Clunk: Shoulder Instability Climbing

You hear it and feel it. Your shoulder popped in and out of the socket yet again. Going out and overhead to the next hold. Making contact with that jug at the end of the dyno. Pushing up and over the mantle. Reaching into the backseat of your car. Rolling over the wrong way in your sleep. Any and all of these positions may be vulnerable for the unstable shoulder.

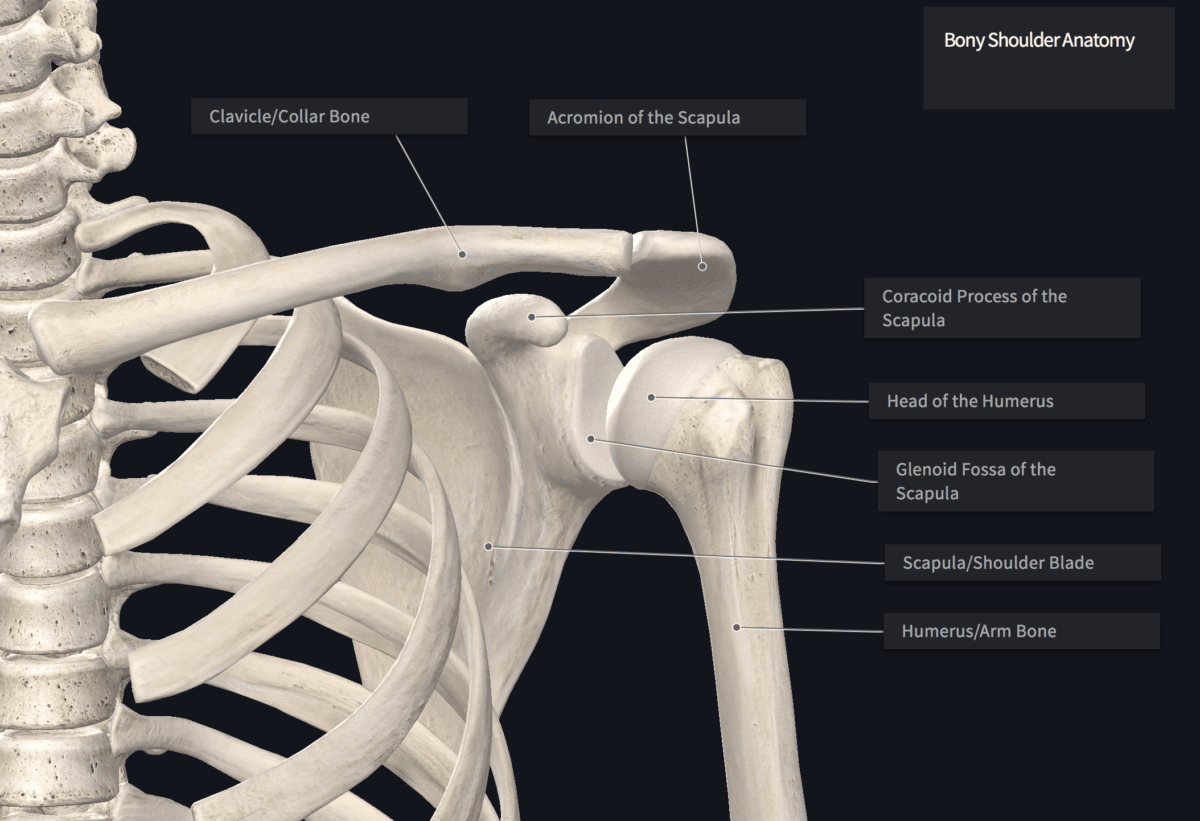

The shoulder is one of two ball-and-socket joints within the human body. This type of joint provides a wide range of motion. However, relative to the hip, the shoulder is less stable by design. The socket of the glenoid fossa on the scapula is quite small and shallow, while the head of the humerus is large. Below is an image from Complete Anatomy 2020 showing the bone anatomy of the shoulder.

