The Gym Boulder’s Guide to Preventing Lower Body Injuries While Jumping/Landing/Falling

Are you sending hard only to jump off and twist your ankle and/or knee? Day 1 in the boulder gym we all learn proper falling technique, “gently land with your knees bent and roll to your butt…” but… how many of us actually do that on a regular basis..? Unless you down-climb 100% of the time, most of us are jumping and/or falling 20+ times per gym or outdoor session at distances anywhere from 1-10ft, sometimes greater. Because we don’t live in a perfect world where we all land perfectly every time the following are several strategies and cross training progressions to prevent lower extremity (foot/ankle, knee, and hip) injuries while landing.

Lower Body Injury Risk Factors

Bouldering poses obvious injury risks, especially for the lower body, identifying potential risk factors is often the easiest way to prevent future injury.1,2 Landing safely from a variety of heights planned and/or unplanned requires quick thinking, balance, and coordination. When considering risk factors we must consider environmental factors and individual factors.3

Environmental factors that increase risk of injury during falling/landing include:

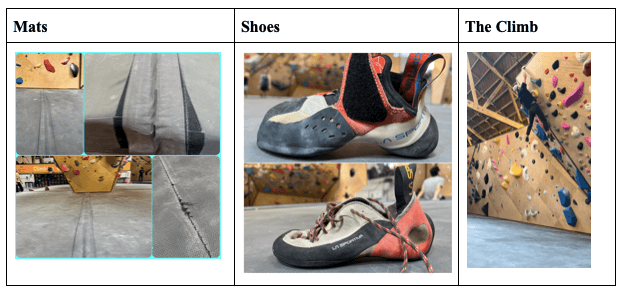

- Mats

- Climbing shoes

- The climb itself

Not only do gym mats require increased time to stabilize the lower extremities upon landing; gym mats come in a variety of different densities, thicknesses, ages, degrees of damage/repairs, and seams which all pose added risks. Additionally, climbing shoes, and the severity of downturn in one’s shoe poses the added risk of landing on the side of the foot and turning the ankle. Furthermore, slick footholds and unexpected falls due to the nature of the holds and setting during a climb increase risk of injury during fall/landing.

Individual factors that increase risk of lower body injury during falling/landing include:

prior history of injury that increases lower extremity instability or genetic hypermobility/instability.4,5

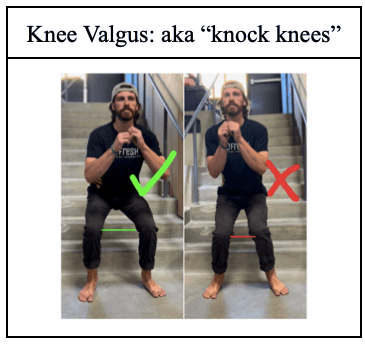

poor coordination or poor neuromuscular control of dynamic stabilization of the lower extremity.4,5

personal choice of landing on feet rather than the shock absorption roll mentioned earlier.

Prior history of foot/ankle, knee, and or hip injury, in general, causes instability of the joint and decreases proprioceptive control during balance activities. Genetic hypermobility/instability of lower extremity may also be present in those with connective tissue dysfunction; such as those with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome or Marfan Syndrome. Poor coordination/neuromuscular control of lower extremities during dynamic stabilization includes increases in knee valgus or “knocked knees” during landing. Lastly, individual factors include personal choice to stick a landing on one’s feet, choice of height at which one is jumping from, and choosing to turn or twist during jump. 70% of ACL injuries are non-contact injuries, meaning they are caused by movement patterns of the individual.6 ACL injuries often occur when the foot is firmly planted and undergoes a sudden change of direction.7 Turning while jumping down inherently increases risk for ACL injury.

Assessment

In order to decrease risk of injury during falling and landing when bouldering one must assess one’s risk factors both environmental and individual. Environmental factors are quick and easy to assess each climbing session.3 Individual factors are slightly more challenging to assess, and for formal assessment/medical diagnoses it is recommended to see a healthcare provider.

Environmental Factors to Assess

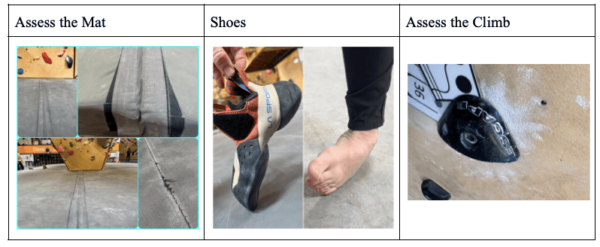

- Assess the mat – Get familiar with the mat: density, thickness, damages, repairs, seams, and mat placement when outdoors.

- Shoes – Notice if your shoes have a severe downturn – putting your ankle in a more turned in position

- Assess the Climb – Look for slick holds, look for the crux/potential falling points, and direction you may fall or land in.

Individual Factors to Assess

1. Prior History of Injury

- Ankle instability: Talar Tilt Following a common ankle sprain, ie. twisting/rolling your ankle the ligaments along the outside of the ankle get over stretched, a quick easy way to assess is by performing a talar tilt test. It is best to compare to the uninvolved side in order to determine if there is increased laxity following an ankle sprain. For confirmation please see an orthopeadic healthcare professional.

- Knee Instability: In order to assess instability in the knee it is highly recommended you are assessed by an orthopeadic healthcare professional.

2. Genetic Hyper Mobility/Instability/Dislocation/Subluxation

- Genetic Hypermobility/Instability is more common than you might think, it may include such diagnoses as Eler’s Danlos Syndrome or Marfan’s Syndrome. However, many people are just genetically predisposed to have increased laxity throughout their joints. Easiest way to identify general hypermobility, look for hyperextension in multiple joints; such as the knee, elbow, and thumb.

- Chronic Dislocations/Subluxations – In more severe cases people with genetic hypermobility disorders will experience chronic dislocations and or subluxations, where the joint “pops out and quickly pops back in.” If this is something you’ve experienced, or is a concern for you, it is recommended to see a healthcare professional for formal diagnosis.

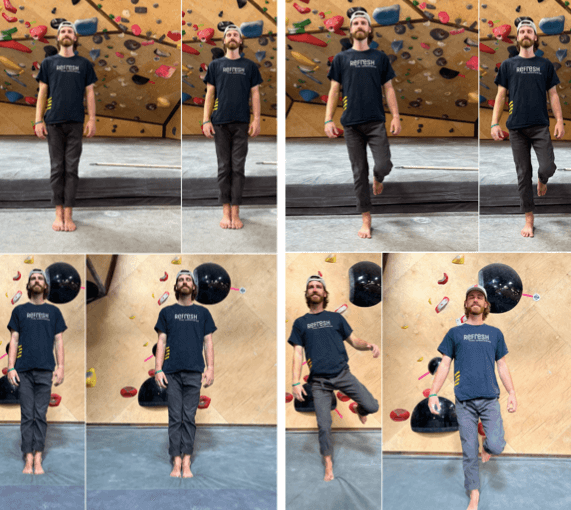

3. Neuromuscular Control (coordination of balance)

- Rhomberg Test: is a quick easy test to examine one’s static balance – otherwise known as balance when not moving. While falling and landing during climbing is a dynamic movement, it is often recommended to achieve proficiency in static balance prior to dynamic balance first with eyes open followed by eyes closed. It is recommended one is able to maintain balance in the different scenarios for 30 seconds.

- Dynamic Balance with Landing Error Scoring System (LESS):<