DIP Joint Pain

Joint pain is part of life as a rock climber, and so much emphasis is placed on finger pulley and flexor tendon injuries, but what about the other side of the finger? Our fingertips are our initial and primary link to the rock and the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) gets the brunt of the force, specifically the ring finger DIP (1).

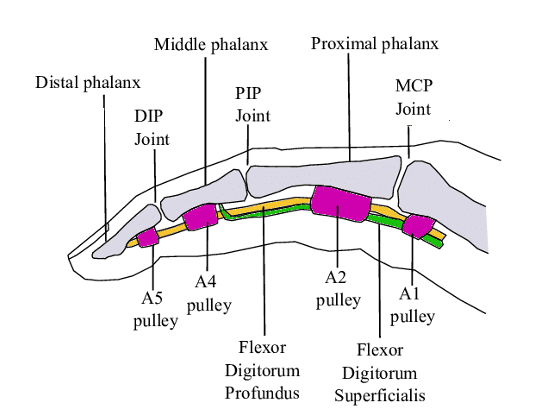

Before we dive into the mechanisms of and treatment for this injury let us orient ourselves with some basic anatomy of the fingers. Fingers are composed of many different bones, muscles, and ligaments that allow for a large amount of movement and dexterity. There are 2 types of bones in the finger itself, 3 phalanges (the distal, middle, and proximal) in the long fingers (2 in the thumb) , and 1 metacarpal bone composing the middle part of the hand. Surrounding these bones are numerous muscles, ligaments, tendons, and sheaths. The only muscles that are relevant for this article are the ones which flex the fingers, the Flexor Digitorum Superficialis (FDS) and Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP). Notice in the image below that it is only the FDP that crosses the DIP joint and attaches into that very last bone of the finger tip (2).

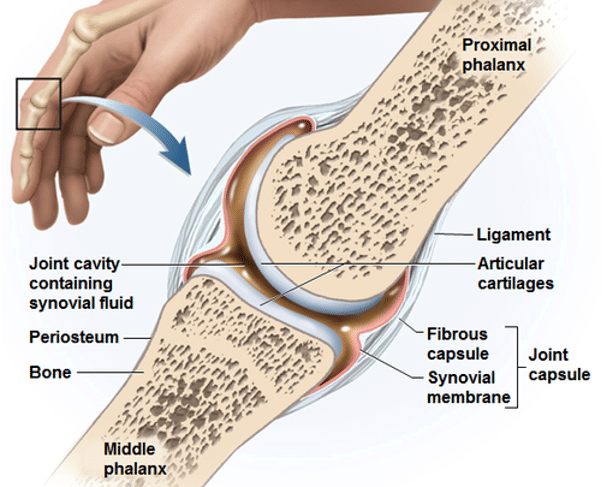

Each of the bones are linked together to create a synovial joint, with the DIP being your very first knuckle. The joint consists of a capsule that surrounds the articular surfaces, creating a cavity. This cavity is filled with synovial fluid, which acts as a lubricant as well as a medium for bringing nutrients to the cartilage covering the joint surfaces. The outer surface is referred to as the articular capsule, which holds the joint together, and the inner surface is referred to as the synovial membrane, or synovium, and this seals in the synovial fluid (2).

