Shoulder Health for Adaptive Climbers with Spinal Cord Injury

Whether you’re an experienced climber or just getting into the sport, protecting your shoulders is vital for your long-term mobility, activities of daily living, and enjoying climbing! Combine a love of climbing with a spinal cord injury (SCI) and it is truly imperative to have a strong shoulder maintenance plan.

So what does this look like? A well-rounded plan for shoulder health involves general mobility, upper body strength, and efficiently using oxygen for muscle force production, also known as your aerobic capacity. Adaptive rock climbing may not be as fast paced as something like wheelchair rugby, but it can still be easy to get swept away by the activity and put more load on your shoulders than they can handle. Regularly training the shoulders can prepare us for these exciting moments, provide a strong foundation for long-term participation in climbing, and support your participation in functional daily activities.

Exercise Considerations for SCI

People with SCIs are far less likely to get the recommended amount of activity on a weekly basis. This increases risk of diseases associated with sedentary conditions, like cardiovascular disease. But it doesn’t have to be this way! There are many amazing adaptive recreation communities and physical rehabilitation teams designed to help you participate in engaging sports. Rock climbing can be tailored well to meet your individual needs, increase cardiorespiratory fitness, and has been found to have a therapeutic effect towards decreasing depression and anxiety. Together these aspects work to increase physical and mental health and improve overall quality of life in accessible ways.

There are a lot of considerations to make for someone with an SCI when it comes to exercise. Treat this article as a starting point. It can help inform you and you should also consult your physical therapist for more information. With having an SCI, you are more likely to have low blood pressure and need to monitor this during exercise. This occurs because it is more difficult to get blood from the legs back to the heart. Since blood pressure management is so important following SCI, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends specialized clothing or altering body position to create a lower body positive pressure during exercise. The use of compression stockings, abdominal binders, or working out in a recumbent position may be helpful to better regulate the cardiovascular system.

Another thing to be mindful of is the occurrence of autonomic dysreflexia (AD), where the body responds to a perceived noxious stimulus by increasing blood pressure to dangerously high levels. This is often caused by an obstruction in a urinary catheter, but can also be caused by other sources such as physical irritation of clothing or braces. Emptying bowels and bladder or a urinary bag prior to exercise is one of the best prevention methods for avoiding AD. In the event of autonomic dysreflexia, sit upright immediately, stop exercise, and find the source of the adverse stimulus. Call for emergency medical services immediately if symptoms persist.

Your body may have altered feedback in various forms following SCI. Skin protection is another paramount concern while working out, since your body may not be able to feel certain areas of your body little if at all. Frequent pressure relief checks are crucial to staying healthy and protecting your body from future injury. Also keep in mind that pain response may be blunted by medication, so starting conservatively with new exercises and slowly increasing intensity levels is important to prevent causing tissue damage. Check for skin irritation often, start conservatively, and progress slowly. Changes in blood pressure, skin protection, and altered pain response are just some of the ways life with a spinal cord injury can affect exercise.

General Exercise Adaptations and Recommendations

The ACSM Guidelines recommend beginning with a minimum of 2 days per week of aerobic exercise and 2 days per week of resistance exercise, also known as strength training. Stretching should occur daily, especially if you have joint contractures, spasticity, or frequently perform manual wheelchair propulsion or transfers. It is important to establish a motivated rehabilitation team, including a caring physical therapist, before starting an exercise routine following a spinal cord injury.

Aerobic Exercise Recommendations

Performing aerobic exercises is great for your physical fitness. Increasing your activity tolerance will begin to change your body to better support exercises of extended duration like climbing and traveling around your community. Your climbing experiences may translate to improvements for those off-the-wall activities, and vice versa. Training and climbing can support each other! Suggested exercises include rope climbing, especially on longer routes, upper extremity arm bike (arm cycle ergometry), and use of a recumbent elliptical or bike.

- Begin with 5-10 minutes of activity, followed by 5 minutes of active recovery.

- Progress to 20-40 minutes per session.

