Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) Evaluation & Management for the Rock Climber

You’ve always been more flexible than those around you, maybe you grew up being referred to as “double-jointed”, you’ve got a mean hitch-hiker’s thumb, and most of those “difficult” yoga poses are actually fairly easy. As a rock climber you use this to your advantage by favoring high steps, full-crimping most hold types, and sitting into a frog legged squat is a go-to resting position. This is great on some routes that demand a flexy strategy but maybe you’ve noticed much more difficulty with other styles of climbing that require dynamic powerful moves or more stability in other grip types like pinching and half-crimping. Perhaps, you also experience occasional aches and pains around your joints throughout a climb session. Are these simply characteristics of being naturally flexible or are these possible signs of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)? Truthfully, it could be either so let’s dig a little deeper! Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome or EDS encompasses a group of heritable disorders which affect the body’s connective tissue such as the skin, ligaments, blood vessels, or other organs. I won’t bore you with the entire history of EDS, but to give you a decent general picture, it was first identified between 1901-1908 and in the 1960s a classification system was created which continues to expand as we learn more. Currently, there are six different major types and evolving literature describes classification of thirteen different subtypes within EDS. All types will have presence of joint hypermobility and other types may have additional issues affecting vascular tissue, skin, muscle tone, or even eye tissue.

Signs & Symptoms:

Common signs and symptoms include:

- Joint instability accompanied with pain, clicking, and/or popping: joints may feel unstable or loose leading to frequent joint pain, audible popping, and dislocations during movement due to lax ligaments.

- Soft tissue injuries: Frequent muscle / tissue aching, sprains, and strains may occur due to the added stress from excess laxity in connective tissue around the joint.

- Skin involvement: In addition to joint hypermobility some individuals also have stretchy or fragile skin that is prone to easy bruising, atrophic scarring, and delayed wound healing.

- Dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction): In some cases, individuals will also have some dysfunction within the autonomic nervous system which will specifically affect vasculature and heart valves often leading to symptoms like dizziness, fainting, and/or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

- Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement: Due to some abnormalities with tissue structure GI distress may also occur, manifesting as diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or other digestive issues.

As a climber, these signs and symptoms could become significant barriers to participating in and enjoying the sport. If you primarily sport climb, maybe frequent joint pain, shoulder dislocations, or grip stability have been cumbersome challenges. If you’re stoked on bouldering, you likely hesitate to tackle problems that demand dynamic movements or require you to fall instead of downclimb. As a trad climber, you might struggle with significant and chronic joint pain around the hands, ankles, and knees. In addition, regardless of your preferred style or setting, you may also encounter prolonged difficulties with gobies, fingertip splits, and dry skin.

Assessment:

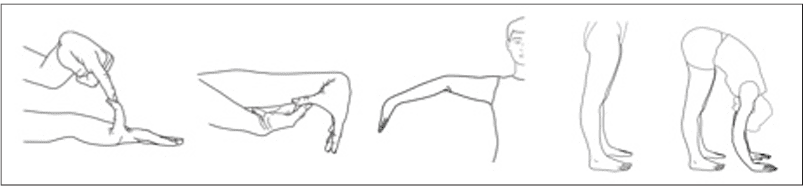

While many types of EDS can be confirmed with genetic testing, there has not been a genetic marker found for the most common form of EDS, hEDS or the hypermobile type, making this type reliant on clinical findings of identifiable signs and symptoms. A true diagnosis of EDS requires a comprehensive evaluation from a healthcare provider who is able to order genetic testing, gather pertinent health history information, and provide a Beighton hypermobility score. The Beighton hypermobility score is assessed on a 9-point scale by the following criteria:

- The 5th digit (pinky finger) bends back toward the top of the hand beyond 90°

- The 1st digit (thumb) can be bent enough to touch the forearm

- The elbow hyperextends (bends “backwards”) to an angle greater than 10°

- The knee hyperextends (bends “backwards”) to an angle greater than 10°

- When doing a forward bend, maintaining straight legs, the floor can be touched with flat hand

1 point is given for each section and each side, meaning if only one elbow hyperextends it is counted as one point for that section but two points are given if both elbows hyperextend and so on. Meeting the criteria for generalized hypermobility depends on an individual’s age. Pre-pubertal children or adolescents need a score ≥6, pubertal men and women up to age 50 need a score ≥5, and those over the age of 50 need a score ≥4. To be clear this aspect of assessment alone does not diagnose you with EDS. However, meeting or surpassing the generalized hypermobility scores described above may indicate a need for further evaluation, especially if you also experience several of the common signs and symptoms also described above such as frequent joint pain, dislocations, and/or stretchy skin. If you are simply just a flexible person, you may not fit into a hypermobile score range or you may qualify for hypermobility but have no other characteristics of EDS, potentially placing you in a different category of hypermobile conditions.

