that pie. You only ever have one pie to cut pieces from, so when one piece gets bigger, another piece must get smaller. Disclaimer: The diagram is not representative of how big those slices should be, that will depend on each individual. These merely illustrate the concept

The concepts from periodization models that are most relevant to discuss here are overload, variation, and specificity. Overload was defined previously in the article. Variation describes the manipulation of training variables that change the overload stimulus (Lorenz & Morrison 2015). Some of these variables are sets, reps, and rest periods, as well as exercise type and the prescribed intensity. It also refers to variation in exercise selection. This doesn’t mean changing exercises every week or two, but instead ensuring you avoid performing the same exercises for such a long time that the gains plateau. A loose guideline I like is that a specific session should be done at least 10 times in a training cycle but no more than 20 before changing things around a bit. Specificity can be loosely defined in a lot of different ways. How I will define it here is from a mechanical perspective, where attributes of the exercise performed more (or less) closely resemble the demands of the sport. These attributes may be muscular contraction type (eccentric-concentric or isometric), rate of force development (rapid or slow), and amplitude and direction of movement (Lorenz & Morrison 2015). In the following section, the different aspects of the Strength Continuum will be described according to some of these concepts.

One last point I want to talk about regarding periodization is simplicity. We’ve all heard of the KISS principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid). It can be fun to dive into all the details of periodization and meticulously craft the most “perfect” program. Ultimately though, what matters is consistency. These complicated methods of periodization, load manipulation, and other training strategies should be reserved for elite-level athletes who have exhausted all other avenues to improvement. Put together a simple program that you’ll stick with and progressively overload your body, focus on sleeping well, recovering between sessions, fueling your body well and, perhaps most importantly, sticking with it for a long time, and you’ll be amazed at how far you go.

The Strength Continuum

The Strength Continuum is a concept I first encountered in a video from Steve Bechtel at Climb Strong. It provides a rough framework for off-the-wall strength training that varies throughout the year according to the seasonal nature of outdoor rock climbing and performance. I will discuss some key principles put forth with this model, add some of my own insights, and use a couple of different exercises as examples throughout to show how these concepts could be integrated into a training program.

