Hormone Cycles and the Female Rock Climber

At the base of the climb, you tighten your harness over a tender, bloated stomach. The discomfort makes you irritable. In your mind, you start blaming your climbing partner for dragging you out of bed. The morning chill reminds you of where you could have been, that is, lying in bed with a hot pack and stash of chocolate watching the newest rom com on Netflix. But it is fine. You are fine. Everything is fine. You love climbing. Irritated over the fact you’ve been in a funk for the last few days, you take a few deep breaths. Tears mist your eyes, but you will not let your hormonal body cloud an otherwise sunny day. After popping a Midol, you pull on with determined resolve.

Immediately it feels like you’re battling the rock, even though you’ve completed this section of the climb many times before. Your fingers feel weak, and the contraction of your abs sends cramping pain through your pelvis and core. Far more stressed than usual, you desperately move your way upwards fighting off the pump. The next clip is just out of reach. So close, but so far. You nervously sweat and your lax-feeling fingers start to slip.

Nearly every female can relate in one way or another to the emotional and physical experience of having a period. For some it’s a nuisance, for some a relief, and for others a disappointment. From the beginning of puberty, the little red friend, or demon, has shown up monthly, and will continue to come until pregnancy or menopause for those who menstruate. In middle school health class, the menstrual cycle was introduced as a 30+ year companion, but its impact was never truly discussed again. The average female could feasibly have 500+ periods in a lifetime, that is ~3,500 days menstruating. A grand total of 9.6 years of their life is spent solely battling the Crimson Tide, and I don’t mean Alabama football.

Hormone fluctuations throughout the month can impact mood, motivation, and even musculoskeletal structures. Whether one feels dramatic changes throughout the month or maybe a blip of change here and there, many have considered how the menstrual cycle affects climbing performance. The first step is to learn what is going on in the female body and then look at the current research to make the best decisions.

So, what’s going on down there?

