Lower Body Training & Performance for Climbers

So you want to get better at climbing. You spend hours looking up hangboard routines and finding the latest and greatest grip strength devices, but what about your lower body? There’s a reason why beginner climbers are told to climb with their feet. Our lower bodies are the unsung powerhouse of climbing. Heel hooks, high steps, and drop knees are all valuable climbing techniques that are made possible by having not only strength, but the range of motion to actively move in and out of these positions on the wall.

What is Active Range of Motion?

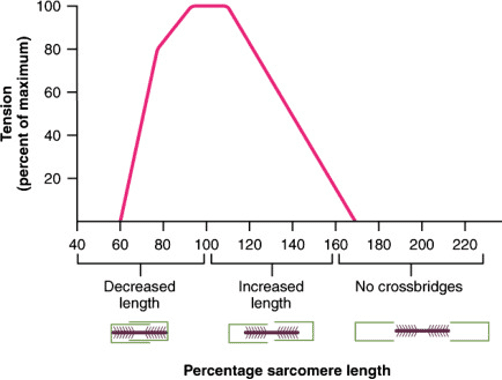

Range of motion can be described as the capability of a body part to be moved around a joint. Active range of motion is achieved when opposing muscles contract and relax resulting in joint movement. For example, when you bend your elbow towards your shoulder like a bicep curl your biceps need to contract while your triceps relax and lengthen. Our muscles can be limited in extreme positions because they are weaker when they are in an end-range elongated or shortened position. The force length relationship outlines that our muscles are strongest in the mid-range. However, we can train our bodies to be stronger at differing ranges which can be a benefit to climbers as we often find ourselves outside of the optimal mid-range of a muscle. Additionally, muscles producing force at lengthened position are at risk for strain, so improving their strength can help with injury prevention.

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.873370/full

An eccentric contraction can be described as a “lengthening contraction”. An eccentric contraction shows significant improvements to both flexibility and strength in the muscles of the lower body, which can not only help with moves that require extreme ranges of flexibility like drop knees and heel hooks, but work to offload the weight from our upper body.

Hip Anatomy

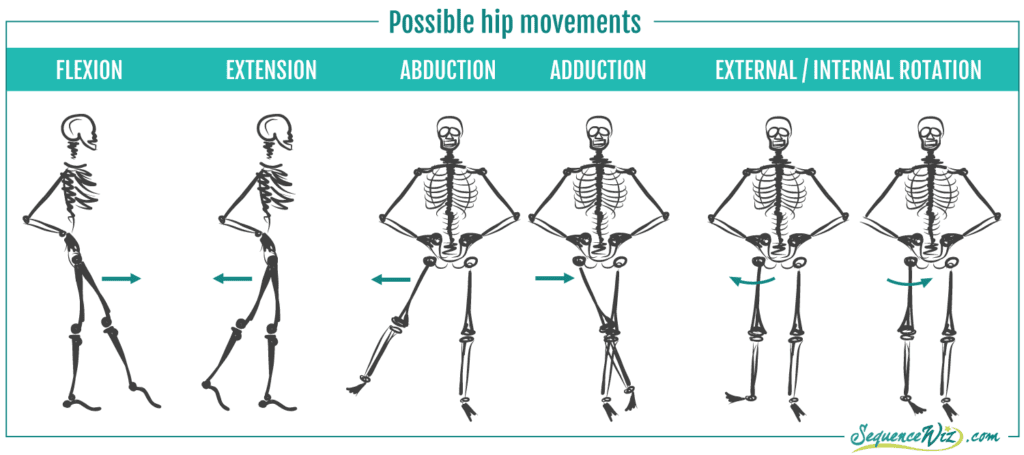

The femur (also known as your thigh bone) connects to the hip socket, called the acetabulum. The hip socket is located in the pelvis. The head of the femur resembles a “ball” that fits into the hip socket and forms a ball socket joint also known as the hip joint. This anatomy allows our hip to move forward and back (flexion/extension), across and away (adduction, abduction) and in and out (internal and external rotation).

(source: https://sequencewiz.org/2015/09/09/tight-hips-solution/hipmovements-2/)

Many climbing moves involve extreme ranges of motion/flexibility and strength such as high steps, heel hooks and drop knees. Increasing your active range can help improve positions for rest, provide different beta options, and make your climb more efficiently. Having good strength and flexibility of your hips will help keep them closer to the wall, which in return can help offload the weight from your upper body.