General Strength |

Stability Strength |

Specific Strength |

|---|---|---|

| High loads High CNS demand Highest stability |

Medium loads Sport-specific integration Medium stability |

Lower loads Sport simulations Lowest stability |

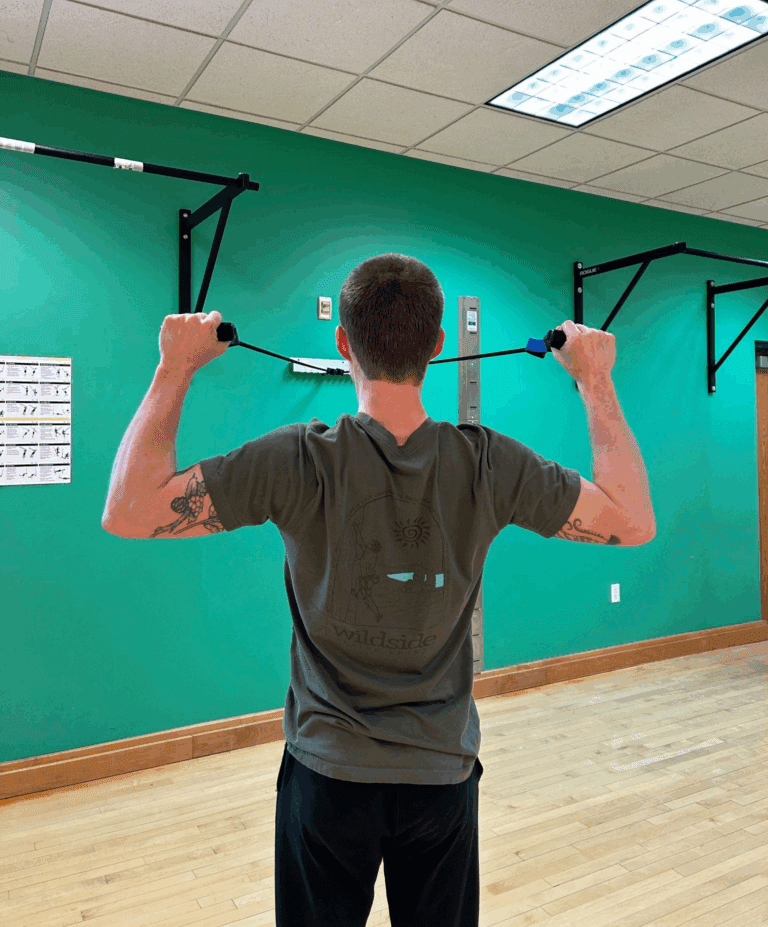

The Strength Continuum consists of three distinct phases, referred to as General Strength, Stability Strength, and Specific Strength. I like the names of these phases and will continue to use them in this article as I feel they highlight the hallmark characteristic of each phase and show the progression across the continuum. They are different in the stability requirements of the exercises and, correspondingly, the loads used. In strength training, common exercises used to increase the maximal force output of a muscle are often highly stable (think a bench press, squat, or deadlift). This means that little effort is needed to control the movement and instead can be directed into moving as much weight as possible. As exercises become less stable, such as single-arm or single-leg exercises, the maximal force output possible (and, as such, the external load) must drop because more effort must be expended to control the movement. Note, that doesn’t mean the movement is easy, it certainly should still be hard or challenging. It’s just that, by nature, the maximal force output from a muscle or group of muscles will drop as an exercise becomes less stable. As I describe each phase, I will use pull-ups and squats to highlight the specifics of each.

High loads and highly stable exercises characterize the General Strength phase. This phase doesn’t compose much of the overall training year: a short 4-6 week block in the winter and perhaps an equal length one in the heat of the summer if conditions are less conducive to hard projecting, or after returning from a long climbing trip and getting back into a training program. The goal is to overload these stable movements and drive up the overall force-producing capabilities of the muscles. There should still be some climbing volume during this phase, but the majority of the pie is taken up by off-the-wall training in the weight room. This training won’t necessarily look like climbing, and that’s okay!