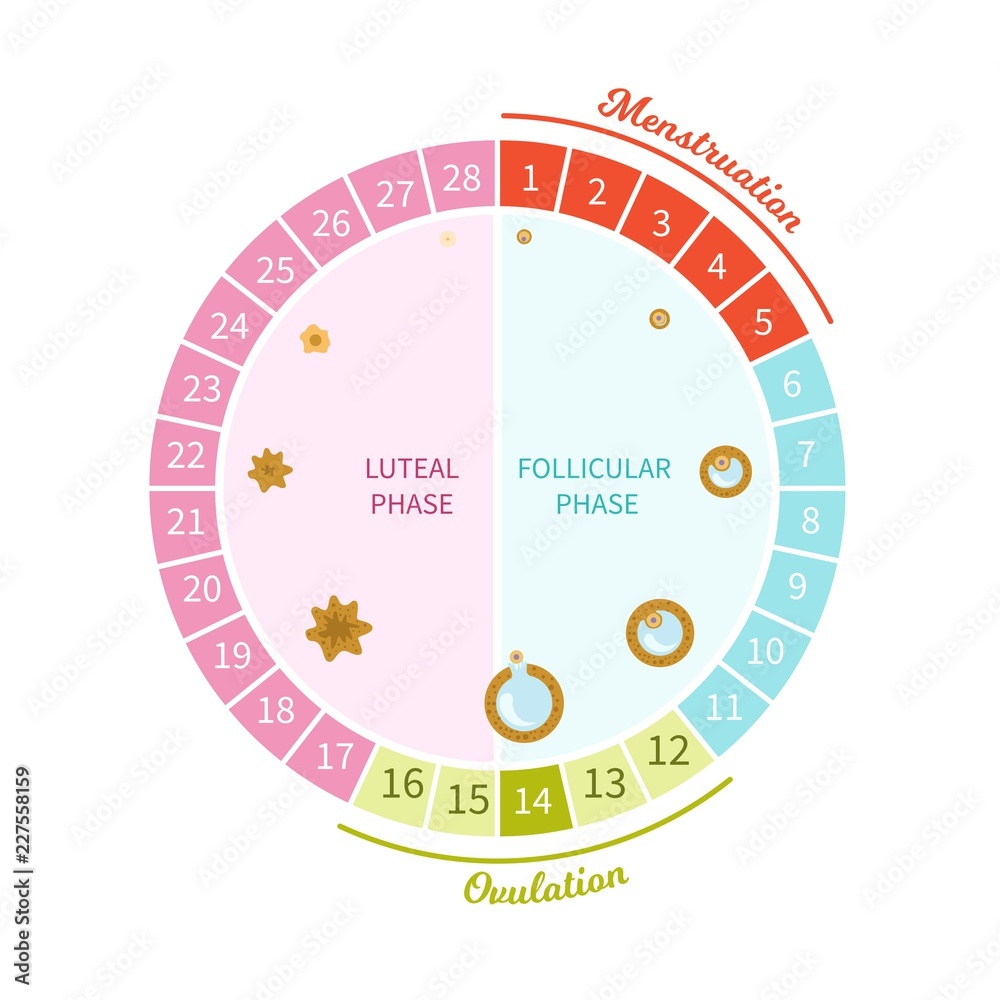

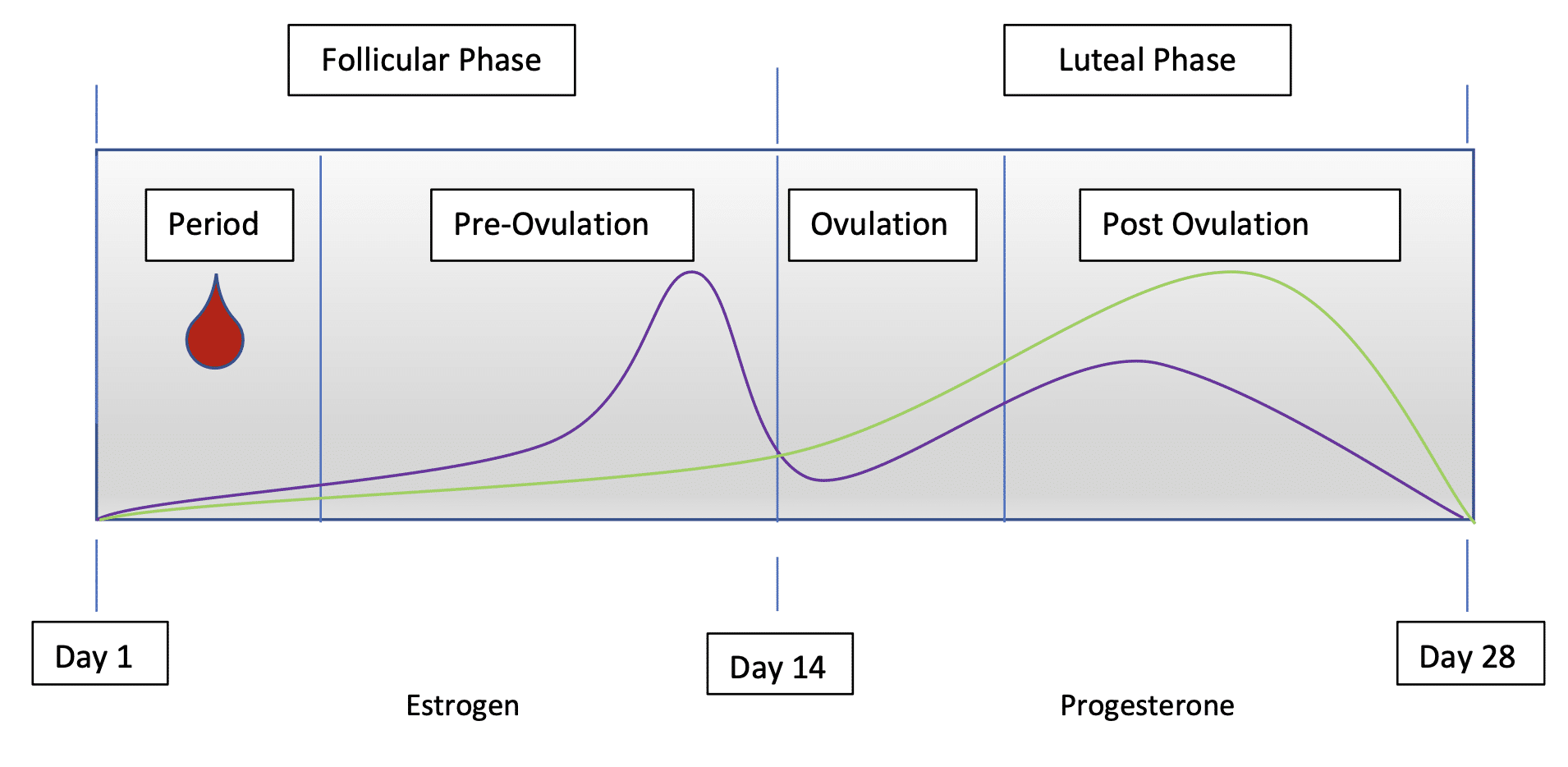

The menstrual cycle repeats every 20-35 days, with an average around 28 days. Two predominant phases occur within the cycle: the follicular phase and the luteal phase. The whole shebang begins with the first day of a period, which marks the beginning of the cycle and follicular phase. A period, aka. menses, generally lasts anywhere from 5 to 7 days. This process occurs once the potential for pregnancy has passed, the uterus will shed its endometrial lining, and then it exits the body.1

