How To Rehab a Climbing Finger Pulley Injury

In this post, we’ll review the rehabilitation guidelines for a pulley sprain. Based on the research by Lutter and colleagues as well as Cooper and colleagues.

First, lets review the grading of an injury with ultrasound from a study by Lutter and colleagues. As you can see in the table below, pulley injuries are graded, based on ultrasound evidence, as Grade I, II, III, IVa, or IVb.

| Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV a/b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretching or Slight Tearing | A3 or A4 Complete Rupture A2 Partial Tear | A2 Complete Rupture | Multiple Complete Ruptures |

These rehabilitation timelines and categories were based on the grading of pulley sprains. This is grading with ultrasound imaging; you can also use CT scan or MRI. But what if you don’t have access to ultrasound imaging? What if you can’t grade the pulley sprain from I to IVb? Then you can use clinical criteria, also developed by Cooper and colleagues, and as you can see in the table below, the characteristics of these clinical criteria are Mild, Moderate, and Severe. The influence of pain on daily living and function, active range of motion, manual muscle testing, and pain with palpation make up the clinical criteria to grade the severity of a pulley injury.

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|

|

Daily Living: 0/10 does not limit activity Climbing: ≤ 2/10 after climbing only crimp grip is painful |

Daily Living: 3-5/10 does not limit activity Climbing: ≥ 5/10 that limits climbing in all grip positions |

Daily Living: 5/10 limits activity Climbing: > 5/10 that severely limits climbing |

| Pain at end range finger flexion with no AROM loss | Pain at end range finger flexion with ≤ 25% AROM loss | Pain and >50% limited ROM with finger bending and straightening |

|

Sloper: 0/10 Half crimp: ≤ 2/10 Full crimp: ≤ 2/10 |

Sloper: ≤ 2/10 Half crimp: 2-5/10 Full crimp: 6-8/10 |

Pain and weakness with any resisted flexor muscle test or “grip” hand position |

|

Minimal pain with full blanching palpation (maximal pressure) |

Pain with mild blanching palpation (moderate pressure) | Pain with no blanching palpation (minimal pressure) |

So let’s take a deeper look at each of those grading criteria so that you have a better understanding of the injury. Because once you know the grade or severity of the injury, you can then determine how best to treat it. See below for a video walking through the two methods to determine the grade or severity of a pulley injury.

How to Rehab The Injury Based on Grade or Severity

If you are using ultrasound the determine the grade of injury, it is rather straightforward to determine your recovery timelines since that is the gold standard assessment. However if you are using the clinical criteria to the severity of injury, it is important to know there is no correlation in research between the ultrasound’s degree of bone-tendon distance and the clinical findings of Mild, Moderate, or Severe. However, use the clinical judgment of a medical provider when identifying which category to rehabilitate in. For example, you could group the below degrees and severities together. When in doubt, always error on the side of being more conservative,

- Grade 1 or Mild

- Grade 2 or Moderate

- Grade 3 or Severe

If you look at the table below, you can see the clinical criteria of a Mild or a Grade I pulley sprain and the timelines associated with returning to both hangboarding and climbing. In the middle, you can see the yellow column for Moderate or Grade II, and then at the far right, the Severe or Grade III column. On the far left, you can see the criteria for climbers to return to: No Pain Hang Stage 1, Easy Climbing, No Pain Hang Stage 2, Moderate Climbing, Low Pain Hang Stage 1, Hard Climbing, and Low Pain Hang Stage 2.

Simply put, the hanging criteria below are defined as the below. These categories with be discussed in more depth later in the article in the strength section.

- “No Pain Hangs” are loading the fingers on a hnagboard or a portable training device with NO PAIN

- “Low Pain Hangs” are loading the fingers on a hnagboard or a portable training device with 2-10 PAIN

|

|

Mild or Grade 1 |

Moderate or Grade 2 |

Severe or Grade 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

No Pain Hang Stage 1 |

Week 1-2 |

Week 2-4 |

Week 3-6 |

|

Easy Climbing |

Week 2-3 |

Week 4-6 |

Week 6-9 |

|

No Pain Hang Stage 2 |

Week 2-3 |

Week 4-6 |

Week 6-9 |

|

Moderate Climbing |

Week 3-4 |

Week 6-9 |

Week 9-12 |

|

Low Pain Hang Stage 1 |

Week 3-4 |

Week 6-9 |

Week 9-12 |

|

Hard Climbing |

Week 5-6 |

Week 9-12 |

Week 12-15 |

|

Low Pain Hang Stage 2 |

Week 5-6 |

Week 9-12 |

Week 12-15 |

To define easy, moderate, and hard climbing, you can refer to the table below. Determining the intensity of a climb and the stress on the fingers is not an exact science, so it is recommended that you work with your medical provider to determine the best categories for returning to climb. However, the below can be used as a reference

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Easy Climbing |

Avoiding half and full crimp using large holds on faces not angled beyond vertical, 2 full grades below onsight (5.12 -> 5.10, V8 -> V6) |

|

Moderate Climbing |

Beginning to use half crimp on routes with mild angle beyond vertical 1 full grades below onsight (5.12 -> 5.11, V8 -> V7) |

|

Hard Climbing |

Using crimps on routes with angle beyond vertical Can climb up to onsight level (5.12 -> 5.12, V8 -> V8) |

Now that we understand the grading of the injuries using ultrasound and clinical criteria, as well as the research on return to sport timelines, We have to look to see how they can progress through a rehabilitation pyramid (see the diagram below from the book Climb Injury-Free). We start with unloading the tissues, and we move on to mobility. We go further go into strength and muscle performance, and then we retrain movement. This is the formula to return a climber back to sport after a pulley injury.