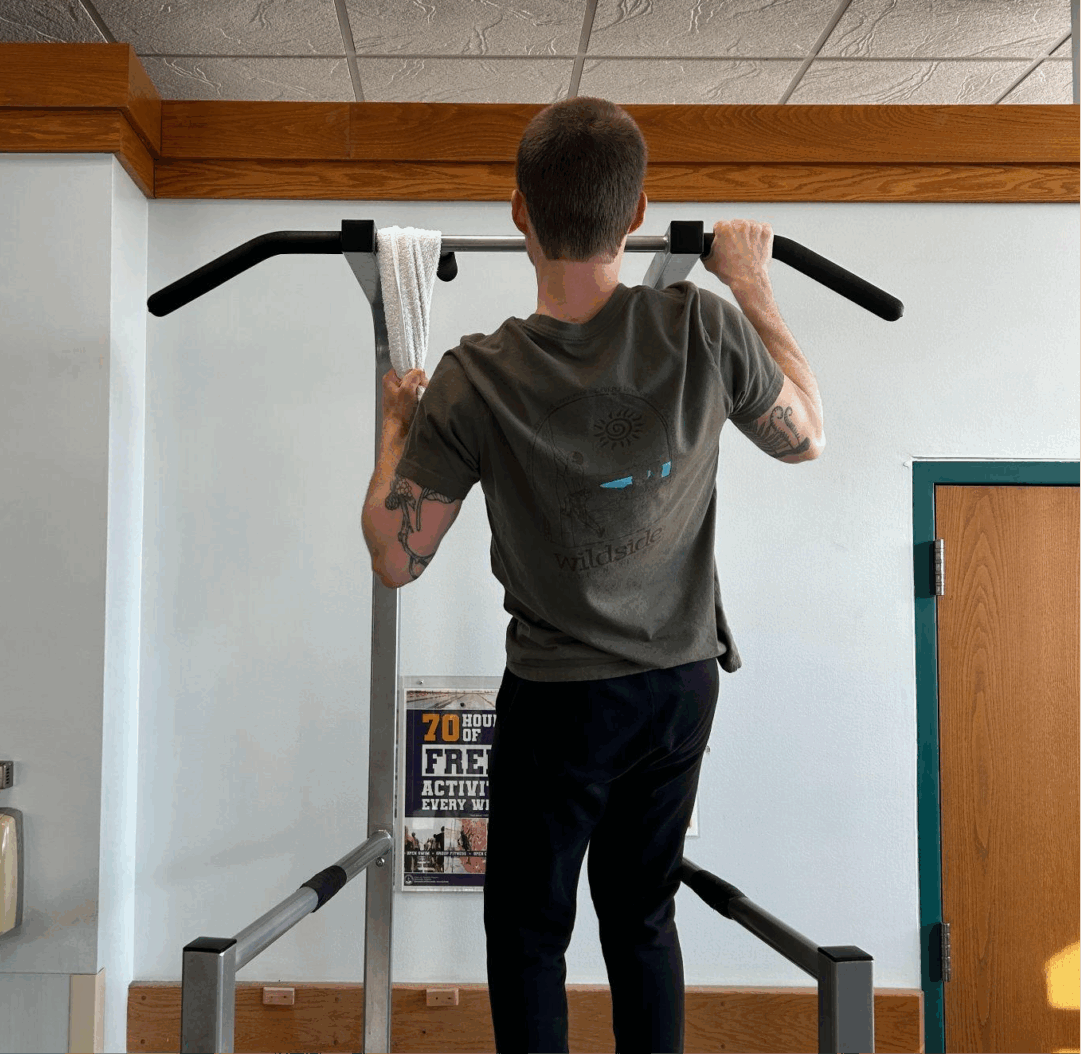

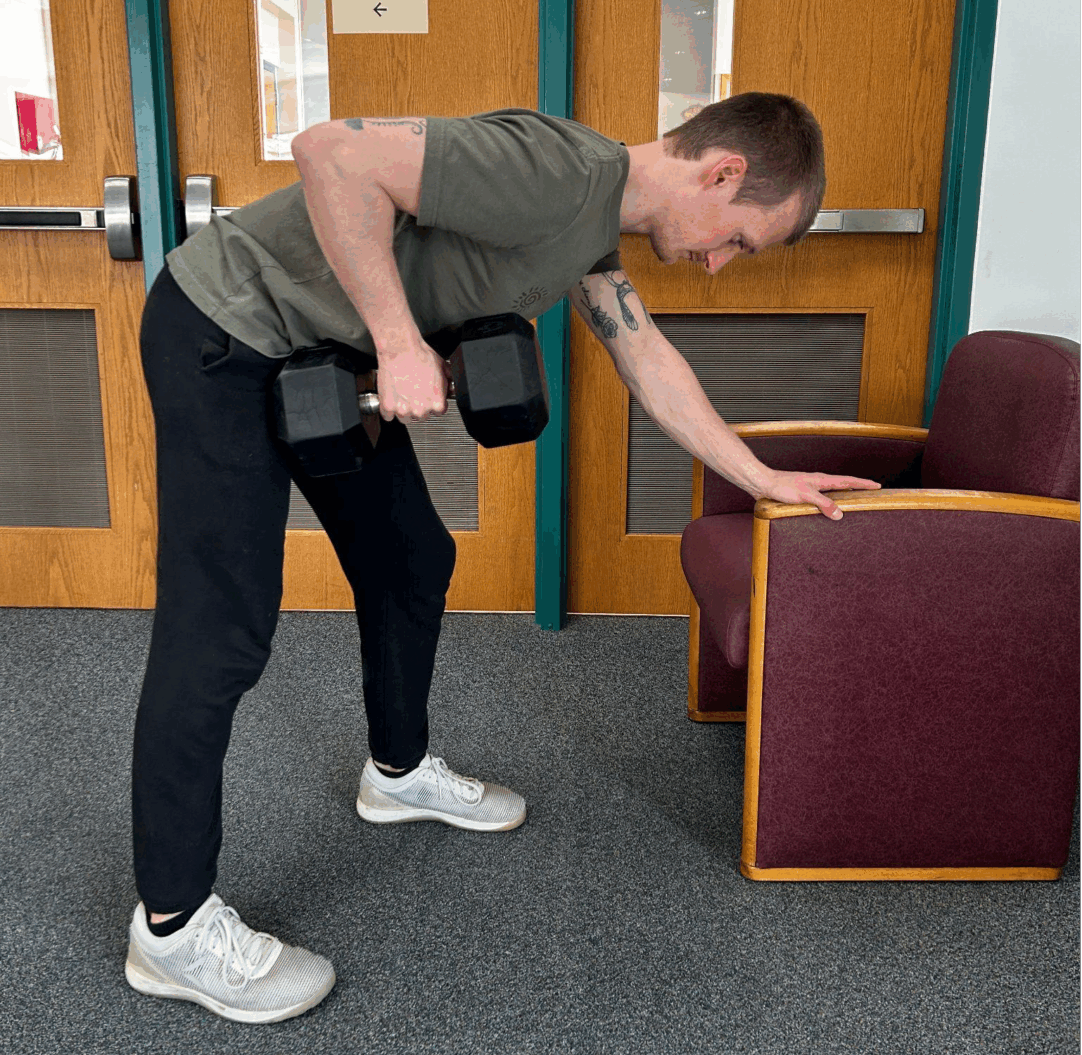

You’re looking at 3 days per week in the gym, focusing on 10-15 reps total for each exercise. I like having somewhere in the ballpark of 5 sets of 2-3 reps. I can’t make specific recommendations of what exercises to do and how many to perform. Still, I will say that exercises should focus on major muscle groups or movement patterns, such as horizontal and vertical pulling and pressing with the upper body, as well as hinging and squatting with the lower body. I generally like 2-3 upper body exercises and 1-2 lower body exercises in each session, on top of any mobility or accessory work. These should be HEAVY, again the goal is to drive up the overall force-producing capabilities of the muscles. This is where a standard bar pull-up (or weighted pull-up) and a stable squat variation, such as a back, front, or Goblet squat (shown below) are required. If these more “traditional” powerlifting-style exercises are unfamiliar, spend some time getting familiar with the movement and start with a challenging yet conservative load, continuing to near failure to elicit strength gains as mentioned previously.

For those who are familiar with these movements, following the “last set max reps” rule can ensure that the load is consistently challenging. On the last set of an exercise for the week, do as many reps as possible with the prescribed weight you are using, instead of stopping at the prescribed number of reps. If you are able to complete more reps than was prescribed, increase the load the following week. If you can’t complete all of the prescribed reps on the final set, that’s a sign you’re at the right weight and should stick with that the following week.

The Stability Strength phase is characterized by medium loads and exercises that are a bit less stable than the previous phase. This is also the phase where we start to see some sport specificity coming into play. Much of the year is spent in this phase, after a general strength phase and before short periods of maximal performance. Where the goal of the previous phase was to move heavy loads, the goal in this phase is to maintain perfect form throughout the exercise. The weight should be challenging but not where you’re barely eeking out all of the reps; the last rep should look very similar to the first rep of each set. With my athletes, I like to prescribe a subjective 8/10 ‘effort’ rating, as opposed to recommending a specific load.