Following menses, the body has a spike in estrogen hormone. Estrogen signals the ovaries and uterus to prepare for ovulation by telling follicles within an ovary to ready an oocyte (egg). The process takes about 7 days and can be thought of as pre-ovulation. Around day 14, ovulation begins when the oocyte is released from the ovary into the fallopian tube. Ovulation lasts about 3-5 days, marking the end of the follicular phase and the beginning of the luteal phase. For the next 8-12 days, post-ovulation, progesterone is released, and the endometrial lining of the uterus thickens in preparation for the implantation of a fertilized egg into the uterine wall (i.e. pregnancy).2

However, if the window of ovulation is missed, or intentionally avoided via contraception, the body will experience a rapid decline in hormone secretion of estrogen and progesterone resulting in the subsequent sloughing of the endometrial lining. During this post-ovulatory interval, the reproductive system prepares for menses and the cycle starts over.

Typical Period Timeline

Menstrual Phases and Climbing

The stage of the menstrual cycle and its correlated hormones can impact your physical and psychological performance on the wall and in life. It is important to point out from the get-go that menstrual cycles and the experience associated with them are highly individual. So, where does that leave us? Well, the gap in the literature creates a beautiful space to design exactly what female bodies need for training, rest, and performance. A completely individualized approach means there is no box to fit in, no measuring stick, no scale, or any other analogy. There are tips for what may work during each phase; however, be sure to consider the individual and their personal experience.

Late Luteal & Early Follicular – PMS & Period

The last 1-2 weeks of the luteal phase is a time when hormone levels are at their lowest and the body is preparing for a period. Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) is very common at this point in the cycle and consists of a myriad of unfortunate symptoms with the most common being mood swings.3

Common PMS Symptoms:

- Irritability

- Depression

- Lack of self-confidence

- Poor self-esteem

- Cravings

- Mood swings

- Bloating (fluid retention)

- Fatigue/lethargy

- Difficulty concentrating

- Tender breasts

- Confusion/fogginess

- Diminished motivation

- Headache

- Nausea

- Joint/ Muscle PainCramping

- Low back pain

- Nausea

- Insomnia

- Anxiety

The good news is PMS symptoms should start to clear up once the period begins. However, multiple studies evaluating perception of physical performance among female athletes found that many still considered their performance decreased compared to other times in the cycle, and there may be significant evidence to support a subtle decline.4,6

There is even evidence to support possible increase in DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness) during this phase compared to other times of the month.5

The lower levels of estrogen and progesterone are linked to an increase the amount of muscle damage compared to when higher levels of both hormones at other times of the cycle.

On the bright side, no one can say it’s impossible to have the best training day ever during this phase. While many may not feel their best, they can still go into the gym and absolutely crush their project. Speaking openly about menstruation is still a bit taboo, so no one knows what has truely been accomplished by female athletes during their period. But if the athlete is feeling a little off, use this time for active recovery wherein they complete mobility exercises and light workouts. One meta-analysis found a significant reduction in PMS symptoms in females who exercised aerobically or performed yoga during this phase of their cycle.6 During menses is a great time for some self-care!

Table 1: Climbing Exercises for Late Luteal & Early Follicular Phases (PMS & Period):

| ARC Training (Aerobic Respiration and Capillarity Training) | Purpose: To increase capillary density in the forearms, which can improve local aerobic endurance climbing. Example protocol: Select a route or traverse several grades below max. Complete 10-20 minutes of continuous climbing on the wall 1-3x with 5 minute breaks between bouts. Goal: The forearms should feel a slight pump, but not so much that failure is reached. |

|---|---|

| Technique climbing: ⦁ Precision footwork ⦁ Quiet feet ⦁ Hover drill |

2-3 grades below onsite. Climbing should be easy enough that control is maintained. |

| Minimum Hang board | 7 seconds on: 3 seconds off x 6 (total of 60 seconds) repeat for 6 sets. Rest for 2-3 minutes between sets. 30-40% of max or 2-4/10 perceived difficulty (RPE) |

| Mobility Work/ Joint Hygiene | Is,Ts,Ys, Open book, Hip 90/90s, Nerve glides, etc. |

Period & PMS Climbing Exercises:

Late Follicular, Ovulation & Early Luteal Phases

Once the period has wrapped up, hormone levels (specifically estrogen) begin to rise. Energy and overall mood should increase making the end of the follicular phase a great time to bear down on heavier training.7

Interestingly, ligamentous laxity peaks around ovulation and the beginning of the luteal phase. There is some evidence to suggest increased incidence of ACL tears during this phase.8 If the ACL is demonstrating laxity, then the other ligaments and tendons of the body likely are as well. During the ovulatory phase and early luteal phase give extra love to the fingers and joints, such as self-massage, skin care, or minimum hangs. The increased laxity may be something to be aware of but again, the evidence is not well supported and still being researched.

