This article was published in the APTA Magazine – The American Physical Therapy Associations Signature Publication. The full PDF of the article is below for reference in both PDF and text:

Fullscreen ModeDefining Moment: Through the Open Door

A PT’s journey with rock climbing and movement science.

I can still vividly remember hanging by my fingertips from the molding of the doorframe at my grandma’s house to strengthen my fingers for climbing. I was in my early 20s, and I had been climbing for a few years already. I was so immersed in the sport that I trained for it in some way each day. Yes, I was completing my doctorate in physical therapy at the University of Southern California, but my identity was that I was a climber, and climbing was my life.

A week later, it all changed.

I had been climbing for six days straight in a local climbing gym, and my body was exhausted. But when a friend called to see if I wanted to ascend Coarse and Buggy, a classic climbing route in Joshua Tree National Park, I leapt at the offer. We loaded our gear into the car and drove 2 1/2 hours east to the park.

Standing at the base of the climb, I nervously took one last glance up. My body was wrecked from the straight week of training, but raw excitement was driving me. At USC, I studied the effects of stress, strain, and fatigue on bodies. I should have known better than to let motivation get the best of me when my body was depleted.

I tightened my harness, chalked up, and delicately pressed my feet into small edges of rock, making my way along a razor-thin crack. Gripping each hold like my life depended on it — and it did — I slowly made my way up the face of the rock. At the top of the climb, I reached an awkward exit move where I had to pull myself around a small roof to finish the climb.

I looked down and was instantly scared. As my legs began to shake and my elbows started to flare outward, my only thought was whether the rope would hold my fall. I took a deep breath and pulled hard. Pop! Although I somehow stuck the move and made it to the top of the climb, that single motion tore the rotator cuff muscles in my shoulder and a pulley ligament in my finger — sidelining injuries for both climbing and performing manual therapy during my clinical rotations.

These injuries were nine months in healing, and they gave me a unique understanding of a climber patient’s point of view. Would I again be able to grip ropes and wedge my hand into cracks? Would I still be able to curl my fingertips strongly into the slightest feature on the rock face? Would my shoulder have the range of motion needed to confidently reach the next hold? And, finally, could I have prepared my body for the specific stress of that last movement? I eventually recovered completely, but I brought those valuable insights into a patient’s mindset with me.

Fast-forward several years; I was still passionate about climbing, but I was a lot smarter about my training. On the career side, I had graduated from USC, gone through a residency program, and reached a point where I was now confident in treating patients. We saw a lot of athletes in our clinic. A significant number of them were getting better, but there were some cases I just didn’t understand.

Recalling my rock-climbing injury, I knew that these cases had to be related to movement, but I didn’t know how. I needed to learn more. Kaiser Permanente offered a fellowship on movement science, and I thought it might provide the answers I was seeking. I applied.

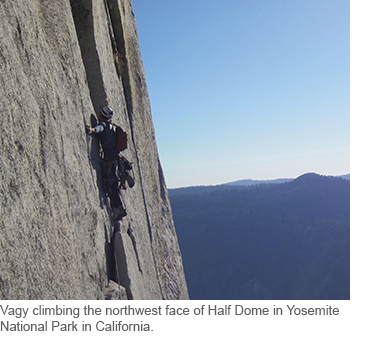

After submitting my application, I made a once-in-a-lifetime choice to pursue climbing full time with the support of two modest corporate sponsorships that provided meals during my expeditions. This was a climber’s dream, and yet I hesitated. My decision seemed simple: Put my career as a physical therapist on hold and pursue my passion for climbing. But should I take the chance? After discussing the importance of this decision with my girlfriend (now my wonderful wife), I was given what has been lifelong advice. She said, “Go through the open door.” If there was an opportunity, I shouldn’t think about it; I should just take it. This idea felt right, and so I quit an amazing job that I had enjoyed for three years, moved out of my beautiful apartment four blocks from the beach, placed my belongings in storage, and traveled to South America.

The time in South America gave me the highest of highs. I completed a technical first ascent — a route on a peak that nobody had climbed. It also brought the lowest of lows — recovering the bodies of two friends who died pursuing their passion for climbing. Words can’t express the emotional roller coaster. I questioned both my desire to continue as a physical therapist and my own mortality.