Explosive pull-ups, offset pull-ups, single-arm rows on the rings or with a dumbbell, and split squats are all exercises that would live in this phase. They are slightly more unstable than the previous phase, and as such the maximal force output in these exercises is a bit lower. You’re looking at 1-2 days per week in the gym, 2-3 sets per exercise, and sets should be somewhere in the 5-10 rep range. As mentioned above, I like 2-3 upper body exercises and 1-2 lower body exercises in major movement patterns that rotate and encompass the whole body over the week. If you are a weekend warrior and are not focused on climbing three, four, or even five days a week, you might benefit from 2-3 days a week of this style of training. Regardless of whether you are in a pre-season period or actively in-season, climbing will take up a bigger piece of the “training pie” in this phase, and we don’t want to be leaving the gym with excessive soreness, so don’t overdo the volume.

The Specific Strength phase is characterized by low loads and highly unstable exercises, as well as exercises that are even more specific to the demands of the sport. The duration of this phase will be inversely proportional to the previous phase: if most of your year is spent in the Stability Strength phase, then this phase will be reserved for periods of max performance, and vice versa. The decision for how much of the year this phase and the previous phase should take up is highly dependent on the individual.

Specific board climbing where you move slowly, focusing on using big foot holds and controlling small or challenging hand holds (often referred to as “wall crawls” or “crimp crawls”), lock-offs on a hangboard or pull-up bar, and pistol squats are all exercises for this phase, as they are the most unstable variations of exercises throughout the program and most specific to the demands of rock climbing. As such, the focus should be on high-quality movement, as it can be risky to perform these exercises poorly.

These sessions will only occur 1 day a week with a low session volume, 2-3 sets of few reps per exercise. Because you are stressing the same tissues that are stressed heavily in a performance phase, there is a risk of overdoing this type of training. More is not the answer here. For any weight training, perform full-body sessions with 2-3 upper-body exercises and 1-2 lower-body exercises in each. This is the type of training you’ll do during performance phases where most of your “training pie” is dedicated to performing on rock, so make sure your focus is directed at climbing. Don’t try to be the training hero here constantly pushing for more; that’s a recipe for injury with the exercises in this phase! These sessions function to maintain strength with minimal time spent in the gym.

I hope this provided a brief but informative overview of this framework for organizing your off-the-wall strength training over a year. Since this is more of a 30,000-foot look at this type of training, I would direct anyone curious about off-the-wall strength training to read the book Unstoppable Force by Steve Bechtel and Charlie Manganiello, as it gives a breadth of applicable information on how to structure individual training sessions and cycles.

When to See a Physical Therapist

The information provided here is for educational purposes and is not medical advice. Please schedule an appointment with a licensed physical therapist or a qualified strength and conditioning specialist for more guidance and specific recommendations on training for climbing or if pain is limiting you from loading heavily with a strength training program.

References

- Kenney, W. L., Costill, D. L., & Wilmore, J. H. (2020). Physiology of sport and exercise. Human Kinetics.

- Case MJ, Knudson DV, Downey DL. Barbell Squat Relative Strength as an Identifier for Lower Extremity Injury in Collegiate Athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(5):1249-1253. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003554.

- Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British journal of sports medicine, 48(11), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092538.

- Williams, T. D., Tolusso, D. V., Fedewa, M. V., & Esco, M. R. (2017). Comparison of Periodized and Non-Periodized Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 47(10), 2083–2100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0734-y.

- Lorenz, D., & Morrison, S. (2015). CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIODIZATION OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR THE SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPIST. International journal of sports physical therapy, 10(6), 734–747.

Author Bio

Michael Larson is a second-year Doctor of Physical Therapy student at UW-Stevens Point in Wisconsin who will graduate in the winter of 2025. He loves all things outdoors, but especially rock climbing. He spends most of his time trad climbing and bouldering on the purple quartzite of Devil’s Lake. He also enjoys weightlifting and has maintained a small online personal training business for the past few years.

After graduation, he plans on serving an athletic population, including outdoor athletes, and is open to wherever the profession of physical therapy takes him.

If you have any questions about these concepts or their application, feel free to reach out to michaellarson433@gmail.com.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.