Are Youth Climbers Aware of Injuries

Kids are not just small adults. Their bodies differ in anatomy, psychology, and skeletal maturity. Due to these differences, it is essential to understand youth athletes’ perceptions on injury and safe training practices in order to reduce the incidence of injuries. Little research has examined youth athletes’ perceptions to date, which lead our research team to conduct a study examining the awareness and knowledge of youth-specific climbing injuries and safe training practices from the perspective of adolescent climbers. We surveyed 267 elite, youth climbers (between the ages of 8-18), who were competing in the 2017 USA Climbing Youth National Championships.

How are adult climbing injuries different than youth climbing injuries?

Adult Climbing Injury

Unlike kids, the most common adult climbing injury is the A2 pulley injury, which is rare in youth climbers. An injury to the A2 pulley is discussed more often in the climbing community, and had been researched for almost ten years prior to when the first report came out on finger growth plate injuries in youth climbers. Additionally, A2 pulley ruptures have a distinct “popping” sound unlike growth plate injuries.

Youth Climbing Injury

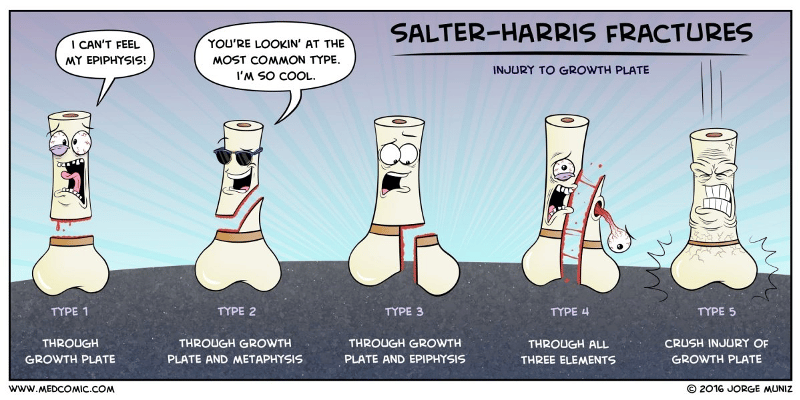

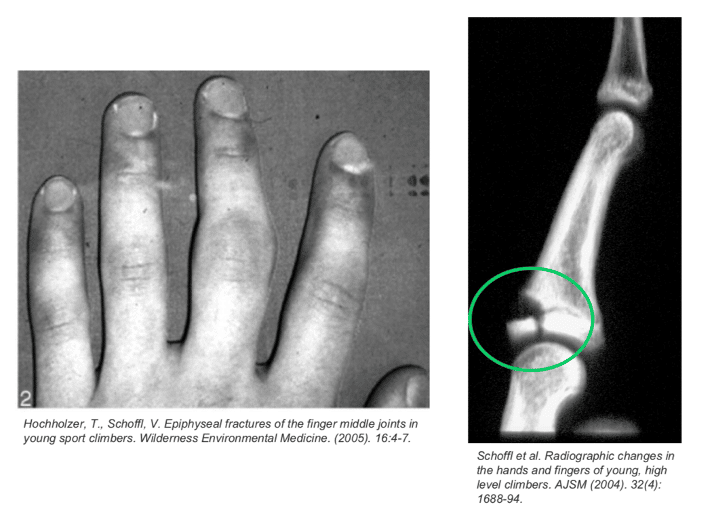

The most common youth climbing injury is an epiphyseal fracture to the finger, also known as a growth plate injury to the finger. These injuries most often occur around puberty. Unlike adults, growth plates are 2-5x weaker than the surrounding connective tissue, which leads to the growth plate being the most vulnerable site for injury in a skeletally immature athlete. The majority of these growth plate injuries in youth climbers (95%) are classified as Salter-Harris type 3 fractures. As shown in the picture below, a type 3 Salter-Harris fracture is when the fracture travels through the growth plate and the epiphysis (the end of the long bone).

How do finger growth plate injuries present?