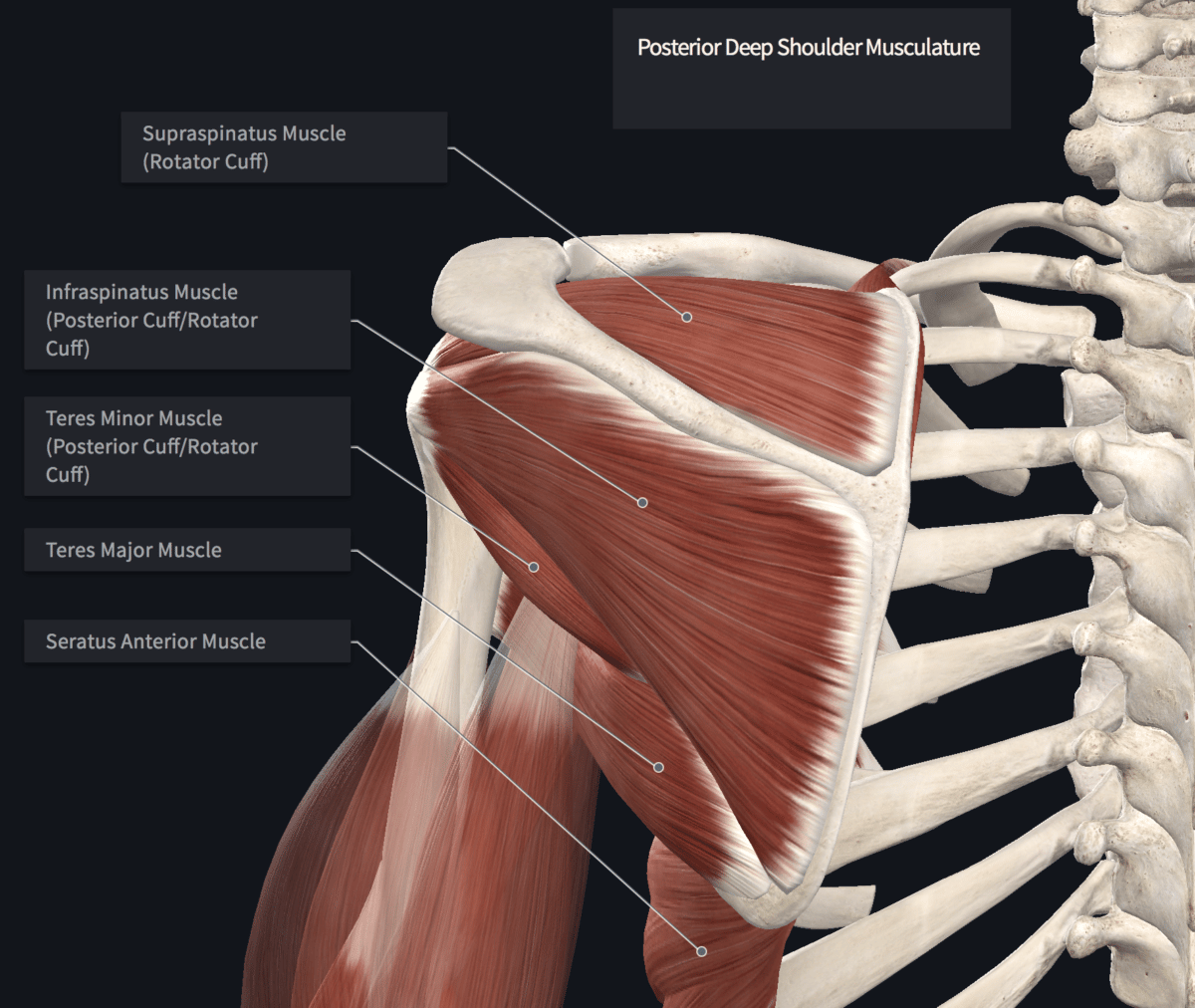

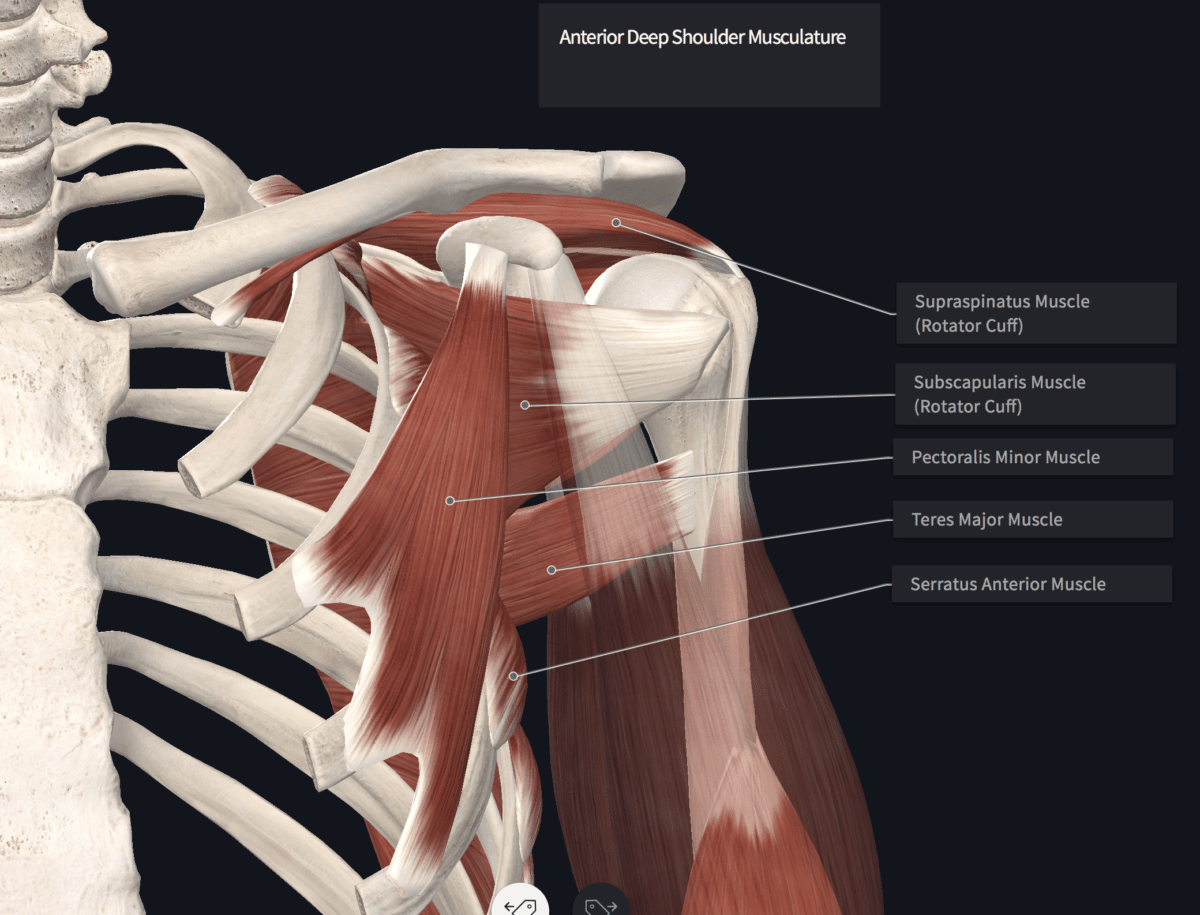

The design of the joint demands a lot of support from the static (i.e. ligaments, labrum) and dynamic stabilizing structures (i.e. muscles) to produce optimal arm posture and movement. Below are two images from Complete Anatomy 2020 showing the deep stabilizing structures of the shoulder and shoulder girdle.

Shoulder instability takes a variety of forms and poses a threat to the delicate balancing act performed by the joint’s soft tissues. Instability may occur via traumatic (i.e. fall, collision) or atraumatic (i.e. generalized laxity, repetitive overuse) mechanisms. A fall from a high ball onto an outstretched arm may be associated with a dislocation of the joint in which the humeral head comes out of the glenoid. Once the bones are returned to their rightful place, the person may still be at risk for recurrent dislocations or subluxation (partial or incomplete dislocation) with movement. Dislocation causes stress and injury to the surrounding muscles, ligaments, and the labrum. However, traumatic dislocation is not the only way these structures can be disrupted leading to instability. Repetitive overhead activity may also cause similar joint damage and instability. Pulling hard through an overhang and stabilizing against a gaston are just a couple examples of this type of activity for climbers.