High Steps

A high step involves raising your leg to a high foothold where you then load and shift onto in order to progress up to the next holds. High steps are common on slab climbs where footholds can be hard to come by, requiring the climber to raise their foot up very high to reach them. In order to do a hip step you need strength of the hip flexors to raise the foot/knee and length/flexibility of the hip flexors on the opposite leg. If the hip flexors are not strong enough or the hip is too stiff into flexion, the body will compensate by bending the opposite leg and pushing the hips back from the wall, inevitably making you fall off the climb.

Isometric Lift Offs: 3 sets of 10 repetitions x 1-2 sec hold (each side)

Long Lunge: 3 sets of 10 repetitions x 1-2 sec hold (each side)

Banded Psoas March: 3 sets of 10 repetitions x 1-2 sec hold (each side)

Heel Hooks

A heel hook involves placing your foot on a hold or ledge and applying pressure with the heel of the climbing shoe. This movement allows you to pull your body in towards the wall using your leg muscles. This action involves having a significant amount of hamstring strength in a lengthened position as well as strength of the external hip rotators like your glutes. This movement places a substantial amount of demand on the posterior, often requiring special attention in training to improve the strength and resilience of these muscles. By strengthening these muscles in lengthened positions it helps to prevent injuries, keep your hips closer to the wall and offload weight from your upper body.

Modified Glute Bridge: 3 sets x 8 repetitions

Hamstring curls on Ball: 3 sets x 8 repetitions

Elevated Single Leg Romanian Deadlift: 3 sets x 8 repetitions

Drop Knee

A drop knee is a footwork technique that involves weighting the outside of one foot with the opposing foot stemming against another hold order to generate body tension. The position involves rotating the corresponding hip towards the fall and the knee downwards. The drop knee is useful for generating stability and power from the hips and helps to increase your reach to far away holds. Despite the name, the drop knee entails flexibility and strength of the internal hip rotators.

90/90 Lift Offs: 3 sets of 10 repetitions x 1-2 sec hold (each side)

Raised Modified Lunge: 3 sets x 8 repetitions

4-Point Band Assisted Internal Rotation: 3 sets of 10 repetitions x 1-2 sec hold (each side)

On-the-Wall Training

Isolated practice on the wall can is a great way of strengthening your muscles at different lengths. Seek out holds where you can practice high steps, heel hooks and drop knees on the wall.

See a Physiotherapist

If you find pain or pinching during these exercises or think aspects of your climbing may benefit from being addressed, see a physical therapist. Seeing a physiotherapist who’s familiar with climbing can not only help you improve your climbing but can work with you to develop a training regime focused on your deficits and will help prevent future injuries.

The lower body is often forgotten about in climbing, but it shouldn’t be overlooked. Training your lower body strong over a range can not only improve your performance, but help prevent injuries, keeping you on the wall climbing – which is everyone’s goal at the end of day.

Resources

- Brughelli, M., & Cronin, J. (2007). Altering the length-tension relationship with eccentric exercise : Implications for performance and injury. Sports Medicine (Auckland), 37(9), 807–826. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737090-00004

- Marušič, J., Vatovec, R., Marković, G., & Šarabon, N. (2020). Effects of eccentric training at long‐muscle length on architectural and functional characteristics of the hamstrings. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(11), 2130–2142. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13770

- Vetter, S., Schleichardt, A., Köhler, H.-P., & Witt, M. (2022). The Effects of Eccentric Strength Training on Flexibility and Strength in Healthy Samples and Laboratory Settings: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 873370–873370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.873370

- Wolf, M., Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Fisher, J. P., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Steele, J. (2023).Partial Vs Full Range of Motion Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning

https://doi.org/10.47206/ijsc.v3i1.182

Author Bio

Morgan Yont is a second year Master’s of Physiotherapy student at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. She has a strong interest in outdoor sports and hopes to treat athletes of all levels in her future. When she’s not in school she can be found rock climbing, backpacking, skiing, taking photos, or hanging out with her dog.

Instagram: @livingwitharlo

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.