- Gradual onset of pain in the finger with climbing

- No trauma or specific event involved (majority are due to overuse)

- Pain is located on the back side of the knuckle of the finger

- Long finger most affected

- Range of motion of finger limited

- IMPORTANT to get treated because if left untreated or if just climbing through the pain may result in:

- Growth arrest

- Growth arrest is when the growth plate in the bone closes prematurely. This can lead to one bone shorter than the other.

- Decreased range of motion

- Decreased range of motion is limited movement of the finger bending and straightening

- Long-term and angular deformity

- When the growth plate closes prematurely, the bone may be rotated. It is important to get these fractures treated, because if left untreated, the finger may not appear straight.

- Growth arrest

What are the known risk factors in the literature?

Previous known risk factors for finger growth plate injuries in youth climbers have been found to be 1) double dyno campusing and 2) excess use of the crimp grip. According to the British Mountain Council, adolescent climbers younger than 18 should avoid double dyno campusing. There has also been mention that hanging with the use of additional weights (i.e. a weight vest or weight hanging from the child’s harness) may be harmful for growth plate injuries. We also examined if the speed wall is associated with finger growth plate injuries in youth climbers… so stay tuned for the answer in the future once published.

So, what did we find in our study?

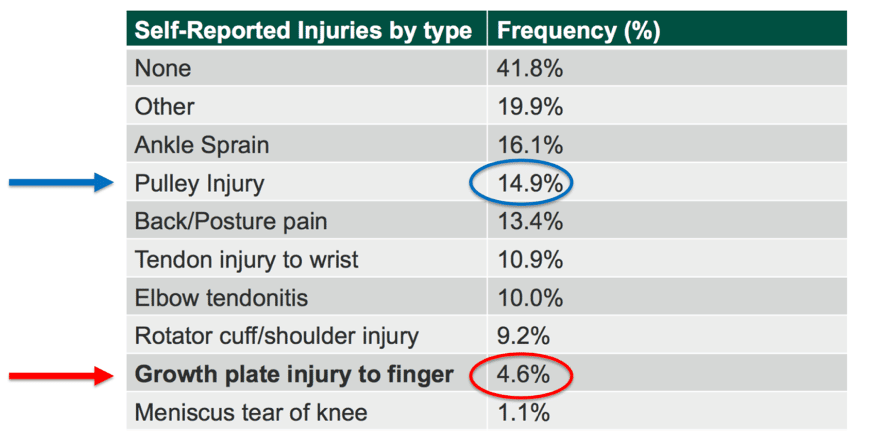

A. Self-reported Injuries

Out of all of our athletes, only 4.6% reported that they had suffered a previous growth plate injury to the finger, which was answered as the second least common answer. However, the pulley injury was answered 3x (14.9%) that as the growth plate injury to the finger. This may sound surprising to you since growth plate injuries are common and A2 pully injuries are rare in kids, right?

Well, although our findings were not in agreement with previous literature that reported the growth plate injury to the finger to be the most common youth climbing injury, we actually suspected more athletes to have reported a pulley injury due to the lack of awareness on growth plate injuries in youth climbers. Although pulley injuries are rare in youth, this injury tends to be much more commonly addressed and discussed within the climbing community. Additionally, 82% of athletes in our study who reported they had a pulley injury were uninformed about growth plate injuries to the finger, and may just have thought they had a pulley injury instead. We suspect that some of the youth athletes in our study could have been misdiagnosed, either by a medical professional or self-diagnoses, who are unfamiliar with youth climbing injuries.

Previous research also suggests that many finger growth plate injuries in elite, youth climbers may go unreported, especially among those who climb grades identical to elite, adult climbers. Educating athletes, coaches, parents, and medical professionals about the prevalence of finger growth plate injuries and the scarcity of A2 pulley injuries in youth climbers could increase diagnostic accuracy, improve care, and reduce long-term complications.