There are multiple types of shoulder instability. They are named for the direction of abnormal displacement of the joint: anterior, posterior, inferior, and multidirectional.

- Anterior shoulder instability: The most common type of instability, especially if the mechanism of injury was traumatic. In this type of instability, the anterior-inferior portion of the joint capsule becomes very loose.

- Multidirectional instability: Does not typically have a specific event associated with it, but many have generalized laxity, or looser joints throughout their body; they may be described as “double jointed.” Multidirectional instability includes anterior, posterior, and inferior instability.

Pain, clicking, and unsteadiness coming from the shoulder may cause annoyance and trouble with daily activities. These feelings may be amplified for the climber as joint stresses at the shoulder during rock climbing are similar to or higher than those during gymnastic ring events. The shoulder is often part of the stable base from which movement can progress when scaling the wall. It is also is part of the chain that gives the climber a place to land when they move on to the next hold. Whether due to a traumatic fall or atraumatic overuse, instability in the shoulder can make completing your next project difficult. Left untreated, it may lead to further pain, continued joint degeneration, or increased risk of shoulder impingement syndromes and rotator cuff injuries.

For the purposes of this post, we will be focusing primarily on non-operative unstable shoulders. In the case of surgically stabilized shoulders, it is important to follow your physician’s protocol to best protect the repair as you recover and return to activity.

Signs and Symptoms

If you have any of the following, you may have shoulder instability.

- Physical deformity (changes at the shoulder joint that will be visible to the naked eye)

- Recurrent dislocations or subluxations

- Vague or deep shoulder pain

- Pain or apprehension with overhead activities

- Painful clicking or catching throughout arm movements

Assessment

The above signs and symptoms may be consistent with shoulder instability. This may be due to a fall on to the arm, a collision involving the shoulder, or repetitive, overhead overuse. In terms of the rock climber, overuse may be the more likely culprit. Projecting or pushing grades may lead to situations where you are practicing the same overhead reach over and over again, which puts repetitive high loads onto that unstable shoulder. For anterior instability in particular, the shoulder is most vulnerable in abducted and externally rotated positions; the lock-off position we commonly find ourselves in as climbers.

However, shoulder instability may lead to other problems at the shoulder and vice versa, especially in the event of a non-traumatic mechanism of injury. This would be marked by a more gradual onset of symptoms. In this case, it is important to go through a thorough physical evaluation to determine if an individual’s presentation truly lines up with the diagnosis of shoulder instability.

The physical examination will look at mobility, strength, and movement. People with unstable shoulders may find that they have full or even excessive shoulder elevation ranges of motion with pain at end ranges. However, it is common that the unstable shoulder will be limited in rotational ranges of motion. In terms of strength, it is typical to find weakness in the muscles that stabilize the scapula and external rotators of the shoulder. Finally, movement analysis may reveal dyscoordination among the muscles of the shoulder girdle. Most commonly seen is decreased upward rotation of the scapula when moving the arm overhead. This type of analysis may also indicate which muscles may be tight and possibly contributing to uncoordinated movement. If possible, it would be useful to see the climber climbing if a wall is available or through video. Depending on the severity, symptoms may not appear until the demands on the shoulder are increased, so some degree of climbing-specific analysis would be key to assessing a climber’s shoulder instability.

Special tests that will help differentiate shoulder instability from other shoulder pathologies include:

Apprehension & Relocation

This is a test where the examiner will bring the arm through rotational ranges of motion and feel for movement of the humeral head within the socket, as well as muscle guarding as the shoulder is brought closer and closer toward more vulnerable positions. A positive result for this test would be apprehension and excessive anterior translation of the humeral head and increased range of motion with added pressure at the humeral head at the point of muscle guarding.