- Start with moderate intensity: 12/20 Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) on the Borg Scale

- Progress to vigorous intensity: 17/20 RPE

- Aim to decrease rest periods or eliminate them all together, as tolerated through your progression.

Strength Exercise Recommendations

Building strength will allow you to do powerful climbing moves. Off the wall, it can help make functional activities like transfers or getting on and off curbs easier. Strengthening the muscles around the shoulder girdle protects the joint so you can keep your shoulders healthy for a long time. These exercises can be easily performed with materials you have at home. Resistance bands can be tethered in a door frame with a knot closed inside. Dumbbells can be substituted for water bottles and even a can of beans if that is the right challenge point for you. Complete exercises on both sides for exercises that involve movement of a single arm at a time.

- Start with 1-2 sets of 8 repetitions. Find weights that create fatigue or loss of form around this 8th repetition.

- Gradually progress to 3 sets of 10 repetitions.

- Start with moderate intensity 12/20 and progress to 17/20 RPE.

Prone “Ts” – Lie on stomach and lift arms up at 90° while squeezing shoulder blades together. This targets posterior deltoid, rhomboids, and middle trapezius.

Sidelying External Rotation – Lie on side with top arm supported by side and elbow at 90. Draw up the your arm from the ground towards the ceiling use a small weight. It may be helpful to place a small towel roll between your side and elbow. This targets infraspinatus and teres minor.

Low Rows – Hold a tethered band near chest height with straight arms. Keep your torso from moving and pull arms down to side, maintaining a neutral wrist position. This targets latissimus dorsi, rhomboids, and middle and lower trapezius.

Band or Cable Pull Downs – Hold a tethered band with arms overhead. Pull the band down towards your chest leading with the elbows; do not pull behind torso. This targets scapular latissimus dorsi, teres major, and pectoralis muscles.

Seated Diagonal Punch – Hold a tethered band with a straight arm across your body, towards the opposite pant pocket. Keep arm straight and pull band diagonally towards the side of the hand you are using. This “draw your sword” motion incorporates shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation.

Mobility Exercise Recommendations

For mobility, it is most important to prevent contractures and help keep your body balanced. If you spend most of your time flexed in a wheelchair, it is helpful to move in ways that you don’t normally and to stretch the muscles that are working hard for you. The exercises provided focus on stretching your shoulders, torso, and other parts of your upper extremities. All exercises should be performed on both sides of your body. Your legs likely would benefit from stretching as well, but that is beyond the scope of this article.

- Start with 2 times a week on non-consecutive days. Start small and work your way towards daily stretching, if possible.

- Complete static stretches for 10-30 seconds for 2-4 repetitions per exercise.

- You can perform static or dynamic stretches, focusing on areas of tightness. Stretch to the point of feeling of slight discomfort or tightness.

Doorway Stretch – Find a door frame and press your arm into it at 90°, feeling a stretch in the upper front of your chest. Changing the angle of your arm targets different fibers within pectoralis major and minor muscles.

Open Book Stretch – Lying on side with arms extended forward, sweep arm around to opposite side for thoracic rotation. Follow your arm with your gaze.

Seated Side Bending – Reach arm overhead and lean to one side to stretch intercostal muscles.

Seated Back Extension – Lean backwards with your torso. It may be helpful to support your head with your arms in this position. This can also be performed on the stomach by pressing with arms and pushing your torso off the ground. Going against gravity will add a strength component.