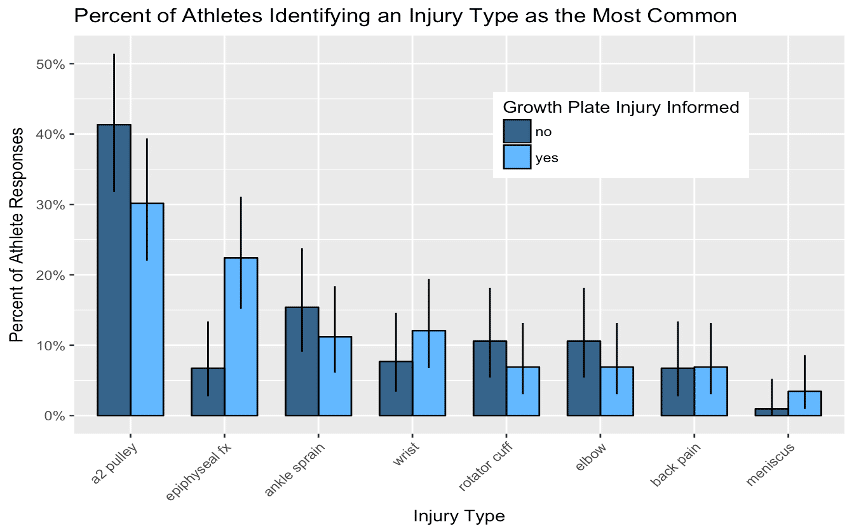

B. Injury Ranking Questions

We asked our youth climbers to rank on a scale of 1-8 (1 being most common, 8 being least common), what they believed is the most common youth climbing injury. The A2 pulley injury was ranked as the most common, while the epiphyseal fracture / finger growth plate injury was ranked as the second most common. However, the light blue bars in our figure below represent our athletes who answered that they were informed about finger growth plate injuries. Yet, many of those athletes still ranked the A2 pulley injury as the most common youth climbing injury.

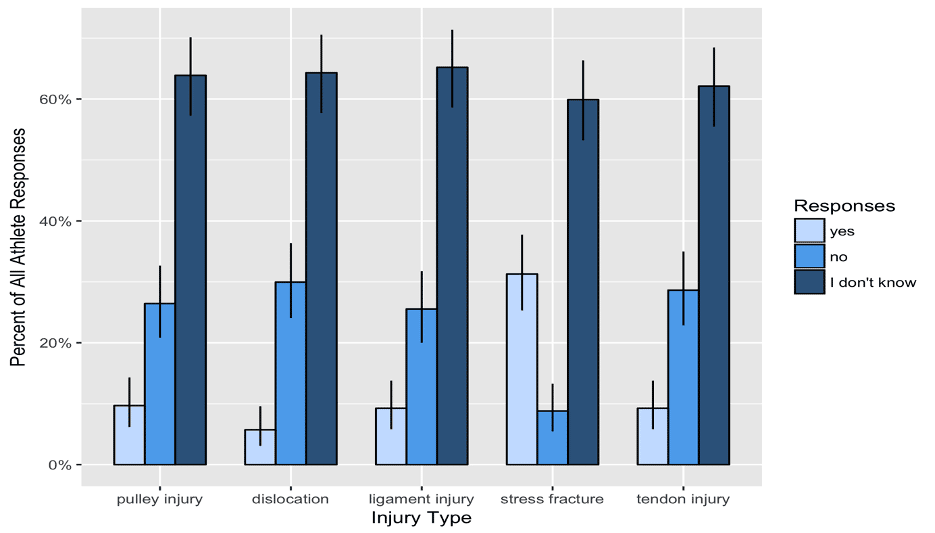

C. Kids’ Definition of Growth Plate Injury

We asked the youth climbers to further define what they believe is a growth plate injury to the finger. They could choose “yes”, “no”, or “I don’t know” answer options for each of the following injury types: pulley injury, dislocation, ligament injury, stress fracture, tendon injury. Stress fracture is the only correct answer option. For this figure below, if you look at the dark blue bars, those represent the athletes who answered “I don’t know” which represent the vast majority of the youth climbers in our study. Roughly 74% of youth climbers believed a finger growth plate injury was a type of pulley injury or did not know that it was not. It is crucial to educate our climbing community on the most common youth climbing injury and to make sure our kids understand these injuries.