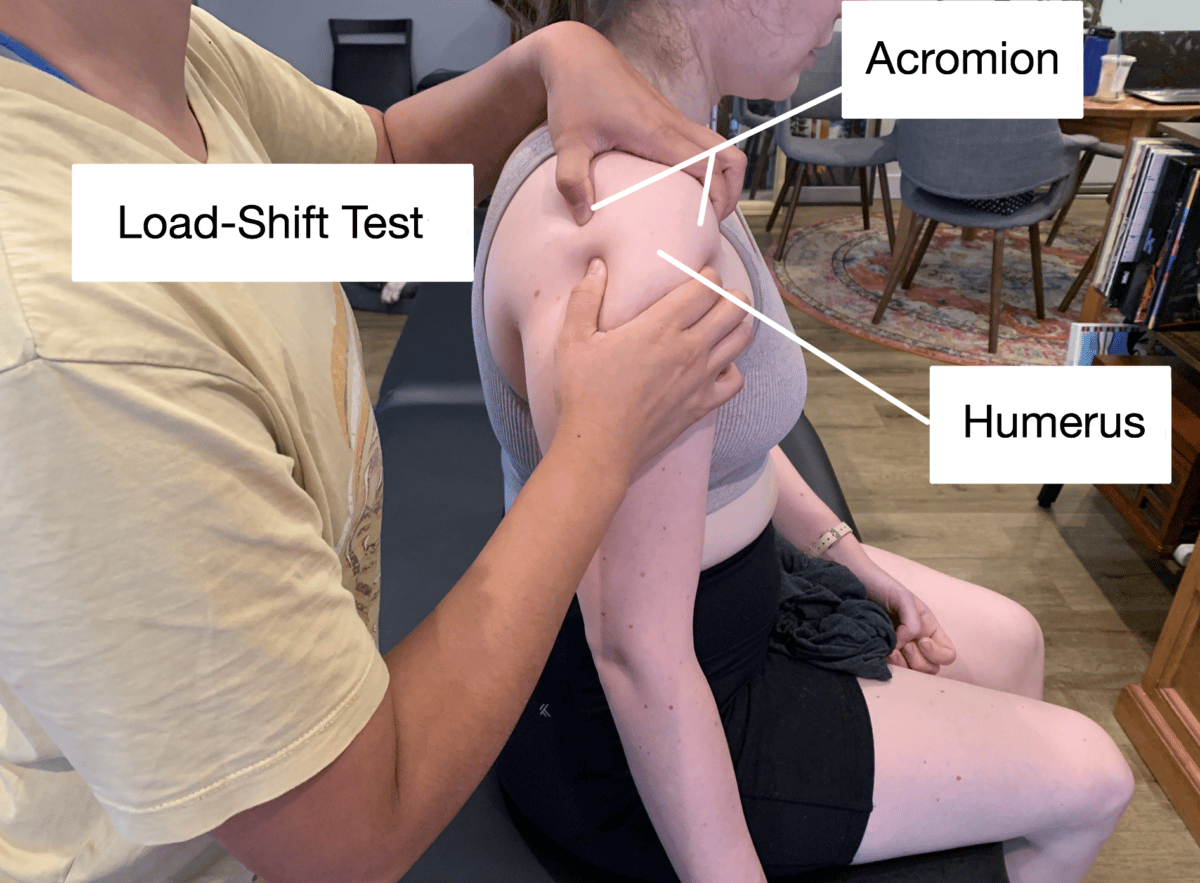

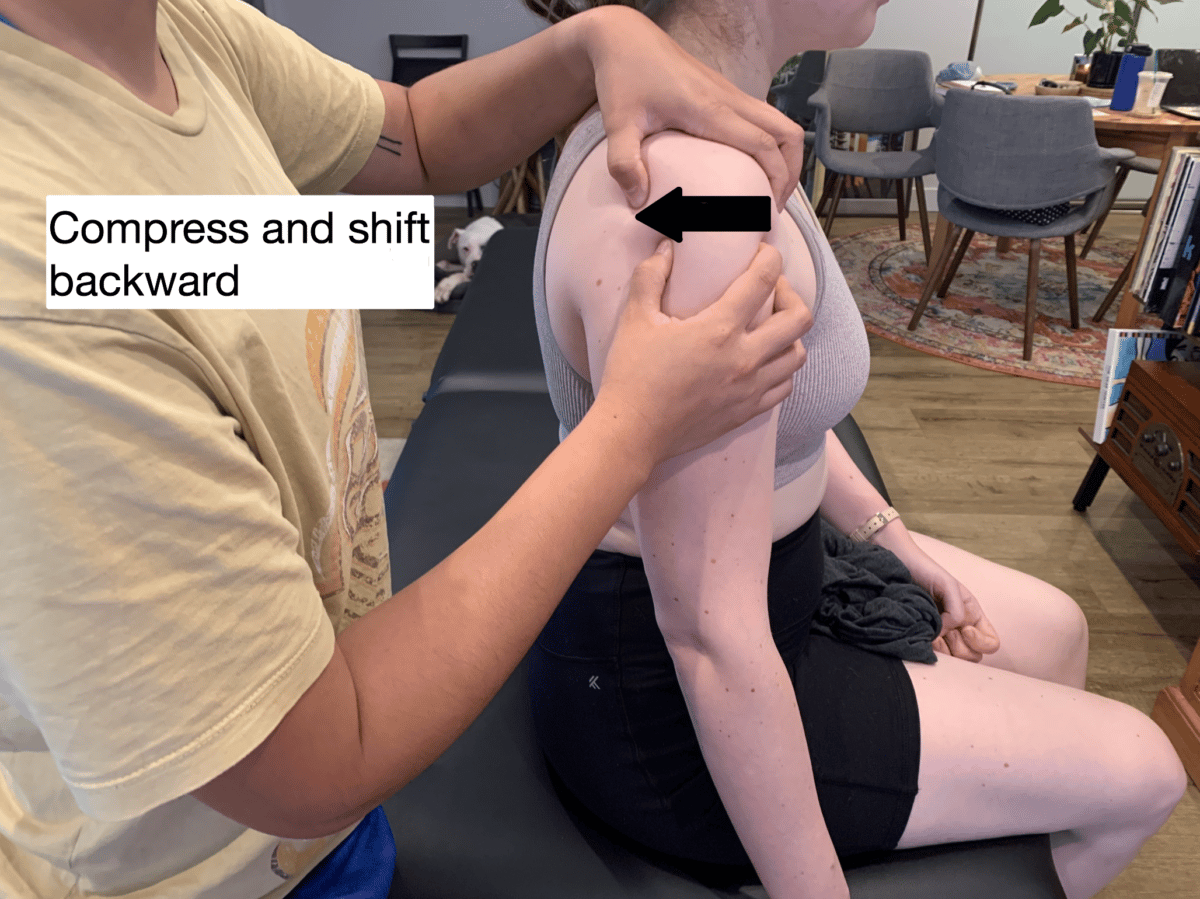

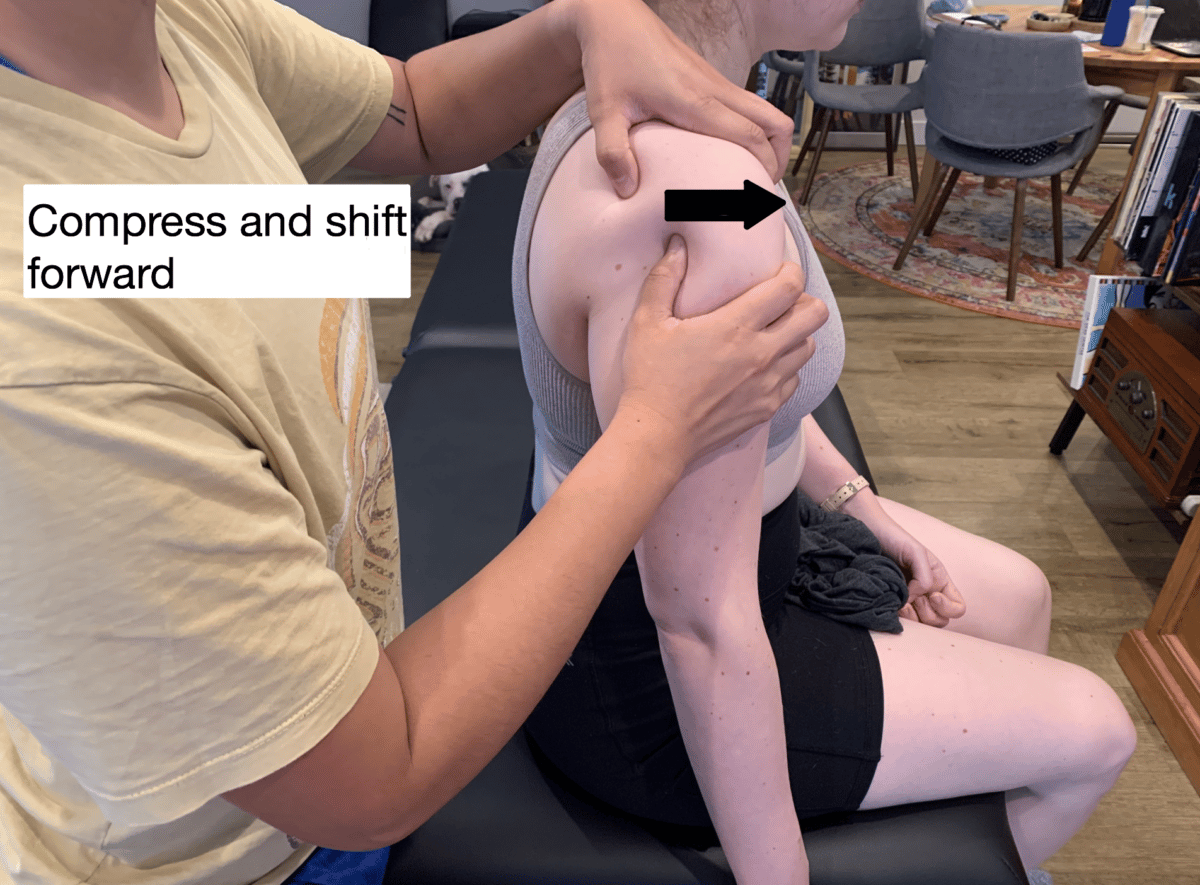

Load and Shift Test

This is a test where the examiner will stabilize the shoulder blade and compress the humeral head into the glenoid fossa and then translate it in anterior and posterior directions. They will then assess the amount of translation, end feel, and dislocation and relocation.