Yet I continued. Constantly climbing, I didn’t often go online. However, one day before a serious climb, and clearly knowing the risks of such an ascent, I decided to write my family before I headed out. As I quickly scanned my inbox, I saw an email from Kaiser. They were asking me to interview for the movement science fellowship. I had completely forgotten that I applied. Worst of all, since I hadn’t checked my email, the deadline to accept or decline the offer to interview was that very day.

Yet I continued. Constantly climbing, I didn’t often go online. However, one day before a serious climb, and clearly knowing the risks of such an ascent, I decided to write my family before I headed out. As I quickly scanned my inbox, I saw an email from Kaiser. They were asking me to interview for the movement science fellowship. I had completely forgotten that I applied. Worst of all, since I hadn’t checked my email, the deadline to accept or decline the offer to interview was that very day.

I couldn’t decide if I should respond. It was my dream to travel the world and rock climb, but physical therapy was my career. If I was accepted into the fellowship, it would take my complete focus. I couldn’t do both. I had to choose. Should I take the chance? With “go through the open door” echoing in my mind, I accepted the request. One week later, I was headed back to Los Angeles on a same-day roundtrip flight to sit for the interview.

All my clothes were in storage, and I walked into the interview in what I wore on the plane, dressed up with borrowed, too-large dress shoes and a tie. The interviewers asked a series of professional and clinical questions. Since I hadn’t practiced physical therapy in over six months, I felt ill-prepared. I thought there was no way I would get the fellowship position.

Returning to South America after the interview, I was discouraged. It seemed silly to have flown to Los Angeles for a shot at a position I wasn’t likely to get. But I knew that if I hadn’t seized the opportunity for the interview, I would have regretted it.

Over the next few weeks, I anxiously waited for a response. After each climb, I would head back into town, where I had Wi-Fi to check my email. Then it happened. I opened my inbox, and there was a message from the fellowship. I had been accepted.

I was surprised and elated but also a bit at odds. I now had another decision to make. Should I accept and further my career as a physical therapist? Or should I reject the offer and continue my dream of climbing? Once again, “Go through the open door” guided me. I accepted the position.

When I started the movement fellowship, I vividly remember standing in front of one of my mentors, Clare Frank, PT, DPT, MS, and wondering if I was ready. I hadn’t practiced physical therapy for an entire year. Other than basic anatomy, I felt I had forgotten everything I knew. But that ended up being an advantage. At Kaiser, I would learn a different approach to physical therapy.

In the first six months of the fellowship, I was challenged to train my eyes to observe and analyze preferred movement strategies adopted by patients and come up with predictions of impairments. By repeatedly observing human movement and seeing the body respond and compensate, I was shaping my analysis skills. The patients’ conditions that I wasn’t understanding before started to make sense. It didn’t come easy, but I took the same passion I had for climbing and put it into learning the body’s neuromuscular movement system.

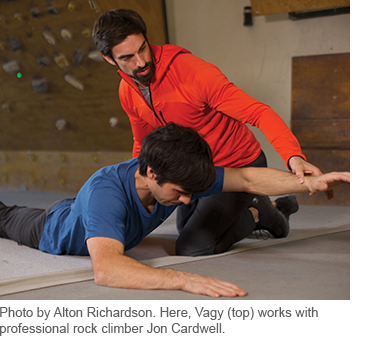

After the fellowship, understanding movement became my obsession. I soon realized that I didn’t have to choose between climbing and physical therapy. I had a unique opportunity to combine the two. Climbing magazines were popular at that time, so I wrote an article. That article turned into a magazine column, and that column turned into an Amazon No. 1 bestselling book, which led to The Climbing Doctor, my physical therapy practice that provides rehabilitation and injury prevention specifically for rock climbers.

Now, over a decade later, I feel fulfilled every day, grateful that I can merge my passion for movement science and climbing. I’ve had the game-changing injury, and I understand the fear it can bring. I understand the body’s movement and know it is the key to learning how to prepare for demands placed upon it. Whether patients are 20, 40, or 60, I encourage them to accept the challenge of working hard to personally make a difference in their recovery and training.

Reaching out for the fellowship was an opportunity. Moving forward with climbing within my career was an opportunity, too. Taking those chances made it possible to successfully combine my passion for climbing and my physical therapy career.

I continue to be grateful. And I continue to go through the open door.

Jared Vagy, PT, DPT, is a board-certified orthopaedic clinical specialist. He is the author of “Climb Injury-Free” as well as numerous articles on injury prevention. He lectures internationally and is a clinical assistant professor of physical therapy at USC.