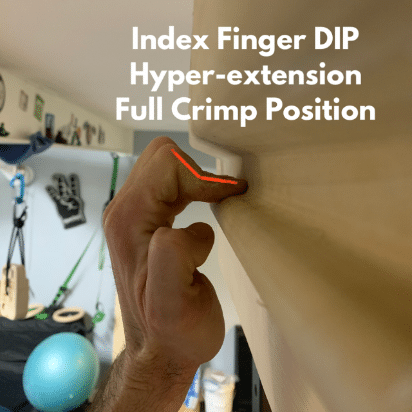

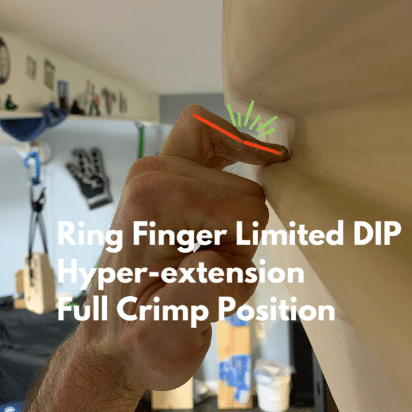

Synovitis (AKA Capsulitis) is a symptom of when the synovium of a joint becomes inflamed. In active, healthy persons, the most common cause of synovitis is overuse of the joint. Most exercises spread pressure over the whole cartilage surface, however, in rock climbing, the continuous gripping of holds, and more specifically using a Crimp Grip where the PIP joints are in hyper-flexion and the DIP joints are in hyper-extension, causes one specific spot of the cartilage to take a majority of the force. Over time this compresses the cartilage and reduces its ability to work as a shock absorber. Stresses to the synovium can also happen when fingers are twisted into tight places, such as with crack climbing. Micro-trauma occurs in the area, increasing the production of enzymes, which irritate the synovium. This actually increases the production of synovial fluid, which puts more pressure onto the synovium, causing it to thicken and increase the synovial fluid output even more, leading to chronic inflammation, joint thickening, osteoarthritis and bone spurs (1).

As stated, this is most prevalent in the PIP and DIP joints of the middle and ring finger in climbers, and presents as early morning stiffness, pain after stress of the area, decreased mobility and maybe swelling.

When we look at the DIP of the ring finger specifically, it has less hyper-extension mobility in general, and the top edges of the two bones jam into each other quite immediately when in a full crimp position, whereas the DIPs of the other fingers have a little bit of play to them. Over-reliance on a full crimp grip by newer climbers, progressing climbing intensity too quickly or climbers who are climbing at a higher level where frequent full crimp gripping is required, all have the potential for developing this injury.

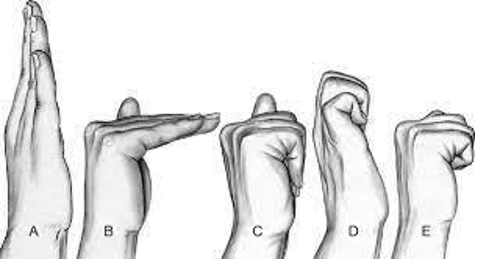

What is recommended in the acute phase is unloading the joint and treating with ice, rest, anti-inflammatories, massage for swelling and joint mobility work as pictured below (1)

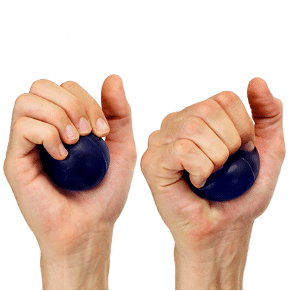

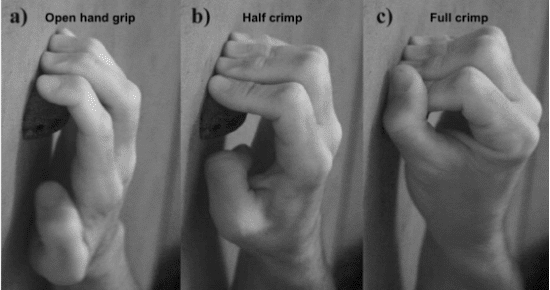

Long-term injury reduction and progression after the acute phase includes proper pre-climbing warm-ups, which include DYNAMIC stretching/mobility work (STATIC stretching has been shown to do nothing to warm you up or reduce injury risk) and progressive build-up of in-session intensity (3, 4, 5). Examples of a progressive dynamic warm-up for climbers can be finger tendon glides, ball squeezes using different grips, and hangboard repeaters at 30-40% of max using an open-handed or half crimp grip position (more on this below).

In regards to grip position, an open handed grip clearly unloads the DIP, however, it also more evenly distributes the work along both your FDS and FDP muscles. As you start moving into a more crimped position, the FDS will become dominant, pulling your PIP into more flexion, and once this occurs the FDP is not able to counteract the force of your whole body pulling your DIP into hyperextension (6).