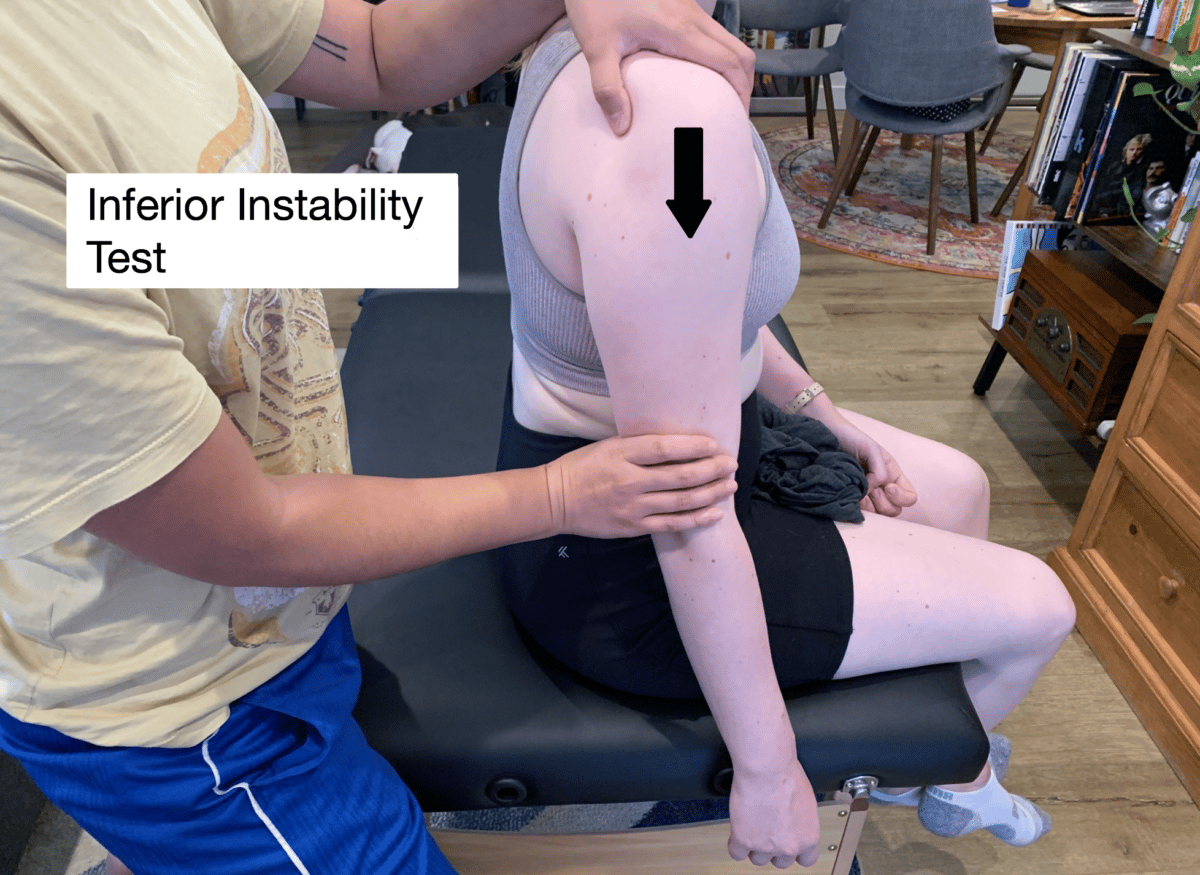

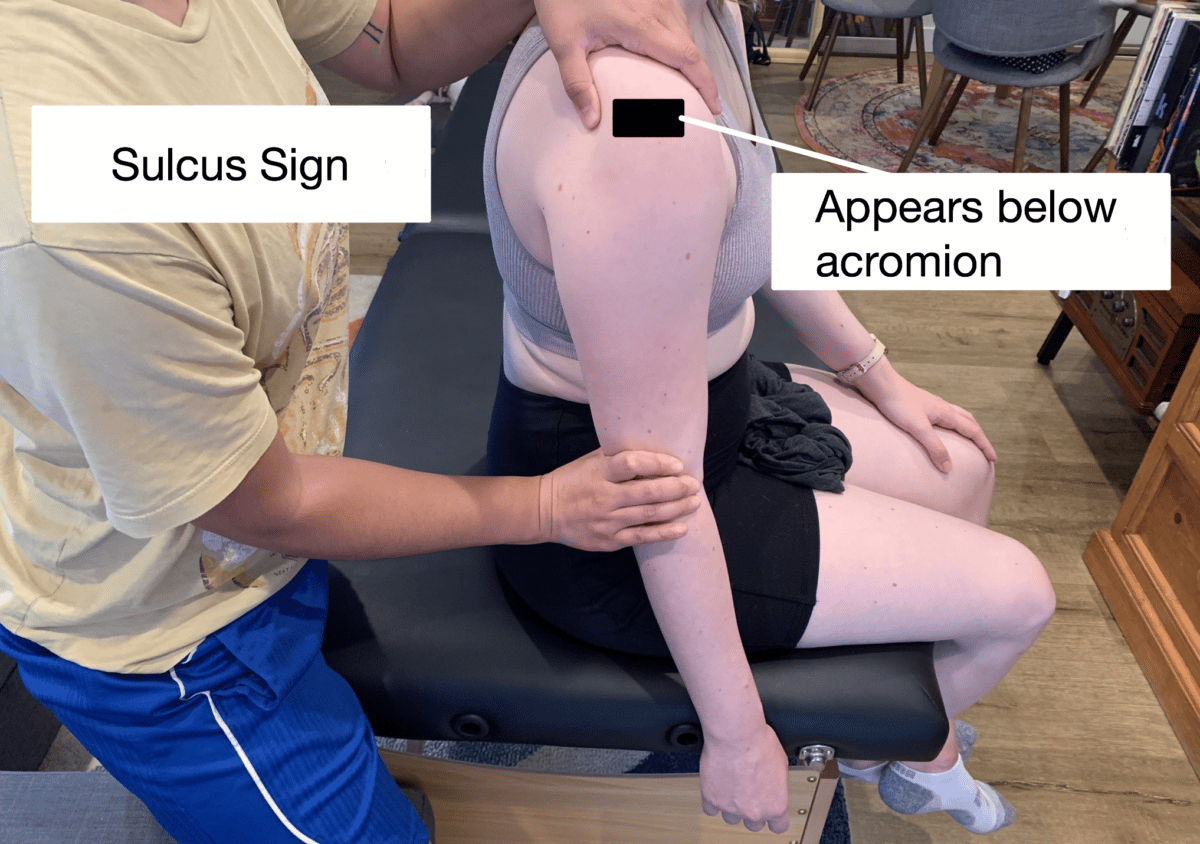

Inferior Stability Test

This is a test where the examiner will stabilize the shoulder blade and distract the humeral head from the glenoid fossa in a downward direction. A positive result for this test would be the appearance of a sulcus, or divet, at the shoulder joint.