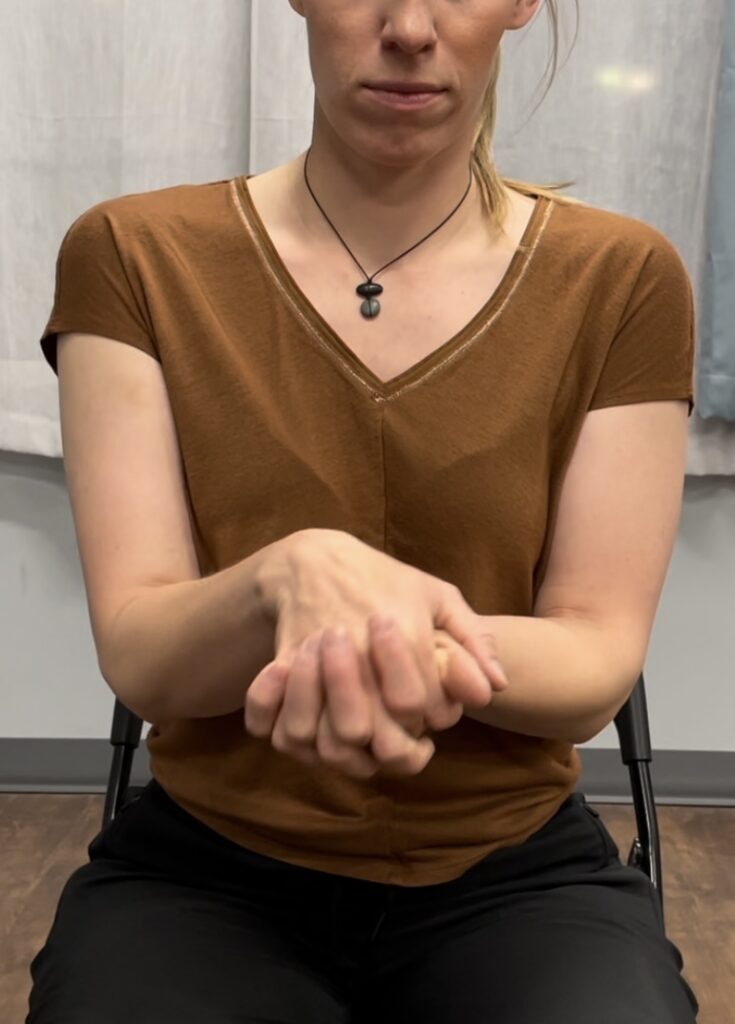

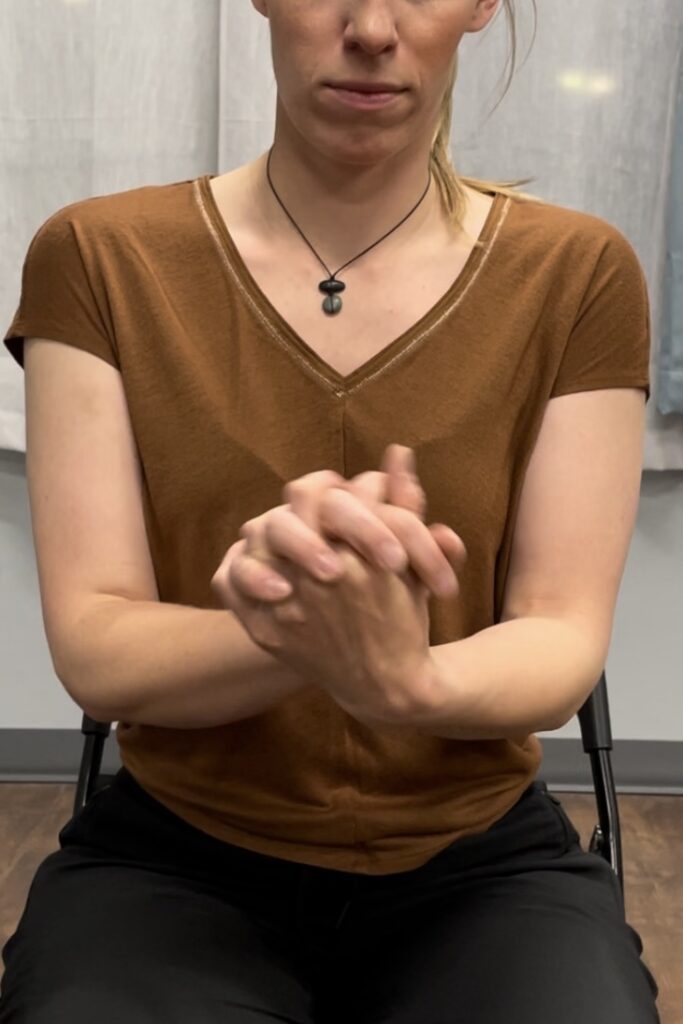

Wrist Mobility – Complete wrist rolls in both directions and stretch into flexion and extension. Show your wrists some love for all the support they’ve been doing during those shoulder exercises and your daily activities!