Repeatedly, the studies come back saying a highly individualized approach is the best way to handle menstrual cycle and training. Below is a table with example drills and suggestions.

Table 2: Climbing Exercises for Late Follicular, Ovulation & Early Luteal Phases:

| Project Climbing | Redpoint climbing or hard onsight climbing |

|---|---|

| Climbing Trip | Classics, fun moderates, hard projecting, enjoy the outdoors without the mess |

| Endurance | 4x4s: Choose 4 routes below onsight and climb four times in a row w/ 5–10-minute rests in between sets Circuits: Choose 3 – 4 routes, climb up and down the routes w/ 5-10 minutes rests in between. |

| Strength | Lifting – 3 sets x 8-10 reps squats, deadlifts, bent over rows, etc. Heavy hangboarding – Max. hang or strength based protocol |

| Power | Campus board training – feet on “lunging” 2-3 rungs above base rung for 6-8 reps per arm alternating. Can increase difficulty as needed. Training board- Tension, Moon, Grasshopper, etc., Dynamic movement training – Add speed to movements on the wall by selecting a route that is 1-3 grades below your max. |

To track the cycle there are a myriad of health and fitness apps that allow documentation of length of periods and symptoms. As the apps accumulate data, they can predict ovulation time frames as well as future periods. This data can be used to plan workouts according to what is needed. For example, if over the past several months the beginning of the cycle is characterized by low energy and cramps, consider exercises in Table 1. Conversely, if there is good energy and stoke, consider exercises from Table 2.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, a menstrual cycle is as unique to a female as their fingerprints. Recently, there has been an influx in menstrual cycle studies, but due to poor quality evidence, it is difficult to make any definitive recommendations. Historically, there has been limited female representation in research, and research on males has also been extrapolated to include females.9

That’s crazy, right?! Further research is needed to look at the correlation of menstrual cycles, possibly using hormone tracking technology, and climbing performance for females. Ultimately, athletes know their bodies best. Tracking their cycle and listening to their body will give them all the tools needed to make the most out of their climbing performance!

About The Author

Kaitlyn Detlefsen is a second year DPT student at Eastern Washington University. School keeps her busy, but in her free time she enjoys climbing in Spokane and surrounding areas. She also loves reading, spending quality time with friends, and visiting home/climbing in Colorado.

Disclosure Statement

The information provided here is for educational purposes and is not medical advice. Please schedule an appointment with a licensed physical therapist or your primary care physician for more guidance and specific recommendations.

References:

- Reed BG, Carr BR. The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. [Updated 2018 Aug 5]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/

- Najmabadi S, Schliep KC, Simonsen SE, Porucznik CA, Egger MJ, Stanford JB. Menstrual bleeding, cycle length, and follicular and luteal phase lengths in women without known subfertility: A pooled analysis of three cohorts. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020 May;34(3):318-327. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12644. Epub 2020 Feb 27. PMID: 32104920; PMCID: PMC8495765.

- Dilbaz B, Aksan A. Premenstrual syndrome, a common but underrated entity: review of the clinical literature. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2021 May 28;22(2):139-148. doi: 10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2021.2020.0133. Epub 2021 Mar 5. PMID: 33663193; PMCID: PMC8187976.

- Carmichael MA, Thomson RL, Moran LJ, Wycherley TP. The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb 9;18(4):1667. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041667. PMID: 33572406; PMCID: PMC7916245.

- Romero-Parra N, Cupeiro R, Alfaro-Magallanes VM, Rael B, Rubio-Arias JÁ, Peinado AB, Benito PJ; IronFEMME Study Group. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage During the Menstrual Cycle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2021 Feb 1;35(2):549-561. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003878. PMID: 33201156.

- Pearce E, Jolly K, Jones LL, Matthewman G, Zanganeh M, Daley A. Exercise for premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BJGP Open. 2020 Aug 25;4(3):bjgpopen20X101032. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101032. PMID: 32522750; PMCID: PMC7465566.

- McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E, Swinton PA, Ansdell P, Goodall S, Thomas K, Hicks KM. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020 Oct;50(10):1813-1827. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3. PMID: 32661839; PMCID: PMC7497427.

- Herzberg SD, Motu’apuaka ML, Lambert W, Fu R, Brady J, Guise JM. The Effect of Menstrual Cycle and Contraceptives on ACL Injuries and Laxity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Jul 21;5(7):2325967117718781. doi: 10.1177/2325967117718781. PMID: 28795075; PMCID: PMC5524267.

- Costello, J.T.; Bieuzen, F.; Bleakley, C.M. Where are all the female participants in Sports and Exercise Medicine research?Eur. J.Sport Sci.2014,14, 847–851.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.