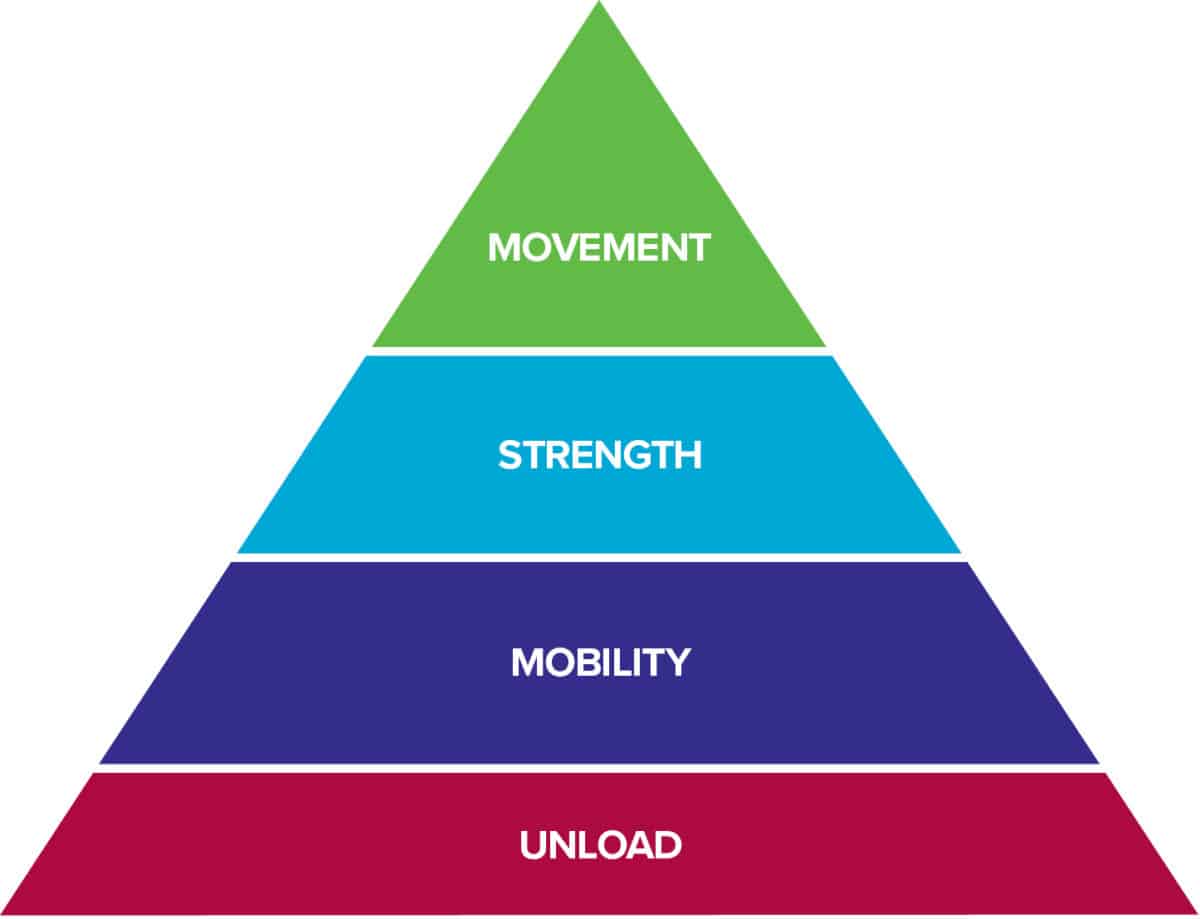

The Rock Rehab Pyramid

The physical examination and assessment should give you a good idea as to whether you have an unstable shoulder and in which directions it is most vulnerable. Now what? Dr. Jared Vagy developed the Rock Rehab Pyramid to help climbers who have sustained an injury return to crushing routes. The pyramid consists of four stages of rehabilitation that build upon each other as you make your way toward recovery. This format also provides guidelines upon which climbers can decide when to progress their rehabilitation program.

The bottom level of the pyramid aims to decrease Pain, Inflammation and Tissue Overload so that the tissues have the best healing environment. Often times, after an injury there is some sort of change in Mobility. After the tissues have calmed down from the previous level, this stage will look to reestablish normal, pain free range of motion. Once the injured area restores its mobility, it is time to increase the Strength of the surrounding muscles so that Movement in the following level can be coordinated and optimized. Click here to learn more about the rock rehab pyramid structure.

Rules for progressing through the Rock Rehab Pyramid are based on how the body is feeling the day after performing your rehab program:

- Increase in pain and soreness, regress one level

- No change in pain and soreness, maintain the same level for 1 week and progress the following week

- Decrease in pain and soreness, progress one level

This article will provide Rock Rehab Pyramid options for the climber with a shoulder with anterior instability because this is the most common type. Management of the various types of instability may have precautions and strategies that overlap and diverge based on the direction of instability and the unique clinical presentation of the individual. Due to this variability, the focus will remain on anterior shoulder instability.

Unload Exercises:

Sling

In the event of a traumatic dislocation, once the shoulder has been relocated it may be best to use a sling to allow for proper unloading of the shoulder so that pain, swelling, and inflammation can die down over the course of 3-4 weeks. The sling places the shoulder into flexion, adduction, and internal rotation, which is supported by a bent elbow. This is a relatively comfortable position for a painful shoulder.

Kinesiotape or Leuko Taping

Either after immobilization, or if there was no traumatic event, it may be helpful to use Kinesiotape or Leuko Tape to enforce better resting positioning and dynamic support of the shoulder and scapula during daily activities or exercise. Anterior shoulder instability may lead to rounded or forward shoulders as well as tightness of muscles such as pectoralis minor, which continue to pull the shoulder forward. This type of taping can take pressure off of these anterior structures by facilitating better activation of the scapular stabilizers on the back. These muscles are key to maintaining proper resting posture throughout the day and coordinated scapular movement when moving the arm.

Mobility Exercises:

Lacrosse Ball Soft Tissue Mobilization to Posterior Cuff Muscles

In shoulders with anterior instability, the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles, also known as the posterior cuff, become weak and stiff. Part of managing anterior instability includes managing the length-tension relationship of the posterior cuff. Length-tension is a concept that essentially states that each muscle has an optimal length at which it functions. The rotator cuff muscles are a key muscle group providing compression of the humeral head into the glenoid fossa. Disruption in the rotator cuff length or performance will affect these muscles ability to provide that stability at the joint, especially during movement. Shoulder dislocation and anterior instability will cause this disruption, and the first part of re-stabilizing will be to break up adhesions in the muscle and restore its pliability.

Sleeper Stretch

After adhesions in the posterior cuff have been broken up through soft tissue mobilization, the Sleeper Stretch provides an easy way to stretch the posterior cuff muscles while lying on your side. The surface below will stabilize the scapula so that the stretch will be most effective.

Posterior Cuff Cross-Body Stretch

The Cross-Body stretch is another way to stretch the posterior cuff. This should be performed standing up with some sort of doorway or post nearby. The shoulder blade should be tacked down by the doorframe as the arm is pulled straight across the body.

Strength Exercises:

Wall Slide with Loop

Anterior shoulder instability tends to cause problems with overhead movements, which are essential to climbing. The Wall Slide with a Loop trains the posterior cuff and scapular stabilizing muscles to promote proper shoulder blade movement and coordination.

Theraband Scapular Clocks

This exercise more closely mimics reaching out for the next hold. The resistance provided by the theraband requires the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff to keep the shoulder blade stable while the arm reaches. This will help train proper movement coordination of the arm with the shoulder blade.

Quadruped Reaches

In climbing, the shoulder does not only act to help lift the arm overhead, but also to provide a stable base of support while the other arm moves or you bring your leg up from a foothold. Performing reaching exercises in quadruped gives climbers to practice this type of stability on the ground.

Body Blade D2 Pattern

Scaling the wall sometimes demands that the shoulder move from a low hold to a high hold whether that is straight up, out to the side, or in a diagonal. The Body Blade D2 Pattern exercise with allow the climber to work on their motor coordination and dynamic stability through a large, diagonal range of motion.

90/90 External Rotation with Lunge

The abducted and externally rotated shoulder is a vulnerable shoulder in one with anterior instability. This is an important position for the rock climber, so it is important to train the shoulder in this position. The lunge may be a reverse, curtsey, or side lunge. This addition combines the upper and lower body positions we may find ourselves in on the wall.