Unload The Tissues

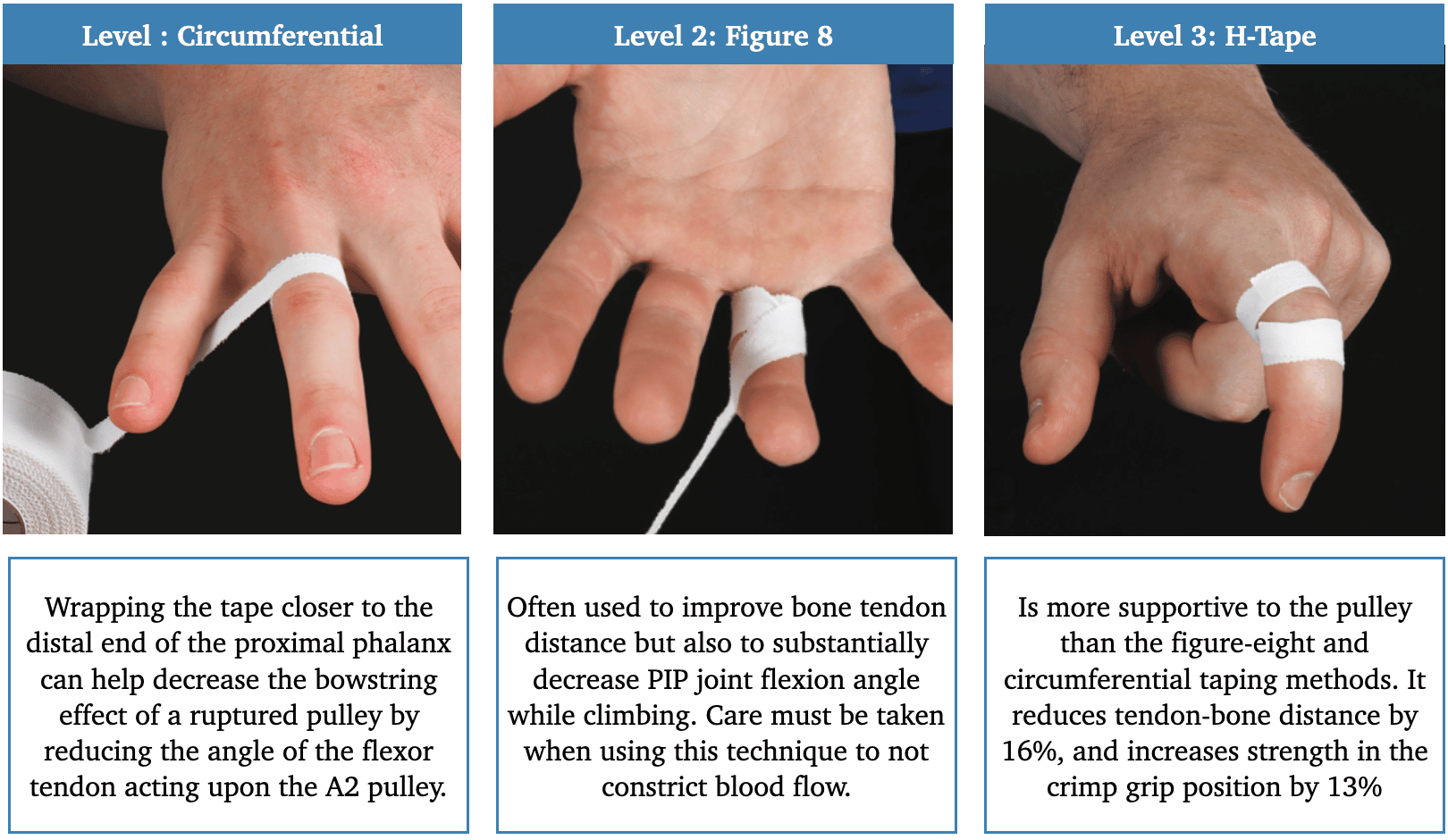

Let’s look at the base level of the pyramid, unloading. There are four different ways to unload. As you can see in the image below, the first three ways are using tape to improve bone-tendon distance. On the far left is circumferential taping, in the middle, figure-8 taping, and on the far right, H-taping. These three different techniques provide different levels of support to the pulley.

- For the circumferential technique, wrapping the tip closer to the distal end of the proximal phalanx can help decrease the bowstring effect of a ruptured pulley by reducing the angle of the flexor tendon acting upon the pulley.

- The figure-8 taping technique is often used to improve bone-tendon distance, but it also substantially decreases the PIP joint flexion angle while climbing.

- The H-taping is more supportive to the pulley than the figure-8 and the circumferential taping methods; it reduces the bone-tendon distance by 16% and increases the strength in the crimp grip by 13%.

So these three taping techniques have the potential to reduce bone-tendon distance, whether for wall climbers performing exercises or for those who are actually climbing. The least supportive technique is the circumferential; the middle-range supportive technique is the figure-8, and the most supportive is the H-taping, which improves bone-tendon distance, primarily acting at the level of A3 to approximate the area of maximal bowstringing. In effect, this then unloads A2 and A4. So these are the tape jobs that are recommended to improve bone-tendon distance in a climber who has a pulley sprain.

But a more aggressive way to improve bone-tendon distance even further is Unload Level 4, a pulley protection splint. See below for a video demonstrating how to make the splint.

A pulley protection splint is a thermoplastic ring that wraps around the finger and is custom fit to adhere or to press the tendon closer to the bone. In the image above, you can see a fabricated pulley protection splint. Wearing this type of splint during exercises and throughout the day is highly effective for anyone who is returning to climbing after a pulley sprain. The benefit of a pulley support splint has been supported in research.

In one study, Micha Schneeberger and his colleagues looked at forty-seven complete pulley ruptures in forty-five different rock climbers. They used a pulley p