Activity Modification and Support

Performing activity modifications, in addition to the exercise recommendations above, is vital for decreasing unnecessary stress on your body. With improved body mechanics and techniques during tasks like wheelchair propulsion and transfers, you can save more of that energy for fun activities like rock climbing! While climbing may be your preferred form of exercise, there may be other accessible forms of cross training available for you. For example, pool time can be a great way to supplement your exercise in a supportive environment for you and your joints.

Remember that it’s normal to achieve muscular fatigue quickly, especially if you are just beginning this journey with exercise (again)! A trained professional can help you safely perform exercises and provide education necessary to keep you safe on this journey. Consult your physical therapist and the rest of your health care team before starting any new protocols.

While completing specific physical therapy is important for anyone with a spinal cord injury, there are many amazing organizations around the country supported by paid staff and volunteers to help get you on the wall. The Adaptive Climbing Group and Paradox Sports are just two larger organizations around the U.S. that are prepared to help support your climbing journey. There are many smaller communities local to specific climbing gyms and universities. A trained professional can help connect you to these groups as well as other resources.

Author Bio

Alayna is a Doctor of Physical Therapy Student at the University of Colorado graduating in December 2024. A personal climbing accident changed the course of her life, leading her to choose this second career of physical therapy. Since then she has been able to return to higher levels of function after having bilateral hip surgeries. Alayna is thrilled to help people through injury and other physical challenges to improve quality of life and get people back to the activities they love.

Resources

- Adaptive Climbing Group: https://www.adaptiveclimbinggroup.org/

American Spinal Injury Association Learning Center: https://asia-spinalinjury.org/learning/ - National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability: http://www.nchpad.org/Articles/9/Exercises~and~Fitness

- Paradox Sports: https://www.paradoxsports.org/

- Paralyzed Living Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/c/ParalyzedLiving/featured

- Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence: https://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence

References

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2021.

- DelGrande, Brittany, et al. “Outcomes following an adaptive rock climbing program in a person with an incomplete spinal cord injury: A case report.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, vol. 36, no. 12, 14 Mar. 2019, pp. 1466–1475, https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2019.1587799.

- Hamilton Health Services. “Range of Motion – A Guide for You after Spinal Cord Injury.” California Department of Social Services, 2011, www.cdss.ca.gov/agedblinddisabled/res/VPTC2/8%20Paramedical%20Services/Range_of_Motion.pdf.

- Haubert, Lisa Lighthall, et al. “Shoulder pain prevention program for manual wheelchair users with paraplegia: A randomized clinical trial.” Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, vol. 27, no. 4, 30 June 2021, pp. 40–52, https://doi.org/10.46292/sci20-00013.

- Kaupang, Kristin. “SCI Forum.” Get Moving: Exercise and Spinal Cord Injury, 2013, sci.washington.edu/info/forums/reports/exercise_2013.asp#ability.

- Reinold, Michael M., et al. “Current concepts in the scientific and clinical rationale behind exercises for Glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 39, no. 2, Feb. 2009, pp. 105–117, https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2009.2835.

- Riley, Allison H., and Carrine Callahan. “Shoulder rehabilitation protocol and equipment fit recommendations for the wheelchair sport athlete with Shoulder Pain.” Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, vol. 27, no. 2, June 2019, pp. 67–72, https://doi.org/10.1097/jsa.0000000000000232.

- Vagy, Jared. “Avoiding Overuse Injuries.” The Climbing Doctor, 27 Nov. 2021, theclimbingdoctor.com/portfolio-items/chapter-viii-paraclimbing-avoiding-overuse-injuries/.

- Disclaimer – The content here is designed for information & education purposes only and the content is not intended for medical advice.