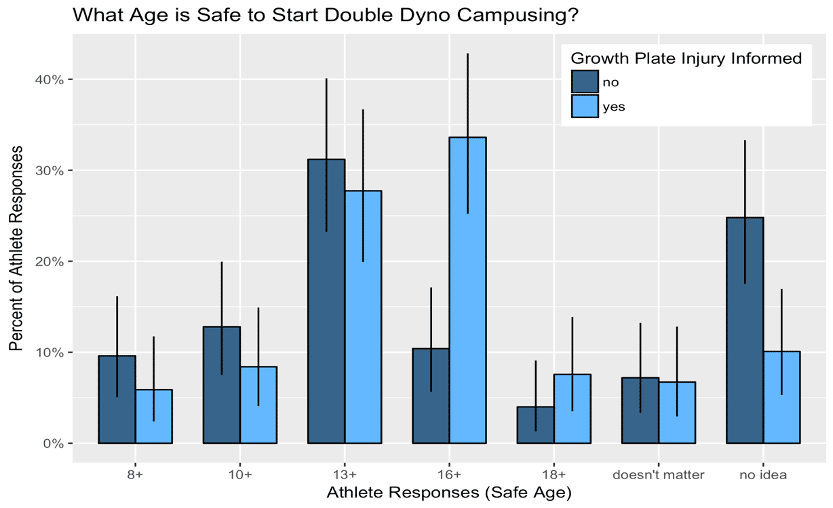

D. Safe Training Practices

Not only did we find the majority of our youth climbers to be unaware of youth climbing injuries, but we also found that many were unaware of the safe age to start double dyno campus boarding. In our study, only 5.7% answered with the correct age of 18+. The majority of our athletes answered that the safe age is 13+, which is the most vulnerable time for these growth plate injuries to occur.

Conclusion

The authors are NOT trying to discourage youth athletes from climbing. Climbing provides so many mental and physical benefits that largely outweigh the risks for injury. With climbing growing as a youth sport and entering the 2020 Olympics, MORE education is needed to hopefully reduce these injuries in youth climbers and keep our athletes safe and KEEP them climbing!

So more education and awareness is needed…what can we do?

We recommend that climbing gyms put signs up next to the campus board indicating the safe age to start double dyno campus boarding. Additionally, coaches and physicians should be aware of the warning signs of a finger growth plate injury along with its known risk factors.

Another suggestion to gain awareness is to require educational videos or online training for coaches regarding the signs and risk factors for a finger growth plate injury prior to the competition season.

We have also created a rock climbing injury tip sheet on the STOP (Sports Trauma and Overuse Prevention) Sports Injuries website. Information on growth plate injuries, among other injuries, are listed on the tip sheet. A downloadable link to the tip sheet is below:

Lastly, we created a return to climb protocol specifically on finger growth plate injuries in youth climbers geared for coaches and medical professionals. This is currently under review with a journal, and is planned to be published in November 2020.

Ongoing projects

We are currently looking at the association of finger growth plate injuries and the IFSC speed wall (stay tuned). Additionally, we are currently looking at early sport specialization in youth climbers (ages 8-18).

If any youth climber between the ages of 8-18 would like to participate in our study, please fill out the survey link here: https://redcap.tsrh.org/surveys/index.php?s=DKFRKL8ADN

*If you would like to read the full research article regarding this blog, here is the link: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/3/812

About the authors

Rachel Meyers, SPT

Rachel Meyers, SPT is a Doctor of Physical Therapy student at Duke University in Durham, NC. She is interested in pediatric sports medicine with a special interest in adventure and extreme sports injuries. She has been climbing for the past 13 years, and has been a sponsored climber with La Sportiva since the age of 15.

Aaron Provance, MD

Aaron Provance, MD is the Medical Director of the Sports Medicine Center at Children’s Hospital Colorado. His clinical interests are treating adventure and extreme sports injuries. He is also an avid ice climber.

For questions or more information, please contact: rachel.n.meyers@duke.edu

Twitter: @rmeyers95

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.

Great article and useful educational tools! I think it’s great that we continue to promote climbing and strength training with youth athletes! Having the ability to better monitor youth athletes with this information will give coaches and healthcare providers greater opportunity to modify training plans accordingly and further reduce the risk of injury. Great resource!