Now, is it realistic to never train or climb in a crimp grip position? Absolutely not. We have to be prepared to use many types of grip positions depending on the steepness of the terrain and size/depth of the hold. However, if you are dealing with a finger joint injury, in order to initially unload the area and then gradually build up your tissues resiliency, you may want to think about using an open grip before progressing back up to training more severe hand positions.

What I would also recommend is assessing how much you use a crimp grip when you are climbing or hangboarding… is that grip really necessary or can you reduce the stress on your joints by using a half crimp or open-handed grip? If you find yourself full crimping no matter what modifications you make, maybe there is some other area of your body that needs some specific training.

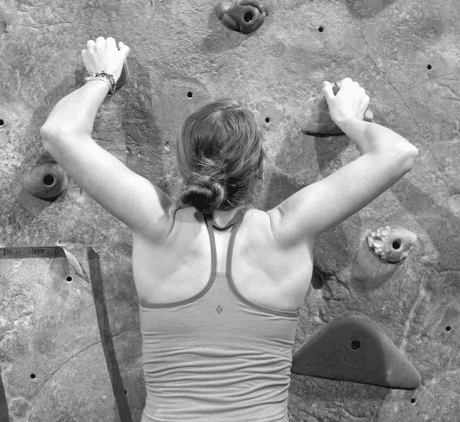

What some people don’t realize is that our grip is made stronger with wrist/finger extension. This is why when a climber starts to get tired or is gripping a hold that is at their max, they start to chicken wing, creating more wrist extension. This also moves your hand into an even more crimped position.

With this realization, concurrent with the finger flexor training that we all focus so much of our attention on, we want to strengthen our wrist/finger extensors to improve grip strength, grip position and joint stability. To make the right contractions possible, the whole muscle chain matters, and the strength of this chain is limited by its weakest link (6).

Extensor Exercises Which Can Help Strengthen and Stabilize Your Grip Include:

- Dumbbell Wrist Extensions: We are all familiar with these. This exercise loads your muscles isotonically. Keep your elbow flexed around 30-60 degrees and during the movement you only need to extend your wrist to slightly past neutral; 3-4 sets of 6-12 reps, can be done with a kettlebell or dumbbell.

- Pinch Grip Holds: A great way to isometrically load your extensors, and due to the open grip position, this has been found to load your extensors most effectively (6); High Intensity for 5-15 reps of 5 second holds, or Moderate Intensity for 5-10 reps of 15-30 second holds.

- Open-Hand Hangboard positions: Choose from any number of routines and strengthen your open-handed grip. As already stated, not only does this unload your injured DIP it distributes load through both flexor and extensor muscles more evenly.

Sometimes a full crimp grip is absolutely required during a climb, and climbers should not be afraid to use it or train this grip, however, making sure you’re not overusing it when it is not needed will decrease the frequency of stress to that joint.

References

- Schoeffl, V., Hochholzer, T., & Lightner, S. (2016). One move too many…: How to understand the injuries and overuse syndromes of rock climbing (pp. 64-65). Sharp End Publishing.

- II, A. F. D., & Agur, A. M. R. (n.d.). Upper Limb. In Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 13E. essay, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

- Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2013). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092538

- Small, K., Mc Naughton, L., & Matthews, M. (2008). A systematic review into the efficacy of static stretching as part of a warm-up for the prevention of exercise-related injury. Research in Sports Medicine, 16(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438620802310784

- Thacker, Stephen B., Gilchrist, Julie, Stroup, Donna F., & Kimsey, C. Dexter (2004). The impact of stretching on Sports Injury Risk: A systematic review of the literature. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(3), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000117134.83018.f7

- Gnecchi, S., & Moutet, F. (2015). Hand and finger injuries in rock climbers. Springer.

Author Bio

Steve Smith is a Doctor of Physical Therapy, who is a board certified specialist in Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, and Strength & Conditioning. He has been climbing since 2006, and has a particular interest in specialized sport training and rehabilitation, using science and evidence-based practice to improve performance and return patients to their highest level of athletic abilities. Steve works in an academic Orthopedic and Sports Medicine setting and, in his free time, acts as a training and injury risk reduction consultant to local competitive and recreational climbers. He currently lives in Huntington, WV with his wife and son.

Email: stephen.smith.dpt@gmail.com

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.