Movement Exercises:

Dynos

For the unstable shoulder, dynos may be difficult to practice and perform. If possible, it may be easier on the shoulder to avoid these types of moves to decrease risk of falling on the shoulder and tractioning a loose shoulder high above the ground. However, there are some problems that will require you to dyno. In this case, it is important use your lower body to generate force and think about engaging the shoulder as you are making the leap so that there is more solid contact upon hitting that jug. Otherwise the muscles of the shoulder will have to work harder to catch you from falling if the muscles are not recruited until after you have made contact with the hold.

Mantles and Sitting with Arms Back

Mantles are already difficult and precarious for the healthy shoulder. It requires awkward maneuvers relying heavily on the arms to bring the lower body over a large obstacle. This increased demand on the shoulder with little help from the legs is stressful for the unstable shoulder. Especially when the arm is usually in positions of extreme abduction and rotation. These moves should be avoided when possible. Sitting with your arms behind you can compress the shoulder joint and stress the front of the shoulder capsule. When sitting after a climb, use your trunk muscles to support your weight instead of your shoulder.

Proper Lock-Off

When the unstable shoulder is the one stabilizing the next move, it is important to make sure the shoulder is fully engaged during the lock off. If the shoulder collapses it can push the head of the humerus closer to the loose and vulnerable anterior-inferior portion of the joint capsule. Engaging the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer muscles will help ensure a proper lock off so that this stable base remains so.

The Research

The research surrounding shoulder dislocation and instability has not yet made its way to working with climbing subjects. However, there is evidence surrounding this injury in terms of what types of changes occur at the joint after injury, as well as its management and rehabilitation. We can take the information and findings from this research and apply it to a climbing-specific population.

People who have anterior shoulder instability will present with changes in range of motion as well as muscle function. In 2014, Sadeghifar and colleagues investigated the difference in internal and external rotation range of motion and muscle strength between healthy shoulders and shoulders with recurrent anterior instability. They found that compared to healthy shoulders, the unstable shoulders showed decreased range of motion in both internal and external range of motion at a 90/90 position (shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and elbow bent to 90 degrees). In this same position, it was found that the unstable shoulders presented decreased strength of these same muscle groups. These changes are likely due to changes to the soft tissues surrounding the shoulder leading to mobility and strength deficits. The 90/90 position is particularly relevant for climbers, as this is a position we find ourselves in quite often as we are scaling the wall.

These changes in range of motion and muscle strength often lead to motor coordination deficits. This sub-optimal movement perpetuates the status quo that the injured tissue operates under. Barrett (2015) talks about this in a discussion of the assessment of nontraumatic shoulder instability. Possible causes for continued abnormal movement patterns in the unstable shoulder include weakness, pain, fear, and impaired proprioception. Barrett also states that there is decreased activity and reflex activity in the lower trapezius, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and deltoid muscles, while the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi muscles are overactive. These muscle weaknesses, imbalances, sensory impairments, and psychological factors can all contribute to poor coordination of overhead movements. Outside of onset of symptoms, it is important to look out for aberrant movements during movement analysis of the unstable shoulder. These may include: scapular downward rotation, anterior tilt, scapular winging, unnecessary trunk movements, and excessive internal rotation of the arm. These clues in the movement analysis may indicate which tissues may be limited, pain sources, or contributing to poor coordination.

In general, management the unstable shoulder includes several phases that will build upon one another. In this article we talked about Dr. Vagy’s Rock Rehab Pyramid. Both Hayes and colleagues (2002) and Lefevre-Colau and colleagues have outlined focused rehabilitation progressions for this condition. If there is a traumatic dislocation, they both recommend immobilization in a sling for 3-4 weeks. In general, activity with the injured shoulder should be scaled back for about 6 weeks. Early stages of rehabilitation focus on isometric contraction of the rotator cuff and surrounding shoulder muscles and restoring range of motion. This is followed by training of the scapular stabilizers, with a focus on restoring proper upward rotation via coordination of the upward rotation force couple of upper trapezius, serratus anterior, and lower trapezius. However, it is important to note that upper trapezius may be overactive, while the other two muscles may have reduced activity. In this scenario, upper trapezius may be working to elevate the shoulder blade, but without the help of the other two muscles, cannot adequately upwardly rotate on its own. Lack of balance between the three muscles ultimately leads to decreased upward rotation and sometimes neck pain and tension.

Throughout the rehab process it is important to be restoring flexibility to muscles such as upper trapezius, levator scapulae, pectoralis minor, and the posterior cuff. As muscles surrounding the shoulder blade begin to regain strength, it is appropriate to being retraining the rotator cuff muscles. It is then important to begin challenging dynamic stabilization of the scapular and rotator cuff muscles as the arm moves about in space. This is also when axial loading of the affected shoulder becomes appropriate. Finally, it is time to incorporate functional and sport-specific movements. This important so that the flexibility and strength training done in previous weeks may be translated to real life situations that are relevant to you. The Rock Rehab Pyramid provided in this article are climbing specific examples of this general progression supported by the research evidence. However, there are many more possibilities and exercises that would be helpful for the recovering shoulder.

See a Doctor of Physical Therapy

If you are looking for a way to navigate climbing despite your shoulder instability or any other musculoskeletal problem, considering seeing a Doctor of Physical Therapy. Physical therapists are movement specialists and are educated and equipped to help you come back from injury, prevent future recurrences, and optimize your climbing performance. If you are going through the Rock Rehab Pyramid provided in this article and you still are not seeing the results that you are looking for, it may be helpful to see a Doctor of Physical Therapy. They will be able to perform a full evaluation of your unique case, expand upon the exercises in this article, and continue to guide you on your road to recovery.

About the Author

Kirsten Hee is a second year Student Physical Therapist studying at Mount Saint Mary’s University in Los Angeles, California. Before she found rock climbing, she was a nationally ranked sabre fencer and Division III NCAA goalie for the Occidental College women’s lacrosse team. She first climbed outside of the birthday-party-setting while studying abroad in the United Kingdom. Since then she has been primarily bouldering at various local Los Angeles gyms, and getting outside when possible in places such as Stoney Point, Bishop, and Joshua Tree.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.