Training Strategies & Considerations

Whether you receive a diagnosis of hEDS or a general hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD), it may feel complicated to manage the unique challenges that arise with maintaining an active lifestyle and continue pursuing your passion of climbing. The good news is that research has shown that consistent exercise and strength training is actually one of the most beneficial things someone can do to manage hypermobility! However, it is important to approach exercise and training in a way that builds stability around the joints and reduces repetitive stress on the connective tissue. So, what are some management strategies to keep you climbing and injury free? This will vary depending on the severity of each individual’s hypermobility as well as the frequency and intensity of training practiced but some general strategies should include:

→ Focus on closed chain exercises.

If we think of the body as a chain linked together by the joints, the legs are linked together by the hips, knees, and ankle/foot and the arms are linked by the shoulder, elbow, and wrist/hand. Closed chain exercises are movements that require the ends of these chains, hand or foot, to be fixed on a surface such as a wall, table, chair, or the floor as opposed to open chain which allows the hand or foot to move freely in space throughout an exercise (i.e. bicep curl, bench press, seated knee extension). Examples of closed chain exercises include push-ups, pull-ups, rows, tricep dips, squats, and lunges.

Closed chain exercises are especially helpful for hypermobile joints because there is a compressive force through the joint chain that helps create more stability around the joints while strengthening the surrounding musculature and connective tissue. This added compression helps prevent excessive joint play that can put repetitive stress on connective tissue and lead to injury. This doesn’t mean individuals with hEDS should never perform open-chain exercises because open-chain exercises have benefits as well; however, when hypermobility is a concern it is recommended to build foundational strength with closed chain exercises and gradually progress to incorporating open-chain exercises. This approach helps condition control in your movements and reduce the risk of injury throughout a consistent training routine.

→ Build Endurance & Power.

Increasing endurance (even if you’re only interested in bouldering!) is essential for building up our resistance to fatigue. We want to be resistant to fatigue because we tend to get sloppy with our body mechanics and form as we get tired which often leads to injury. Building up our endurance also allows us to play longer! Training endurance can include high reps of low load resistance exercises, traversing around the gym, or ARC training.

Whether it’s your jam or your nemesis, training power is also essential for promoting resilient connective tissue. It’s always important to consider progression and amplitude when it comes to power training but this is especially true for those with hypermobile joints. The key with hEDS or HSD is to keep the majority of your power training within a manageable range of motion rather than repeatedly working into your max range or max extension.

→ Be Mindful of your Volume & Recovery.

It’s important to remember that building strength and adapting our bodies toward our specific sports takes time, which can be challenging to accept when the stoke is high and the gym is full of fresh new routes. Plus, there’s this pervasive mentality of no pain, no gain or how am I going to improve if I don’t push myself, right? The problem with these mindsets is they are just too general – not all pain is good or beneficial pain and “pushing” ourselves looks different for everyone. Muscle soreness is a natural part of physical training but that connective tissue we keep bringing up, doesn’t get sore or tired in the way our muscles do. This can make it all too easy to unknowingly put too much stress on these supportive joint structures when we overdo our volume or training intensity. So, even if you aren’t completely spent or dealing with much muscle soreness after a session, practice checking in with your body and pay attention to any twinges or tweaks that may come up before, during, or after climbing. When you notice a twinge here or tweak there, even if minor, this is a helpful indicator to scale back your volume and intensity a bit to be proactive about injury prevention and keep you climbing.

Prioritizing adequate recovery is an often forgotten piece of maximizing the benefits of your training. The recovery period is critical for healing and converting the stress of training into strength. So if you are someone who tends to push themselves to do more when falling short on reaching goals I encourage you to embrace getting the most out of your rest days. Ask yourself, How am I sleeping? How many hours am I getting, and how do I feel when I wake-up? What have my meals looked like, are they covering my nutritional needs? Am I eating enough to support my training load? How have I been managing my stress? Ensuring you are meeting these foundational needs is a simple, albeit still challenging in our busy lives, way to boost your recovery and get full-value out of all the work going into those active training days.

The strategies above are meant to help guide you toward building strength and stability and subsequently protect your joints and prevent injury. However, there is no specific protocol or program to follow because hEDS and/or HSD presents differently from person to person, making the specific approach to these general strategies highly individual. A skilled training progression is especially important when managing hypermobility, particularly in a sport like climbing where we are often “hanging” in our joints to rest on route and utilizing our flexibility to reach holds or execute a crux move. Whether you are new to climbing and just discovering your hEDS/HSD or a seasoned climber who has been managing their hypermobility for some time, consulting with a physical therapist (PT) can help you safely execute these strategies and collaborate with you on creating personalized exercise that both target your unique hypermobile challenges and your individual weaknesses while keeping you safe from injury. Forming a relationship with a PT is not only great for having professional support around tweaks and rehab but it’s also a wonderful way to gain more knowledge and insight around your specific needs as you hone in an independent training approach. Lastly, keep climbing and moving! Finding out you have hEDS/HSD or having previous injuries credited to this condition by health care providers may influence you to become hesitant or overly cautious around exercise and dynamic movements but the more we avoid certain activities and movements the more difficult it is to adapt to them. Exposing ourselves to a variety of climbing styles, hold types, and movements is the best way to adapt and improve. Utilize mindful discretion, modify as needed, and climb on!

Author Bio:

Amber Wagner-Haston is a PT student and climber from Tucson, AZ. Currently, she resides in Flagstaff, AZ, with her husband, where she is completing her DPT degree at Northern Arizona University (NAU). Amber believes that movement is the best medicine and has special interest in working with climbers, hypermobility, and trauma recovery. In their spare time, Amber and her husband, Kurt, enjoy getting outside together whether it be climbing, exploring the Grand Canyon, cold plunging, or running retrieve missions after Kurt’s paragliding adventures.

Resources:

- Buryk-Iggers, S., Mittal, N., Santa Mina, D., Adams, S. C., Englesakis, M., Rachinsky, M., Lopez-Hernandez, L., Hussey, L., McGillis, L., McLean, L., Laflamme, C., Rozenberg, D., & Clarke, H. (2022). Exercise and Rehabilitation in People With Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Archives of rehabilitation research and clinical translation, 4(2), 100189. https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.1016/j.arrct.2022.100189

- Liaghat, B., Skou, S.T., Søndergaard, J. et al. (2020). A randomised controlled trial of heavy shoulder strengthening exercise in patients with hypermobility spectrum disorder or hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and long-lasting shoulder complaints: study protocol for the Shoulder-MOBILEX study. BioMed central, Trials, 21(992). https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.1186/s13063-020-04892-0

- Malfait, F., Francomano, C., Byers, P., Belmont, J., Berglund, B., Black, J., Bloom, L., Bowen, J. M., Brady, A. F., Burrows, N. P., Castori, M., Cohen, H., Colombi, M., Demirdas, S., De Backer, J., De Paepe, A., Fournel-Gigleux, S., Frank, M., Ghali, N., Giunta, C., … Tinkle, B. (2017). The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics, 175(1), 8–26. https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.1002/ajmg.c.31552

- Parapia, L., & Jackson, C. (2008). Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A historical review. British journal of hematology, 141(1), 32–35. https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.06994.x

- Physiopedia. (2024). Beighton Score. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score

- Reychler, G., De Backer, M., Piraux, E., Poncin, W., & Caty, G. (2021). Physical therapy treatment of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: A systematic review. American journal of medical genetics. Part A, 185(10), 2986–2994. https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.1002/ajmg.a.62393

- Ritelli, M., & Colombi, M. (2020). Molecular Genetics and Pathogenesis of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Related Connective Tissue Disorders. Genes, 11(5), 547. https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.3390/genes11050547

- Tinkle, B., Castori, M., Berglund, B., Cohen, H., Grahame, R., Kazkaz, H., & Levy, H. (2017). Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (a.k.a. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Type III and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type): Clinical description and natural history. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics, 175(1), 48–69. https://doi-org.libproxy.nau.edu/10.1002/ajmg.c.31538

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (2024). Assessing joint hypermobility. https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/assessing-joint-hypermobility/

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (2024). EDS types. https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/eds-types/

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.